Libraries were lending out their copies of Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians ever less frequently before Michael Holroyd brought out his groundbreakingly indiscreet biography of the Bloomsbury writer in the late 1960s. By 1974, when the first of Holroyd’s two volumes on the life of Augustus John appeared, canvases by this one-time star of London’s art world had been relegated to the storerooms of many a British museum. What hopes there might be of reviving the sprawling theatrical weltanschauung of George Bernard Shaw had been a puzzle for producers and critics for decades before Holroyd’s correspondingly vast biography of the playwright came out at the turn of the 1990s. In each of these three major projects, Holroyd looked back at figures who had seemed to tower over the cultural landscape of late-imperial Britain at the time of his own birth in 1935, but who more lately had been shelved away, to linger as little more than significant rumors.

That angle of approach gave Holroyd a free hand to make things new—to surprise himself and his audience with the unexpected discoveries of emotional life he could unearth from archives and private papers. It is his good-tempered nosiness that has secured Holroyd a large, attentive audience. As a rule he is fond of people, his urbane prose suggests, and he is disposed to respect them, but above all he longs to know more about them; and he is able to persuade us to share his longing. Seemingly, then, it was not so much the historical importance of his subjects that sold Holroyd’s biographies as sheer curiosity: his passion for the somewhat obscured, his drive to exhume and reanimate.

Before he made his name with that life of Strachey, Holroyd had devoted his first publication to a “quite hopelessly neglected”1 English man of letters named Hugh Kingsmill. Thirty-five years later, the by now celebrated biographer could afford to investigate persons of yet slenderer public significance, namely his own grand- parents and parents. Basil Street Blues (1999), reapproaching late-imperial Britain through lives passed in precarious gentility and concealed despair, masterfully extended his scope as a writer.

Halfway through its narrative a new character shuffled into view—the author himself as a youth. The success of the book spawned a sequel, Mosaic (2004), and in parts of that professedly “wayward” family history, this figure got inspected in greater detail. Holroyd explained how a fellow writer’s take on Basil Street Blues had struck home: “You stay hidden.”2 She had been left wanting to know more about how his own emotional life had taken shape. “I do not know the answers to these questions,” he continued, “and feel a great reluctance to answering them. But other readers, too, have chided me.” It was not only his readers, perhaps, that prompted him to offer up a memoir of a former romance and some words about his marriage to the novelist Margaret Drabble. It was the sense that he was involved in art, and that art is bound up with self-revelation. For if in his hands biography could operate independently of the subject’s historical significance, then biography must be something other than a craft, a mere jewel-setting of archival resources. Even high art, however, has its formal constraints: What internal logic does his form of writing possess?

A Book of Secrets, Holroyd’s new publication, is, like Mosaic, an experimental construction. (In fact Holroyd used just the same kind of phrasing to explain what he was attempting in Mosaic.3) Curiosity rules, roving where it will among assorted lives from his favored historical era. Let the stabilizing principle be the author himself. But this figure, with his already proclaimed “great reluctance” to plunge into self-analysis, remains little more than a two-dimensional frontman, an amenable cipher. In the opening pages we glimpse him as a bachelor researcher with his eye on some girl working in a museum. But that’s just a decoy: he gets diverted by a portrait bust in the museum galleries, and as his research into its origins deepens, the first-person narrator drops almost out of sight. He reappears ninety pages later as a seventy-year-old smiling public man helping another septuagenarian research her family history, a quest that takes him to the sunny Gulf of Salerno, south of Naples.

Here Holroyd lunches with another celebrity, Gore Vidal. He lets us know how he tries to amuse Vidal by quipping that a third celebrity, Salman Rushdie, is his “foul-weather-friend.” He blithely adds how his traveling companion hailed his “sparkling form” at the dinner table, and how later, when he impersonated Strachey at a literary festival, everyone roared with laughter—“I had got away with it.” Presumably writing with his travel journals to hand, he tells us what he had for breakfast and how he read the road map wrong—but absolutely nothing of interest about himself. The blandness is impenetrable: if this is a book of secrets, they won’t be his.

Advertisement

If by temperament Holroyd is not the man to compose a book of intimate confessions, perhaps he can instead turn his text around some physical location. In his preface he points to the Villa Cimbrone, the house that he visits when in Italy, as the crossroads where the various life stories that interest him more or less meet. This shimmering palazzo hangs high on a mountain overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. Its terraces with their belvederes, their pergolas, their azaleas, and their junipers transport the visitor, so Holroyd intimates, into a paradisal dream. This dream may be all the headier if the visitor is aware that literary luminaries such as D.H. Lawrence and Vita Sackville-West have been transported there before him; but that consideration may also narrow his options. It is hard by this stage for a writer to find fresh ways to evoke the pleasures of Mediterranean light and air, and Holroyd does not very seriously try. For an extended description of the place he refers the reader to a letter written in the 1930s by Achsah Brewster, an American friend of Lawrence’s. After all, Holroyd’s own forte is people.

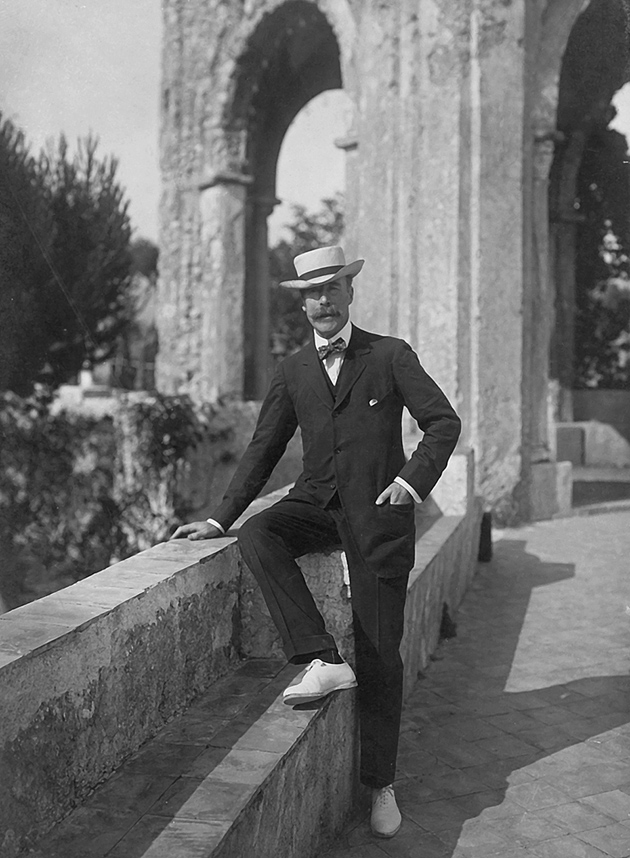

His book, it turns out, revolves around three main life stories—those of Ernest Beckett, Violet Trefusis, and Eve Fairfax. Ernest Beckett became the owner of Cimbrone in 1905, at the age of forty-nine, and it was his funds that transformed the site into the pleasure palace that it remains. This money came from a family banking business in the North of England. The Becketts of Leeds had secured themselves a baronetcy in 1813 and had represented various Yorkshire constituencies for the Conservative Party. Young Ernest, Eton-educated, handlebar-mustached, and eminently presentable, was duly elected as MP for Whitby in 1885. But the man who plumped for a Mediterranean fantasy life twenty years later, having recently inherited the family title, had nothing to boast of from his time in politics.

After siding with Randolph Churchill (the father of Winston), the loser in a Tory party cabal, he had chosen to serve his constituents by departing on an eight-month tour of the Empire and the Far East; but his observations about “the over-education of the natives” in India, like his bluff speechifying about the dangers of Irish Home Rule, made no discernible impact on government policy. In fact this diversionary move obeyed a pattern that played out the length of Ernest’s life. He could always afford to evade.

Holroyd presents Beckett as a quite deliciously dislikable character—a Hollywood Brit villain, a Monty Python pompous buffoon. But if I say dislikable, I expect I just mean enviable. It is not simply that this scion of empire has prodigious funds to splurge on travel and art collecting. He gets all the girls. His main function on the page is to hook together a succession of desirable ladies by the force of some erotic magnetism that is never quite explained but that nonetheless quickens the pulse of the narrative. Before reaching Parliament Ernest has married Luie, a thoughtful and “athletically built” young American touring Europe on a bursary from her protector J. Pierpont Morgan: Holroyd warms to the girl and transcribes her teenage diaries.

But even before Luie has died giving birth to the third of his children five years later, Ernest has switched his interests to the “voluptuous,” reckless, and vivacious Josephine Brink. This “José” comes from South Africa to London in 1886 determined to take the town by storm: she gets presented to Queen Victoria, lets Ernest seduce her in a private suite at the Savoy, goes on to mount the boards, appearing in Oscar Wilde productions, and shows yet greater gifts for melodrama, tying up Holroyd in the chaos of her three-way love affairs.

Recoiling from this blonde bombshell, Ernest falls in with the consummately discreet Mrs. Alice Keppel, who presents her husband with Ernest’s daughter in 1894: though this, Holroyd notes, inevitably seems with hindsight a mere “rehearsal” for Mrs. Keppel’s subsequent role as mistress to King Edward VII. The “ageing playboy” then gravitates toward the “serene” but faintly melancholy English beauty of Eve Fairfax, thereby providing Holroyd with a bridge to another main wing of his enterprise. But after Eve has accepted his marriage proposal, Ernest drifts away from her too. Exasperated by England’s political system, he is lashing out against it—the drift of his accusation, Holroyd amusingly infers, being that “there might have been less trouble with women in his life…had he been given political advancement and his time and energy properly employed.” And for all Ernest’s assets, there are creditors he is keen to avoid. He heads south to Cimbrone.

Advertisement

It is dramatically satisfying that the sideways motion of this pampered wretch continues all the way to death’s door. Instead of expiring as he had hoped in the radiance of his Italian paradise, he contracts tuberculosis on a visit home in 1917 and fizzles out, aged sixty, in a Scottish sanatorium. But Holroyd’s brief life is morally edifying also, on a modest level. It does not actually seek out pat responses of the kind I’ve just expressed. It complicates the issue, patiently reminding the reader that this “dilettante, philanderer, gambler and opportunist” was also a “vivid and observant” travel writer; that after his own fashion, he was “not insincere” in his affections; and that one of his daughters, Luie’s child Lucille, would come to revere his memory.

Not she but Violet, Ernest’s daughter by Alice Keppel, carries the narrative in the book’s second half. A photograph of the twenty-five-year-old Violet taken in 1919, on the day she was wedded to Denys Trefusis, shines out among the volume’s few illustrations, her eyes brimming with a canny and captivating pathos. “The wide sensual mouth of a Rowlandson whore”: that is Holroyd quoting Cyril Connolly, a writer who knew Violet—and I note that Holroyd’s own phrasings are never quite that reckless, or yet that arresting.

The youthful Violet is hot property, in all senses. Long before she becomes a published novelist, she writes her letters with flamethrowers: “I want you. I want you hungrily, frenziedly, passionately. I am starving for you.” And then: “My life—what is left of it—is just one raw, limitless bitterness…. I am flooded by an agony of physical longing for you.” And at last: “My God, Mitya, if I could kill you I would.” “Mitya” was her lover Vita Sackville-West: these are the textual traces of a romance that scandalized upper-class England around the end of World War I, searing both Vita’s husband, Harold Nicolson (“Damn! Damn! Damn! Violet. How I loathe her”), and the hapless Horse Guards officer Denys, who until he married had never heard of lesbianism.

The story becomes an out-of-control firework that ends up burning the author. After tracking the intense and irresoluble twistings of this love-and-hate quadrangle—Violet, Vita, Harold, and Denys—for many pages, Holroyd turns from the ongoing action to speak to the camera: “And at this point, reader, I throw up my hands in despair at any of these characters behaving with proper consideration for their biographers.” Now this gambit only partly gains my sympathy. It is you who wanted to tell this story, Mr. Holroyd; no one demanded it of you. You proclaim that this book is an artistic improvisation, rather than a dutiful act of craftsmanship, by the cavalier way you select and present your data. For instance, Alice Keppel, the sole figure linking Ernest and Violet, is one of the many dramatis personae to whom we never get properly introduced, while the portraits you paint of your two dedicatees—your traveling companion Catherine Till and the Violet Trefusis specialist Tiziana Masucci—are determinedly flat and nonillusionistic.

Yes, there are good reasons for each of these tactics. Holroyd respects his dedicatees and they are alive, whereas Mrs. Keppel, famed king’s mistress, is already entirely a creature of other people’s texts. But that proves to be the problem overall when Holroyd chooses to write about Violet. This hot property has already been spoken for many times, for there is no spicier episode than her romance in the whole haut-bourgeois soap opera we loosely label Bloomsbury. Holroyd turns from Violet’s days as a catch on the lesbian scene to offer an extended review of the seven novels she went on to write—wayward and waspish inventions of some distinction, it would seem—submitting this reassessment as his fresh contribution to an established field of study. But if A Book of Secrets is some form of work of art, this is a peculiarly distancing way to proceed with it. It’s like asking your audience to take their eyes off a wide-screen thriller and instead scroll through little iPhone images of unfamiliar tourist destinations.

In fact the gesture that stakes out this book’s most distinctive terrain comes after Violet, aged fifty-two, more or less abandons her typewriter. “But,” Holroyd goes on to announce, “she had another twenty-five years to get through.” That’s a grim phrasing. Just how grim is spelled out as he homes in on the acquisitive, tyrannical, and capricious old dame, shuttled by chauffeur between Paris and Florence, who eventually starves herself to death in 1972.

And here Violet’s story becomes an envoi to that of Eve Fairfax, the one-time fiancée of her father. It was Eve’s portrait bust by Rodin in a museum that first drew Holroyd into his quest to unravel these lives. Ernest had commissioned it from the sculptor in 1905. Visiting Paris repeatedly for sittings, the young, country-bred horsewoman became friends with the elderly Parisian grandee, and for years they corresponded tenderly. Friends, but never lovers: so what became of her, Holroyd naturally wonders, after Ernest went his way? With her good looks went a ready and dismissive wit. The Duke of Grafton begged her to accept his hand not for his money, but for himself. “Rather a tall order,” she replied.

A wit reapplied to herself, many decades later: “Those whom the gods love die young, and I am eighty-seven.” Nothing much—seemingly—had happened. Eve’s existence, passed quietly and alone among English county gentry, proves virtually a nonlife in normal narrative terms, and moreover giddyingly vast: she would only depart it in 1978, at the age of 106. I think that Holroyd’s attention to it stands at the heart of his project, and it is what I take away most vividly from reading him.

When Eve was thirty-seven, a county friend gave her a large, leather-bound, empty volume. It might have been meant for a diary, but in Eve’s hands it became “partly a social calendar, partly a volume of autographs, partly an eclectic anthology…an omnium gatherum, a vast vade mecum, following no order and having no chronology, theme, agenda, prescription.” Holroyd writes with this tome in his own hands, on his own desk. It has come to obsess him. He quotes extensively from the poems inscribed in it by the hosts between whom Eve circulated (for she herself subsisted in genteel near indigence) and by fellow hangers-on—literati, artists, musicians. “Monstrous and forbidding,” he dubs the object thereby accumulated:

Though the pages blew from it like leaves from a tree, it increased in bulk and irregularity as she stuffed into it all sorts of photographs, letters, bits and pieces. So it began to resemble a huge and dilapidated saddle of a horse, a chaotic artefact that was a part of Eve’s personality: her pride and her penance. Like an extraordinary tramp, she travelled the country between Castles, Halls, Granges, Manors, Priories, Abbeys weighed down by its heavy load like a figure from The Pilgrim’s Progress.

In summary, Holroyd writes, Eve’s book, “with its great empty spaces, its undergrowth of clichés, its photo parade of men and women on horses, of children and flowers, dogs, prime ministers, and then the dark floating passages of poetry, is truly her autobiography.”

There is a book by Holroyd I am holding in my own hands, and its contents seem fathomlessly random. Here we read about a mustachioed Briton being greeted with a nineteen-gun salute by the Khan of Kalat, there about an American teenager longing to escape the “horrid little out of the way place” that is 1880s West Point. At one point I find myself skimming the journals of a self-satisfied literary celebrity, and at another I am captivated by a ludicrous naval incident off the coast of Sardinia in 1908, when the German Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz has to be rescued from a steamship run aground.

For all the urbanity of Holroyd’s drafting, it is hard to convey what a peculiarly uneven ride his Book of Secrets presents: “picaresque” would be too polite. But he unmistakably analogizes this experiment in life writing with that gap-strewn omnium-gatherum when, in his epilogue—itself insistently nodding toward the finale of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu—he remarks that “of necessity,” his tale of Ernest, Violet, and Eve contains “many empty spaces marking what has been hidden or forgotten, lost or misunderstood—mysterious spaces, which have themselves become part of a recurring pattern in this recreation of their lives.”

There’s a grimness here, too. Lives and stories don’t track each other that well, what with all these lacunae in the latter, all that hideous superfluity of time “to get through” in the former. Maybe the unappealing secret is that the more you try to narrate life, the more you hit a blank. Is that why Holroyd announces in his concluding paragraph that he will write no more books? Or are there more productive secrets that might drive a writer back to his keyboard?

I note the moment when, poring through Eve’s forbidding “autobiography,” Holroyd uncovers among its pages a solitary allusion to a vanished son to whom she covertly gave birth in 1916. “So…this is a book of secrets,” he is moved to affirm. (Since A Book of Secrets itself was published, Holroyd has uncovered more about this son, as he has revealed in a recent article for The Guardian.4) Maybe his final bow is merely in the manner of one of Frank Sinatra’s innumerable “farewell tours.” Curiosity might get the better of art.

This Issue

March 8, 2012

Schools We Can Envy

Work, Not Sex, At Last

Why Not Frack?

-

1

This description, which comes in a letter to Holroyd from his friend William Gerhardie, is quoted in Basil Street Blues (Little, Brown, 1999), p. 273. ↩

-

2

Mosaic (Little, Brown), p. 85 (quoting a letter from the novelist and memoirist Margaret Forster). ↩

-

3

“This is a book of surprises…. Beginning as a requiem, it evolved into a love story, then a detective story, finally a book of secrets revealed.” Preface to Mosaic, p. 1. ↩

-

4

Michael Holroyd, “Family Secrets,” The Guardian, October 28, 2011. ↩