1.

Halfway through the first section of RainForest, the work that Merce Cunningham choreographed for his splendid company in 1968, the character initially played by Merce sits peaceably downstage left, while the character originally danced by Barbara Lloyd Dilley leans against him in a position of luxurious repose, her head on his shoulder. A minute earlier, they have prowled around each other in tight circles like dogs, or lions. Great moments of stillness pass, and then the character danced back then by the much younger Albert Reid strides over and sits in close proximity to Merce and Barbara. In a flash, she is kneeling next to him, having transferred her head from Merce’s shoulder to his. Merce squats in alarm next to this new couple for a moment, but the situation is becoming highly fluid.

Within minutes the character danced by the kingly and long-legged Gus Solomons will stride, stiff and purposeful, toward where Barbara is lying and slowly, carefully, get down on all fours and, with the crown of his head, push Barbara right below her shoulder blade, and then underneath her hip bone, until she rolls languorously away from him. He’ll push her again, she’ll roll again, and the initial moment of union between Merce and Barbara will have passed, as moments do in cities and jungles, possibilities arriving and breaking up and reforming again as something else, to our regret or perhaps, sometimes, our joy.

It is sequences of pure emotional transparency like this one, and an ongoing flow of moments of sheer beauty, that kept packed audiences cheering and clapping through endless curtain calls during the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s last Paris season in December. But it was also nostalgia for what was about to be lost forever. Merce Cunningham died on July 26, 2009, at the age of ninety, and, in a stunning act of artistic self-immolation, the creator of some of the twentieth century’s most moving dance works decided that his company should not outlive him. With the backing of the board of trustees of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, he agreed that following his death, the company would embark on one final world tour, and then everything would go. Company, studio, school, musicians, dancers—the entire institution created with such great effort by Merce over a fifty-year period—closed down after a final performance at the Park Avenue Armory on New Year’s Eve. It was the Merce thing to do: evanescence, the laws of chance, and ego, too, always guided him.

Merce developed the guiding elements of his art with his lifelong partner, John Cage, and with members of his circle—among others, the composers Earle Brown, David Tudor, and Morton Feldman, and his frequent collaborators on stage design, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. The group believed that dance, music, and visual arts could coexist together on a stage, but should not be forced to depend on each other (as, to put it broadly, the music, steps, and costumes do in Swan Lake). But while all this philosophy could easily have resulted in New Age meditational fuzz, the actual product was harsher. The musicians and artists collaborating with Merce worked in a late-twentieth-century mode, which seemed to call for a more fragmented, more industrial, brutal art. This is the principal reason why, despite the cool beauty of the actual dancing, Cunningham performances often caused members of the audience to flee.

Using the I Ching and, later, a computer to enforce the randomness of movements and sequences, Merce nearly killed his dancers and himself in an assault on the impossible: to interrupt the body’s logical way of shifting from one movement to the next; from one single direction in space the body would move to an unpredictable multiplicity of fronts. Like other midcentury choreographers, he unmoored dancing from narrative, but until he started working with computers, he did not eliminate character from his dances: bodies were the characters. In RainForest, Gus Solomons’s body dictated one story; someone dancing the same role years later told another story. Merce insisted throughout that his dances were not abstract: “I have never seen an abstract human body,” he often remarked. He himself danced like a man on fire.

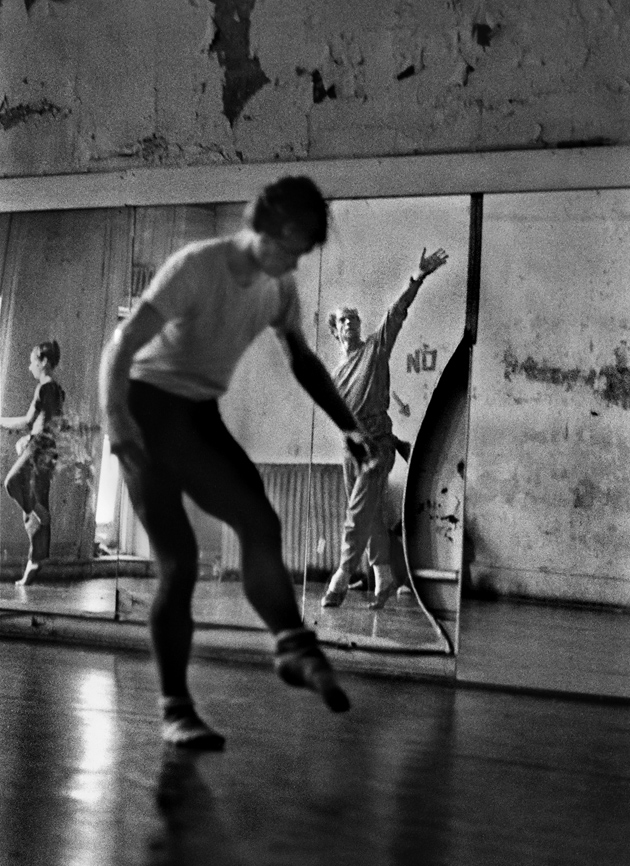

His mode of operation was, however, cool. Those of us who were privileged to study with him at whatever point in his long career will cherish forever the physical challenges he posed for a dancer, the intellectual alertness required, and the lack of drama involved in conveying his wishes. But we loved Merce’s old-fashioned courtesy, too. Once, at the start of the Szechuan food craze, I walked into a formica-table Szechuan restaurant on Chatham Square and found Merce with Cage and, if I recall correctly, Buckminster Fuller. I was a bashful teenager, but he stood up to greet me as if I were a great lady. Perhaps I loved most of all the times that I showed up at the studio a little early for class and found him already there in his practice clothes, thoughtfully sweeping the floor.

Advertisement

Followers like myself also loved his headlong determination to make every piece new, even if it meant losing audience members unwilling to work that hard for the payoff: his brother once asked, “Merce, when are you going to make something the public likes?” We loved Merce’s courage: he showed up for work when he was exhausted, when he was injured, when he was suffering, and as several former dancers who flew over to the Paris season in December to say good-bye recalled, he never just went through the motions even in rehearsal; he always danced full-out. In his later years, wheelchair-bound with rheumatoid arthritis, he turned to computerized movement programs to choreograph, and was working out a new dance in his mind the day he died.

He was for so long an innovator that one forgot how much twentieth-century American dance he carried in his body. He started performing in his native Centralia, Washington, at age fourteen, at a dance academy that taught “toe-dancing” along with tap and other vaudeville forms. A photograph from those early times shows a bright-faced, curly-haired boy who could have popped up in movies of the time as the cheerful soda jerk behind the counter who never gets the girl. He advanced quickly: one of the academy’s dance program’s featured Mercier Cunningham (his given name) in a “Russian Dance.” Years later he would reprise, slo-mo, that dance’s squatting kicks in the opening minute of his first group masterpiece, Suite for Five (1956–1958).

But Merce’s real specialty was exhibition ballroom dancing, and another photograph from the period shows us a different person, in a tux, leaning elegantly over his young partner in a way that would be familiar to audiences right to the end of his performing life, his gaze utterly concentrated on the girl. Merce loved partnering, and he rarely looked more relaxed or focused onstage than when he was swooping a woman off her feet.

He tried college and hated it, and so, with the approval of his remarkably tolerant family, he enrolled at an avant-garde arts academy in Seattle founded by the pioneer pedagogue Nellie Cornish and known today as the Cornish College of the Arts. Cunningham had his first lessons in the dance technique of Martha Graham there, and during the summer he got to train in Los Angeles with an influential West Coast choreographer, Lester Horton, who used to rehearse with a cigar in one hand. At Cornish, Merce was also fascinated by the work of a performer who had studied Native American spirit dancing. He observed closely the technique of Uday Shankar, a visiting dancer from India.

Indeed, it’s hard to think of a type of dance—flamenco, nautch, hornpipe—that the young Merce would not have had at least an idea of by the end of his second year at Miss Cornish’s school, in 1938. Photographs show us a nineteen-year-old who is already, unmistakably, the great performer Merce Cunningham would become. The intense, dramatic face, the easy soaring leap, the technical facility, the love of challenges, the weird grace, are all there.

At Cornish Cunningham found the prototype for the partner he would always turn to onstage: an instinctively graceful and “perfectly beautiful” woman called Dorothy Herrmann. To judge from the photographs, she seems to have shared with Carolyn Brown, the dancer who was to become his favorite instrument, a lovely feminine way of making shapes, and stupendous strength and clarity of movement. (Brown’s departure from the company in 1972 meant a “profound change” in his work, meaning—I am speculating here—that he became much more interested in steps and less so in the character of individual bodies onstage.) It was at Cornish that he began his practice of yoga, and that he had his first encounters with Zen Buddhism, which would become a guiding path for his life, as it was for so many of his contemporaries in the arts. And it was at Cornish that he met John Cage.*

Cage later remembered that his first impression of Cunningham had to do with his “extraordinary elevation” (high jump) and “appetite for dance.” But there was more than that. Cage was married at the time, performing his wildly experimental music with his wife, an Alaskan-born artist by the name of Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff. He always looked older, but he was barely twenty-six years old, a young man also hungry for art, and there was Merce with his long thighs and big hands and hungry face.

Advertisement

Cage stayed married for several more years, sometimes living in the same city as Merce and sometimes not. The deceptions and eventual breakup with Xenia were messy and unspeakably painful, Cage later acknowledged, and perhaps they sealed in Merce forever the need for cool distance in his relations with others. In any event, Merce and Cage gave their first concert together—the music and dance apart—in 1944, and Cage was divorced in 1945. With some interruptions, he and Merce performed and lived together until the composer’s death in 1992.

2.

The dancer’s discipline, his daily rite, can be looked at in this way: to make it possible for the spirit to move through his limbs and to extend its manifestations into space, with all its freedom and necessity. I am no more philosophical than my legs, but from them I sense this fact: that they are infused with energy that can be released in movement (to appear to be motionless is its own kind of intoxicating movement)—that the shape the movement takes is beyond the fathoming of my mind’s analysis but clear to my eyes and rich to my imagination…. In other words, a man is a two-legged creature—more basically and more intimately—than he is anything else. And his legs speak more than they “know.”

Forty-seven years after writing this statement in 1952, Merce made BIPED. In the Seventies he had begun to create works specifically for video, and in 1989 he started to choreograph with the aid of a motion-capture computer program, first as a way of arbitrarily putting dance sequences together so that he could then discover new transitions and possibilities, and then, as his body was destroyed by rheumatoid arthritis, as a way to continue making dances, particularly after he stopped performing in the mid-1990s. BIPED was the summation of everything he had learned about dance and technology, a shimmering, endlessly ambitious work. It’s too long; an entire section with a silly costume change and far too much hopping could be lost to no one’s sorrow. It’s full of unnecessary twitchy movements that are there only because a computer came up with them. The music is treacly, particularly for those of us brought up on the chewier fare of the John Cage era, but who cares?

The glorious lighting design by Aaron Copp, the magical rear scrim into which people vanish only to reappear, the front scrim on which creatures made of light scurry and twirl, all have equal place with the dancers, whose flesh emerges from iridescent costumes designed by Suzanne Gallo to look as if they were made of fish scales. We see people spinning with their heads thrown back as if they were learning to contemplate the stars. Young women line up in the graceful poses of Hindu temple dancers. Etruscan warriors engage in funeral games. It is both a spectacular and moving masterpiece, made at the cutting edge of dance technology.

No doubt BIPED and some of the other great choreographies in repertory during the final tour will be seen again: ballet and modern dance companies around the world already perform several of his works, and during the next few years they will most certainly be carefully staged by former Cunningham dancers with artists who may have seen the Cunningham company perform, and know what a singular level of technical virtuosity, speed, emotional commitment, and drive is expected of them.

But even in the best of cases it seems impossible that one will ever again see not just the steps, but the movement. The Cunningham studio, where several classes a day were taught in his rigorous and highly effective dance technique, will close down in April. Robert Swinston, a longtime company member who essentially replaced Merce as its artistic director, will continue to teach intensive workshops all over the world, but mastering the technique is a question of years, not weeks. Whether Merce should have been helped by his board to torch everything he worked so killingly hard to create will be debated for a long time, along with the question of why he did it. The company faced a devastating economic crisis following the 2008 recession, and sometimes it was difficult to fill a theater or get bookings. But mostly, the man who loved limitations and difficulties was too old and frail to take charge of the crisis.

“I never saw Merce express an emotion,” one of his dancers said last summer at a Merce event at Lincoln Center, but watching him on stage it seemed to me that he was a man capable of great fury. In many dances, like Summerspace, Suite for Five, and RainForest, the curtain drops when Merce—or the dancer playing his character—walks off the stage. In Quartet, created in 1982, when he was already physically feeble, there are actually five dancers. The fifth is Merce, eerily reembodied during its final performances by Robert Swinston, drooping gut and all. He is invisible, hobbled, prophetic, as the other four dancers fan out and dance past him, sometimes even encircling him without noticing that he’s there. Merce’s solo of despair and rage ends when he walks off upstage left, and so does the dance. Perhaps that’s the ending he needed this time, too.

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

Václav Havel (1936–2011)

The Republican Nightmare

-

*

I owe the information and perspective on Cunningham’s formative years and his thinking to the indispensable Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years, by David Vaughan (Aperture, 1997). The book is to be reissued on Merce’s birthday (April 16, 2012) as an app for tablet computers, complete with video links. The book-length interview with Cunningham in Jacqueline Lesschaeve’s The Dancer and the Dance (Marion Boyars, 1985) and Carolyn Brown’s lively memoir of her years with Merce, Chance and Circumstance (Knopf, 2007), are also extremely useful. For anyone already nostalgic for Merce and his puckish humor, his thoughtfulness, his studio at Westbeth, and his beautiful dancers, the online series Mondays with Merce by Nancy Dalva can be found at www.merce.org/about/mondays-with-merce.php. ↩