Beneath the turbulent political spectacle that has captured so much of the nation’s attention lies a more important question than who will get the Republican nomination, or even who will win in November: Will we have a democratic election this year? Will the presidential election reflect the will of the people? Will it be seen as doing so—and if not, what happens? The combination of broadscale, coordinated efforts underway to manipulate the election and the previously banned unlimited amounts of unaccountable money from private or corporate interests involved in those efforts threatens the democratic process for picking a president. The assumptions underlying that process—that there is a right to vote, that the system for nominating and electing a president is essentially fair—are at serious risk.

In all of the excitement over the Republicans’ sweep of the 2010 elections—their recapture of the House of Representatives, the decrease in the Democrats’ margin in the Senate, and the emergence of the Tea Party as a national force—most of us missed the significance of their victories in the states. The Republicans took control of both the governorship and the legislature in twelve states; ten states were already under Republican control. The Republican-controlled states undertook quite similar efforts to tilt the outcome of the presidential election in their party’s favor by denying the right to vote to groups that traditionally voted Democratic—minorities, the elderly, and students.

Of the fifteen states that in 2011 considered new voting restrictions, eight approved a requirement that people who want to vote show a government-issued photo ID, such as a driver’s license or passport, the kinds of documents that members of such groups are unlikely to have. Two states had already enacted such a requirement. (Even the Department of Motor Vehicles requires simply that people show some household bill to establish place of residence.) They reversed progress in the struggle to guarantee the right to vote that had gone on since the Civil War. This concerted effort amounts to a subversion of the democratic system of government, taking away the fundamental right to vote.

Until two years ago, there was reason to believe that through laws passed by Congress and upheld by the courts, there were at least some constraints on the part that corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals could play in federal elections through “soft money” donations. Such donations could, under very limited circumstances, be made to a party or a group organized around an issue. The donors were required to operate outside the campaigns themselves, even if the lines between them were somewhat porous. However, in 2010 a couple of major court decisions wiped away the requirement that this soft money had to be spent on “issue ads,” and removed all limits on what corporations, unions, and individuals could spend on behalf of a candidate. This led to the creation of so-called Super PACs—political action committees that collect and spend unlimited corporate or individual contributions to pay for ads that are explicitly for a specified candidate. These donations weren’t required to be disclosed until after the election. This changed everything. The 2012 election has been virtually taken over by Super PACs; the amounts they are spending are far outstripping expenditures by the candidates’ campaigns.

Though unions will play a part in campaign financing, they simply don’t have the resources that thousands of corporations have. A billionaire with a strong affection for a specific candidate no longer has to go through a party organization or a group organized around an issue to offer financial support—the women’s advocacy group Emily’s List, for instance, or the pro-business Club for Growth. The candidates and the Super PACs formed for the purpose of supporting them are ostensibly barred from collaboration; the candidates must not “request, suggest, or assent” to an ad taken by a Super PAC on his behalf, which leaves a lot of possibilities for means of communication between them, and this year’s Super PACs are noteworthy for the extent of the interlocking relationships between the candidates and those who run the Super PACs on their behalf. The election of 2012 has introduced a new kind of politics into American life.

Serious attempts to regulate the amounts of money that could be contributed to candidates began in 1974 in the wake of Watergate, when slush funds and hidden contributions collected by Richard Nixon and his wealthy backers turned up in the hands of thugs; they were blatantly used to buy ambassadorships, and as payoffs to fix legal cases and even to influence where the 1972 Republican Convention would be held. The 1974 law established public financing of presidential campaigns and set limits on contributions and expenditures in congressional elections. It limited the amounts that candidates could spend from their personal funds.

The famous but widely misunderstood Supreme Court decision Buckley v. Valeo in 1976 upheld the limits on contributions to presidential and congressional candidates, as well as to political action committees. It also upheld the limits on expenditures by presidential candidates as a condition for receiving public funds. The mistaken view that the Buckley decision said, flatly, “money equals speech” stems from the Court’s holding that limits on candidates’ personal expenditures and expenditures by independent groups violated the First Amendment protection of freedom of speech.* Thus the circumstances in which the Court in Buckley equated the spending of money to free speech were limited. The misunderstanding—or misrepresentation—of what Buckley said gave rise to a myth that continues to this day. It’s a convenient device for those who simply don’t want any limits on campaign financing.

Advertisement

The use of soft money in federal elections developed into a new avenue for money to influence politics. But numerous other ways to do so already existed and still do: contributions to the reelection funds of members of Congress; or the “leadership” PACs that members can establish to give contributions to others, thereby increasing their own power, or to a pet project in their name—limits were simply of the imagination. A wealthy Washington businessman disgusted with the impact of money on politics said to me recently, “You go in with the money and come out with the goods.”

Restrictions on the use of soft money in federal elections went back a very long way. Contributions of corporate money had been barred by a law enacted in 1907, during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Union dues were barred in the 1940s, and individual contributions had been limited by the 1974 post-Watergate campaign finance reform act. But in the 1970s soft money started to creep into federal elections, at the behest of the political parties, and with the approval of the Federal Election Commission, which had been set up to be ineffective by the 1974 act.

The McCain-Feingold Act, passed in 2002, limited the use of soft money, and the Supreme Court upheld this landmark reform in 2003. But after Samuel Alito replaced Sandra Day O’Connor in 2006, the Court took every opportunity to chip away at McCain-Feingold and then, in January 2010 in Citizens United v. FEC, by a vote of 5–4, it stripped away virtually all the constraints on the activities of corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals with respect to federal elections. The Court thus overturned a century of law.

Anthony Kennedy, in the majority opinion, famously justified the removal of limits on “independent expenditures” in favor of candidates by saying that they could operate independently of campaigns and thus “do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.” The requirement that soft money go only to issue ads was now completely eliminated. It could be used for all-out attacks on opponents, or gauzy celebrations of the candidate on whose behalf they were made, and the candidate supposedly would have nothing to do with them. In Citizens United, the “conservative” Court ruled on a broader question than had been brought before it, but it left vague the question of limits on contributions. A second controversial ruling, SpeechNow.org v. FEC, by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals a couple of months later, held that there should be no limits whatever on the contributions to groups making such expenditures. (The term Citizens United has come to refer to both cases.) The combined decisions opened up our elections to a far greater role for corporate and wealthy individuals’ money than had ever before been imaginable. And they spawned Super PACs.

The connections between the candidates and the Super PACs supporting them aren’t very well hidden. Romney’s former national political director, Carl Forti, famous for his years of efforts to get around limits on outside spending, set up the pro-Romney Super PAC Restore Our Future. Romney appeared at a fund-raising event for the Super PAC and attended a private dinner with a small group of its top donors. Restore Our Future paid an estimated $4 million for ads run in Iowa attacking Newt Gingrich just when he appeared to be a threat to Romney there.

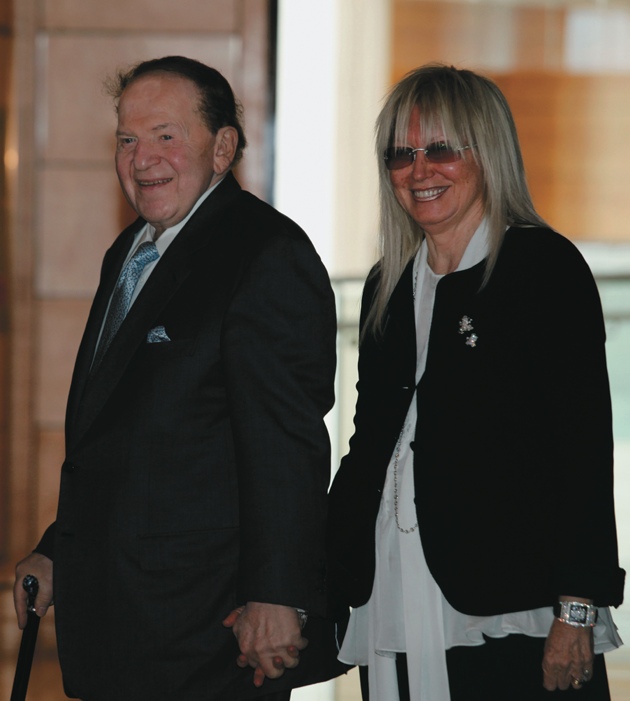

In debates in New Hampshire, both Gingrich and Romney disavowed any connection with ads by Super PACs set up on their behalf; and then they went on to recite just what was in those ads. Gingrich complained bitterly about the pro-Romney Super PAC’s ads criticizing him in Iowa. He told reporters that he was going to unleash a negative barrage against Romney in New Hampshire. Then the Super PAC Winning Our Future, run by Gingrich’s former top campaign aide, released a half-hour video (and briefer ads taken from it) attacking the Romney-led private equity firm Bain Capital for layoffs at companies Bain took over. When Gingrich’s Super PAC was running low on funds after Iowa it was rescued by Gingrich’s longtime backer, Las Vegas casino owner Sheldon Adelson. Adelson and his wife have spent at least $10 million to put Gingrich on the course to the presidency, and Gingrich has vowed to issue an executive order on his first day as president to move the American embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a cause long supported by Adelson and other strong supporters of Israel. Were Gingrich to win, Sheldon Adelson would be one of the most influential people in the country.

Advertisement

The video circulated by Gingrich’s Super PAC was savagely attacked by other Republicans and conservative commentators as an assault on the private enterprise system itself, and The Washington Post found it so error-ridden that the beleaguered Gingrich felt compelled to “call upon” the Super PAC to correct the errors or take down the ad. The Super PAC stood its ground and continued to attack Romney. Gingrich was talking to himself.

Just as the benevolent casino owner helped Gingrich stay in the race, Rick Santorum was similarly blessed. By any objective standard Santorum had no business being in the presidential race. His mediocre Senate record and his scratchy intolerance of opposing views on social issues were bound to get him in trouble. Santorum not only opposed abortion without the federally required exception for rape or the life of the mother, but he even opposed contraceptives, saying that the states should regulate them.

Having come triumphantly from Iowa, where he was first announced to have nearly tied Romney (only to have it announced more than two weeks later that he had won), Santorum found himself facing less sympathetic audiences in New Hampshire, particularly young people, and he was often met with boos. Santorum’s dismal vote in New Hampshire (he came in fifth) would ordinarily have sent a candidate home. But he was able to fight on in South Carolina thanks to the generosity of Foster Freiss, a billionaire mutual fund tycoon in Wyoming. Freiss gave the Santorum Super PAC the Red, White, and Blue Fund $1 million to keep going. According to Politico, Freiss issued instructions on the types of ads it should run while traveling in Santorum’s entourage.

The Super PACs are such a blatant example of the outsize role that big money is playing in the 2012 election that they quickly met with considerable public outrage. And they came to represent much that’s wrong with our political system. Numerous people and organizations have tried to figure out how to get rid of them, and though there is no ready solution, there are numerous efforts to find ways to overcome the inestimable damage done by Citizens United. Responsible and irresponsible solutions have been proposed.

The most popular and most wrongheaded proposal is to amend the First Amendment to allow restrictions on spending in favor of or against a specific candidate. At least a dozen versions of this proposal are floating about, some offered by groups active in political reform such as Common Cause and Public Citizen, and also by individuals—all of whom should know better than to go down this quite dangerous road. The fatal flaw in all such suggestions is the assumption that the forces of good will remain in control of any tinkering with the First Amendment.

To submit the Constitution to the political process is to put it in danger of being opened up to the popular movements of the moment. Serious students of both campaign finance reform and the Constitution whom I have talked to are very troubled by this approach. A respected member of this group, speaking without attribution because he wishes to make no enemies in a tight-knit but competitive world, calls the effort to overturn Citizens United by changing the First Amendment “a fool’s errand.” He and a number of others point out that the idea of fixing the First Amendment in order to ban corporate funds, as several of these proposals aim to do, is altogether likely to lead to those funds being put into another form of contribution and still finding their way into the campaigns.

And it sets a very bad precedent. The Founders in Philadelphia wisely made it difficult to change this core document, by requiring the vote of two thirds of both the Senate and the House and ratification by three fourths of the states. They sought to protect the Constitution from being subject to shifts in popular opinion. Once the precedent is set, what is to keep countervailing forces from pressing for, say, a change in the First Amendment that would remove what remains of the constitutional wall between church and state?

A couple of approaches to trying to correct the wrongheadedness of Citizens United without fiddling with the Constitution have been put forward. Fred Wertheimer, of the organization Democracy 21, who has worked in the campaign finance reform field since the early Seventies, may have come up with a useful way of getting Super PACs out of our elections. Wertheimer collected evidence of the interconnections between the campaigns and the candidates, and in a letter on January 10 to Attorney General Eric Holder requested that the Justice Department examine the question of whether it did not follow that the candidates had a hand in setting up the Super PACs. Were the Justice Department to find evidence of Wertheimer’s supposition, a criminal suit could be brought against the offending officials. He also argued that these kinds of contributions to a candidate’s political committees should be held to the $2,500 limit set by the 1974 law that is still in place.

But the Justice Department—and the president it serves—might be reluctant to bring a criminal suit against officials who established Super PACs. (A president might have benefited from one.) Another route would be through new legislation to assure the independence of the Super PACs. But even if this could be achieved another serious problem would arise: political consultants could be making their own decisions about what would help their candidates, who could lose control of their own campaigns.

It’s possible that the growing public revulsion against the huge new infusions of money being poured into the election contest—distorting it, prolonging it, and subjecting the candidates to far greater obligations than ever to their big donors—will shame politicians in Washington into putting a stop to this form of corruption of the election process. If they had the courage to eliminate the Super PACs, which under Buckley could be done in connection with public financing, that would restore the primacy of the system that has been in effect since 1974, which provided such financing for presidential elections.

The abuses of soft money could be curbed in a way that doesn’t violate constitutional principle. The amount of money provided by public financing might be deemed insufficient to induce presidential candidates to stay within the system—it would also limit the amount that they could spend. In 2008, Barack Obama turned down public financing so that he could raise more money on his own. But the amount of money the candidate would receive could be enhanced by partial public financing, in which limited individual contributions would be matched by public funds. This would enable candidates to have a floor of sufficient financing to assure a competitive race.

Backers of this proposal say the incentive for future presidential candidates to accept such financing would come from political pressure establishing a “new norm” that would encourage such behavior. It’s too late to rescue this election from the appalling imposition of Super PACs. Strong public pressure would have to be brought against the president and Congress so that there would be sufficient time to fix this situation even before the next presidential election.

Ever since the controversial recount in Florida in 2000, through their political control of numerous states, Republicans have mounted a nationwide and organized effort to rig state election laws in order to tip the outcome in November. (This is not to say that Democrats are innocents, but there is scant evidence of a parallel effort.) The goal of this pernicious effort is to deny the right to vote to minorities, the poor, the elderly, and students—all groups inclined to vote Democratic.

In all, since the 2010 election twenty laws of varying types have been adopted in fourteen states that will have the effect of limiting access to the voting place. Republicans are so much in favor of voter ID laws that the Bush administration joined the state of Indiana in successfully defending its law, enacted in 2005—the first in the nation and the start of a trend. Though the Supreme Court upheld the Indiana law, it commented on its rationale—offered in defense of all these efforts—by saying there was no evidence of voter fraud in all of the state’s history. The more recent measures are stricter about what sort of ID can qualify someone to vote: a few states have banned student IDs, and Social Security cards are no longer accepted. The Obama Justice Department has moved to block voter ID laws in South Carolina. According to information gathered by the Brennan Center for Justice, which has done comprehensive work in the field of protecting citizens’ rights, 11 percent of American citizens, or over 21 million people, don’t possess a government-issued photo ID.

Another device for suppressing the vote is to require proof of citizenship, such as a birth certificate, in order to register. Maine and Ohio have passed laws ending same-day registration; five states have passed laws to restrict early voting; and three states have limited voter registration drives. Florida has been particularly tough on these and the percentage of registered voters in the state has been dropping precipitously. According to the Brennan Center at least nine states have attempted to make it harder to vote by introducing bills reducing the period for early voting and limiting the opportunity to vote by absentee ballot.

Wisconsin moved its primary to a date when college students would be on a break. Some states have reduced the number of polling places, making them harder to reach for people without transportation, and in order to make it more difficult to obtain a driver’s license Wisconsin reduced the number of DMV offices.

Defenders of these laws argue that they’re essential for preventing voter fraud—but in fact there hasn’t been solid proof of such a problem. Voter fraud has been a Republican obsession, fantastical or not. Officials of the George W. Bush administration insisted that it was widespread, and in 2007 the Bush White House ordered the Justice Department to fire seven US attorneys—Bush appointees all—several on grounds of failing to pursue charges of voter fraud.

Some of the fired US attorneys said that they had seen no serious evidence of such a crime. There are rules against launching investigations of voting groups close to an election lest it amount to voter intimidation. It was later found that the Bush administration had been calling for voter fraud prosecution in the parts of the country of the greatest importance to George W. Bush’s reelection in 2004, and “voter fraud” was a useful talking point for Karl Rove and others. The Justice Department inspector general later said that the firings of the US attorneys were “fundamentally flawed” and “raised doubts about the integrity of Department prosecution decisions.” Other ruses were employed to discourage voting (such as telling blacks the wrong day of an election).

Republicans have made a particular target of ACORN, an organization made up of community-based organizers whose activities included voter registration of low-income people. ACORN volunteers were paid according to the numbers they registered, and some of their registrations were found to be invalid. Seventy ACORN workers have been convicted of adding false names to voter roles. (However, if, to take one example, Mickey Mouse were registered, he wouldn’t be likely to show up to vote; if one person were registered three times, she would likely be able to vote only once.) Registration fraud is a different thing than voter fraud, but still ACORN brought disgrace to efforts to improve voter participation. It is now shut down. But nothing was found that warranted the widespread pattern of deliberate efforts by Republicans to suppress voting by poorer groups. The Republicans took political advantage of the opportunity handed them by ACORN’s sloppy and illegal actions.

The laws on voter ID in Republican-controlled states have been quite similar. Model bills on this and a number of subjects were provided by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an organization of multinational and other large corporations and conservative federal and state legislators. ALEC also receives major funding from the immensely rich Koch brothers, who back a number of conservative causes. The Koch brothers’ support of ALEC has expanded their influence in Republican states.

Governors and legislators introduce ALEC’s model bills as their own, with no acknowledgment of ALEC, exemplifying their leadership qualities. Legislators who succeed in getting the legislation through Congress are the featured speakers or are given awards at ALEC meetings. ALEC funds supported the election of some Republican governors who have been prominent in trying to reduce the power of public employee unions: they include John Kasich of Ohio, Scott Walker of Wisconsin, and Janice Brewer of Arizona. Another ALEC goal is the dismantling of campaign finance laws.

Citizens are now faced with evidence of the growing power of organized moneyed interests in the electoral system at the same time that the nation is more aware than ever that the inequality among income groups has grown dramatically and economic difficulties are persistent. This is a dangerous brew. Political power is shifting to the very moneyed interests that four decades of reform effort have tried to contain. The election system is being reshaped by the Super PACs and the greatly increased power of those who contribute to them to choose the candidates who best suit their purposes. But little attention is being paid to the fact that our system of electing a president is under siege. While the political press is excitedly telling us how the polls on Friday compare with the ones on Tuesday, little notice is taken of the danger to the democratic system itself.

Much of the citizenry has become more restive—less accepting of the way things are. Can an election that’s being subjected to such seriously self-interested contortions be accepted by the public as having been arrived at in a fair manner? And what will happen if it can’t?

—January 24, 2012

This Issue

February 23, 2012

Beautiful, Aesthetic, Erotic

The Super Power of Franz Liszt