The work of Wilhelm Lehmbruck makes one realize how rare it is in the sculpture of any era to see, on the faces of figures, subtle and convincing states of feeling. The emotions expressed by the men and women done by this German artist, who died in 1919, at thirty-eight, are almost never extreme or showy, even though he is generally labeled, somewhat for convenience’s sake, an Expressionist. The mood conveyed by his female figures is, rather, serene and undemonstrably self-confident, while his far fewer male figures seem caught in moments that shift from brooding thought to stony anger. Looking at either—and the very faces of Lehmbruck’s people are beautiful and handsome in fresh and delicate ways—we feel invited to linger in what might be called a mental atmosphere, an attitude about life.

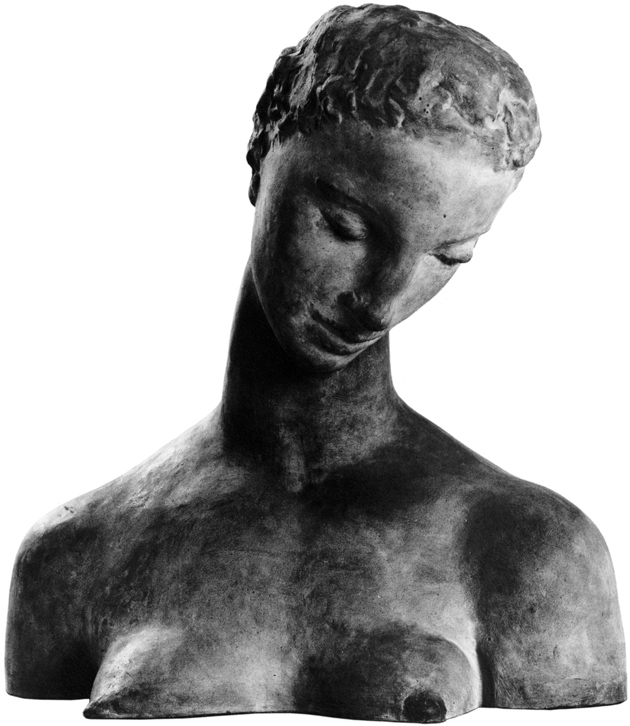

Lehmbruck is now the subject of his first New York show in almost twenty years. The last one was also held at the Michael Werner Gallery, and while the present exhibition is perhaps even better, it is more of a first-rate introduction to the artist than a distillation of his achievement. For viewers who have never heard of Lehmbruck, whose only American retrospective was held in 1972, at the National Gallery of Art, it has enough strong pieces to make one want to see more. In its dozen or so mostly bust-sized sculptures (and numerous etchings), it certainly conveys the elementally different way the artist thought about the sexes. The sculptures of women in terra-cotta, bronze, and cast stone (which is made from cement, stone dust, and pigment) often express a kind of gentle, and unsentimental, acceptance of existence. Most of these figures, with their high, small breasts, shyly tilt their heads away from us. Lehmbruck is such a virtuoso of shyness, however, and there is such a variety of textures and sand and salmon tones among these works that almost every woman appears caught up in a different thought.

Head of a Thinker (1918), on the other hand, the one sculpture of a male figure, is, in its dark gray cast stone, mysterious and ominous. It is a bust of a lean and physically powerful young man. His head is domed and he leans downward. His eyes, unnervingly, could be staring or could be mere slits, and his arms are cut off just below his shoulders—giving him altogether the appearance of some wounded and ashen bird of prey. Head of a Thinker is like the chopped-down remains of a monumental piece, and as such it hints at what the Werner Gallery, for lack of space, understandably cannot include: any of the sculptor’s large works. Without them the full scope of his art is missing.

Lehmbruck’s story is that of an artist who never lost his affinity for traditional modes, even as he kept transforming them from within. His insight was that he didn’t need to give up the tenor of classical, or academic, sculpture—the heroic, idealized, unclothed male or female figure; the seeming impersonality; and the base or pedestal, to emphasize the work’s immaculate distance from life—even as he innovated. Born in Duisburg, in Westphalia, the son of a miner and apparently from a background where being an artist was something of an anomaly, he drove himself forward on pure ironclad talent and ego. He was in art school in Düsseldorf at age fourteen, and by his middle twenties, already a star at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, he had got himself to Italy to study Michelangelo and had traveled to England, France, and elsewhere.

In 1910, now twenty-nine, Lehmbruck moved to Paris with his wife Anita and the first of their eventually three sons. There he became familiar with the work of Matisse, Brancusi, Archipenko, and Modigliani, among others, none of whom was making heroic or classical sculpture as he was and yet to whose more personal and unorthodox efforts he must on some level have paid serious heed. (How involved he was with new art, and dance, in the French capital is largely the subject of the profusely illustrated Kneeling Woman 100 Years: Wilhelm Lehmbruck in Paris 1911). Temperamentally more conservative than these artists, though, he had already set his sights on the two pillars of a more established approach.

The first was Rodin, who since the 1880s had been practically reinventing sculpture. At the very least he was transforming it into a painting-like medium that could show marble and bronze in more liquid, light-catching, and voluptuous ways. The second was the younger Aristide Maillol, whose firmly rounded and perfectly proportioned female figures represented a kind of chastening of, and a way to get beyond, Rodin. Maillol, to our eyes, like the later Henry Moore, is hard to dwell on for long; but in his day the unadorned, massively scaled, and smoothly and tautly curvilinear look of his women gave neoclassical sculpture an abstract air in keeping with the times. More than Rodin, Maillol seemed suited to the abundant and uniform light and the uncluttered, open spaces of modern buildings.

Advertisement

Lehmbruck essentially combined the best of the two Frenchmen, and in the process cut loose their limitations. Not that he went about it calculatedly, but one can see in his work that he was after the storytelling and operatic quality of Rodin. The very title Head of a Thinker refers to Rodin’s Thinker. Sheathing this quest, though, in Maillol’s less demonstrative—or less artfully busy—packaging, Lehmbruck gave Rodin’s drama a needed veil. He showed how sculpture could present an emotion, even a tragic one, but could do so unostentatiously, psychologically.

In the few years that, as it turned out, Lehmbruck had in Paris, he created at least two masterworks: Kneeling Woman (1911), which shows a slightly draped figure of great contemplative sweetness, and Standing Youth (1913), where the entirely nude figure, seen in a moment of Hamlet-like introspection, has one leg up on a little rise. Both of these larger than life-size and rather elongated cast stone works are in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, and they used to be regularly on view. Although clearly big enough to hold their own in outdoor public places, they were set in the galleries, probably because cast stone, like marble, can deteriorate outside. To be standing by these physically grand and emotionally tender works, which usually were placed among paintings by Beckmann and Kirchner and Kokoschka, was to feel that one had entered a grove of unguarded, private feelings.

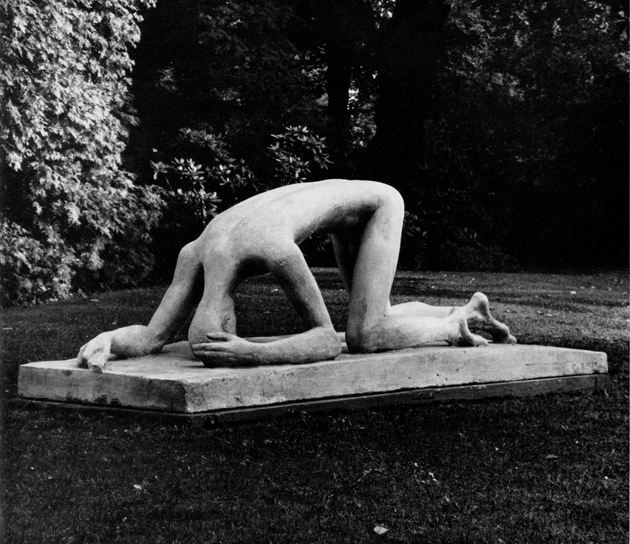

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Lehmbruck and his family went back to Germany, ultimately settling in Berlin. He was never mobilized, and he seems to have been free to exhibit and even travel. Yet he served for a time as a medic, and the deaths of people he knew on both sides of the conflict clearly affected him, as he made two of the most powerful responses to the war, The Fallen Man (1915–1916) and Seated Youth (1916–1917). I have not seen the actual sculptures, but a number of writers have called them the finest Lehmbruck made. The Fallen Man, in photographs, is an amazing conception. Almost eight feet long, it shows a large-boned and very lean nude man crawling on his knees and elbows. His bowed head comes down to the ground as well, giving him the appearance of some lumbering, inhuman thing—an observation that Lehmbruck might have welcomed, as his subject was war’s degradation as much as its piteousness.

The less colossally abject Seated Youth, where a nude figure slumps forward—and, again, we don’t see the man’s face—is marked by the same ruthless simplicity. It takes a while to realize that this lanky figure, who feels like our contemporary—he is like a basketball player whose long legs become ungainly when he sits—represents another of Lehmbruck’s rethinkings of classical statuary. By the time he started it, toward the end of 1916, the sculptor (and eventually his family) had moved to Zurich, possibly to avoid conscription. What his state of mind was in the latter years of the war is hard to determine. Like his own Seated Youth, Lehmbruck had for some time been profoundly depressed by the war’s butchery. In a state of “despair,” it is often said, he took his life in March 1919, after he had gone back to Berlin, in his studio.

It should be added, though, that right up to the end recognition and prestige continued to come his way. In Zurich he had portrait commissions and found knowing well-wishers for his work. There he fell deeply in love with the young Viennese actress Elisabeth Bergner, then at the beginning of a long career on stage and in film. She modeled for him and he drew her often. Their love was unconsummated, but it nearly broke his marriage. It has even been conjectured that he killed himself because he was rejected by Elisabeth. (It is also possible that he was thrown into a crisis because he felt guilty in relation to his wife Anita, and that this compounded the guilt he felt in being alive and successful when so many men his age had been slaughtered.)

What makes Lehmbruck a modern artist has much to do with his receptivity to new materials such as cast stone, and to his desire to redo forms with slight variations. This is evident in the Werner show. His stature in art history stems as well from his being an initiator of German Expressionism, and this can be sensed in the “Gothic” quality of his elongated figures and in his prints, where his figures can have edgy, unsettling demeanors. But what makes Lehmbruck wonderful has to do with the spirit of reflectiveness he created in his sculpture. It is a matter of the slightly burdened yet regal bearing of his men and women and, of course, their faces, which often seem to be looking more inward than out. (His two principal wartime works are in part about how to do figurative sculpture without showing the face.)

Advertisement

Master of quiet moments as he was, Lehmbruck’s effect, when one is close enough to his work, is visceral. It has probably best been expressed by the late Joseph Beuys. When, in 1986, the performance artist and sculptor won the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize, he said in his acceptance speech, with his usual flair, that Lehmbruck had been his “teacher,” even though they never met. Beuys told how one day he chanced on a book that reproduced a Lehmbruck sculpture, and while at the time he had no thought of being an artist, he “immediately” knew that sculpture of some kind was what he wanted to do. Beuys, whose own work was cast as a kind of fairy tale, could put a fable-like spin on anything. But in describing how his life was transformed by looking at a photograph of a Lehmbruck, he somehow wasn’t being all that far-fetched.