George Wilcken Romney, the former automobile executive who became the centrist Republican governor of Michigan in 1963, was considered a presidential possibility leading up to the 1964 election. Moderate Republicans around the country were getting awfully nervous about this Goldwater fellow and seeking out plausible alternatives. But Romney, a tall and square-jawed man with impressive hair, had made a commitment to the voters of his state that he would serve four years, and Romney was a man who meant what he said, so a 1964 run was out of the question. The task of opposing Barry Goldwater fell to other moderates—Nelson Rockefeller and Pennsylvania’s William Scranton. Romney did, however, leave his mark on the campaign: having deemed Goldwater an enemy of civil rights, which he backed ardently, he walked out of the party’s convention at San Francisco’s Cow Palace. He had his seventeen-year-old youngest son, Mitt, in tow, and thus Mitt, too, occasionally gets credit (at www .aboutmittromney.com, for starters) for stalking away from his party on a matter of the highest principle.1

Today, as the younger Romney struggles to secure the GOP nomination that seemed his for the taking until his crushing loss to Newt Gingrich in South Carolina, to think about that anecdote and his father’s towering influence on him, to read these two balanced but essentially unflattering books, and to watch Willard Mitt Romney run a campaign in which he has charged as hard and fast to the right as he could on almost every issue you can think of lead inevitably to comparisons between the two Romneys, comparisons in which the younger Romney comes up dramatically short.

Mitt Romney, as the Massachusetts governor who passed health care legislation, had been a leader, just a few years ago, of the GOP’s now much-diminished moderate wing. At the 2008 GOP convention in St. Paul, Romney’s party took a number of positions completely at odds with those he had taken as governor, on abortion, gay rights, stem-cell research, and other matters, and adopted other extremist rallying cries, like the infamous “Drill, Baby, Drill!” chant, which thundered maniacally (I was there) through the hall when Sarah Palin spoke, as if the assembled were packing decades’ worth of rage at the liberal establishment into those three words.

But does anyone think for a second that Romney fils would have walked out on his party, or even worked to moderate certain platform planks? It’s beyond comprehension. We’ve seen plenty enough now to know that that isn’t who Mitt Romney is. Instead, this self-selected member of the East Coast elite opened his convention speech this way:

For decades now, the Washington sun has been rising in the east. You see, Washington has been looking to the eastern elites, to the editorial pages of the Times and the Post, and to the broadcasters from the coast.

If America really wants to change, it’s time to look for the sun in the west, ’cause it’s about to rise and shine from Arizona and Alaska!

On the evidence offered in these books, Romney seems in certain ways a fine and even rare person. He is diligent, industrious, and appears to be honest; he applies himself to problems, earnestly studying and following the lead of the data. He is a man of apparently deep personal virtue, generous with his money and time. He is very intelligent and has typically succeeded, wildly so, at nearly everything he’s done (except, interestingly, politics—he’s lost two races and won just one). Bill Bain, who in 1977 hired Romney into the venture capital and private equity firm we’ve been hearing so much about lately, had “seen something special” in Romney in their first meeting, write Michael Kranish and Scott Helman, veteran and well-regarded reporters for The Boston Globe, in The Real Romney: “All of the partners were impressed, and some were jealous. More than one partner told Bain, ‘This guy is going to be president of the United States someday.'”

But with all that, there still seems something missing in the man. Even R.B. Scott, a longtime magazine and newspaper journalist who is a fellow Mormon and former occasional Romney adviser who tried to enlist Romney’s cooperation in his book, Mitt Romney: An Inside Look at the Man and His Politics, cannot escape (and to his credit does not shy away from) pursuing certain dark corners of Romney’s character and identifying his weaker points:

His inability to empathize with common folk had long been his hoary hoodoo. His father had warned him about it. As a Mormon stake [roughly, a diocese] president, he was kind if often impatient and patronizing with members who didn’t measure up or were beneath him in rank and in intellectual and spiritual prowess. And on and on it went.

“His father had warned him…” For men like Romney, everything comes back in one way or another to father. Mitt was the “miracle baby,” the fourth child born nearly six years after the last of the other three, and named in part after J. Willard Marriott—like George, a nationally prominent and respected Mormon. He “grew up idolizing” his father, write Kranish and Helman. He walked the factory floor with him at the American Motors Corporation, which the elder Romney made profitable; he listened closely to his father’s religious and civic lectures; he wanted to become his father. His pursuit of the presidency surely has much to do with the fact that his father didn’t make it there, torpedoed by his famous comment about having been “brainwashed” about American progress in the war by generals on a visit to Vietnam.

Advertisement

George Romney didn’t back down from that remark, made to a Detroit television interviewer in 1967. He never backed down, not even to Nixon, with whom, as HUD secretary, he had numerous skirmishes. The son—unable even to view the “brainwashed” clip, Kranish and Helman write, until thirty-nine years later—seems to have decided that backing down is often a pretty good idea. Commentators have spent countless hours speculating whether Romney is “really” moderate or conservative. The answer is that he is neither, and both. The lessons he learned from watching his father fail to make it to the White House are: don’t stick to your guns; be flexible; suit the needs of the moment. And so, in order to complete his father’s unfulfilled destiny, he has decided to become his father’s opposite.

The Romney family’s history is, because of the religious question, pretty far from being a typical American success story. They were a prominent Mormon family going way back who got caught up in the intense ill will between Abraham Lincoln and Brigham Young. Lincoln signed an anti-bigamy law in 1862, aimed specifically at Young and his tribe, and Mitt Romney’s great-grandfather had been pursued by armed US marshals on bigamy charges. Miles Romney ended up in Mexico, as did many Mormons of the period, fleeing what the Church of Latter-Day Saints still thinks of as a great persecution of its people.

Miles’s son and Mitt’s grandfather, Gaskell, flourished there, at least until 1912, when during the civil war Mexican revolutionaries suspected (probably incorrectly) that these Yanqui interlopers would take up arms against them. Gaskell’s land was seized, and he became nearly penniless. He returned to the United States and, his grandson might do well to remember, got back on his feet partly because of assistance from the federal government, which had established a $100,000 relief fund for Mormons fleeing Mexico. The Romneys ended up in Salt Lake City, where Gaskell made a handsome living in home construction. George was five.

George moved to Washington, D.C., in the early 1930s. His betrothed, Lenore LaFount, whom he had met in Utah, had her eye on a Hollywood career, and even landed a few parts and seemed on her way. But the unstoppable George persuaded her to marry him. Even though he never managed to finish college, he became a lobbyist—there weren’t many in those days—for the aluminum industry. They moved later to Detroit, where he became head of the Detroit office of the Automobile Manufacturers Association, eventually overseeing the industry’s war effort. The war ended, and in March 1947, after Lenore had been told by doctors that she could not possibly get pregnant again, the miracle baby arrived.

A beautiful house in exclusive Bloomfield Hills; the Cranbrook School, a private school with a lush campus; unimagined success, as George developed the AMC Rambler, a small car that he intended as competition to the hulking beasts Detroit was producing at the time (“compact car” and “gas guzzler” are among the elder Romney’s contributions to our automotive lexicon)—this was the milieu in which Mitt Romney was raised, apparently never getting into a whit of mischief. When he was seventeen, he met Ann Davies—fifteen, beautiful, but not a Mormon—at a party. He announced straightaway his intention to marry her, and she agreed that they would do so at the right time. But first, college beckoned, and Mitt’s obligatory missionary service.

He started at Stanford in the fall of 1965. It was a comparatively conservative campus in that age when Mario Savio was rabble-rousing across the bay up in Berkeley, but even Palo Alto provided Romney with a measure of culture shock. One of the resident assistants in his dorm was David Harris, the radical activist who would later marry Joan Baez. Romney attended one antiwar rally, Scott reports, wearing “his signature blazer and tie.” But by and large, he stuck to the company of his fellow young conservatives, challenged students on the issues of the day at parties (where he did not smoke or drink), and spent many weekends secretly (even from his parents) flying back to Michigan on weekends to see Ann.

Advertisement

Next came the missionary period, and here we begin to reach the part of the biography that the newspapers have already filled in. Romney went to France, finally ending up in Paris (in 1968, no less). He was driving a car one night in the French countryside, with passengers including the Mormon mission leader in France and his wife, and it was hit headlong by an apparently drunk French priest. The mission leader’s wife was killed; Romney was pronounced dead at the scene by one jumpy gendarme, although it turned out that his injuries were comparatively minor. He was—as was his custom—the most energetic young man in the mission, although he found that after knocking on French doors to expound the Mormon faith he ended up spending more time defending Richard Nixon than winning any converts.

He returned to America, and to school—although at the more convivial Brigham Young University now, not Stanford. Ann had already enrolled, and Mitt upon his return was surprised to find that he had to bat away one competing suitor. They married while still undergraduates, which is not unusual there, and began producing the progeny that the Book of Mormon commanded of them (they have five sons, all now grown and married, who have produced sixteen children of their own). He went to Harvard, gaining acceptance to a joint MBA and law program and graduating with honors. He found a job with the Boston Consulting Group, an early business consultancy, and he and Ann bought a home in the solid suburb of Belmont, just beyond Cambridge. He ascended the corporate ladder and the religious one, rising in the local Mormon hierarchy, becoming first a bishop and eventually the president of the Boston “stake.”

It was at this point that two pivotal events occurred, one of which might be controversial for him this fall, the other of which is certain to be. The first involves his religious work. Carrel Hilton Sheldon, a local Mormon woman who already had five children, found herself pregnant again in 1983. A complication developed, and her doctor advised an abortion. This being a thorny matter religiously—the church generally disapproved, with rare exceptions—she sought the counsel of the man who was the local stake president at the time, Gordon Williams.

According to Sheldon—whom Scott interviewed exclusively for his book—Williams told her to do what the doctor advised. Romney, a local bishop at the time, got wind of this and inserted himself aggressively into her life. He badgered Sheldon and her family, accused her of lying about Williams approving an abortion, and struck Sheldon’s father as “an authoritative type of fellow who thinks he is in charge of the world.” Astonishingly, when The Boston Globe asked him about this in 1994, he gave the kind of slippery response for which he is increasingly becoming known: “I don’t have any memory of what [Sheldon] is referring to, although I certainly can’t say it could not have been me.”

The New York Times told this story, largely based on Scott’s reporting, back in October.2 It caused considerable comment at the time. Whether it returns will depend on circumstances—whether, say, Barack Obama’s campaign feels the need to push the women’s vote. The other event from that period, Romney’s decision to become the head of Bain & Company’s private equity arm, Bain Capital, is with us now and will not go away.

Bain & Company specialized in venture capital, essentially straightforward investing. Private equity—leveraged buyouts; after the LBO scandals of the 1980s, they simply changed the name—is another matter. PE firms scour the landscape for struggling companies, bid to restructure them, load them with debt in the form of borrowed bonds or notes from banks or hedge funds, and acquire them. PE firms invest very little of their own money, and they take advantage of a key tax loophole that permits them to deduct from their taxes the interest they pay on the money they’ve borrowed to finance the purchase.3 The company might swim or it might sink. It will almost certainly shed resources, which often means laying people off. The harsher the “restructuring,” in some cases, the better the PE firm stands to do. And since the profits come in the form of capital gains for the partners, they are taxed at much lower rates than income—just 15 percent as opposed to 35 percent.

Romney initially turned down Bill Bain’s offer to head the PE arm, until, Kranish and Helman report, Bain sweetened the offer with a promise that if the PE operation failed, he “would craft a cover story saying that Romney’s return to Bain & Company was needed because of his value as a consultant.” And so, in 1989, Romney started down the path that would eventually lead him to a net worth of at least (it could be more, the authors suggest) a quarter-billion dollars.

Kranish and Helman give a comprehensive reading of the Bain years—the greatest contribution of their book. They write that the “most thorough” analysis of Bain’s performance during Romney’s tenure (1989–2001) came from an analysis written by Deutsche Bank, which found that of sixty-eight major deals, nearly half—thirty-three—had lost money or merely broken even. On the others, though, profits soared, sometimes for everyone, and sometimes not. Certain success stories, like Domino’s Pizza, are widely known. On the other side of the ledger, there was a buyout of a department store chain called Sage Stores, for example. It made Bain $175 million in 1996–1997. But three years later, the company was in bankruptcy.

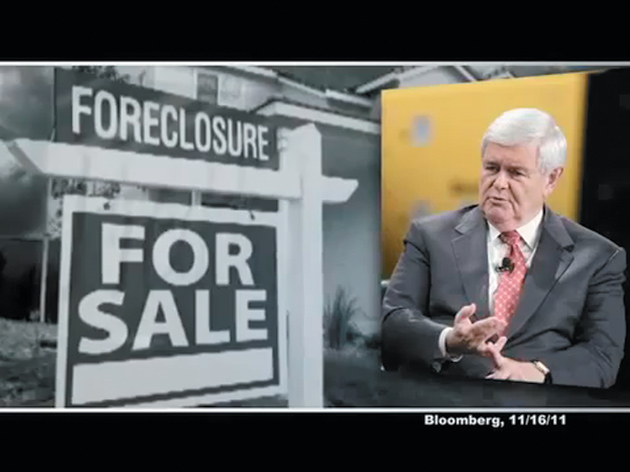

All these matters came starkly to the fore in mid-January with the release of the twenty-seven-minute film King of Bain, one of the most stunning and mysterious campaign artifacts of our time. It was made not by a liberal but by a conservative, Jason Killian Meath, who had produced ads for the Romney campaign in 2008. It was commissioned, according to Peter J. Boyer of The Daily Beast, by another conservative—Barry Bennett, who works at a firm whose principals include Dick Cheney’s daughter Mary.4 The rights were then purchased by a Super PAC affiliated with Newt Gingrich, apparently with money supplied by right-wing Las Vegas tycoon Sheldon Adelson. All this right-wing muscle has been invested in a project that makes Oliver Stone seem timid. A typical snippet of the voice-over goes:

This is a tale of greed, playing the system for a quick buck, a group of corporate raiders, led by Mitt Romney. More ruthless than Wall Street. For tens of thousands of Americans, the suffering began when Mitt Romney came to town.

The film was quickly and largely (though not wholly) discredited. Gingrich and Rick Perry, who led the attacks on Romney’s “vulture capitalism” (Perry’s phrase), were warned to cool it by Rush Limbaugh and others on the right. Romney has tried different defenses, first saying Bain created “more than 100,000” jobs, then revising that downward to “tens of thousands,” then to “thousands,” before it spiked back up in a January 16 debate to 120,000. The Obama people are presumably building their file of legitimate attacks on Bain. An argument about whether Bain created or eliminated more jobs will dissolve into the usual fog of unprovables, and it would be foolish of the Obama people to pursue that. (Still, is 120,000 jobs over twelve years really that impressive?) The point is that Bain Capital existed not to create jobs or destroy them, but to enrich the investor class—that now much-discussed “1 percent”—Romney himself very much included.

What is most interesting about the rest of Romney’s résumé—his governorship, his success at turning around the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics, and his failed political runs, against Ted Kennedy in 1994 and for president in 2008—is the way he consistently misrepresents both his triumphs and his setbacks. His one gubernatorial term was largely a success, but he now downplays for obvious reasons his most impressive achievement, the health care reform bill, and embellishes other accomplishments. On the subject of job creation, Kranish and Helman note that little of it occurred during his term: fewer than 40,000 new net jobs in his four years, or a 1 percent gain, the “fourth weakest rate of job growth of all states over the same period.” With regard to the Olympics, he did indeed straighten out some serious financial problems, put the games in the black, and oversee what is regarded as one of the most successful Olympiads of recent times. But Scott is near apoplexy over Romney’s urge to self-aggrandize and his need to exaggerate the failures of his predecessors, charging them with corruption (in his book on the subject, Turnaround) even after a judge had thrown out the charges against them.

What is striking in Scott’s account is not merely the fact of Romney’s numerous flip-flops on political issues familiar and less so (a less familiar one: the Massachusetts Romney refused to sign Grover Norquist’s anti-tax pledge in 2002, while the national Romney, in January 2007, became the first Republican presidential candidate to sign it). It’s his clumsy way of trying to assert that he has not in fact changed positions. On abortion rights, he took to saying in about 2007 that he had “always been personally pro-life” but had respected Roe v. Wade as law. But if he was always pro-life, why did he and Ann make donations for years to Planned Parenthood? And why, when asked about this, did he, in Scott’s words, “gracelessly roll his own wife under the bus” by saying, “Her contributions are for her and not for me”?

Romney appears to have a strong need to ingratiate, an urge to say much more than he really needs to say. When he wanted to prove he was a hunter and a regular guy, he made reference not to hunting animals or game but “varmints.” Twice. He boasted that his father marched with Martin Luther King Jr., but, admirable as his father was on civil rights, this was not true. His sons may have avoided military service, but they were “showing support for our nation” by…working on his campaign. The list goes on.

At other moments, a very different impulse reveals itself, and Romney’s deep and perhaps even unconscious sense of class superiority rises to the surface. He likes “being able to fire people,” he said to an audience recently, expecting a laugh that did not quite materialize. Complaints about his income are nothing more than “the bitter politics of envy.” Income inequality—this is the most incredible one to me—should be discussed only in “quiet rooms.” And his speaking fee income was “not very much” ($374,000 in the year ending in February 2011). Here again, he is his father’s opposite: George Romney was known for refusing bonuses, explaining that no executive needed to make more than his $225,000 a year ($1.4 million in today’s dollars).

Both urges, to pander awkwardly and to protect the prerogatives of his class, are at play in matters of policy. Romney’s proposed tax cut, writes The Washington Post’s Ezra Klein, is roughly three times the size of George W. Bush’s 2000 proposal. It’s far more regressive—it would actually raise taxes on many working-class people, which Bush did not do—and would add to the deficit a hefty $600 billion.5 Likewise, Jonathan Cohn of The New Republic found that Romney’s proposed budget would cut at least 14 percent and perhaps 25 percent from every domestic program—on top of the cuts already slated to go into effect as a result of the congressional deal on the debt ceiling.6

Romney has benefited from running against a weak, not to say mostly preposterous, field of competitors. Most experts felt, even after South Carolina, that he would still grind out a win in the nomination battle with Gingrich, who is unacceptable to his party’s establishment figures for so many reasons (another lucky break). And if he is the nominee, he may benefit this fall from a weak economy, in which case President Obama will have a hard time persuading many independent voters to stick with him.

Romney would certainly, if elected, prove competent to do the job. Competence isn’t the question. Competence toward what end, however, is. He seems particularly intense when he talks of the need to build up the armed forces and would be competent at that. Asked in the first of two South Carolina debates whether the US should negotiate with the Taliban to end the fighting in Afghanistan, he answered:

Of course not…. Of course you take out our enemies, wherever they are. These people declared war on us…. We go anywhere they are, and we kill them.

“There is no leader who can provide sound leadership on the basis of unsound principles.” Words spoken long ago by the father, and long since betrayed by the son.

—January 26, 2012

-

1

On the page on his website devoted to his father, a Daily News article is cited that pointedly says “both father and son walked out” of the convention. See www.aboutmittromney.com/georgeromney.htm. ↩

-

2

See Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “For Romney, a Role of Faith and Authority,” The New York Times, October 15, 2011. ↩

-

3

For a clear, detailed, and concise explanation of this loophole, see Merrill Goozner, “Private Equity’s Edge: Buy Now, Deduct Taxes Later,” The Fiscal Times, January 9, 2012. ↩

-

4

See Peter J. Boyer, “New Anti-Romney Video Attacks Bain Capital Work,” The Daily Beast, January 6, 2012. ↩

-

5

See Ezra Klein, “On Policy, Romney Is Far to Bush’s Right,” The Washington Post, January 17, 2012. ↩

-

6

See Jonathan Cohn, “Moderate Mitt? Have You Looked at His Budget?,” The New Republic, January 15, 2012. ↩