Some years ago, on a visit to one of the countries carved from the ruins of Yugoslavia, I asked a friend, a sensitive writer who had just agreed to take a government position, how he could endure serving the thug who headed the state. He looked at me. “Our murderers,” he said with a thin smile, “are better than their murderers.”

Ralph Fiennes’s new film of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus conjures up a Balkan world of jostling murderers, though it is not clear that one is better than another. The setting nominally is Rome, but a Rome imagined as a decaying Central European city, with graffiti-covered concrete buildings stretched along mean streets, hard-faced, heavily armed police struggling to keep the hungry populace from erupting into riots, and sleek politicians performing in a parliamentary charade that only half-conceals the fact that the military is the state’s sole coherent, cohesive force.

There is a good reason that the generals wield such power. Rome has enemies, foremost among them the Volscians, whom the film depicts as at once provincial and dangerous: in their headquarters the Roman generals watch grainy footage of the Volscian paramilitary leader Tullus Aufidius (Gerard Butler) interrogating and executing a Roman prisoner from whom he has ex- tracted strategic information that might prove useful for his next bloody incursion into Roman territory.

The scene of torture and execution is not in Shakespeare’s script, though the words spoken in it are. Deftly lifted by the screenwriter John Logan from a scene late in the play, they are reset near the beginning and given to different characters in order to depict the grim challenge faced by Rome and to embed that challenge within our own news cycle. The videotaped execution is one of many moments in Fiennes’s Coriolanus in which the news about which Shakespeare’s characters constantly speak—“The news is, sir, the Volsces are in arms,” “There came news from him last night,” “Yonder comes news,” “What’s the news in Rome?” “What’s the news? What’s the news?”1—is given the form that typifies our own nervous scanning of scenes of mayhem and menace.

Shakespeare’s tragedy—which he wrote late in his career, probably around 1608—readily lends itself to modernizations. In the 1930s Fascists in Germany, France, and Italy embraced the play for what they took to be its contempt for liberal democracy and its celebration of the martial heroism of a fearless leader. (The Führer Coriolanus, a school edition of the 1930s told its young readers, is trying to lead the Roman Volk to a healthier society, “as Adolf Hitler in our days wishes to lead our beloved German fatherland.”2)But the play’s depiction of the masses in revolt also made it a favorite of the Communists. In the 1950s Bertholt Brecht reworked the script in order to enhance its championing of proletarian insurgency against the contemptible lies of the generals and the corrupt politicians. (Set in 1953, Günter Grass’s 1966 play Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising sardonically imagines Brecht in East Berlin directing rehearsals of Coriolanus at the time of the popular uprising against the Communist regime.)

Fiennes’s Coriolanus distributes its contempt evenhandedly. In the text of Shakespeare’s play, the mutinous citizens, based on the starving poor who rioted for food in the English Midlands in 1607, are easily manipulated, but they have a certain dignity and rough eloquence. In the film, they are reduced for the most part to young ideologues, mouthing slogans, marching under banners, and, in one memorable moment, spitting on Coriolanus. Their political representatives, the tribunes Sicinius and Brutus, are hopeless hacks, conniving only to enhance the positions of privilege that enable them to eat in the Senate Dining Room.

The principal mouthpiece for the party of the ruling nobility, the chain-smoking Menenius Agrippa—played with such pitch-perfect accuracy by Brian Cox that one regrets the film’s deep cuts in his part—receives better treatment, but his political and moral position is fatally compromised. Dismissed with nauseated disdain by Coriolanus, Menenius quietly betakes himself to the polluted bankside and, in a silent tableau not in Shakespeare’s play, slits his wrists.

And the play’s hero, Caius Martius, called Coriolanus? When we first see him quelling the riot, Fiennes plays the part with considerable restraint. Dressed in combat fatigues, his steely, quiet voice belies the harshness of his words:

What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues,

That, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion,

Make yourselves scabs?

But he throws all restraint to the winds in the horrific battle for the Volscian town of Corioles, where his crazed, unstoppable, virtually single-handed conquest of the citadel earns him his honorific sobriquet. His shaved head covered with the blood of those he has slain, Coriolanus emerges from the ruins of the citadel as if from a monstrous womb, a nightmare of boundless violence and hatred and nihilistic nausea.

Advertisement

The nightmare is in Shakespeare’s character; Fiennes is not inventing it. But he enacts it in the spirit in which he plays Voldemort in the Harry Potter movies, that is, with an all-encompassing histrionic energy that leaves little room for nuance. Having achieved a facial expression that suggests a man at once snarling and gagging, Fiennes refuses to give it up for more than a few moments at a time during the entire remainder of the film. It is telling that the screenplay cuts the bit of dialogue in which an exhausted Coriolanus tries, though unsuccessfully, to remember the name of a poor inhabitant of Corioles who had been kind to him and has now been taken prisoner by the Romans. There is no room even for such a diminished and incomplete gesture of kindness; it leaves its trace only in the mute fact that the rampaging Coriolanus does not shoot a terrified old man who offers him a drink of water.

There are, to be sure, in Fiennes’s performance what we might call varieties of nausea. Toward his wife and young son, there is mild aversion compounded of incomprehension, indifference, and a dislike of touching or being touched. Toward politicians bent on compromise and soldiers who are less than suicidal, Fiennes displays a blend of angry impatience, distaste, and active loathing. Toward the shouting, starving masses, he feels a revulsion to which Shakespeare’s words allow him to give stupendous expression:

You common cry of curs, whose breath I hate

As reek o’th’ rotten fens, whose love I prize

As the dead carcasses of unburied men

That do corrupt my air: I banish you.

Toward Aufidius, the hated enemy in whose heart, he says, he dreams of washing his fierce hands, Coriolanus’ nausea takes on a distinctly erotic tinge. “I sin in envying his nobility,” he admits,

And were I anything but what I am,

I would wish me only he.

For his part, Aufidius returns the compliment. When Coriolanus, banished from Rome, comes alone to the Volscian camp to offer to fight against his own country, Aufidius says that every night he has

Dreamt of encounters ’twixt thyself and me—

We have been down together in my sleep,

Unbuckling helms, fisting each other’s throat—

Even though the last two lines are cut in the film, the scene, shot in the darkness, the two men breathing heavily, their faces almost touching, has a far greater sexual charge than any other, including that of Coriolanus in bed with his wife. But while Aufidius looks like he is trying to decide whether to kill or fuck the man he holds in his arms, Coriolanus looks like he is going to throw up.

Fiennes’s curled upper lip, slightly furrowed brows, and sunken eyes are the all-purpose signifiers of his response to the world. That response extends to the most complex and fraught of his relationships, that with his formidable mother, Volumnia. Performed brilliantly by Vanessa Redgrave, Volumnia makes clear her aristocratic hauteur, her zealous patriotism, her ferocious cult of martial honor, and her limitless investment in the son she has shaped to act out her fantasies. In one of the film’s best scenes, in the bathroom of the family mansion, Volumnia bandages the wounds on her son’s body, wounds in which she takes such ghastly pleasure: “I have lived/To see inherited my very wishes,” she whispers, in a fathomlessly perverse lullaby, “And the buildings of my fancy.”3 It is at this moment of deepest intimacy that she expresses the ambition that will bring everything to ruin:

Only

There’s one thing wanting, which I doubt not but

Our Rome will cast upon thee.

It is worth the price of the movie to witness the creepy way, at once possessive and possessed, that Redgrave mouths the words “Our Rome”—to which Fiennes responds with (what else?) another look of nausea.

“Our Rome” will not in fact cast the honor of the consulship on its military savior; not, that is, without the ritual of humility that custom requires and that the proud Coriolanus is unwilling and unable to give. What stands at the topmost pinnacle of the carefully calibrated poetics of disgust that constitutes his inner life is electioneering. The timing of the movie’s release in the United States could not be better: the prolonged spectacle of the Republican primaries has produced in me, for the first time in my life, some sympathy with Coriolanus’ loathing of the limitless mendacity and fraudulence of office-seeking. Campaigning for votes—“voices,” as they are termed in the play—is for him an unbearable form of self-display and self-abasement. His angry refusal, against the urgent pleas of his mother, of Menenius, and of his party, to play the game as it has to be played leads to his banishment and, ultimately, to his death.

Advertisement

But here Fiennes’s mastery of nausea reaches its limit as an interpretation of Shakespeare’s weird and difficult play. What his perennial lip-curl fails to disclose is why the story of Coriolanus, which he encountered in Plutarch’s Lives, might have fascinated Shakespeare as something more than a curious specimen of abnormal psychology. Beyond inflexible pride, martial valor, and disgust—all qualities that Fiennes is able splendidly to convey—Coriolanus’ character has a quality that Shakespeare had already begun to explore in the very different figure of Cordelia in King Lear: an adherence to principle so extreme and uncompromising that it threatens the whole social order and must in effect be eliminated if life is to go on. Of course, Cordelia, the young girl whose voice was ever “soft, gentle, and low,” is the very opposite of the brawling, bloody Roman warrior, and the social order she calls into question by refusing to conform is not a republic but a monarchy. And yet, though the viewer of Fiennes’s film would never grasp the affinity, she is Coriolanus’ secret sharer.

In the text of Shakespeare’s play, the aristocratic Coriolanus seems driven by an ideal of perfect integrity. What disgusts him about campaigning for office is the pretense that he has done whatever he has done not as a free agent but as a public servant dependent on others:

To brag unto them ‘Thus I did, and thus,’

Show them th’unaching scars, which I should hide,

As if I had received them for the hire

Of their breath only!

He cannot understand why his mother, of all people, is urging him to flatter “the mutable rank-scented” multitude for the sake of their votes. She was always accustomed to call the people

woolen vassals, things created

To buy and sell with groats, to show bare heads

In congregations, to yawn, be still and wonder….

Now she wants her son to fawn and deceive and pretend to be someone he is not.

“Would you have me/False to my nature?” he asks her, genuinely baffled; “Rather say I play/The man I am.” Volumnia answers with a taunt worthy of Lady Macbeth—“You might have been enough the man you are/With striving less to be so”—and Coriolanus tries at least briefly to play the politician. He descends to the marketplace, determined to “come home beloved/Of all the trades in Rome.” But his attempt is a disastrous failure.

Banished from Rome and embittered, he goes off “alone/Like to a lonely dragon.” Radical isolation—all ties broken, all pretense of dependency abandoned—enables him, as he imagines it, to be true to his “nature.” With reckless daring, he makes his way to the enemy Volscian camp, whose army he inspires and leads against the city that had expelled him. At the head of this army, implacably rejecting the desperate appeals for peace from his former friends and his family, he returns desperately to his dream of absolute autonomy:

I’ll never

Be such a gosling to obey instinct, but stand

As if a man were author of himself

And knew no other kin.

“As if a man were author of himself.” In the play, Coriolanus asserts this freedom from all kinship just before his mother makes her final appeal, begging him not to destroy the city where he was born. In succumbing to her appeal—collapsing under the weight of his mother’s claim upon him—he exposes himself, as he fully understands, to the murderous rage of the Volscians, who kill him. Abandoning his dream of autonomy, he abandons his life. But in the film, the words expressing this dream are cut. They are missing, along with the whole fierce, mad, fatal fantasy of integrity that for Shakespeare was at the heart of his strangest, least lovable hero. In its place Fiennes offers only his brilliant variations on the theme of nausea.

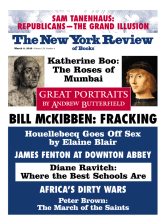

This Issue

March 8, 2012

Schools We Can Envy

Work, Not Sex, At Last

Why Not Frack?

-

1

All citations of Coriolanus are to The Norton Shakespeare, second edition, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et. al. (Norton, 2008). ↩

-

2

Martin Brunkhorst, Shakespeares ‘Coriolanus’ in deutscher Bearbeitung (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1973), p. 157. ↩

-

3

The screenplay cuts earlier lines spoken by Volumnia to Coriolanus’ wife Virgilia that make the mother’s investment in her son’s wounds even more perverse:

The breasts of Hecuba

When she did suckle Hector looked not lovelier

Than Hector’s forehead when it spit forth blood

At Grecian sword, contemning.The omission of the lines is part of a larger pattern of trimming in the interest of speeding up the action, modernizing the setting by stripping away references to the ancient gods and myths, and simplifying the play’s exceptionally knotty and complex poetry. ↩