The preconceived notion might be that Balzac was a gourmand, a modern-day Gargantua, excessive in his feasting as in his writing and his socializing and his consumption of coffee and his pursuit of titled women. Just look at Rodin’s nude study of him, with his Jovian girth and prominent belly. That’s the image most of us have of Balzac—and it seems it was fairly accurate since Rodin, some forty years after Balzac’s death, had his old tailor make to measure a set of his clothes so that the sculptor could have an exact sense of the writer’s body. Not only do we imagine that Balzac ate to excess. We also expect his Parisians to be gorging themselves indiscriminately on all the rich foods of the world, prizing fruits out of season and grating truffles over everything and downing hundreds of oysters.

But it’s a very different picture that Anka Muhlstein presents, one that is more nuanced and contradictory and surprising. Most of the Parisian women of fashion in Balzac’s era (and books) are on diets. Only the Princesse de Cadignan understands that to attract her lover, who loathes affectation, she should eat heartily. As Balzac tells us, “In Paris people eat [half-heartedly] and trifle with their pleasure.” No one ever comments on the food, which is assumed to be uniformly excellent.

It’s still that way. I can remember when I first moved to Paris how dismayed I was that no one ever praised my carefully prepared meals except when I offered seconds; then they turned down another helping but murmured that it was all very good. It took a while to learn that the fiction, at least in the past, was that everyone had a famous chef in the kitchen and it was pointless, even a bit insulting, to compliment the host or hostess on the food. One flustered woman even said to me, when I assured her that everything was excellent, “Don’t look at me—I didn’t cook it!” Muhlstein tells us: “In society, people do not go out to enjoy a delicious meal but to do business, to conspire, to hear the latest news, and to make sure they are seen.”

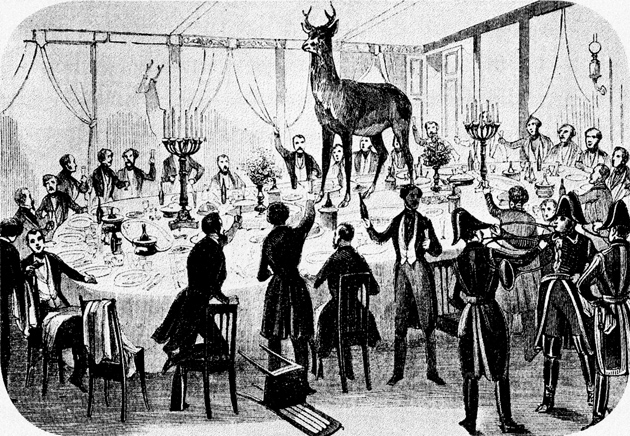

Another thing that hasn’t changed in nearly two hundred years: the French, then as now, dislike the smell of cooking and esteem the visual presentation of food above its taste. Whereas we think it’s cozy and welcoming and mouth-watering, they find the odor of warmed food revolting. James Rothschild, the founder of the French branch of the banking family, was so determined that cooking odors would not disturb his guests that he had the kitchen situated far from the château and the food delivered by a little underground railroad. His chef was Carême, the most famous culinary genius of the day, who specialized in pièces montées—complex architectural table decorations that represented castles or parks and presented lobsters holding up a statue of Diana, say, or cream puffs stuffed with fruit and placed as cannons on a royal barge. Though these creations contained food, they were not meant to be eaten. Carême, who’d studied to be an architect, said that pastry was the highest form of architecture.

To get a good meal, in Balzac’s world, the characters must go to the provinces. There they may not have the same choice of luxurious foods but the ingredients, at least, will be fresh. In this way Balzac was a bit like us: he prized fresh food served simply. He didn’t like elaborate sauces. For him a simple dish of haricots verts could be the acme of a healthy meal, whereas a later chef, Escoffier, thought the glory of French cuisine was that no ingredients were recognizable after they’d been prepared and cooked. Muhlstein defines Balzac’s culinary ideal as natural ingredients with no spices added whatever.

Balzac, we learn from Muhlstein, didn’t know any celebrated chefs and therefore had no inside information about their métier. He never observed a great chef at work. He describes the actual procedures of only one cook, the aunt of Vautrin, and she mixes poison into dishes intended for her nephew’s enemies. Balzac, who loved to study techniques, crafts, and arts and could describe them at length in his novels, actually knew very little about cooking. He ate abstemiously when he was writing for fear of overworking his digestion, “to avoid wearying the brain,” as he put it. During his intense, prolonged bouts of composition all night long and well into the day he drank only water and coffee and ate nothing but fruit. Muhlstein adds:

Occasionally he took a boiled egg at about nine o’clock in the morning or sardines mashed with butter if he was hungry; then a chicken wing or a slice of roast lamb in the evening, and he ended his meal with a cup or two of excellent black coffee without sugar.

His death has been attributed to caffeine poisoning. Certainly he took coffee seriously and spent much effort looking around Paris for the three different beans he needed for his special blend. And he no longer boiled coffee as they did in the provinces; he had an elaborate filter pot to prepare it. Tea was so rare that it could be obtained only at the pharmacist’s.

Advertisement

If Balzac was abstemious while writing, once he’d completed a book and the proofs were sent off to the printer,

he sped to a restaurant, downed a hundred oysters as a starter, washing them down with four bottles of white wine, then ordered the rest of the meal: twelve salt meadow lamb cutlets with no sauce, a duckling with turnips, a brace of roast partridge, a Normandy sole, not to mention extravagances like dessert and special fruit such as Comice pears, which he ate by the dozen. Once sated, he usually sent the bill to his publishers.

Parisians were obsessed with oysters; six million dozen were consumed a year. Pears had a special appeal for Balzac; he often kept bushels of them at home and could eat as many as forty or fifty in a day (one February he had 1,500 pears in his cellar). In any event, perfect fruits in a wide variety and even off-season were available only in Paris. As a young man Balzac was so poor and abstemious that he was very thin; only later did his binge eating result in his big stomach.

Balzac was one of the first novelists to establish character through descriptions of meals. (We don’t know what the Princesse de Clèves ate or when, nor is the dreadful couple in Les Liasons Dangereuses ever shown at table.) Balzac seldom mentioned actual dishes or recipes; rather he described the table settings, the freshness of the ingredients, the conversations, the number and variety of the foods on display. With disgust he often reported the effects of drunken excess, the mindless swilling of expensive vintages, the wholesale destruction of the beautifully arranged servings of food. The visual aspect of the table and sideboard counted more for him (and most of his contemporaries) than the actual taste. A dirty glass or napkin was enough to dull his appetite. Eating for its own sake did not interest him and he preferred gnawing on an apple to sitting down to a banal dinner.

In Père Goriot he renders in sickening detail the boardinghouse meal Madame Vauquer feeds eighteen lodgers for thirty francs a month each. Extras cost more—a drop of eau-de-vie in the after-dinner coffee, pickles and anchovies during the meal. There is no tablecloth and the napkins are changed only once a week. The favorite main course is boned mutton served with turnips and carrots. Her biscuits are laced with mold, though the wines can be surprisingly good. The conversation is primitive and raucous, even disgustingly empty and repetitious. When Rastignac comes back from a lunch with his rich, titled cousin he is severely depressed by the sight of his fellow lodgers at table “about to feed like cattle in their stalls….”

Balzac had little sympathy for gourmands and overeaters, a sin he compares to an excessive longing for women. He believed that overindulgence of any sort would shorten one’s life (he himself was only fifty-one when he died). He compared lust and greed often and saw them as the two main ways that rich men lose their fortunes. If overindulgence is one sin, miserliness is an equally grave fault. Neither excess leads to happiness.

Balzac’s misers are some of his best characters. Monsieur Hochon is reading his daughter’s marriage contract when his cook asks him for some string to truss the turkey. He takes an old shoelace from his pocket and tells her, “Give it back.” Monsieur and Madame Sauviat in The Country Parson are so stingy they never buy meat except on holidays. Ordinarily they make do with herrings, hard-boiled eggs, and cheese. Cheese itself until the middle of the nineteenth century was considered food fit only for the poor. Walnuts were also despised as paupers’ fare.

Grandet in Eugénie Grandet has a secret room where he counts his gold and calculates his next financial move. He terrorizes his wife and daughter and keeps them in extreme penury. His nephew, a Paris dandy, comes to visit, not knowing that his father is ruined and that he must live here in Saumur in the provinces from now on. On the first morning of his stay the old servant woman asks the master for some butter and flour so that she can make their guest a tea cake and the old miser exclaims, “Do you want the house to be turned upside down for my nephew’s sake? Is my nephew to eat me out of house and home?”

Advertisement

When Nanon, the maid, decides that she must go to the butcher in order to make a good broth for the nephew (these broths or “meat essences” are considered the mainstay of good cooking), Grandet says:

“You’ll do nothing of the kind…. I’ll tell Cornoiller to kill some ravens for me. That’s the game that makes the best broth on earth.”

“Is it true, sir, that they feed on dead things?”

“You’re a fool, Nanon! Like every other creature they live on what they can pick up. Don’t we all live on the dead? Where else do legacies come from?”

We can easily imagine Balzac grinning fiendishly at the grotesqueness of this dialogue.

If Grandet is quick to sell every valuable thing he gets his hands on, another miser, Gobseck, hoards food until it rots. These men take only an abstract pleasure in their hoarding—and they use their miserliness to torture their families and servants, who are often unaccountably loyal and kind. When a stranger enters Gobseck’s storage room, Muhlstein tells us, he finds “a huge quantity of eatables of all kinds—putrid pies, mouldy fish, nay, even shell-fish, the stench almost choked me. Maggots and insects swarmed.” When Madame Hochon wants to honor her guests by offering them fruit, the servant replies, “But, madam, there is no rotten fruit left.”

Byron once said that a woman should never be seen eating anything but lobster salad and drinking champagne. Balzac certainly would agree on the champagne part, though one of the fascinating bits of information that this book provides is that champagne wasn’t truly popular until after 1830, since before then the bottles often exploded, as many as 30 to 40 percent of them in any given year’s yield. After that the vintners developed a reliable technique for measuring the bottle’s sugar content and found ways to avoid explosions. In the same way fresh fish wasn’t easily available in Paris until the middle of the nineteenth century when railways between the city and the coast were constructed.

Muhlstein also gives us a quick summary of the rise of the restaurant—an event that happened in France during the Revolution and made Paris the culinary capital of the world. Until then inns had served badly prepared meals with little to choose from at a long table d’hôte. Now some of the chefs from the great aristocratic houses, suddenly finding themselves without a job, opened restaurants that offered many dishes; in fact, the menus were sometimes astonishingly long and the prices accordingly high. The chef for the Prince de Condé, as soon as his patron went into exile, opened a restaurant, as did the chef for the king’s brother. There were many nouveaux riches but they were all afraid to live ostentatiously during the Revolution; better to receive guests at a restaurant than to construct an enviable train de vie in a private town house. By 1802 there were some two thousand restaurants in Paris. These places offered a wide variety of dishes and the luxury of private dining rooms where women of quality could be received discreetly and where tricky business or political deals could be worked out in confidence.

Some of the restaurants were so costly that the customers visibly blanched when they received the bill. Others were suited to every pocket—including that of students. As Muhlstein points out, many of the students, even in cheap restaurants such as the one named Flicoteaux, were eating better than they ever did in their provincial homes. At the other end of the spectrum was Véry, the best restaurant in Paris, in the same space in the Palais Royal where Le Grand Véfour, the temple of gastronomy, is located today.

Was Balzac bulimic? Balzac’s Omelette (which was originally titled in French “Waiter, a Hundred Oysters, Balzac and the Table”) is a charming and modest little book that rigorously avoids the big psychoanalytic questions. But there’s plenty of evidence presented here that Balzac felt deeply neglected as a child; he was sent off to a boarding school and not allowed to see his parents for eight years! During that time his cold mother never sent him sweet or savory tidbits to supplement the school’s dreary diet or any pocket money. In the opening pages of his novel The Lily of the Valley he explores his suffering and deep feelings of rejection. Whereas the other boys are consuming rillons and rilletes from home, Balzac has nothing to enjoy. No wonder that in later life two of his mistresses were of his mother’s age. These women, who indulged him, also told him all the gossip of the past and present, which supplied the hard-working novelist with elements of his plots.

Again in The Lily of the Valley there is a remarkable letter from an older, married woman named Natalie to the young first-person narrator, Felix, telling him that the best sort of mistress to have is an older woman. She tells him that once someone enters society one must obey its rules. People who talk about themselves are avoided whereas those who draw others out are cherished. She urges Felix not to fall into the error of youth, to rush to harsh judgments of other people. Finally she states:

Your springtime is short, endeavor to make the most of it. Cultivate influential women. Influential women are old women; they will teach you the intermarriages and the secrets of all the families of the great world; they will show you the cross-roads which will bring you soonest to your goal…. The woman of fifty will do all for you, the woman of twenty will do nothing….

It somehow seems significant that Balzac slaved night and day to write The Human Comedy so that he could afford to marry a gentle, kind, middle-aged noblewoman—and that he died five months after the wedding. This titan of literature remained a hungry little boy till the day of his early death.

This Issue

January 12, 2012

Do the Classics Have a Future?

Convenience

Republicans for Revolution