Two years ago The Wall Street Journal calculated that in a typical National Football League game, the ball is live for only eleven minutes. The game clock runs for an hour, but most of that time is spent between plays; and the television broadcast of a game, which includes advertising and a halftime show, runs for a good three hours or more. If you think Americans might be impatient with being asked to commit that much of their time for eleven minutes of action, think again. Professional football is the most reliably popular form of television entertainment. During the season, half of a week’s ten top-rated shows are often either professional football games or football-related spinoff programming, like pregame shows and omnibus reviews of a week’s games.

You might think that sports journalism ought to be for fans who didn’t attend a game and want to know what happened. Broadcast sports journalism originated on the radio, and was meant to confer a feeling of being there to people who weren’t. But it has been clear for a long time that an additional function of sports journalism—today, the prime function—is to create a setting, not to report on results. American social masculinity now makes its primary home in the conversational bonhomie that surrounds sports. This kind of talk originates in sports journalism and then spreads to bars, parties, airport lounges, and dinner tables. Newspapers have had sports columnists, whose primary job isn’t to give results and who typically are their employers’ most popular and valuable staff members, for eons. Radio sports announcers more directly “call” games in progress, but the best ones learn how to develop an intense bond with the public; remember that Ronald Reagan’s early professional training came from announcing baseball games on the radio in Iowa.

On television, sports fans can see the game, but announcers are an essential part of the experience. Somebody has to fill all that time between plays, explain what’s going on (it goes by awfully quickly), give background information about the players, coaches, and competitors’ games, and, most important, offer up emotional guidance and surrogacy. By long-established genre convention, announcers of televised sports usually come in pairs—one member more phlegmatic, to do the play-by-play, and one more florid, to provide the color commentary. The play-by-play man tells you what just happened, and the color man offers up feelings; your own reaction and that of your friends, gathered in front of the screen, are cued and shaped by the intricate interplay of their reactions.

Important as they are in mediating and intensifying the relationship with the audience, sports announcers are in an odd position. The top announcers are hugely, and durably, popular, but only as connecting figures between the players and the fans. With a few very rare exceptions like Reagan—or more recently Keith Olbermann, who made a successful transition from sports to political commentary—they cannot survive outside of their symbiotic relationship with the athletes they are covering. Successful announcers are actually in a superior position to almost all athletes, who have very brief and brutal careers, but it’s part of their job to make themselves appear secondary.

Howard Cosell, of ABC, who died in 1995, was the most famous television sports announcer ever. He was a star for three decades, and during his early-1970s heyday, which coincided with the maximum reach of network television, he was a ubiquitous figure in American culture. He performed cameos as himself in two Woody Allen movies and in two episodes of the sitcom version of The Odd Couple. He couldn’t walk down the street anywhere in the country without drawing a crowd. No self-respecting comedian could fail to have a Cosell impression in his repertory. He frequently testified before congressional committees, and mused for years about running for the United States Senate from New York. He published several volumes of memoirs. There was a small secondary industry in other sports announcers and columnists’ never-ending debates about Cosell, and the debates went beyond the confines of the sports world. Michael J. Arlen, in The New Yorker, and Benjamin DeMott, in The Atlantic Monthly, wrote essays about Cosell’s cultural meaning.

In case you missed all this, the first thing you need to know about Cosell is that he was not the sports announcer type. Cosell mainly worked as a color man, and most of them are former athletes, bluffly amiable. Cosell was an ex-lawyer, tall, not handsome, who delivered generous helpings of verbose, stagy erudition in the accents of his Brooklyn Jewish youth and the mannered, uncool cadences of a 1930s radio announcer. Cosell’s boss, Roone Arledge, caught his peculiar mode of speaking pretty well in this quote, which comes from Arledge’s memoirs: “From the desperation of your tone, the bon vivant who is Roone Pinckney Arledge is beseeching me to rescue the trifle he’s devised for Monday evenings. Am I not correct?” Another part of Cosell’s persona was that he could be tough and confrontational. On a medium built for comfort, Cosell played the part of an ostentatiously candid, crusading liberal truth-teller.

Advertisement

Cosell’s fame was of an especially fleeting kind. He is much less remembered today than are the best of the athletes he covered, though their careers were far shorter than his. (Most of his work is gone forever, because ABC destroyed its videotape library in the late 1970s.) That’s fair—life inside the broadcast booth is inherently less interesting than life on the playing field—but it makes being his biographer difficult. Mark Ribowsky, a veteran sports and entertainment journalist, has to work very hard to persuade us that Cosell deserves to be the subject of a long biography. In the introduction alone, he calls Cosell a “transformational figure,” an “outlaw,” and an artist, and refers to his heyday as “the Age of Cosell.” Because he can only attack after having previously built up (otherwise why bother?), his book seesaws between exaggerated praise for Cosell and exaggerated disillusionment over Cosell’s failing to be the great man Ribowsky has previously tried to persuade us he was. Sentence by sentence, Ribowsky’s unrelenting, hard-sell approach regularly produces clunkers like this:

But if Ali won few points for originality as a phoenix rising, he clearly had more than a few miles left on him—several of which were logged a bare three weeks later on December 7 when he took on another beautiful bum, Argentinian Oscar Bonavena, in the prime-time venue of Madison Square Garden, New York being still the only state to officially reinstate his license (the Quarry bout having been a one-off deal).

Or this:

Because [Frank] Gifford was joined at the hip with [Don] Meredith, and laid down a soothing, low-key groove in general—and treated Cosell with a compliant respect that sometimes parted for a verbal pinprick that was not appreciated—his arrival made for a nuanced shift texturally and, significantly only to Cosell, a shift in the axis of power in the booth from two career announcers to two ex-jocks.

But Ribowsky isn’t wrong in thinking that somewhere in the interplay among Cosell’s life story, the stories he covered, and the institutional rise of televised sports lies significant material about American culture. Born in 1918 to children of immigrants from Russia who had made their way to the middle class, raised on Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, Cosell seems to have been fascinated with sports announcing from early childhood. He was an excellent student who followed the approved upward and assimilationist trajectory for men of his generation and subculture: law school, military service, marriage, family, a move to the suburbs. But he couldn’t rid himself of the sports bug. His legal practice, at a small firm, included athletes and other clients connected with sports; one of these was the Little League in Brooklyn, and that association led to his first announcing assignment, on ABC radio in the summer of 1953, of a program about Little League baseball.

Cosell was unremittingly energetic and persistent, and he managed to parlay this small-time entrée into other, more significant jobs. Within a few years he had left his law practice and was working full-time for ABC Sports. Cosell, the unlikely announcer, and ABC, the underdog television network (it was created in the 1940s by the Federal Communications Commission’s pressure on NBC to divest itself of one of its two radio networks), rose in tandem.

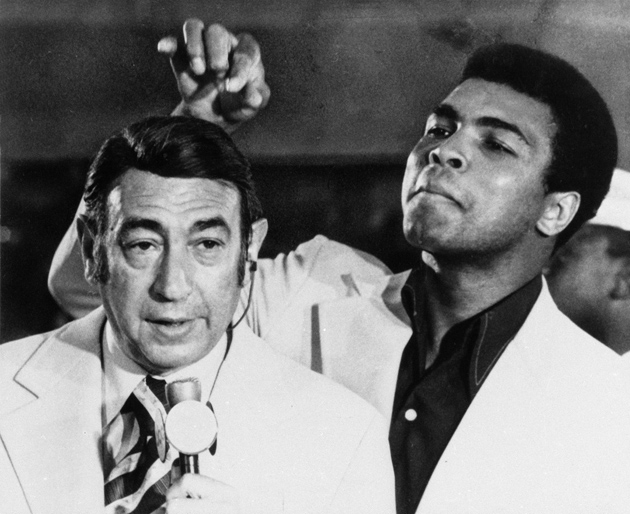

Cosell became a star by covering a bigger star, Muhammad Ali, the great heavyweight boxer. Even before he encountered Ali, Cosell had established himself as a boxing announcer—in particular, as a champion of black boxers. Ali was unusual not just as an athlete but also as an unforgettable and irresistible public figure. His heyday coincided with the apotheosis first of the civil rights movement and then of the Black Power movement. Ali was not an exemplary, dignified black pioneer like Rosa Parks or Jackie Robinson. He was brilliant, gorgeous, showy, and political. When he joined Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam in 1964, then changed his name from Cassius Clay, and then refused an induction notice from the United States Army on religious grounds, the sportswriting establishment, led by Cosell’s arch-enemy, Dick Young of the New York Daily News, was horrified—but Cosell was supportive. He was one of the first sports journalists to call Ali by his new name, and, more important, during Ali’s three-and-a-half-year exile from boxing because of his draft resistance, Cosell was one of the only sports journalists to remain loyal, sympathetic, and attentive.

Advertisement

His reward was to have most-favored-nation status among journalists when Ali made a sensational comeback in the early 1970s, with exclusive interviews at every key juncture. Also, Ali and Cosell made for a great pair on television. Whether or not they were friends in the conventional sense is probably impossible to determine—though Ribowsky tries—but they had chemistry. Opposites in all the obvious ways, they were both braggarts, both kidders, both self-dramatizers; they keyed off of each other like the expert performers they both were.

Ribowsky has unearthed a Rosebud-style moment in one of Cosell’s memoirs that he offers as explanation for the later success of his pairing with Ali. Just after World War II, Cosell, then in law school, encountered Stanley Kramer, the film director, who was trying to decide between two projects that were both angry fictional exposés of anti-Semitism, Arthur Laurents’s play Home of the Brave and Arthur Miller’s novel Focus. Cosell voted for Focus, but Kramer said that he thought it was too similar to Gentleman’s Agreement. Instead, Cosell remembered Kramer’s telling him, he’d make Home of the Brave, except that “I’ll make the Jewish boy black and I’m gonna deal with the great problem of America to come. The black problem.”

Cosell himself was the sort of Jew who would seem echt-Jewish to the outside world and assimilationist to other Jews. He was raised Howard Cohen, though his family’s name change was arguably in the direction of closer conformation to its original, old-country version, Kozel. He had no religious education, he married a Protestant, and he and his wife raised their two daughters without any religious practice or identity. His wedding and his funeral both took place in churches, one Presbyterian and one Methodist. But as it was for many people of his generation and experience, Cosell’s Jewishness was ineradicable. He was instinctively Zionist, and he was always quick to attribute career setbacks to anti-Semitism.

Whether or not it represented a conscious choice, the character Cosell played on television combined every possible goyische stereotype of Jews: hook-nosed, brainy, pushy, left-wing. His popularity may have represented a personal triumph over the American viewing public’s anti-Semitism, and it also may have represented the deep fetishistic appeal of the Other when presented in just the right way; white America loved minstrel shows, Amos and Andy, and Birth of a Nation, too. In any case, Cosell was able to empathize with black athletes in a way that was impossible for the silent-majority types who dominated sports journalism at the time, and he felt more comfortable crusading for ethnic advance by proxy, on behalf of Ali and others, than directly. Perhaps the long-running project of getting the American public accustomed to a multiracial cohort of sports heroes required a white announcer who could be read as “different,” but not quite so much so as the athletes themselves, to serve as guide.

In 1969 Roone Arledge, then the president of ABC Sports, assented to the odd idea of broadcasting one professional football game a week on Monday night, rather than Sunday afternoon. He knew that he had to dial up the entertainment quotient of the production in order to compete with prime-time comedies and dramas. To accomplish this he wound up creating a team of three in the broadcast booth: Frank Gifford, the former New York Giants halfback, Don Meredith, the former Dallas Cowboys quarterback, and Cosell. Monday Night Football was an enormous and surprising ratings success that, among other things, helped signal just how all-powerful a force in American culture professional football was becoming. (One Monday night in 1974, both Ronald Reagan and John Lennon made guest appearances in the broadcast booth.)

Like the CBS newsmagazine show Sixty Minutes, which started at around the same time, Monday Night Football is still on the air, forty years later, though now on ESPN. Cosell’s relationship with Don Meredith was his second most successful onscreen partnership, after the one with Ali, and it, too, had a generous element of vaudeville-era ethnic comedy, with Meredith playing the lovable, roguish country boy from small-town Texas and Cosell playing Cosell.

Cosell liked to present himself as a real journalist who offered the public hard-nosed, candid reporting, in contrast to the members of the “jockocracy” who mainly populated the stadium broadcast booths. And his critics often treated him as having betrayed the sacred precepts of journalism. David Halberstam, who disapproved of Cosell, once dismissively wrote, “instead of the probing journalist, he became the classic modern telecelebrity.” But such a simple opposition doesn’t scan in Cosell’s case. He was a member of the Friars Club, the gathering place for corny Catskills comedians d’un certain age, and the host of Battle of the Network Stars. In the mid-1970s, imagining himself to be the perfect person to pick up the mantle of Ed Sullivan, he launched a variety show on ABC called Saturday Night Live, which was quickly crushed in the ratings by the much hipper NBC show of the same name. And yet, Cosell was a good, aggressive reporter who regularly unearthed information ahead of his competitors. Long past his peak, he hosted a semi-investigative program called SportsBeat, and wrote a book called What’s Wrong with Sports.

It isn’t just that he was sui generis that makes Cosell hard to categorize; it’s that his role in American society was a complicated one. He was called upon to be part entertainer, part reporter, and part chaplain. One of the high points of his career was his taking a few moments of air time on Monday Night Football to announce that John Lennon had been murdered, and then quoting from memory a line from “Ode to a Nightingale.” Which is that, news or entertainment? Ribowsky, in one of the moments when he’s building Cosell up, offers this fight call as evidence of his greatness: “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!… It is over! It is over! It is over in the second round. George Foreman is the heavyweight champion of the world!” The audience could see for itself that Joe Frazier was down; Cosell’s function was to find words that would give the scene the emotional impact that it deserved and that the audience craved, and he did that well. Is that journalism? Does it matter?

At the height of his career, Cosell lived the peculiarly isolated life of a very famous person. Every Sunday, accompanied by his wife, Emmy, he would fly to whatever city was playing host to Monday Night Football. Every Tuesday morning he would return to New York and, according to Ribowsky, hang around the ABC headquarters building, hoping to get approval of his performance the night before. He moved to a penthouse apartment in a building on the East Side of Manhattan called the Imperial House. He drank a lot. Ribowsky disapproves of this kind of behavior, but a quote he’s gotten from Don Ohlmeyer, one of Cosell’s producers, puts a more sympathetic gloss on the excesses of Cosell in his baroque period:

Look, most people in entertainment are that way—they all act like children. Nobody I’ve known in the business—including myself—had an emotional age above fifteen. We are not normal people. Success can be here one day and gone the next, and it’s a hell of a long way down. Howard, as big as he became, never felt he was safe, and that feeling was infectious to those around him. And the kind of life Howard and I lived then was so unnatural, you couldn’t be a normal person. I used to travel two hundred thousand miles a year. But at least when I got into a town, I wasn’t constantly mobbed, harassed, and put under a microscope like Howard was.

Most of Cosell’s career was devoted to his announcing games and fights that his employer, ABC, had paid handsomely for the exclusive right to broadcast. The athletes and Cosell were talent employed by companies that were in a mutually beneficial business partnership, hired in the hope that their public presence would enhance the value of the partnership. Ribowsky tells us that Roone Arledge pre-cleared his selection of Cosell for Monday Night Football with Pete Rozelle, the commissioner of the National Football League, and that Rozelle would occasionally drop by Cosell’s apartment for a friendly cocktail. Cosell wouldn’t have succeeded if he hadn’t been persuasive as a tough-minded correspondent covering a story, but he was there to help the league and the network make money together, and he did.

Big-time sports is deeply woven into the texture of American society. They evolve in tandem. Can anybody name the heavyweight boxing champion of the world? Boxing still exists, but it has begun to feel like a cultural artifact from the vanished heyday of the American working class. Football is much more distinctively American than boxing—attempts to export it have mainly failed—and its triumph in popularity and commerce over all other sports is a little mysterious. The heavily armored players are hard to see, it’s violent, the action is highly sporadic, and the teams play fewer games than in any other major professional sport. Whatever the reason for its success, to maintain its position football has to absorb all the main currents of the culture as they present themselves.

David Halberstam was killed in an auto accident while on his way to interview Charlie Conerly, the New York Giants quarterback in the 1958 National Football League championship game against the Baltimore Colts, a muddy cliffhanger known as “The Greatest Game Ever Played.” Halberstam’s book on the game, had he lived to write it, would surely have noted that the great majority of the players were white, grimly determined, and not very well paid (their number included Howard Cosell’s future broadcasting partner Frank Gifford).

Today fewer than a third of NFL players are white, though whites still dominate some positions, like quarterback and kicker. Star quarterbacks can make more than $10 million a year. Linemen are enormous three-hundred-pounders, receivers have sculpted, tattooed bodies and do flashy little dances in the end zone when they score touchdowns, and stadiums are filled with luxurious touches like indoor box seats for high rollers. The exciting pass, not the dutiful run, dominates the game. Coaches use the latest information and communications devices to decide which plays to run and to get them to the players on the field. Everything that happens in American popular culture, marketing, ethnicity, and technology seems to manifest itself on the field.

Ribowsky is so closely attentive to the details of Cosell’s life that he doesn’t deliver explicitly on the promise of his book’s subtitle: that in addition to telling his main character’s story, he will explain “the transformation of American sports.” It’s possible to infer the kind of argument he’d make. Sports, and sports journalism, had a season, coinciding with Cosell’s heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, in which they opened up to an unusual degree of candor and inclusiveness about race and other large social issues. Then the moment ended and sports, along with sports journalism, became corporate, bland, and all about money and entertainment.

If this is Ribowsky’s big idea, it is far too simple. Professional sports by definition exist for commercial purposes, and always have; it’s just that long-ago forms of commerce seem authentic and endearing (think of the Depression-era agricultural advertising played for nostalgia on A Prairie Home Companion). When a commercial sport is successful, that is substantially because it has managed to be about what was going on in the larger society—the emergence of radio in the 1920s and 1930s, World War II in the 1940s, the emergence of television in the 1950s, and then civil rights and multiculturalism. Since the election of Reagan in 1980, the United States has become a far more market-dominated society than it had been before. Big-time sports have moved in the same direction as the country as a whole.

As in the country, among professional athletes economic inequality has increased dramatically; the highest-paid member of an NFL team can make fifteen or twenty times what the lower-paid members make. Everything that can be monetized, is. There are wildly popular NFL-licensed lines of clothing, souvenirs, and other products for all age groups. The Super Bowl has become a Las Vegas–like commercial extravaganza so lavish as to be beyond parody; its halftime shows, which used to present college marching bands, are now a venue for pop megastars safely far past their youthful prime, like the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, and Madonna. It isn’t very useful to try to understand all this as a fall from innocence and grace exemplified by Howard Cosell’s having let his schlocky side take precedence over his serious side. Instead, the changes over the years in professional sports show that they are very good at doing whatever it takes to maintain their uncanny hold on our attention.