I first heard of Patti Smith in 1971, when I was seventeen. The occasion was an unsigned half-column item in the New York Flyer, a short-lived local supplement to Rolling Stone, marking the single performance of Cowboy Mouth, a play she cowrote and costarred in with Sam Shepard, and it was possibly her first appearance in the press. What caught my eye and made me save the clipping—besides the accompanying photo of her in a striped jersey, looking vulnerable—was her boast, “I’m one of the best poets in rock and roll.” At the time, I didn’t just think I was the best poet in rock and roll; I thought I was the only one, for all that my practice consisted solely of playing “Sister Ray” by the Velvet Underground very loud on the stereo and filling notebook pages with drivel that naturally fell into the song’s meter. (I later discovered that I was just one of hundreds, maybe thousands, of teenagers around the world doing essentially the same thing.)

Very soon I began seeing her byline in the rock papers, the major intellectual conduits of youth at that time. Her contributions were not ordinary. She reviewed a Lotte Lenya anthology for Rolling Stone (“[She] lays the queen’s cards on the table and plays them with kisses and spit and a ribbon round her throat”). She wrote a half-page letter to the editors of Crawdaddy contrasting that magazine’s praise for assorted mediocrities with the true neglected stars out in the world:

Best of everything there was

and everything there is to come

is often undocumented.

Lost in the cosmos of time.

On the subway I saw the most beautiful girl.

In an unknown pool hall I saw the greatest shot in history.

A nameless blonde boy in a mohair sweater.

A drawing in a Paris alleyway. Second only to Dubuffet.

Creem devoted four pages to a portfolio of her poems (“Christ died for somebodies sins/but not mine/melting in a pot of thieves/wild card up the sleeve/thick heart of stone/my sins my own…”—if this sounds familiar, you expect the next line to be “they belong to me,” but it’s not there yet).

Then in November 1973, a small ad in The Village Voice announced that she would be performing at Le Jardin, a gay disco in the roof garden of the Hotel Diplomat on West 43rd Street, in honor of “the first true poet and seer,” Arthur Rimbaud. Accompanied on guitar by Lenny Kaye, a rock critic familiar from his job behind the cash register at Village Oldies on Bleecker Street, she read and talk-sang: Kurt Weill’s “Speak Low,” Hank Ballard’s “Annie Had a Baby,” a version of Édith Piaf’s “Mon vieux Lucien,” and twenty-two more poems, four of them about Rimbaud. She was skinny, quick-witted, disarmingly unprofessional, alternating between stand-up patter, bardic intonations, and the hypnotic emotional sway of a chanteuse, and she was sexy in an androgynous way I hadn’t encountered before. The elements cohered convincingly; she seemed both entirely new and somehow long-anticipated. For me at nineteen, the show was an epiphany.

Soon I bought her chapbooks Seventh Heaven1 and Wītt,2 which between them contained most of the poems she performed, as well as her first record, a 45-rpm single, “Hey Joe” with “Piss Factory” on the B side, on the small Mer label (1974). By then the poets I liked best and tried to emulate—Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Ted Berrigan, Ron Padgett—spoke to the eye and the refined internal ear. Apart from Allen Ginsberg and Helen Adam it was hard to think of contemporary poets who honored poetry’s ancient connection to song. And while many pop critics of the time insisted that rock lyrics were poetry, not much of the stuff actually held up on the page, paradoxically because so much of it was choked with aspirational fustian. (“The idea that poetry—a concept not too well understood—can be incorporated into rock…is old-fashioned and literary in the worst sense,”3 wrote Robert Christgau, a cannier critic.)

Smith, though, was aiming at once higher and lower than Paul Simon or Jim Morrison. Her verses were resolutely demotic, even as she played with the imagery that Rimbaud drew from the Bible and Eliphas Lévi and fairy tales and illustrated geographies, and she deployed this imagery even as she devoted poems to Edie Sedgwick, Marianne Faithfull, and Anita Pallenberg. She seemed to write with a rhythm section starting and stopping in her head, so that her work unpredictably ran the gamut from music to prose, sometimes within the same poem—much like Rimbaud’s in A Season in Hell.

Advertisement

The record, especially its B side, represented her more fully than the publications did, matching the power and surprise of her live performances.4 Her delivery was girlish but not what you’d call frail—it owed a lot to the girl-hoodlum vibe imparted by 1960s girl groups like the Ronettes and the Shangri-Las—and she marked off cadences in short insistent jabs that sounded both Beat (more the Robert Creeley–inspired wing than the Whitman-influenced long-breath school) and rhythm and blues, and she would sometimes depart on tangents that appeared to be improvised on the spot. No item in her repertoire was delivered quite the same way twice. As she appeared, usually backed by Kaye and the pianist Richard Sohl, at disparate venues all over town—a poetry café, a piano bar, a folk music club, a jazz dive—I attended nearly every gig, once dropping an entire week’s paycheck in the process.

Early in 1975, I heard she was performing with some semblance of a band at a bar called CBGB. There had not been a regular venue for rock bands in lower Manhattan since the 1973 collapse of the Mercer Arts Center (home of the New York Dolls, among others); even Max’s Kansas City, quondam domain of the Velvet Underground, had become more of a cabaret—Smith had done a stint there herself. CBGB, successor of a century’s lineage of Bowery saloons on that site, was a tunnel-like space with a long bar down the right side and a recently constructed stage at the far end watched over by large photo-blowups of Jimmie Rodgers and a bevy of Mack Sennett bathing beauties.

The opening act was Television, whose members had built the stage and encouraged the bar’s owner in a new booking policy, shedding the styles alluded to in the club’s acronym, “Country, Bluegrass & Blues.” Smith’s band was skeletal, while her songs hovered somewhere between spoken-word pieces and pop songs. She covered the Marvelettes’ “The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game” and the Velvet Underground’s “We’re Gonna Have a Real Good Time Together.” She was stretching her vocal cords, talking less and singing more.

I went back many times after that, observing the band filling out and the songs taking shape. Meanwhile, the club was becoming the epicenter of a phenomenon that before year’s end had come to be called “punk,” in reference to the primitive teenage rock and roll of the mid-1960s, which had been surveyed in a 1972 anthology, Nuggets, compiled by Kaye. The house aesthetic matched the simplicity and directness of that music, and virtually every one of the bands that played CBGB covered the classics of the genre, often at the beginning of sets as ritual invocation and starting gun. The Ramones played the Rivieras’ “California Sun”; Talking Heads played Question Mark and the Mysterians’ “96 Tears”; Television played the Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction.” Smith and her group yoked her poem “Oath” (“Jesus died for somebody’s sins…”) to “Gloria,” a 1964 standard by Them. The poem declares her transfer of allegiance from dogma to flesh (“So Christ/I’m giving you the good-bye/firing you tonight”), but the song manifests it, moving from recitation to singing, from the abstract to the concrete, from inwardly directed argument to outwardly directed lust. She transforms Van Morrison’s studiously functional teenage-caveman lyrics—his Gloria stands roughly five foot four, comes around at approximately midnight, and makes the singer feel nonspecifically fine—into a narrative that accrues details (“leaning on the parking meter”) and suspense (“crawling up my stair here she comes”) as it passes through increasingly frantic rhythmic sequences like a car shifting up through its gears, landing on the chorus (“G–L–O–R–I–A“) as if it were the top of a mountain.

Smith was the president of a fan club that had just one member but a hundred idols: Rimbaud, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Keith Richards, Jackson Pollock, Isabelle Eberhardt, Brian Jones, Georgia O’Keeffe, William Burroughs, Renée Falconetti (Joan of Arc in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 movie), not to mention Johnny Carson. She evoked these personalities, and more, in her songs and poems and broadsides and chapbooks, in her stage patter, in interviews, and she was not at all coy about enumerating her specific debts to them. She made a point, that is, of publicly enacting a process that most artists keep to themselves. This was doubly brave of her, since as a woman at that time declaring herself to be something more than a singer and decorative stage presence she faced a certain amount of derision anyway. It was easy for lazy journalists to caricature her as a stringbean who looked like Keith Richards, emitted Dylanish word salads, and dropped names—a high-concept tribute act of some sort, very wet behind the ears. But then her first album, Horses, came out in November 1975, and silenced most of the scoffers.

Advertisement

The record’s cover, featuring Robert Mapplethorpe’s famous image of Smith in a man’s white shirt and undone necktie, jacket slung over her shoulder, was a declaration of female swagger such as had not been seen since Marlene Dietrich’s tuxedo. Inside was the culmination of all those years spent trying out ideas in assorted raggedy clubs. There were songs for each of her two sisters, an elegy for Jimi Hendrix, an uptempo rock number called “Free Money,” and “Gloria (in Excelsis Deo),” as it had come to be called. And there were a couple of other big poem/song hybrids. “Birdland” begins with a mesmerizing and heartbreaking monologue, inspired by Peter Reich’s Book of Dreams, of a young boy at his father’s funeral, awaiting his—Wilhelm Reich’s—return for him in a UFO. “Land” is Chris Kenner’s perdurable “Land of 1000 Dances” bracketed by the story of Johnny—essentially William Burroughs’s Johnny in The Wild Boys: sex object and all-American Kilroy—and his delirious visions of horses turning into waves turning into horses. “Go Rimbaud and go Johnny go!” she shouted, and the sound bite would be permanently affixed to her image.

It was Rimbaud who wrote, in his famous “letter of the seer” to Paul Demeny, May 15, 1871:

When the endless servitude of woman is finally shattered, when she comes to live by and for herself, man—up to then abominable—having released her, she too will be a poet! Woman will find a portion of the unknown! Will her world of ideas differ from ours? She will find strange, unfathomable, repulsive, delicious things.

In the “Notice” at the beginning of Wītt, Smith wrote: “These ravings, observations, etc. come from one who, beyond vows, is without mother, gender, or country who attempts to bleed from the word a system, a space base.”

The system Smith bled from language was an oracular nonstop cavalcade of words hurled like sixteenth notes, powered by a rhythm imposed by force of will. While she engaged with prosody and songcraft a bit in her early years—“Death comes sweeping through the hallway like a lady’s dress/Death comes riding down the highway in its Sunday best” (“Fire of Unknown Origin”)—by the time she fronted a full band she seemed less interested in singing lyrics, preferring to chant simple refrains or to deploy her words as a discordant, wild-card instrument, a version of what the critic Lester Bangs called “skronk.” She made capital use of jukebox slang at first, but increasingly she sought biblical allusions and cadences, echoed the incantatory Rastafarian style of Jamaican talk-over artists such as Tappa Zukie, and she favored the orientalism in Rimbaud (whose father after all translated the Koran).

The sexual tension in her work naturally strove toward orgasm, the musical tension ached for release, and the punk style she helped initiate was, thanks to the Sex Pistols and others, becoming increasingly confrontational and even violent in its stance. It followed that she would be ever more inclined toward making things go boom. In song after song, yearning for transcendence, she found satisfaction in accelerating tempos and flurries of highly charged verbiage that mimed conflagration. Robert Christgau, reviewing Horses, termed her style “apocalyptic romanticism.”

Among the consequences of this ascendant style were that she lost her humor bit by bit and took herself more seriously with every succeeding record. On the other hand, she manifestly believed in her mission as much as anyone who had ever picked up a microphone, and that belief was contagious. By 1977 or so she had become a performer so electric and charismatic that critique simply withered in the heat she exuded onstage. Her band, charmingly erratic at first, perfected their chops with constant touring; her songs were more than the sum of their parts; she rode a crest of momentum for three more albums after Horses. Then, in 1980, she did the unthinkable: at or near the height of her powers she married Fred “Sonic” Smith, late of the MC5, and retired from recording and performance to move to a Detroit suburb and become a housewife and mother.

Although she made one record with her husband in 1988, she didn’t fully emerge from her seclusion until the mid-1990s. By that time he was dead, and so were her brother; her keyboard player, Richard Sohl; and her best friend, Robert Mapplethorpe. An air of mourning unavoidably colored her writing and performance and contributed to a truly formidable gravitas—she became at once rock’s Mater Dolorosa and its Mother Courage. By now she is an institution, and it is hard to remember the air of goofy, inspired amateurism she wore for much of her first decade in the public eye—the notion that she was just like anyone else in the audience, but daring enough to mount the stage, was her crucial contribution to the punk ethos. She remains a galvanizing performer whose passion and commitment and utter lack of showbiz cynicism allow her to play every show as if it were her last. By now almost everything in her repertoire sounds like either an anthem or a hymn, and while catharsis may come cheap in rock and roll, the effect she has on her audience gives every impression of having been earned.

This has not preserved her music from a certain lugubriousness; its religiose affectations can be especially wearing on listeners at home. Then again, her written work has acquired a greater range over the years. Woolgathering, which was originally published in 1992 in Raymond Foye’s palm-size Hanuman collection, is a delightfully rambling mix of childhood memories and dream sequences, the latter with the hashish-trance lucidity of some of Paul Bowles’s stories, such as “He of the Assembly.” Rimbaud inevitably shows his face, too:

I dreamed of being a painter, but I let the image slide into a vat of pigment and pastry-foam while I bounded from temple to junkyard in pursuit of the word. A solitary shepherdess gathering bits of wool plucked by the hand of the wind from the belly of a lamb. A noun. A nun. A red. O blue.

Her most recent book of poems, Auguries of Innocence (2005, revised 2008), is rueful and sober in a way that is new for her. There are poems for her children and for Diane Arbus, a meditation on the bombing of Baghdad that drifts away for a while to consider the suicide of Virginia Woolf, a poem that eerily seems to anticipate the fall of Qaddafi (“Soon the sun will ascend over Libya./Can it matter? We have bombed/Benghazi. A dazed warhead struck/the compound of our foe lying alive,/his eyes white, black rimmed.”), and an ambitious settling of accounts with Rimbaud:

Everyone wears a corpse about their wrist. Just a bit of twine, but a corpse all the same. A dead thing proclaiming I have you and you. I snip all these things and hurl all rings in the urinal you knelt in. Your tears made it overflow. All the sewage covered the station and made you shudder. This was as close to a laugh as you could get. The image of a shit-covered wagon. You stood clad in white, trembling.

Her memoir Just Kids (2010), the account of her friendship with the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, has been justly celebrated. It is delicate and affectionate as it tells of their adventures in a New York City bohemia that now seems a century removed, of the endurance of their relationship despite his realization that he was gay, of their separate pursuits of fame, of his illness and death. It is almost too literary for its own good, since her choices of word and phrase always come down on the genteel side of the ledger: “perhaps” rather than “maybe,” “rise” rather than “stand,” “yet” rather than “but,” “one” rather than “you.” There’s hardly a contraction, outside the dialogue, in the entire book. But despite the fact that this sort of talk is patently not the way she expressed herself at the time, and that it sounds more effortful than natural on the page, it does cover the book with an appropriate hush—it sounds like someone tiptoeing through a sickroom.

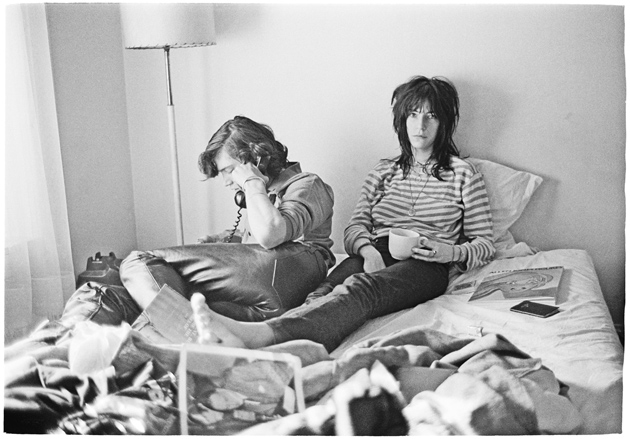

An earthier and less reverent but equally glamorous view of their life together can be seen in the photographs by Judy Linn collected in Patti Smith 1969–1976. Looking rather like stills from an unknown New Wave film, the pictures cover Smith from her early hippie days in New York to the first year or two of her fame with a remarkable consistency, displaying various ratty lofts, misguided hairstyles, improvised fashion choices, and a lot of winning and unforced self-display, the Hollywood poses of a girl who didn’t think she was beautiful. Mapplethorpe may have taken the most famous of her portraits, but many of these appeared on the covers of books and records early on, and they helped construct her image just as much. The fact that the in-between shots are included—the ones where she is out of focus or has her back turned or is squinting from cigarette smoke—contributes powerfully to the sense that the book represents a narrative and not simply a collection. It is a beautifully realized long-term project, an exquisite collaboration between photographer and subject.

Smith’s rise from gawky poet and associate scenemaker to rock star is documented and lavishly contextualized in Will Hermes’s Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, in which her early career is viewed alongside those of Bruce Springsteen, Philip Glass, Grandmaster Flash, the New York Dolls, Anthony Braxton, and dozens of others who made music in New York in the impossibly fecund 1970s and somehow wound up influencing one another, wittingly or not. Despite the broad canvas, Smith cuts an indelible figure, more vibrant than any other character surveyed. And Hermes is uninterested in genteel revisionism; you see Smith spitting, cursing, and telling an early audience: “Don’t be afraid of me. I’m just a nice little girl.”

Smith’s most recent production, Camera Solo, is an exhibition and catalog of her black-and-white Polaroids. It is not her first outing as a photographer—a similar collection, Land 250, was published in a pricey edition by the Fondation Cartier in 2008. Taken singly the pictures are unremarkable; viewed strictly as photographs they are ordinary, and sometimes blurred or oddly framed in unilluminating ways. But they are not art objects as much as they are talismans, and so they follow the line of her character and her work as established early on. Several of the pictures in Linn’s book show her walls: pictures of Dylan, Mayakovsky, Jean Genet, Blaise Cendrars, James Dean, Hank Williams, and Camus sharing space with beads and gris-gris sacs and toys and walking sticks.

On the first page of Just Kids she records her movements while Robert Mapplethorpe lay dying many miles away: “I quietly straightened my things…. The cobalt inkwell that had been his. My Persian cup, my purple heart, a tray of baby teeth.” Her photos likewise show Robert Graves’s hat, Roberto Bolaño’s chair, the Rimbaud family atlas, the beds of John Keats, Victor Hugo, and Virginia Woolf, the graves of Blake, Shelley, Whitman, Brancusi, and Modigliani.

Each picture represents some kind of transmission from the dead, and their blurriness and graininess assist in giving them the air of nineteenth-century spirit photos. It is an intensely personal collection, almost like a tour of her desk drawers, but it isn’t idle. She has obtained something from each of those figures, and by photographing their leavings she is passing along the spark. Somewhere down the line a young fan will pick up the trace. She did as much for me long ago, after all.

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

Václav Havel (1936–2011)

The Republican Nightmare