1.

By the end of her long life, Georgia Totto O’Keeffe, who died in 1986 at the age of ninety-eight, had become one of the most recognized of all American artists, eclipsing even such crowd-pleasing favorites as Norman Rockwell and Andrew Wyeth. During her final years, when macular degeneration had partially blinded her and she painted with the help of an assistant guiding her hand, her popularity was equaled perhaps only by Andy Warhol, who admired her, interviewed her, and borrowed some of her favorite motifs, such as skulls and flowers. Just as Warhol’s varied achievement has coalesced around a few frequently reproduced images—Marilyn, Mao, and cans of Campbell’s Soup—O’Keeffe is best known today for her up-close vaginal flower petals and her austere evocations of a primeval New Mexico.

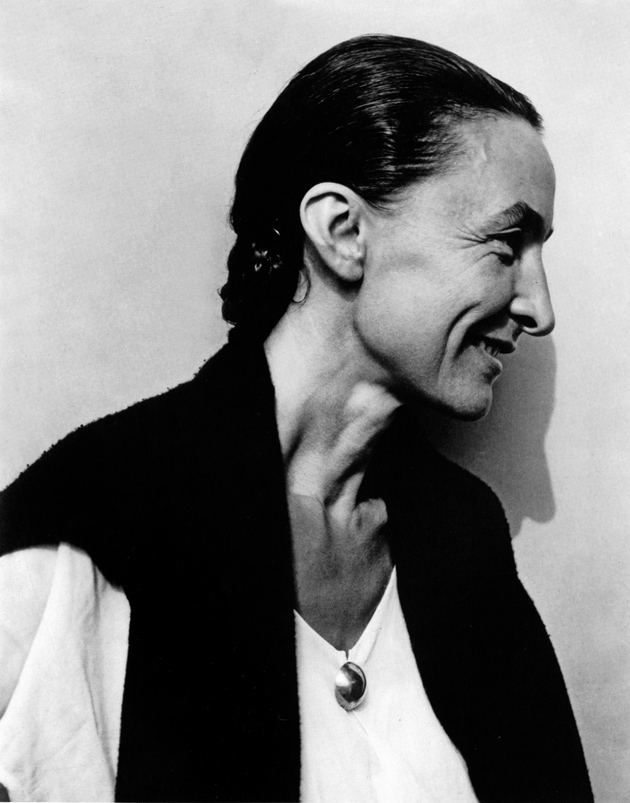

O’Keeffe achieved a strong personal presence as well through the proliferation of photographs of her hard-bitten, heroic face, which seemed to evoke the early pioneers. A cover article in Life magazine in 1968 referred to the “stark visions of a pioneer painter.” Pilgrims visited the remote American Indian village of Abiquiu in northern New Mexico where she had her redoubt, like some desert priestess in voluntary seclusion. During the 1960s and 1970s, she came to stand for a hard-earned and austere integrity. Joni Mitchell, composing the songs of her Ladies of the Canyon album, came to pay her respects, and it was said that Dennis Hopper wrote the script for Easy Rider in the compound in Taos where she had once lived. O’Keeffe seemed as intensely American as Peter Fonda’s Captain America in that film, with Old Glory emblazoned on his leather motorcycle jacket.

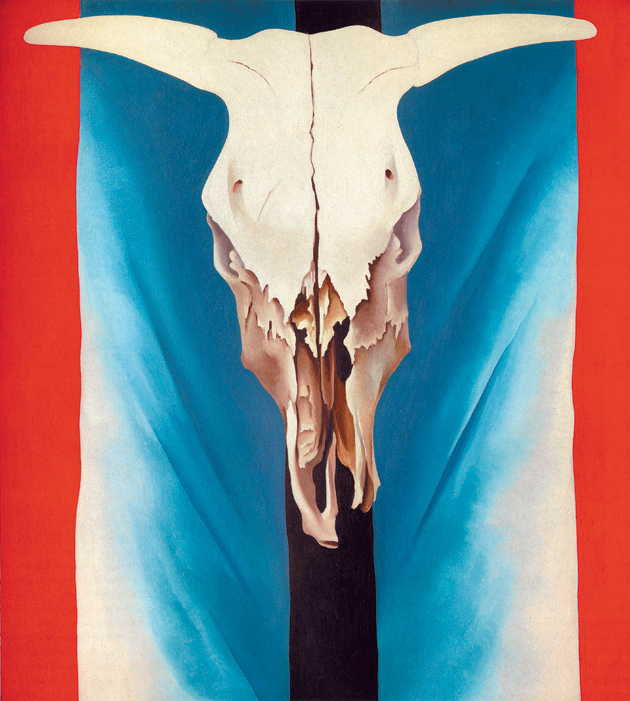

O’Keeffe had playfully worked the national colors into her amazing Cow’s Skull—Red, White and Blue of 1931, reproduced on the Life cover in 1968. The white skull hovers in the foreground, horns outstretched like a crucifix over a pale blue ground, with vertical red stripes on each margin. The blue background seems to be some sort of fabric, perhaps an Indian blanket, painstakingly painted to show the creases—those “shallow, pleated spaces” that the critic Bruce Robertson (in the excellent volume Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction) notes are “uniquely hers.” The red stripes by contrast are applied like house paint, with no illusion of depth; O’Keeffe used a special brush to feather away the ridges of applied paint. She was determined to “make it an American painting,” she said. “They will not think it great with the red stripes down the sides—Red, White and Blue—but they will notice it.”

Knowing how to be noticed was one of O’Keeffe’s most valuable skills as an artist; she knew that mystery was part of her allure. The aloofness she cultivated extended to her personal life, about which biographers have long speculated. At the time of her death in 1986, it was learned the letters she had bequeathed to Yale would remain sealed for twenty years, thus preserving, for a decent interval, any lingering secrets of her personal life. These were thought to concern, in particular, her difficult relationship with the photographer, collector, and art impresario Alfred Stieglitz, whom she married in 1924.

The art historian Sarah Greenough, who has assumed the daunting task of editing O’Keeffe’s correspondence, notes that between their first contact around 1915—when precisely they first met remains uncertain—and Stieglitz’s death in 1946, they exchanged more than 25,000 pages of letters.* The first volume of Greenough’s selection extends only from 1915 to 1933 but fills more than seven hundred pages. More of these letters are reproduced in Katherine Hoffman’s Alfred Stieglitz: A Legacy of Light. The sheer number of letters suggests an interesting paradox: O’Keeffe and Stieglitz seem never to have been closer together than when they were far apart.

2.

Stieglitz, twenty-four years older than O’Keeffe, was born in Hoboken during the final year of the Civil War into a prosperous German Jewish family. After serving as a lieutenant in the Union Army, his father moved the family to Manhattan and made a fortune in the wool trade. Like Henry James’s father, he considered the educational opportunities in America unworthy of his children’s talents and took them to Germany, where young Alfred enrolled in the Technische Hochschule in Berlin. There he developed his lifelong taste for German culture; Faust became his personal touchstone (“It’s better to read Faust—over & over again”), along with Wagner and Nietzsche.

While training to be an engineer, Stieglitz was drawn to technical innovations in photography. He studied with the scientist Hermann Vogel, whose pioneering work in photochemistry, which examines the effect of light on chemical reactions, was crucial to the development of color film. Stieglitz bought a camera and entered photographic competitions before his return to New York in 1890. With friends he had known in Berlin, he joined a firm specializing in photoengraving, and married the sister of one of his partners, Emmeline (Emmy) Obermeyer, a brewery heiress, in 1893.

Advertisement

Stieglitz was temperamentally drawn to difficulty, both in the processes and the subjects of photography. Among his best-known early photographs are Manhattan street scenes under extreme visual conditions. He loved the melancholy of reflections caught in rainy streets at dusk. He is said to have been the first photographer to take pictures during a snowstorm; he experimented with nocturnes and fogs, achieving soft-focus results reminiscent of Whistler and helping to inaugurate, along with his protégé Edward Steichen, what came to be known as Pictorialist photography, with its picturesque subjects and dreamy atmospheric effects. Tirelessly making the case that photography was one of the fine arts, Stieglitz organized clubs, journals, and exhibitions; along the way, he developed a feel for movements, markets, and artistic coteries.

Stieglitz had a talent for selling art, and for persuading collectors that some contemporary artists were better investments than others. A follower of European cultural trends, he took the lead in promoting what came to be known as modern art. His small gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue held the first American exhibitions of Picasso and Matisse, of African art, of children’s art, and of such exotic European tendencies as Dada. An exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Stieglitz and His Artists, and its accompanying catalog, documents the full range of his interests. It was to 291 that Stieglitz’s friend Marcel Duchamp, in 1917, dragged his famous Fountain, a porcelain urinal rejected from an exhibition of independent artists. Stieglitz took several photographs of the “readymade” sculpture, signed R. Mutt, a pun suggesting both the German word for poverty and a mongrel version of art. “The Urinal photograph is really quite a wonder,” Stieglitz observed. “It has an oriental look about it—a cross between a Buddha & a veiled woman.”

The enormous Armory Show of 1913, which introduced advanced European art to many baffled Americans, rendered Stieglitz’s small gallery space less distinctive. Increasingly over the following decades he turned his attention to a few specifically American artists doing original work, and, in support of such an emphasis, called a later gallery An American Place. Foremost among these artists was Georgia O’Keeffe.

3.

O’Keeffe joked that she came from the “tale end of the earth”; the charmingly misspelled word suggests that there was something legendary, like a fairy tale, about her upbringing, which had nothing of Stieglitz’s cosmopolitan urbanity. She always felt like a transplant in New York, exiled from the great open spaces of the West. “That was my country,” she told Stieglitz. “Terrible winds and a wonderful emptiness.”

She was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, in 1887, to a family struggling with a failing dairy farm. Drawn to art early on, she attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for a year before moving to New York in 1907 to study painting at the Art Students League with the fashionable American Impressionist William Merritt Chase. The following year, she saw a very different kind of art when she wandered into 291 and encountered drawings by Rodin and, perhaps, some paintings by Matisse.

O’Keeffe, with no other source of income, supported herself by working in advertising in Chicago, learning to churn out expert drawings in an art nouveau style of elegant curlicues and sophisticated eroticism reminiscent of Aubrey Beardsley. A turning point came when she took a course in drawing during the summer of 1912 at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where her family had moved. Her young teacher, Alon Bement, was a partisan in a national movement to change how art was taught in American schools. The roots of the movement were in the practice of Japanese artists, as interpreted by the maverick philosopher Ernest Fenollosa.

After working for many years in the Ministry of Education in Tokyo, Fenollosa had come to believe that Japanese artists were less interested in providing an accurate representation of everyday life than in constructing abstract decorative schemes based on the division of space and the juxtaposition of color. Art, in Fenollosa’s view, was less concerned with copying reality than with expressing the artist’s moods. Further refinement of his ideas came from the artist Arthur Wesley Dow, who taught at the Teachers College of Columbia University. At Bement’s urging, O’Keeffe returned to New York to work with Dow, whose own art—simplified forms of rural hills and barns—she found “disgustingly tame.” Back in Charlottesville in the summer of 1915, she was determined to produce something bold and unmistakable. The person she most wished to impress, as she confided to her fellow art student Anita Pollitzer, was Alfred Stieglitz, whom she hoped might “like something—anything I had done.”

Advertisement

4.

On New Year’s Day, 1916, Pollitzer brought a sheaf of charcoal drawings to 291. The drawings were radically abstract. Some vaguely suggested art nouveau fountains; others could be taken to be cave interiors or cloud formations on a stormy day. O’Keeffe, a name that meant nothing to Stieglitz, had made the drawings during the previous fall, partly at Pollitzer’s instigation. Pollitzer’s directions, adapted from Bement’s teaching methods, were simple: “Hear Victrola Records, Read Poetry, Think of People, and put your reactions on paper.” After a particularly intense session on Christmas Day, 1915, O’Keeffe wrote Pollitzer, “Did you ever have something to say and feel as if the whole side of the wall wouldn’t be big enough to say it on?”

O’Keeffe was eager to know how Stieglitz might respond to her drawings, perhaps the most radical compositions by an American artist before the experiments of Rothko and Pollock thirty-five years later. “I would like to know if you want to tell me,” she wrote. “I make them—just to express myself—things I feel and want to say—havent words for.” Several myths, probably apocryphal, surround the opening moves of their relationship. Did Stieglitz really exclaim, “At last a woman on paper!”? Did she storm into his gallery a few weeks later, when her drawings were already on display, and announce that she was “Miss O’Keeffe”?

Stieglitz was undoubtedly impressed by her work. He was also intensely interested in her. “Tell me all you will,” he wrote her seductively. “There’s nothing I can not understand and feel. You yearn for some one to understand every heartbeat of yours….” An intense correspondence ensued, as O’Keeffe, short of money as usual, took a teaching job in the town of Canyon, Texas, where, as “the most talked of woman on the faculty,” she shocked the citizenry with her simple clothing and her penchant for driving out into the countryside with the local men.

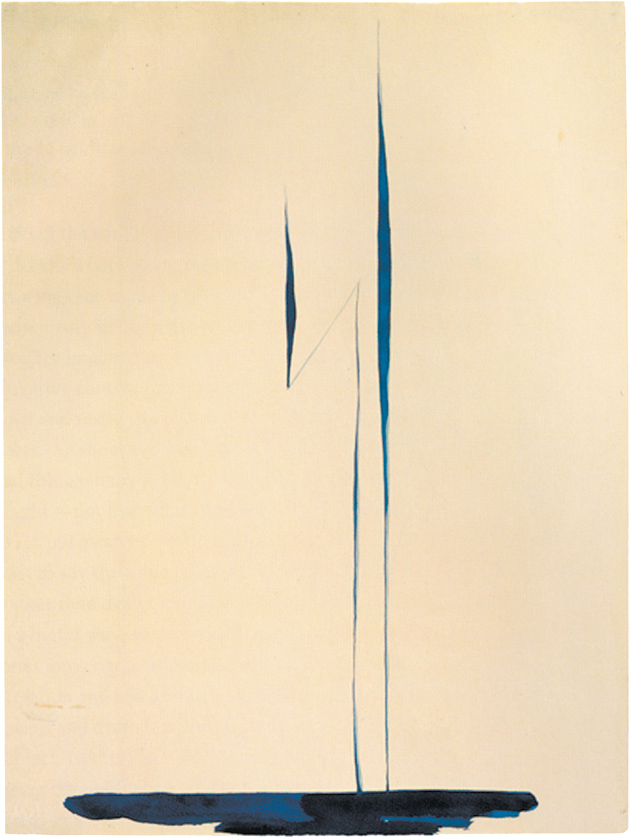

Stieglitz’s pitch that she needed someone older and wiser may have appealed to O’Keeffe, though it seems likely that his influence in artistic circles counted as well. When Stieglitz, encouraged by her increasingly frank letters, urged her to give up her teaching job in Canyon and return to New York, and to him, she readily accepted. When he exhibited her stark Blue Lines X of 1916, two vertical lines, one straight and one bent, in rich blue watercolor, he persuaded himself that the picture represented the two of them. Later, he asked to have the painting cremated with him: “In a way it’s criminal to ask you to have it accompany me beyond all Pain or Ecstasy—but I must take it with me.”

5.

It is tempting to imagine Stieglitz as Pygmalion, with O’Keeffe groomed and marketed until her work sold for sufficiently high prices to make her, according to Barbara Buhler Lynes, “a millionaire in today’s dollars” by 1929. And yet, as one reads the letters and considers the shifting shapes of these complicated careers, one has the impression that it was Stieglitz, past fifty when they first met, who experienced the greater awakening. He felt a renewed sense of purpose in his self-consciously American gallery; at the same time, he rededicated himself to photography, embarking on an ambitious project of photographing cloud formations reminiscent of Constable’s studies. These he named “Equivalents,” suggesting that he was finding sublime metaphors in the sky. On one occasion, he bragged to the poet Hart Crane, with his customary grandiosity, that he had “photographed God.”

In a parallel undertaking, Stieglitz began to compile the series of over three hundred photographic images that comprised his “Portrait of O’Keeffe.” He photographed every part of her body, nude and variously clothed. In one intriguing letter, a meditation on an artist’s relation to her own hands, she tried to make sense of her hand holding one of Stieglitz’s photographs of her hand:

I wondered at my hand—my left one as I saw it on the last printed page of the last book—and my mind wandered to the prints of my hands—I moved to get up to look for them—No—The other hand reached for the book…. So I sat looking at the hand—then at them both—I’ve looked at them often today—they have looked so white and smooth and wonderful—I’ve wondered if they were really mine—

The cloud studies and the portraits intersected when Stieglitz titled a dramatic convolution of clouds, resembling a torso with open legs, Portrait of Georgia.

As Stieglitz’s art moved toward abstraction, in the photographs of clouds and trees at his summer house on Lake George, O’Keeffe’s work moved in the opposite direction. From the radical abstraction of her charcoal drawings, she increasingly painted motifs grounded in the actual world, first flowers, then waves, shells, and other subjects from her visits to the Maine coast. A primary reason for this shift seems to have been her mounting dismay at how her work was interpreted by critics. Prompted by Stieglitz’s public statements about how “the Woman receives the World through her Womb,” gallerygoers were encouraged to find in O’Keeffe’s abstractions imagery of the womb and erotic longing. The artist Marsden Hartley thought he saw in her work “the world of a woman turned inside out” while the critic Paul Rosenfeld wrote, “The organs that differentiate the sex speak.”

O’Keeffe didn’t recognize her intentions in these hothouse responses. She complained bitterly to Sherwood Anderson in 1924:

My work this year is very much on the ground—There will be only two abstract things—or three at the most—all the rest is objective—as objective as I can make it…. I suppose the reason I got down to an effort to be objective is that I didn’t like the interpretations of my other things.

She looked for ways, via titles and explanations, to tether her more abstract work to the real world, asserting some control on how her paintings were understood. She painted flowers in series, where viewers could see increasingly abstract phases of the same subject, as in the remarkable Jack-in-the-Pulpit suite of 1930. Black Abstraction (1927), an unsettling painting of a tiny white pearl of light poised on an oblique angle within black and gray concentric circles was, she explained, based on a memory of coming out of anesthesia.

6.

One might have thought that Stieglitz, with his cosmopolitan education and wide reading, would have produced more absorbing letters, but the reader is confronted on almost every page with his abstract pomposity. “I wondered what kind of a child you’d bear the world some day!” he writes O’Keeffe, “—The Glory of Dawn & the Glory of the Night—& the Glory of the Noon Sun—all combined—within that Womb of Yours.” He complains incessantly about the lousy commercial paper he’s forced to work with and the mediocre film. Laments about his declining health, his aging, and his inadequate medications are eased by momentary sexual distraction. A reader of D.H. Lawrence, he affectionately refers to O’Keeffe’s vagina as Lady Fluffy.

O’Keeffe’s letters, by contrast, are alert to the physical world, to the power of words, and to punctuation. Pages of manuscript reproduced in these books reveal that her dashes, like Emily Dickinson’s, assume all sorts of shapes, from squiggles to playful curlicues to abrupt downward slopes. These expressive dashes recall her charcoal drawings. Often, a passage in the letters will strike one as having a visual analogy to her paintings. She describes, for example, the experience of holding a piece of ritual jade in her hand during a visit to the Asian collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1922. Here we can see her instinctual resistance to interpretation yielding to what she feels is an appropriate chain of associations prompted by a suggestive object:

I handled pieces of Jade—They told me it was Jade—I would not have thought what it might be—I only knew that the surfaces were fine and smooth and cold…the pleasure in the thing its self is some what dulled when you begin to wonder how that particular shape can symbolize the earth and that idea seems to take away from the pleasure one feels—just in the thing its self—So—looking up—a row of round shapes catches ones eye—round—flat—and a round hole in the center—the circle serves to fascinate—you take it in your hand…you are told that these symbolize heaven—that idea does not disturb—for the sun seems round—if you have ever stood on the prairie at night—alone and put your head way back till you look straight up so that you half way see all the horizon at once—a circle unbroken by trees or hills or houses—the heavens seem a marvelously round trembling living thing—you would like to go deep into the colors of these round shapes and be lost….

7.

Two departures punctuated O’Keeffe’s life with Stieglitz. She left the Southwest in 1918, accepting his financial support to free her from teaching, and began living with him after he separated from his wife. In 1929, she returned to the Southwest for an extended stay in part to get away from him. One might think that their ten years together followed a scenario from Ibsen’s A Doll’s House: the patriarchal husband who stifles his wife’s self-development. But this isn’t quite the story that the letters reveal. Stieglitz was many things to O’Keeffe: teacher, financial supporter, promoter, lover, artistic collaborator. She served in return as the stand-out American artist of his circle, but also as his mistress and nurse. The nursing seems to have particularly grated on her. She told Sherwood Anderson that Stieglitz was “just a heap of misery—sleepless—with eyes—ears—nose—arm—feet—ankles—intestines—all taking their turn at deviling him.”

She soon realized that their open marriage meant different things to the two of them. “The difference in us,” she wrote from New Mexico in 1934, “is that when I felt myself attracted to some one else I realized I must make a choice—and I made it in your favor…. You seemed to feel there was no need to make a choice.” While she enjoyed the admiration of independent men like Tony Lujan, an American Indian married to Mabel Dodge, and the mountain men she encountered while hiking in the high country of Colorado, Stieglitz had a taste for young women in vulnerable positions: the family cook, for example, and the young daughters of friends who posed for his camera. As tensions mounted with O’Keeffe, he began a serious relationship with a younger woman, the poet and photographer Dorothy Norman. In February 1932, he exhibited photographs of Norman nude, as though announcing their affair. “I feel like a battlefield terribly torn and dug up,” O’Keeffe wrote.

It’s easy to blame Stieglitz for being, at best, an indifferent husband. He made little effort to defend his behavior. But his candidness made it easier for O’Keeffe to strike out on her own. In this sense, he freed her, however painfully and cruelly. “I am very grateful to you for all of it,” she wrote in 1929, adding that her experience with him made it “very difficult” for people “to touch any place in me that hurts.” He had taken her heart, she told him, “and at the same time left it for me in a usable form.” Out West, where Stieglitz tactfully never followed her, O’Keeffe learned to drive the motorcars he hated. She achieved what the art historian Anne Middleton Wagner calls her “purposeful reinvention as O’Keeffe the resolute desert elder, an apparently indomitable character who has moved beyond the mere trivialities of age and sex.”

O’Keeffe’s letters from New Mexico are exultant. She explored the canyons and arroyos, learning what she could, under Lujan’s guidance, of the native people. Her great paintings of skulls and other desert detritus—“bones and rocks and sticks and flowers and feathers”—date from these years. She was bringing dead things to life, both herself and the objects that came her way. Her skulls are not memento mori but resurrections. Instead of painting the skyscrapers of New York as though they were pueblo cliff-dwellings or giant kachina dolls, as she had during the 1920s, she painted the real thing. If there was an element of kitsch in some of these pictures, it was a risk she was willing to run. O’Keeffe recalls the heroines of Willa Cather’s novels, with their openness to the sublime experiences of the West.

One can see Stieglitz’s sharply diminishing place in her life—as she herself might have memorialized it in one of her abstract paintings—in a remarkable letter from the summer of 1928, as the train she is on pulls out of the station in Lake George where they had shared a house, and Stieglitz is left behind:

A little black triangle made by your cape—disappearing into the white triangle of the station pillars—then your black triangle again disappearing into the darker black shape of the station door—your head just a tiny white dot at the top of your own black triangle—your hand a moving waving thing—the disjointed part of the straight shapes—

Then we went around the bend and you were gone—

This Issue

January 12, 2012

Do the Classics Have a Future?

Convenience

Republicans for Revolution

-

*

Greenough writes that “O’Keeffe and Stieglitz first met in the spring of 1916,” but two pages later says they “met in 1915.” Lisa Mintz Messinger, in Stieglitz and His Artists, writes of “their first face-to-face meeting, in 1917.” ↩