Although it left in its wake a number of excellent books, the fourth centennial of the publication of the King James Bible, or KJB, came and went without any of the high-profile public readings and fanfare that marked the three-hundredth anniversary in 1911. A substantial majority of Americans may still “believe in God,” yet the book that found its way to America in the seventeenth century and helped engender on this continent what Lincoln called a “new nation” is rapidly becoming terra incognita. Whether in the King James Version or in newer versions, the Bible is neither read, nor read aloud, nor memorized to anywhere near the extent it was when Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson extolled the KJB as America’s “national book” a century ago. It is anyone’s guess whether a century from now the fifth centennial of the King James Bible—a masterpiece of English prose and the most important book in the history of the English language—will be celebrated at all.

What does Western culture lose when it loses its biblical literacy? At the very least it loses a great deal of access to its literature. This is true not only of medieval and Renaissance literature but of a large part of the modern canon as well. How much of Nietzsche is comprehensible without a basic knowledge of scripture? Hardly a chapter in Thus Spoke Zarathustra does not contain overt allusions to or echoes of the Bible. The spiritual depths of writers like Emerson, Thoreau, and Dickinson are largely closed off to those who cannot hear in their inner ear the basso continuo of these New Englanders’ ongoing dialogue with the Bible. The same can be said of any number of modernists—Yeats, Joyce, Stevens, Eliot, and the bleak Samuel Beckett, who constantly engaged, if only to subvert, biblical motifs and paradigms.

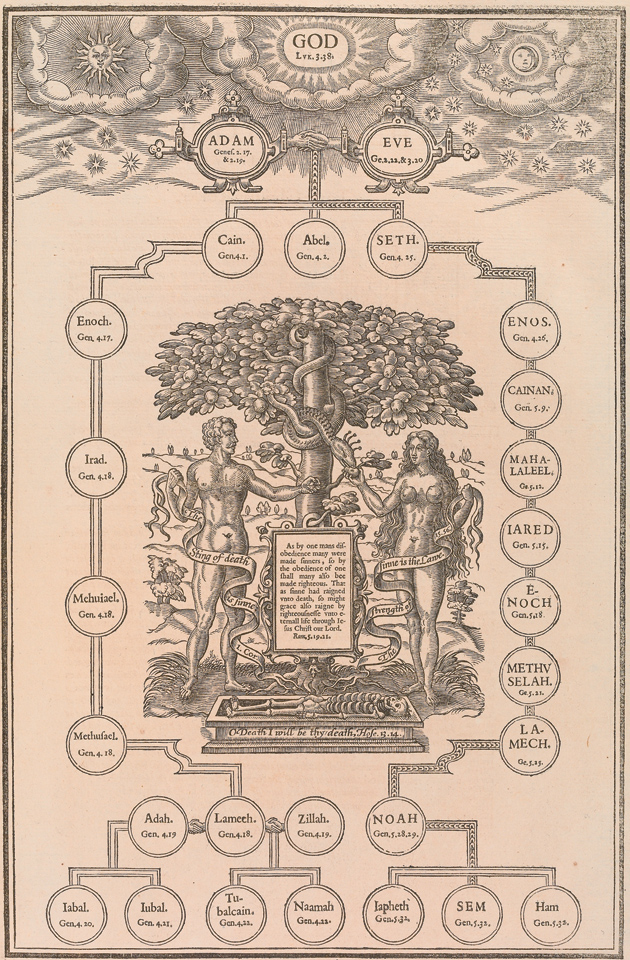

In Pen of Iron, the eminent Bible scholar and translator Robert Alter recounts a small yet telling part of the story of American literature’s attunement to the King James Bible. Exploring the way the KJB has impacted both the prose and worldviews of select American authors—mainly Lincoln, Melville, Faulkner, Hemingway, Bellow, and Cormac McCarthy—Alter shows that, even when they parody it or contend with its legacies (as Melville and Faulkner did), the King James Bible remains an enduring point of reference, if not a moral center of gravity, in their work.

One of the principal claims of Pen of Iron is that style is more than a set of rhetorical and aesthetic qualities; it is “the vehicle of a particular vision of reality.” Thus the style of America’s onetime national book—its diction, tone, cadences, and above all its unique combination of archaic formality and straightforward simplicity, or what Edmund Wilson called “that old tongue, with its clang and its flavor…in its concise solid stamp”—this distinctive style of the King James Bible, which resonates so deeply in Martin Luther King’s most memorable speeches, conveys in its linguistic texture values and sensibilities that have permeated America’s sense of its moral and spiritual identity.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address became part of America’s sacred scripture because the sonority of its words, the dignity of its diction, and the cadences of its sentences reprised and incorporated the rhythms and tones of the King James Bible. Lincoln’s deliberately archaic opening phrase—“Four score and seven years ago”—in its echo of the King James Bible’s “three score and ten,” gives a rhetorical weight to the span of time that had elapsed between the Republic’s founding and its Civil War, in a way that “Eighty-seven years ago” could not have conveyed. Likewise his closing phrase, “shall not perish from the earth,” with its echoes of Job, Jeremiah, and Micah, confers on the sacrifice of the soldiers who died at Gettysburg a moral elevation that their cause, in the American psyche of the time, could not have derived from any other source.

The day may indeed come when the King James Bible itself will perish, if not from the earth then from America’s cultural memory, yet meanwhile Alter finds that it continues to resound—albeit in its darkest tones—in a twenty-first-century novel like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. That novel imagines a devastated future earth reminiscent of the Flood or the catastrophes visited upon Job projected onto a collective scale. “Sentence by parallel sentence, word by hard-edged word,” writes Alter, “it draws on the structures and something of the diction of the King James Bible to forge without pathos a reality whose harshness beggars the imagination.” Yet it also draws on those same sources to envision restoration and renewal:

Advertisement

This contemporary imagining of an appalling end-time and what hope might be sustained after the apocalypse is anchored in the language and ideas of the memorable text that was put into resounding English in 1611 and first framed in Hebrew in the Iron Age.

If the Bible remains a gateway to centuries of literary history in the West, the King James Version of 1611 represents something of a literary miracle in its own right. Alter declares that all the subsequent, more “accessible” English translations “happen to be stylistically inferior in virtually all respects.” Coming from someone who has published highly acclaimed new translations of many books of the Hebrew scriptures, most recently The Wisdom Books: Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes (2010), that statement says quite a lot. Its lofty endorsement is shared by Harold Bloom, who, in his most recent book, The Shadow of a Great Rock, offers what its subtitle calls “a literary appreciation of the King James Bible.” Quoting profusely from a great many passages in the 1611 translation, Bloom shows in granular detail why, in his words, “the sublime summit of literature in English still is shared by Shakespeare and the King James Bible.”

If Bloom is right that “a test for great poetry and prose is an aura of inevitability in the phrasing,” then the King James Bible passes that test brilliantly, thanks in part to the way it ends most of its verses with emphatic metrical stresses or resounding words, be they nouns, verbs, pronouns, or other parts of speech. Here are a few samples that I choose more or less at random from Yahweh’s series of rhetorical questions to Job in chapters 38 and 39 of the Book of Job:

Who shut up the sea with doors, when it brake forth, as if it had issued out of the womb? (38:8)

Hast thou commanded the morning since thy days; and caused the dayspring to know his place? (38:12)

Who provideth for the raven his food? when his young ones cry unto God, they wander for lack of meat. (38:41)

Knowest thou the time when the wild goats of the rock bring forth? or canst thou mark when the hinds do calve? (39:1)

Canst thou number the months that they fulfill? or knowest thou the time when they bring forth? (39:2)

Compared to the strong lineaments of verses such as these, most of the poetry written in English today shows precious little “inevitability” in its phrasing. Some of the factors that have contributed to the drastic decline of the art of bringing phrases to closure are clear enough. They include the wholesale de-formalization of poetry in our time and the consequent premium placed on enjambment; our dogmatic insistence on open-endedness and the bland tones of everyday language; our predilection for understatement and uneasiness about rhetorical display; our aversion to affirmation and our cult of the whisper. In England the art of poetry was at its zenith in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and it left its mark throughout the King James Bible.

The KJB’s “cognitive music,” as Bloom calls it, has a lot to do with the English translators’ efforts to provide a “literal” rendition of the Hebrew scriptures. As Gerald Hammond put it in his masterful 1982 study, The Making of the English Bible, the translators struggled to “reshape English so that it could adopt itself to Hebraic idiom.” Robert Alter reaffirms as much when he remarks on “the peculiar and productive decision [of the English translators] to follow the contours of the Hebrew in idiom and often in syntax.” Likewise Bloom speaks of the “gorgeous exfoliation of the Hebrew original,” even if he insists, rather predictably, that the English translators were engaged in an “aesthetic agon” with it.

Bloom sees the agon between the English translators and the authors of the Hebrew Tanakh as a struggle among literary heavyweights. He finds no such contest when it comes to the authors of the New Testament, whom he deems woefully lacking in literary merit. “The Greek New Testament,” Bloom writes, “is mostly composed by people thinking in Aramaic or Hebrew but writing in demotic Greek.” As literary counterparts, these “people” were not in the same league with the highly learned English translators who grappled so mightily—and successfully—with the sublime Tanakh. “For the most part,” writes Bloom about the King James Version of the New Testament, “the translation is an immense improvement” over the original.

Even if that is true, Bloom’s claim remains extremely questionable when it comes to texts like the Epistles of Paul, if only because Paul aggressively sought to overturn the hierarchical standards that exalt the sublime over the simple, the wise over the foolish, and the noble over the humble. The following passage from 1 Corinthians makes clear what is at stake for Paul in his attempt to bring about what Nietzsche would later call a Christian “transvaluation of values”:

Advertisement

For Christ sent me not to baptize, but to preach the gospel: not with wisdom of words, lest the cross of Christ should be made of none effect.

For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God.

For it is written, I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and will bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent.

Where is the wise? where is the scribe? where is the disputer of this world? hath not God made foolish the wisdom of this world?

For after that in the wisdom of God the world by wisdom knew not God, it pleased God by the foolishness of preaching to save them that believe. (1:17–21)

Paul may be more eloquent in the words of his English Renaissance translators than he is in his own “demotic Greek,” yet this apology for holy foolishness is no foolish piece of rhetoric. It is a highly crafted use of figurative language that turns the cross into an agent of contradiction. In Paul’s proclamation, “this world” is a topsy-turvy one that the Christ event has turned upside down (from his Christian perspective, that means right side up). Such is the “effect” of the cross—it converts the entire order of things, so that high now becomes low, wisdom becomes foolish, and foolishness becomes wise.

I draw attention to this passage in 1 Corinthians because it articulates a Christian inversion of values that had much to do with the translation of the Bible into English during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. To see why this is so, we must revisit the story that many of the books under review here retell from a variety of perspectives—namely, the genesis of the King James Bible.

If there was a genius behind the King James Bible, it was the English priest William Tyndale. Shortly after he was ordained in 1521, he resolved to translate the Bible, despite opposition from both the English clergy and monarchy, which at the time did not support English translations of the Bible. In a verbal dispute with a clergyman who had objected to him, “We had better be without God’s laws than the Pope’s,” Tyndale reportedly answered: “I defy the Pope and all his laws; and if God spare my life ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough, shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.” In the minds of English reformers like Tyndale, the drive to make the Bible accessible to the plough boy and thereby dispossess the clergy of its traditional authority over scripture was consistent with Paul’s exaltation of foolishness over the presumption of the “scribes” and the wisdom of “disputers.” It was the reformist doctrine of “the priesthood of all believers” that mandated vernacular translations of the Bible.

Before Tyndale was burned at the stake as a heretic in 1536, he managed to translate the entire New Testament and roughly half of the Christian Bible’s Hebrew scriptures into English. There had been earlier English versions of the Christian Bible, yet Tyndale—an extraordinary linguist with a remarkable literary ear—was the first to base his translations on the Greek and Hebrew texts. His translation of the Greek New Testament, which had been made available by Erasmus in 1516, became the first edition of its kind in English. Printed in Worms in 1526, it was condemned that same year by Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall and banned by royal proclamation in 1530. Nevertheless, it had considerable diffusion and popularity in England. (Those interested in the fascinating convergence of translation from the original Greek and Hebrew texts, the rapidly advancing biblical scholarship of the time, and the expansion of print technology will profit greatly from reading the two exhibition catalogs under review, Manifold Greatness and Under Eagle’s Wings, as well as the excellent books by Timothy Beal and Gordon Campbell.)

Tyndale, who fled from England to the Continent to pursue his translation project, provoked the ire of important figures like Bishop Tunstall, Cardinal Wolsey, and Sir Thomas More, the latter writing a two-thousand-page “confutation” of Tyndale’s response to More’s Dialogue Concerning Heresies. More objected to, among other things, Tyndale’s translation of the Greek ecclesia with the word “congregation” rather than “church,” as well as to his use of the word “senior” instead of “priest” and “love” instead of “charity.” More’s venom notwithstanding (he accused Tyndale of “discharging a filthy foam of blasphemies out of his brutish beastly mouth”), Tyndale’s translations proved so remarkable in their plain English idiom, so resolute in their phrasing, and so sonorous when read aloud that it was impossible to ignore what he had accomplished. Indeed, the Tyndale Bible was incorporated, with various revisions and emendations, into all subsequent English versions up through, and including, the King James Version. “It has been estimated,” writes Gordon Campbell in Bible about the KJV New Testament, “that 83 per cent of the KJV published in 1611 derives from Tyndale, either directly or indirectly through other Bibles.”

Some of those other Bibles played important parts in the lead-up to the 1611 King James Version. After Tyndale was executed, his project was continued by Miles Coverdale, who produced translations of the portions of the Hebrew texts that Tyndale did not live to complete. Coverdale, unlike Tyndale, based himself mostly on new Latin and German translations rather than on the Hebrew original. He changed some of Tyndale’s controversial renderings, yet much of the Coverdale Bible, published in 1535, simply adopted Tyndale’s translations word for word.

A revised edition of the Coverdale Bible appeared in 1537 under another name—the so-called Matthew Bible—and two years later a modified version of the Matthew Bible was published with the authorization of King Henry VIII. Due to its large size (roughly fifteen inches by nine inches), it came to be known as the Great Bible. The Great Bible in its turn was revised and republished in 1568. Because the revision committee was made up largely of bishops, it was called the Bishop’s Bible. The Bishop’s Bible remained the official English translation until the King James Version appeared in 1611.

The most important and beloved English Bible to appear in this period was the unauthorized Geneva Bible, so named because Geneva, in Switzerland—a republic at the time and a stronghold of Calvinism—became the place of refuge for many English Protestants when the Catholic Queen Mary I ascended the throne in 1553. There the biblical scholar William Whittingham, in collaboration with Miles Coverdale and other scholars, oversaw the translation and production of the resolutely Protestant Geneva Bible. Published half a century before the King James Version, this was the version that the early Puritans brought with them to America and the one used by Shakespeare, Milton, Donne, and other literary luminaries. Mass-produced in affordable editions, and much more robust in style than the Bishop’s Bible, it came with notes, introductions to the different books, and scriptural aids of various sorts, making it essentially the first “study bible” in history. Yet even here Tyndale continued to exert his claims. Roughly 80 percent of his translations were carried over into the Geneva Bible, confirming once again that Tyndale was indeed “the father of the English Bible,” as he is still known today.

Shortly after ascending the throne in 1603, King James I—an eccentric yet relatively erudite monarch (see David Teems’s lively biography Majestie)—received a petition signed by over one thousand Puritans. Known as the Millenary Petition, it expressed concerns over a number of issues such as vestments, “popish” ceremonies, and the Puritans’ wish that the clergy should be properly educated and that church doctrine should be grounded in scripture. Fond of theological debate, James convened the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 to discuss the petition. He rejected virtually all of the Puritans’ proposals except for one. He agreed to the publication of a new English Bible, motivated in part by his aversion to the popular Geneva Bible, some of whose notes he considered antimonarchical.

The conference resulted in the following resolution:

That a translation be made of the whole Bible, as consonant as can be to the original Hebrew and Greek; and this to be set out and printed, without any marginal notes, and only to be used in all churches of England in time of divine service.

Fifty-four men—among them the best biblical scholars and linguists in England—were put in charge of the project. At least forty-seven of them took active part in the work, which began in 1604 and concluded in 1611.

The great virtue of that translation committee was its determination not to undertake an entirely new translation but rather “to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one.” With all the previous English versions at their disposal, they did not disdain to consult, adopt, or adapt whatever they deemed worthy from the previous translations. The result of their judicious work of appropriation and revision was a version that did indeed make “one principal good one” out of the many good Bibles that had come before.

I will offer just one example of how the King James Bible made many good translations even better. Here is Tyndale’s version (in our modern spelling) of the famous definition of faith that occurs in the first verse of chapter 11 of the pseudo-Pauline Letter to the Hebrews (“pseudo-Pauline” because Paul was not in fact its author):

Faith is the sure confidence of things, which are hoped for, & a certainty of things which are not seen.

The Geneva Bible version:

Now faith is the ground of things, which are hoped for, and the evidence of things which are not seen.

The 1611 King James Version:

Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

The King James Version both retrieves and improves on its predecessors in two ways. By eliminating the words “which are”—which occur twice in the earlier versions—it gives a much cleaner and poetically compact rendition of the verse. Tyndale’s “sure confidence” is a very loose translation of the Greek hypostasis, which means literally “standing under” (hypo, under + histasthai, stand, middle voice of histanai, cause to stand). The Geneva version’s “ground” is a much closer approximation, yet the KJB’s choice of “substance” is brilliant. Not only does “substance” mean literally “standing under,” it also comes with a host of religious associations and connotations—especially in the context of the Reformation’s vexed debates about the “transubstantiation” of the Eucharistic wafer by the priest during Mass.

Meanwhile the KJB retains the Geneva Bible’s “evidence,” an English word that stretches the meaning of the Greek elenchus, to be sure (elenchus means, among other things, refutation of an argument by proving the contrary of its conclusion), yet the word “evidence” preserves, if only latently, the dynamic interplay between proof and refutation in the context of a definition of faith. Faith is the evidence of a truth that faith cannot show to be true, since it cannot be seen in the demonstrative mode. In that respect it is the evidence of what can neither be proved nor refuted by what Paul, in the passage cited from I Corinthians, calls “the wisdom of the wise” and the “understanding of the prudent.”

Having mentioned that the Geneva Bible was used by Shakespeare, let me take this occasion to express my conviction that Othello is an extended pun on this pseudo-Pauline definition of faith. The word “faith”—in a variety of semantic contexts—punctuates that play from beginning to end, ever more intensely as Othello’s doubts about Desdemona’s faithfulness turn into false certainty. Through Iago’s manipulation of the evidence, Othello sees something that is not there. Yet it is Othello’s own lack of faith in her that causes him to see in Desdemona’s purloined handkerchief the material evidence of things not seen, i.e., her betrayal of him, which never took place.

I believe that the verse in question from the Letter to the Hebrews also seeped into the latent recesses of the opening sentence of the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” We should recall here that Jefferson and his colleagues made a minor revision to that sentence before presenting their draft to Congress. The prerevised version read: “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable….” The difference between “self-evident” and “sacred” is considerable. From the point of view of enlightened reason, a self-evident truth is manifestly true. Its veracity does not need to appeal to external authority. A sacred truth, by contrast, has a transcendent source that lies beyond the bounds of confirmation by reason.

Yet what could be less self-evident—when one looked at history, nature, or human society in the eighteenth century—than the equality of men or government by consent of the governed? Everywhere one turned one saw only inequality and oppression, nowhere inalienable rights and consent of the governed. To whom, then, are the Declaration’s truths self-evident? To those who are making the declaration—those who are declaring their faith in truths they deem self-evident. The Declaration of Independence is at bottom a declaration of faith in a certain type of government not yet seen on this earth.

The Italian writer Italo Calvino once defined a classic as “a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.” In The Rise and Fall of the Bible, Timothy Beal reminds us that the Bible is not really a book at all but “a collection of texts written by many different people, mostly anonymous, in many different translations, and in many different historical and social contexts.” The King James Bible is only one version of this great library, or bibliotheca, as Saint Jerome called scripture in the fifth century. Yet book or not, the King James Version surely fits Calvino’s definition of a classic. Whether it speaks in its own voice, or through the countless other voices that have kept its words alive, it still has not finished saying what it has to say.

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

Václav Havel (1936–2011)

The Republican Nightmare