The Republican presidential nomination contest, which has entered a lull before it presses toward a probable showdown in March and April, when thirty primaries and caucuses will be held, has found its script. It will be a struggle between the “establishment” candidate and one or another “insurgent.” What might seem confusing is how, and on whom, these labels have been affixed. According to the accepted calculus, the establishment candidate is Mitt Romney, although as many have pointed out, he is less a creature of Washington than any of his three remaining rivals.

Romney has held elective office only once, his single term as governor of Massachusetts (2003–2007), and spent most of his professional life, as he tirelessly reiterates, in the “private sector.” The vast fortune he accumulated, including the $45 million in earnings in 2010–2011 that he reported in late January,1 on tax returns he reluctantly disclosed under pressure from his chief rival, Newt Gingrich, came in the field of private equity, “a prime legacy of the Reagan years” that remain a golden age for conservatives, as a Wall Street Journal columnist pointed out,2 but has nonetheless kept him under continual, and surprising, populist attack from the right.

This emerged most forcefully in the South Carolina primary. Gingrich’s victory there catapulted him to his current position as a lead spoiler and self-appointed outsider. Yet he too seems miscast. Though he has insisted that his is “a campaign of people power versus money power,”3 he had reported income of $3.16 million in 2010,4 almost all of it earned via politically related business, the outgrowth of his twenty years in the House of Representatives, a period marked by controversy and during which he was punished for ethics violations. Since leaving the House, Gingrich has feasted at the K Street lobbying trough and perpetuated his long, cozy association with the government-supported mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Announcing a housing partnership in Atlanta in 1995, for example, he held up Fannie Mae as “an excellent example of a former government institution fulfilling its mandate while functioning in the market economy.”

Gingrich’s ties to Freddie Mac were even stronger. The corporation paid him $25,000 a month as a consultant shortly after he too joined the “private sector” in 1999. Today, of course, Gingrich has added his voice to the chorus calling for the dismantling of both companies.5 Meanwhile, as he continues to taunt Romney, who as governor introduced a forerunner of “Obamacare,” with the epithet “Massachusetts moderate,” in tones Republicans once reserved for denouncing “Radic libs” and “left liberals,” Gingrich has had to explain his own complicity in “big-government” schemes, including his support, as recently as 2009, for cap-and-trade legislation.

The other candidates’ résumés are equally smudged. Rick Santorum, a former Gingrich ally6 who has drawn support from evangelical “social conservatives” uncomfortable with Romney’s Mormonism—and recently has had considerable success in attracting that constituency—is also a Washington insider, indeed “the Senate’s point man on K Street,” deeply involved in plans for filling lobbying firms with Republicans. Following the election of George W. Bush, Santorum held weekly meetings with lobbyists, at which, Nicholas Confessore reported in 2003, they would “pass around a list of the jobs available and discuss whom to support. Santorum’s responsibility [was] to make sure each one [was] filled by a loyal Republican—a senator’s chief of staff, for instance, or a top White House aide, or another lobbyist whose reliability has been demonstrated.”7

This collusion led to the Medicare prescription drug bill of 2003, a $500 billion program that was the capstone of the Bush-era “big-government conservatism” that is so much in disfavor on the right today. At the same time Santorum, who rose to become the third-ranking Senate Republican, was an eager pursuer of “earmarks” totaling as much as $1 billion for his constituents in western Pennsylvania.8

Only the purist libertarian Ron Paul has charted a consistent course in his twelve terms in Congress, though his dogma of “liberty” is tinged with paranoia about conspiracy, including luridly anti-Semitic and racist commentary printed under his name in a newsletter9—later withdrawn, but not altogether surprising for one who in 2008 delivered the keynote address at the John Birch Society’s fiftieth anniversary gala, held in Appleton, Wisconsin, the hometown of Joseph McCarthy.

The notably weak field and the volatility of primary and caucus voters (Santorum won in Iowa, Romney in New Hampshire, Gingrich in South Carolina, Romney again in Florida and then in the Nevada caucus, Santorum again in Minnesota, Colorado, and Missouri) have dismayed GOP leaders and conservative commentators. Some now openly speculate whether the election will be lost, when a few months ago the large gains in the 2010 elections, followed by aggressive and repeatedly successful showdowns with President Obama, seemed to point toward triumph in 2012.

Advertisement

Some top Republicans (including Senator John McCain and New Jersey Governor Chris Christie) have been pleading with primary voters to fall in line behind Romney, seen as the only electable candidate, while journalists like William Kristol fancifully pine for a late-entering white knight—Christie, Jeb Bush, or Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels—who will charge in and unite the party’s hostile factions, gathering in himself its many diffuse energies and directing them against Obama.

What makes this spectacle all the more anomalous, and possibly self- destructive, is the assumption, shared if not acknowledged by one and all, that once the primaries end, the winner—or survivor—will need to pivot sharply to the center and make an appeal to the centrists and independents who, even in this ideologically supercharged climate, will decide the election. This is a familiar ritual, enacted by both major parties. And most voters, who begin to think seriously about their choices shortly before Election Day, pay little attention to intraparty squabbling. But this year’s competition has taken place on the public stage for many months already. There have already been more than twenty televised debates; some have attracted substantial audiences, much larger than in 2008.10

Those debates have been unrelievedly strident. Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, and Rick Perry have left the stage; but they imparted a Jacobin tone that has scarcely been muted. And there is no question that the GOP’s positions have shifted far to the right. The clearest evidence is the elevation of Paul—who would abolish the Federal Reserve and revive the gold standard—from fringe figure in 2008 to respected and feared presence in 2012, and with good reason: he finished first in the influential Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) straw poll in both 2010 and 2011; in the second he easily outdistanced Romney, Gingrich, and Santorum.

This, in turn, points to the larger problem for the GOP. Its leading figures, in office and in the media, continue to espouse an antigovernment ideology that in reality attracts very few voters, even on the right. More accurately, today’s self-identified conservatives embrace movement rhetoric but not movement ideology—at least not when it is cast as policy. In The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism, Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson, Harvard scholars who have interviewed adherents of the new insurgency in different regions of the country, report that

fully 83% of South Dakota Tea Party supporters said they would prefer to “leave alone” or “increase” Social Security benefits, while 78% opposed cuts to Medicare prescription drug coverage, and 79% opposed cuts in Medicare payments to physicians and hospitals…. 56% of the Tea Party supporters surveyed did express support for “raising income taxes by 5% for everyone whose income is over a million dollars a year.”

These views, which are aligned with those of moderate Republicans and Democrats, corroborate the findings in a 2010 New York Times poll of Tea Partiers, which concluded: “Despite their push for smaller government, they think that Social Security and Medicare are worth the cost to taxpayers.”11 Such opinions reflect those of the broader public, and as much as two thirds of that public favors in principle much of Obama’s program, including his plan to increases taxes on the wealthy12—an idea derided on the right as “class warfare.” Meanwhile approval for the Tea Party–aligned House of Representatives has sunk to historic depths.13

Nonetheless, insurgent fevers run high, and Skocpol and Williamson estimate that “strong” Tea Party supporters “amount to about one-fifth of voting-age adults, or roughly 46 million Americans.” Many belong to the demographic group most likely to vote at election time, including in off-year congressional elections and in primaries when many others don’t bother. This is what happened in 2010. Only 40 percent of the eligible total voted, but those who did “were markedly older, whiter, and more comfortable economically than those who stayed home.”

Unsurprisingly, all four candidates are openly courting this faction—or factions. The term “Tea Party” is itself a misnomer. There is no single party. Instead there are many independent organizations, “about 1000 groups spread across all fifty states,” Skocpol and Williamson estimate. “Some local Tea Parties are very large, with online memberships of 1000 people or more. But most local Tea Parties have much smaller contact lists, and the typical local meeting has a few dozen people in attendance.” The authors put the national total of “very active grassroots participants” at 200,000—a tiny fraction of those said to be “strong” supporters and less than a third of a single average-sized congressional district.

It is, in other words, not a mass movement at all, and it appears to be losing steam. Even in congressional districts in which Tea Party–backed candidates won in 2010, enthusiasm has waned. A New York Times poll of voters in those districts found that “27 percent said they disagreed with the Tea Party and 20 percent said they agreed—a reversal from a year ago, when 27 percent agreed and 22 percent disagreed.”14 But the insurgent message still has an effect. Two thirds of Florida primary voters said they sympathized with the Tea Party. And Romney’s success with them—he ran slightly ahead of Gingrich—was perhaps the first indication that he is solidly entrenched as the front-runner. Certainly he has courted the GOP base. Writing in The Washington Post after the Florida results came in, Skocpol pointed out that Romney has waged a campaign as “the stealth Tea Party candidate” and has “repeatedly pledged fealty to key tea party priorities: cracking down on illegal immigration, repealing ‘Obamacare.’”15

Advertisement

Some liken this year’s election to a prior insurgency—Barry Goldwater’s campaign in 1964. At the time his program was described by the journalist Karl Meyer as representing “a mood, not an ideology.”16 But Goldwater’s intellectual champions, who included William F. Buckley Jr., James Burnham, and Milton Friedman, made concrete policy proposals (e.g., the introduction of a “negative income tax”). The 2012 campaign has been remarkably innocent of such thinking, apart from sweeping promises to roll back “Obamacare,” empower “free enterprise,” and slash taxes (while being careful to spare the costly “insurance” programs, Social Security and Medicare, that in fact place the greatest strain on the federal budget).

With one exception, Skocpol and Williamson write, “not a single grassroots Tea Party supporter we encountered argued for privatization of Social Security or Medicare,” pet projects of a conservative legislator like Paul Ryan and of organizations like FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity. The Republican aspirants have adapted to these internal contradictions. They attack Obama for increasing government spending and at the same time for trimming $500 billion from Medicare.

The impracticality of this war against government, which in fact offers no serious plan to scale government back, suggests that the conservative populism of our moment is rooted not in a coherent worldview so much as in a “mood” or atmosphere of generalized, undifferentiated protest. This is why Gingrich’s actual record, in and out of office, has mattered less to the Republican base than his skill at channeling the passions of the moment and his attunement to the idiom of grievance. While Romney, who seems to lack an authentic, individual voice, is always reciting standard texts, whether the lyrics of “America the Beautiful” or the warning that Obama is “building a European-style welfare state,”17 Gingrich has shown a gift for the original, crowd-stirring punch line: Obama is “the best food-stamp president in American history”18 as well as “the most radical president in American history.”19 He stirred the crowd even more when he scolded moderators at the two televised debates in South Carolina, touching on themes he repeated in his victory remarks when, as Politico reported, “he chastised elites, elite media or just the media seven times; Saul Alinsky, four; religious bigots, three; food stamps, three; and added pokes at San Francisco, socialism and bowing to Saudi kings for good measure.”20

This is the sort of script Romney seems incapable of mastering. In a roomful of true believers he is the interloper who mechanically moves his lips in synch with the rest but doesn’t seem to feel the emotional rhythm of the message. But his awkward style is only part of the problem. There is a more serious one, too. His recalibrations move in the wrong direction. Authentic tribunes of the right, like Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, were credentialed ideologues who were forgiven their many accommodations to the mainstream. Romney, by contrast, is the natural pragmatist seeking (for the second time; he tried it also in 2008) to recast himself as a radical, even though he knows the epithet “moderate” will eventually work to his advantage in the general election.

Richard Hofstadter, an early astute observer of modern right-wing passions, gave such a position the name “pseudo-conservatism” in 1955 and asked, “Why do the pseudo-conservatives express such a persistent fear and suspicion of their own government?” He was writing during the period when Joseph McCarthy gave the Republican Party its first contemporary flavor of insurgent populism. Hofstadter located this “dynamic of dissent” in the murky realm of “political culture,” with its pulsing “undercurrent of provincial resentments, popular and ‘democratic’ rebelliousness and suspiciousness, and nativism.”21

He emphasized these cultural matters because the mid-1950s were among the prosperous years in American history; the economy grew at rates equivalent to China’s today. This is no longer the case, obviously enough. And yet the attitudes Hofstadter recorded are still with us and attached, often, to the same emotions—nostalgia for an earlier, better America, unthreatened by ethnic diversity or by the rise of educated “technocrats.” In their interviews, Skocpol and Williamson note,

Tea Party members rarely stressed economic concerns to us—and they never blamed business or the superrich for America’s troubles. The nightmare of societal decline is usually painted in cultural hues, and the villains in the picture are freeloading social groups, liberal politicians, bossy professionals, big government, and the mainstream media.

Illegal immigration is a particular anxiety—not because employers give low-wage jobs to illegals or outsource them to China and India, but because those who slip over the border, or their children, crowd schools and hospitals. They are the “undeserving,” who drain the federal treasury and imperil the benefits due to birthright citizens.

All this exists at a remove from the arguments made by champions of the Tea Party, such as Elizabeth Price Foley in her book The Tea Party: Three Principles. Foley, a professor of constitutional law, describes a movement driven by “constitutional principles.” These include “limited government, US sovereignty and constitutional originalism.” She adds that these principles are distinct from the “‘social conservatism’ that has dominated the conservative movement for the last thirty years” and that Tea Partiers are at best lukewarm in their attitudes toward issues like “abortion” or “gay marriage.”

Foley’s brand of constitutional ideas, in turn, derives from long-standing doctrine on the right—for instance, the theories of the political scientist Willmoore Kendall, who in the 1960s, prefiguring the “constitutional conservatives” of today, wrote lengthily on the importance of the nation’s founding creedal documents, dating from the Mayflower Compact. Kendall argued that the expanding powers of the federal government

moved away from the unique and defining principles and practices central to the political tradition of our Founding Fathers, those associated with self-government by a virtuous people deliberating under God. In their place…we have embraced a new, largely contrived “tradition” derived from the language of the Declaration of Independence with “equality” and “rights” at its center.22

For Kendall the original heretic was Lincoln, who prepared the way for the later trespasses of the New Deal and the Great Society. Echoes of this argument can also be found among current followers of Leo Strauss, particularly those connected with the Claremont Institute, in California, who for nearly forty years have identified Woodrow Wilson as the author of an intrusive and even predatory “administrative state.”23

This idea has filtered into more popular venues, for instance the broadcasts of Glenn Beck and some Tea Party dogma.24 In their book Tea Party Patriots: The Second American Revolution, Mark Meckler and Jenny Beth Martin, cofounders of the Tea Party Patriots, Inc., one of the largest of the insurgent organizations, inveigh against the evils introduced in 1913, when the federal income tax began, and “the Seventeenth Amendment to the US Constitution,” providing for direct election of senators, “was ratified, forever tipping the balance of power toward Washington, and leading to a hundred-year march toward federal tyranny.”

The early accounts of the Tea Party phenomenon often depicted its adherents as apolitical citizens disturbed by the recession and mounting debt and roused from their apathy to do something about it. This may be true of some, but others are seasoned activists long involved in politics. This is certainly the case with organizers like Dick Armey, the former House majority leader who heads FreedomWorks, a 2004 offshoot of an organization set up in 1984 by the billionaire Koch brothers. Jenny Beth Martin affects a pose of naiveté in her book: “If someone had told me [in 2009] that I would soon be writing a book about American politics, I would have laughed,” she writes. But only a few pages later, when recounting her expert use of “Facebook, Twitter, and other social media,” Martin explains that “I already had a political network, having been involved at the local and state level for many years”—and since the early 2000s she was “a full-time blogger and Republican activist.” So too with the lower-profile Tea Partiers interviewed by Skocpol and Williamson: “An extraordinary number dated their first political experiences to the 1964 Goldwater campaign.”

Did ideological conservatism inspire primary voters in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, or Florida? Probably not, if Skocpol and Williamson’s findings can be believed. The picture they give is closer to Hofstadter’s account of provincial resentments, suspicion, and nativism, and highlights what might be termed the cultural contradictions of modern-day conservatism—contradictions that allow politicians like Gingrich and Santorum to present themselves as struggling outsiders or that obligate Romney to disown his one true accomplishment, the innovative Massachusetts health care program that was a blueprint for Obama’s, although its centerpiece, the “individual mandate” requiring that people have health insurance, is an idea once favored by conservative policy experts, including some at the Heritage Foundation, who saw it not as a predatory big-government scheme but as a useful compromise between government and market forces.

The strength of the conservative movement in our time begins with successful efforts at harnessing energetic factions within the GOP, sufficiently well organized at times to dictate the party’s policies and platforms and on rare occasion to achieve national victories. But it has bred internal conflict. The spectacle of the self-proclaimed anti-politician, favored by the Republican establishment, locked in combat with a putative outsider who is in fact a career politician has been a staple of GOP politics since 1940, when Wendell Willkie, “the barefoot boy from Wall Street,” a former Democrat with almost no experience in politics, wrested the nomination from the Senate stalwarts Robert A. Taft and Arthur Vandenberg. The issue then was World War II, and whether America should enter. Taft and Vandenberg, true to their “old guard” midwestern roots, were isolationists. Willkie was an interventionist, and “the only man the Republicans have who stands a chance of making an effective case” for mobilizing US industries for wartime—so a Time columnist wrote a week before the Republican convention.25

Thus was the pattern set, with favorite sons of the heartland such as Taft pitted against and usually losing to one proto-Romney or another, each an ideologically suspect moderate who commanded no particular loyalty among the GOP base but was deemed electable by of a cabal of “secret” and “highly placed New York kingmakers,”26 to quote A Choice Not an Echo, Phyllis Schlafly’s self-published tract. Some 1.6 million copies of it were printed in May and June 1964, amid Barry Goldwater’s insurgent campaign against patrician moderates. Goldwater lost major primaries to each, most humiliatingly in New Hampshire, where he was thrashed by the write-in candidate Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. Goldwater staggered through on the strength of delegates collected in uncontested primaries, and then by edging out Nelson Rockefeller in California. He then overcame a third East Coast moderate, William Scranton, who made a belated futile charge of the kind some members of today’s establishment envision Jeb Bush or Mitch Daniels making. But LBJ carried forty-four states and beat Goldwater by 61.1 to 38.5 percent.

In between Willkie and Goldwater came Thomas Dewey, the New York governor and early exemplar of compassionate conservatism unloved by the old guard, and Dwight Eisenhower, so blank a slate ideologically that the Democratic Party had courted him too, as a successor to Harry Truman in 1952.

“Bob Taft was clearly robbed of the Republican nomination, primarily because the public [was]…persuaded that Taft could not win if nominated,” William F. Buckley wrote in 1954, in a letter sent to potential backers of National Review,27 a magazine founded in part to “read Dwight Eisenhower out of the conservative movement”28 and to restore the GOP to pre–New Deal purity.

In later battles Ronald Reagan challenged the moderate incumbent Gerald Ford in 1976, and Patrick Buchanan took on the ideologically suspect George H.W. Bush in 1992. Then there was the “Republican Revolution” led by Newt Gingrich, who, in revolt against moderates within his own party, orchestrated a national campaign in 1994 that resulted in the first Republican House majority since 1954, with Gingrich giddily installed as speaker. He briefly seemed the most powerful figure in American politics, a self-infatuated lecturing presence who eclipsed Clinton himself. But this insurgency too decomposed—amid the impeachment proceedings recklessly brought against Clinton. In 1998, a lackluster showing in the congressional elections prompted a fresh epicycle of revolt led by Dick Armey. It faded when Gingrich had to resign both his speakership and his House seat. He has not since held elective office—a circumstance that makes his current ambitions all the more improbable and also fitting for this complicated moment.

These episodes have all served to replenish a right-wing movement that for the past sixty years has been the vehicle of the only sustained radicalism in American politics, but has for most of that time enjoyed only narrow popular support. Conservatives point, as if by conditioned reflex, to the glories of the Reagan years, and celebrate him as a beloved leader whose message reached across traditional party boundaries.

But this ignores the many calculations he made. Reagan abandoned long-held dogmas (opposition to both Social Security and Medicare) and changed his positions on abortion (quite as Romney as done). Once in office he continually disappointed various constituencies, including the Christian right and neoconservatives. Assessing Reagan’s first term, Nathan Glazer concluded:

Reagan was neither the Goldwater of 1964, nor the Reagan of earlier campaigns, and his victory was that of a conservatism that accepted the major lineaments of the welfare state.

He left office, some forget, with a vastly increased budget deficit and national debt and with lower approval ratings than Bill Clinton had a dozen years later, as David Frum, a former speechwriter for George W. Bush, remarks in his book Comeback (2007). He adds: “Running as a Reagan conservative, Bob Dole lost in 1996…. Had we nominated a Reagan-style conservative in 2000, we would certainly have lost again.”

Yet the spirit of insurgency has continued to animate the GOP, and whoever wins this year’s primary will have no choice except to embrace it, even as he realizes that his electability will hinge on the general perception that he doesn’t really believe the conservative ideology he espouses.

—February 9, 2012. This is the first of two articles on conservatism and current politics.

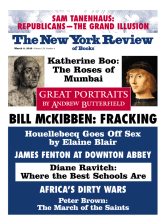

This Issue

March 8, 2012

Schools We Can Envy

Work, Not Sex, At Last

Why Not Frack?

-

1

Michael D. Shear, Jeff Zeleny, and Jim Rutenberg, “Romney Tax Returns Show 2-Year Income of $45 Million,” The New York Times, January 24, 2012. ↩

-

2

Bret Stephens, “The GOP Deserves to Lose,” The Wall Street Journal, January 24, 2012. ↩

-

3

Peter Hamby, “Gingrich Sharpens Attacks Against Romney’s Wealth,” CNN Politics, February 3, 2012. ↩

-

4

Nicholas Confessore, “Returns Suggest Gingrich Pays Higher Rate in Taxes,” The New York Times, January 19, 2012. ↩

-

5

Eric Lichtblau, “Gingrich’s Deep Ties to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac,” The New York Times, February 3, 2012. ↩

-

6

Shira Toeplitz, “Santorum and Gingrich Share Complicated Past,” Roll Call, January 26, 2012. ↩

-

7

“Welcome to the Machine,” Washington Monthly, July–August 2003. ↩

-

8

See Katrina Trinko, “Santorum and Earmarks,” National Review Online, January 6, 2012. ↩

-

9

James Kirchick, “Angry White Man: The Bigoted Past of Ron Paul,” The New Republic, January 8, 2008. ↩

-

10

Brian Stelter, “Republican Debates Are a Hot Ticket on TV,” The New York Times, October 16, 2011. ↩

-

11

Kate Zernike and Megan Thee-Brenan, “Poll Finds Tea Party Backers Wealthier and More Educated,” The New York Times, April 14, 2010. ↩

-

12

See, for example, Robert Schlesinger, “Poll: Most Americans Support Obama Deficit Plan to Tax Rich,” U.S. News & World Report, September 20, 2011. ↩

-

13

“Congressional Performance: 5% Say Congress Doing Good or Excellent Job,” Rasmussen Reports, January 31, 2012. ↩

-

14

Kate Zernike, “Support for Tea Party Falls in Strongholds, Polls Show,” The New York Times, November 29, 2011. ↩

-

15

Theda Skocpol, “Mitt Romney, the Stealth Tea Party Candidate,” The Washington Post, February 3, 2012. ↩

-

16

Quoted in Richard H. Rovere, The Goldwater Caper (Harcourt, Brace, 1965), p. 118. ↩

-

17

Michael D. Shear, “Romney Attacks Obama’s Address as Nothing More Than ‘Tall Tales,’” The New York Times, January 24, 2012. ↩

-

18

Alan Bjerga and Jennifer Oldham, “Gingrich Calling Obama ‘Food-Stamp President’ Draws Critics,” Bloomberg, January 20, 2012. ↩

-

19

Joe Klein, “Obama’s Fairness Doctrine,” Time, February 6, 2012. ↩

-

20

Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen, “Newt Gingrich: The Master of Disguise,” Politico, January 23, 2012. ↩

-

21

Hofstadter’s essay was first collected in The New American Right (1955; it was updated and expanded in the volume The Radical Right, in 1963; both edited by Daniel Bell), pp. 82, 76; other quotations from The Age of Reform (Vintage, 1955), pp. 4–5. ↩

-

22

Willmoore Kendall and George W. Carey, The Basic Symbols of the American Political Tradition (Catholic University of America Press, 1970; repr. 1995), p. ix. Kendall died in 1967. These lectures were assembled posthumously. ↩

-

23

For an early, Straussian discussion of Wilson as subverter of constitutional ideals, see Paul Eidelberg, A Discourse on Statesmanship (University of Illinois Press, 1974), pp. 279–362. For a more recent one, see Ronald J. Pestritto, Woodrow Wilson and the Roots of Modern Liberalism (Rowman, Littlefield, 2009). See also Jacob Heilbrunn, “The Claremont Institute, Ron Paul, and the State of Conservatism,” on The National Interest website, October 11, 2011. ↩

-

24

See Sean Wilentz, “Confounding Fathers,” The New Yorker, October 18, 2010. ↩

-

25

Alan Brinkley, The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century (Knopf, 2010), p. 256. ↩

-

26

Phyllis Schlafly, A Choice Not an Echo (self-published, 1964), p. 108. ↩

-

27

Draft of “selling memo,” spring- summer 1954 (Buckley Papers, Yale University). ↩

-

28

See my Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (Modern Library, 1998), p. 487. ↩