This essay is based on a talk given in the Reims Cathedral on its eight hundredth anniversary in 2011.

The France of the ancien régime had sites of sacred commemoration—above all in cathedrals and abbeys—where the monarchy and the church entered into a ritual alliance of immense symbolic significance. The monarchy received consecration from the church while the church secured protection from the monarchy. No other country in medieval Europe enjoyed a comparable symbiosis of crown and altar. By contrast, in the Holy Roman Empire, the Investiture Controversy set the power of the emperor to appoint bishops against the principle that the church should not be subject to secular interference. In England, Thomas à Becket was martyred in 1170 in the struggle between king and church. It was only in the France of the Capetian kings starting in the late tenth century that peace reigned between the monarchy and the church hierarchy, and it was largely this peace that allowed the beauty and magnificence of the cathedrals in the French crown lands to flourish.

The first site of sacred commemoration was the royal abbey of Saint-Denis. It stood outside the gates of Paris, the town that in the twelfth century was becoming established as the capital. The abbey church had served the kings of France as a burial place since the days of the Merovingian Dagobert I (circa 603–639). Here, the rulers slept at the feet of Saint Denis, the first bishop of Paris, whom the Middle Ages regarded as a disciple of the Apostle Paul. In the thirteenth century, in the days of Saint Louis (1226–1270), a lacy Gothic basilica was erected over their graves, arranged by dynasty. One of the great achievements of medieval French architecture in both its churches and its castles was the representation of sovereign state power as ceremony. Enshrined at Saint-Denis was the Oriflamme, the battle standard of the French kings, and the royal insignia were kept in its treasury.

The French crown’s second site of sacred commemoration was the Cathedral of Reims. There, on Christmas Day in 498 AD, Clovis, king of the Franks, was baptized by Rémi, the archbishop of Reims, who according to a later legend anointed him with oil brought by a dove from heaven. It was the miraculous birth of the Christian kingdom of France. Almost all the kings of France up to the Revolution would be crowned in the Cathedral of Reims and anointed with heavenly oil from the inexhaustible sacred phial.

That oil was kept at the grave of Rémi in the Abbey of Saint-Rémi outside the city gates, and on coronation day, the abbot would hand it over to the archbishop at the threshold of the cathedral. Because of this unique privilege, Reims Cathedral, whose eight hundredth anniversary was celebrated this past year, became the queen of French cathedrals. The splendor of its majestic architecture and its sensual wealth of sculptural decoration are not just a fact of art history but a brilliant mirror of the unique importance of this church for the kingdom of France.

When Archbishop Alberic de Humbert laid the cornerstone for the new cathedral in 1211, he and the cathedral chapter were faced with a daunting task. The archbishop of Reims was the metropolitan of an extensive ecclesiastical province whose twelve suffragan bishoprics encompassed the better part of what had been the Roman province called Belgica Secunda. To the east, the province of Reims bordered on the imperial archbishoprics of Trier and Cologne. There had been active church construction in northern France since the middle of the twelfth century. Some of Reims’s suffragan bishoprics—the powerful and ambitious diocese of Laon, for instance—had already put up impressive new cathedrals. Those other new structures could not be allowed to eclipse the metropolitan cathedral. It had to outdo and outshine them. It was a demanding requirement.

Thirty-two years earlier, Philip II had been crowned in Reims and since then he had powerfully advanced the prestige of the monarchy. By 1211, he had already driven the Plantagenets from Normandy and Anjou, and three years after the cornerstone was laid, he would go on to win a decisive victory over the emperor and the English king at the Battle of Bouvines. That made him the most powerful ruler in Europe. Even if we cannot assume a direct connection between the beginning of construction of the cathedral and the king’s victory, the new coronation cathedral was nevertheless expected to reflect the increased prestige of the Capetian monarch.

Reims Cathedral has been the subject of numerous architectural and art-historical studies, but I would speak instead about the cathedral’s spiritual message and symbolic form and recall the extinguished ritual tradition that once filled its interior with life. The truth of the matter is that the positivistic discussions of forms, stylistic changes, and dates, as fundamental and useful as they may be, always bring to mind Proust’s unforgettable essay “The Death of the Cathedrals” and its sense of a post-religious society.1 And so I am going to be more poetic and evocative than scholarly. I think the cathedral deserves no less on this festive occasion.

Advertisement

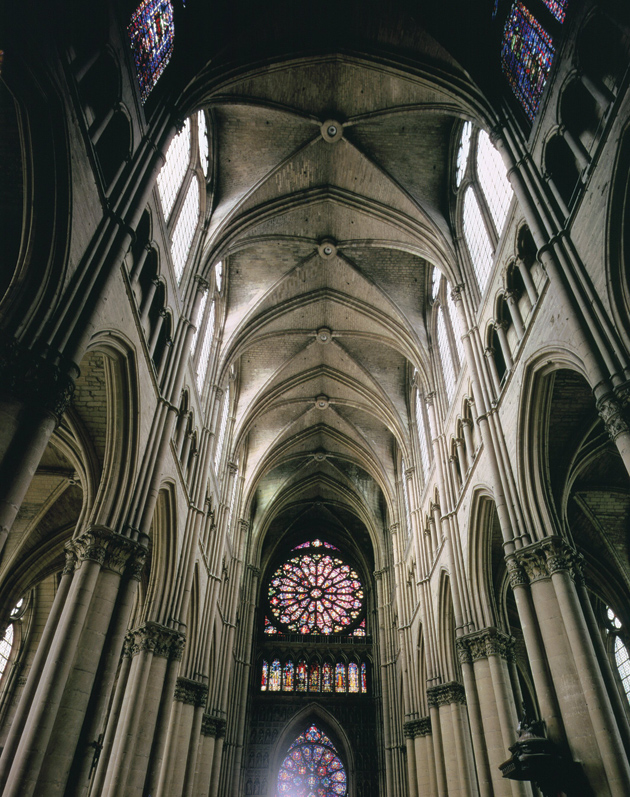

First we should consider Reims Cathedral as an architectural reflection of the Heavenly Jerusalem of the Apocalypse. Of course, cathedrals rose above many medieval towns in the French crown lands—gigantic, inspired, sacred structures. In Reims, however, this transcendent effect is raised to imaginative heights by a unique interplay between the cathedral’s architectural frame and the eloquent detail of its sculpture. Like a heavenly city, the entire building is surrounded by angels. They are larger-than-life figures with their wings outspread, as if they had just descended from on high, at once ethereal and vividly corporeal. They are the guardians of the royal temple of Our Lady of Reims.

It is the choir that displays the radiance of this angelic—one is tempted to call it Dantesque—architecture at its most magnificent. A ring of five chapels surrounds the apse. Above them rise the piers of the flying buttresses, from which arches branch to connect them to the choir. We know that Gothic buildings had a subtle play of balance: force and counterforce. During the nineteenth century, the epoch of iron construction, architects and artists justly admired them as masterpieces of medieval engineering genius.

But such commonsense praise only touches the technical aspects of an architectural miracle like Reims Cathedral. The buttresses, after all, are only a structural element, born of necessity but iconographically mute. In Reims, this was the point at which the imagination of the theologians went into action. For centuries they had lent allegorical significance to the forms of ecclesiastical architecture—its pillars and columns, porches and windows. In Reims, they seized upon the new forms of the flying buttresses and crowned the tops of the piers with open tabernacles and pyramids. Inside them they placed the angels I have already mentioned, whose smiles seem so radiant that it is hardly an exaggeration to celebrate them as the most charming heavenly envoys the art of the Middle Ages had produced up to that time. These guardian angels transform the tops of the buttresses into the gates of the Heavenly City. Ecclesiastical architecture becomes pure image. No other cathedral deploys such intensely symbolic poetry, a poetry that makes Notre-Dame de Reims the most beautiful of the French episcopal churches.

Secondly we should consider the cathedral in its role as the house of the saints and protector of their relics. The year 1793 brought a secularizing attack that brutally amputated the ritual life from the cathedrals: the confiscation and melting down of their sacred reliquaries. Until that year, the structures for the display of reliquaries stood in the cathedral choirs. They were not just gilded, but more importantly were decorated with images. The presence of the saints through their relics made the cathedrals into sites of ritual remembrance. Their disappearance left behind mute, emptied spaces in which post-religious observers experience a shiver of the sublime—“space as a symbol of spacelessness.” Thus closes one of the best-known essays on the subject.2 The eight hundredth anniversary provides an opportunity to pause and recall the long life of ritual observance that once filled the cathedral.

The revolutionary commissars of 1793 catalogued at least six reliquary shrines in the treasury of Reims Cathedral. No trace of them is left. Old views of the high altar show two of them next to the famous large cross. We don’t know whose they were. The most precious sacred relic was the body of the martyred Pope Callixtus I, who died circa 222 AD. It was contained in a shrine with no less than fourteen figures and was venerated in one of the chapels along the choir ambulatory. A statue of Callixtus stands at the threshold of the cathedral in the porch of the northern transept once used by the canons: a solemn figure clothed in splendid pontifical robes as if veiled in incense. The statues of the saints at the cathedral porches were signposts to the bodies of the saints within.

The Gothic interior was above all full of reminders of the two early Christian saints who were also bishops of Reims: Nicasius (died 407 AD) and Rémi (circa 437–533 AD). The martyr Nicasius had been beheaded by Vandals on the doorstep of the church. In front of the rood screen of the cathedral, worshipers could venerate a stone stained with his blood. On the inner side of the main portal stood Nicasius’s statue, holding in its hands his severed head, which he himself carried to the high altar. The cathedral possessed a reliquary bust that presumably preserved it.

Advertisement

On the same northern portal there is another statue of him with an intensely expressive severed head. Again, we experience the symbiotic relationship between the sculptural signpost and the body of the saint. No, the cathedral was anything but empty space. It was filled with the memory of saints, legends, and miracles.

With the other Reims saint, Bishop Rémi, we come to the third subject of my talk: the cathedral and the consecration of the monarchy. The cathedral treasury contained Rémi’s golden chalice and reliquary bust. At its entrance, his statue and the baptism of Clovis were to be seen. There is not enough time to pursue the many images depicting the ceremonial consecration of the king. The interesting question for us is how the ritual and topography of the ceremony helped shape the visual symbolism of the cathedral. The “Great Altar” at which a new monarch was anointed and crowned was erected in front of the choir, in the center of the transept. On the exterior of the building, at the four corners of the transept, rose massive towers. On them the series of tabernacles crowning the flying buttresses is continued, but here they have become taller and wider and in their interiors it is not angels standing guard, but fourteen colossal statues of kings, proclaiming that the transept with its high altar and towers was France’s coronation church.

From the outset, the renewal of ecclesiastical architecture in the French crown lands was linked to images of the monarchy and its commemoration. In the ancient abbeys, the graves of the Merovingian and Carolingian kings were renovated. Statues of kings were installed at the church porches. These monumental royal memorials reached their high point under Philip II (1165–1223) when a gallery of twenty-eight kings was installed across the façade of the Cathedral of Paris.

The same idea was taken up by the builders of the Cathedral of Reims. Here, the monarchs are not arrayed side by side; instead they appear as imposing individual statues of varying format and physiognomy. They are moving witnesses to the consecration of the French king. There is no consensus about whether they represent biblical kings or the monarchs of France, but in a deeper sense, it doesn’t matter. Each one is a king, anointed by a priest, be it David by Samuel or Clovis by Rémi.

And again, the image of the royal consecration appears on the exterior of the cathedral as well, on its façade, where the structure appears even more magnificent. Down below, at the main entrance, Mary is being crowned as the patron of the cathedral and the statues invite the faithful to the great Marian holidays, from the Feast of the Annunciation to Candlemas. But up above, the façade is crowned by a gallery of kings. In the middle is the baptism of Clovis, the ultimate image of the symbiosis of church and crown represented by the Queen of Cathedrals.

I should say, finally, how moved I am as a German to be permitted to speak in this place on the occasion of its eight hundredth anniversary. Not quite a hundred years ago, it was German shells fired by our fathers and grandfathers that set fire to and devastated Notre-Dame de Reims. In September 1914, a blow was struck at the heart of France. Among the smashed sculptures found lying before its portals was the grievously damaged face of the famous smiling angel. In the midst of the mourning, the phrase “the smile of Reims” was born and the image of the wounded smiling angel unleashed a cry of outrage around the world.

But looking at the image now, almost a hundred years later, with the cathedral’s wounds healed, this head seems more a promise of happiness, just as it once stood at the porch and promised the martyr Nicasius the bliss of Paradise. This promise of happiness has outlived the destruction and pain, triumphed over outrage and hatred, so that today a German can be a “Friend of the Cathedral of Reims” and celebrate its beauty. For that I am humbly grateful, still a bit awed, but above all happy from the bottom of my heart.