The Book of Revelation, which closes the New Testament, describes a nightmare of apocalyptic visions. These famously include beasts, serpents, a bottomless pit, warfare in heaven, wild horsemen, and other horrors that are only partially relieved by the ultimate arrival of the New Jerusalem. (“And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.”) The very word “apocalyptic,” which occurs in most modern languages to designate such wild imaginings, derives from the Greek name for the Book of Revelation, Apokalypsis, which literally means unveiling, as does the Latin word from which “revelation” is borrowed.

But what goes on in the New Testament text is far more than unveiling. It is a blend of phantasmagoria and ecstatic prophecy that has defied rational explanation for nearly two thousand years. It was the last book to be accepted into the canonical New Testament, and for Christians in the eastern Mediterranean it did not finally find its place there until the fourth century. Yet it was hardly unique in the first Christian centuries. Historians of the early Church have come to recognize a whole genre of apocalyptic literature in Coptic and Syriac.

With the discovery of a hitherto unknown Coptic library of such writings at Nag Hammadi in Egypt in December 1945, the extent and popularity of noncanonical revelations suddenly became more apparent than ever before. The books in the Nag Hammadi library were admirably edited and translated by a team of scholars under the direction of James M. Robinson, who published them all together in 1977. Only two years after that Elaine Pagels, who had participated in Robinson’s project, introduced the new treatises to a large and receptive public in a book of her own, The Gnostic Gospels.

She invoked a variety of Christian heresies that tended to be lumped together in the general category of Gnosticism. This term referred to a mystical and privileged knowledge (gnosis) about the divine realm and the creatures that populate it. Pagels’s name for the new treatises has stuck, even though, as was recognized at the time, many of them are no more gospels than the Book of Revelation itself. But the celestial dramas that unfolded in the overheated fantasy of their authors undoubtedly put the Book of Revelation into much sharper perspective. Now, after so many years, Pagels has returned to this subject in her new study of Revelation. But she had not strayed far from it in her intervening works on Satan, Judas, and the secret gospel of Thomas. The apocalyptic universe is where she is most at home.

Modern interest in the visions of the Book of Revelation is perhaps nowhere more obvious than in the television series Apocalypse, shown on the European Arte channel in 2008 in twelve hour-long episodes, featuring discussions with forty-four supposed experts (myself among them). What emerged from this intellectual marathon was a breathtaking diversity of opinion on the nature and origin of the Book of Revelation, not to mention early Christianity itself and its unmistakably Jewish beginnings. Apocalyptic writings, such as Revelation, are frightening and difficult not only because the horrors they evoke are hard to imagine but also because they are equally hard to understand. Presumably their authors meant to communicate something to their readers and not simply to dazzle them with meaningless prophecies or visions. Prophets, from Elijah and Cassandra onward, would not have existed without an audience to respond to their outcries. The author of the Book of Revelation clearly wanted to be noticed. He left tantalizing hints about himself and the age in which he was writing.

His name was John, and he was writing on the island of Patmos, one of the northernmost of the islands known as the Dodecanese in the Aegean Sea. He found the time in which he was living deeply troubled. Pagels insists that Revelation must be considered wartime literature, although readers will look in vain for an explicit allusion to war on earth, even if there is no lack of war in heaven. But the allegorical beasts leave no doubt that the author saw himself confronted by a succession of enemies in the world in which he was writing.

His identity is as obscure as his revelation. He is most unlikely to have been the apostle John, brother of James and son of Zebedee, if he was writing, as seems probable, forty years or more after the crucifixion. He is equally unlikely to have been the same as the author of the Gospel of John, which displays a very different kind of Greek from the much less sophisticated Greek of Revelation. His invocations of Jesus Christ show him clearly to have been a Christian, but this does not mean that he might not have been a Jew. A searching analysis of his book by John Marshall has made a strong case for Revelation as a Jewish document, which raises the deeply complex issue of the Jewishness of the first Christians.1

Advertisement

Pagels wades into all this controversial territory with a confidence born of many decades of pondering this particular apocalypse along with many others. Any interpretation of John’s book must begin with the world in which he wrote. Marshall could legitimately claim that Revelation was wartime literature because he believed that it was actually written about 69 AD, during the Roman war against the Jews. But for Pagels the book was written later, in 90 under the emperor Domitian. She believes that the author had visited Pergamum, Ephesus, and Aphrodisias in Asia Minor in this period and imagines him pacing along the beach at Patmos. If his work is wartime literature, as she claims, we have to remember that there was no war in the region in 90. The war she has in mind was the one that led to Titus’ destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem twenty years before. But Revelation contains no allusion to that war or any other, either before or during the time of writing.

The patristic writer Irenaeus in the late second century was the first, so far as we know, to place the work at the end of the reign of Domitian, who died in 96. Pagels never explains why she opts for 90. Although Domitian’s reign may have seen some persecution of Christians, this was not part of any warfare. Later Christian tradition declared, without any textual support, that John had been forcibly exiled to Patmos, and Pagels seems to find this credible. Certain islands in the ancient world were well known as secure places for banishment, but Patmos was not among them. Why any Christian, let alone one so thoroughly imbued with Jewish learning and language as John, should have been put on Patmos defies explanation.

If, as Pagels suggests, he had been wandering about in Asia Minor, perhaps on a tour of the seven churches addressed in Revelation, he could just as well have been relegated to any number of islands off the coast. In fact, the only clear indication that John had any specific information about mainland Anatolia is his reference to a “throne of Satan” in Pergamum (near present-day Bergama, north of Izmir). Pagels identifies this with a temple of Zeus in the city, but unfortunately there was no cult of Zeus there before the next century. The throne of Satan was undoubtedly the great altar built in the second century BC that is now installed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Anyone who has seen it will know that it bears an uncanny resemblance to a gigantic throne.

As for John at Ephesus on the Anatolian coast or at Aphrodisias in the interior at the eastern end of the Maeander Valley (in present-day Turkey), there is no reason to think that he was in either place. Pagels’s suggestion that he would have seen stoneworkers at Ephesus constructing colossal statues of Vespasian and Titus for a temple goes far beyond the single colossal statue of Domitian that survives there from his reign. After he died in disgrace, his temple was reconsecrated to his father Vespasian, but John could not have seen that. As for placing him at Aphrodisias in the great edifice of the city’s emperor cult, he might conceivably have gone there from Laodicea (also in modern Turkey), which was the home of one of the seven churches of Asia, or he might have been curious to visit the Jews of Aphrodisias, but there is simply no trace of such a visit. John’s reference to the throne of Satan does indeed suggest that he had been to Pergamum, but Aphrodisias was by no means nearby, as Pagels says it is.

John’s twofold reference in Revelation to a “synagogue of Satan” might, however, reflect personal experience of the Jewish communities in Asia Minor. The two cities to which he assigns his satanic synagogues are Smyrna and Philadelphia, in both of which Jews were living. John unambiguously denounces persons “who say that they are Jews and are not.” In the second passage where he condemns these people John goes on to say that they are liars. Despite such clarity in a work that is distinguished by its obscurity, commentators have lavished exceptional ingenuity on these two references. Some have even tried indefensibly to make John say the opposite of what he actually says, as Pagels points out, by claiming that John is referring to “Jews who don’t deserve to be called by that name.” But these delinquents must have been either gentile Christians passing themselves off as Jews or pagans claiming to be Jews. Jewish Christians could hardly have been called liars for saying that they were Jews.

Advertisement

The false Jews to whom John refers can only have been gentiles, i.e., people who were not of Jewish origin, and for John what made their synagogues satanic was their dishonesty. Yet such conduct would be readily conceivable at a time in which the Roman state was persecuting Christians. A synagogue could be a safe refuge for frightened gentiles, and there they might even have found Jews who had converted to Christ. A synagogue offered hope for Christians of an escape from the persecution that Nero had so viciously inaugurated.

John’s indignation over the poseurs in the two synagogues of Satan would fit well with his own Jewish ethnicity. Already in antiquity Dionysius of Alexandria had discerned that the Greek of the Apocalypse reflected the “barbaric” (non-Greek) language of the writer, presumably Aramaic. The oddities of his Greek do not of course cast any doubt on his commitment to Christ, but they mirror the fundamentally Jewish background of his thought and expression. They also make it most unlikely that he was the author of the Gospel of John, whose author was arguably the most hellenized and subtle of the evangelists. As Pagels observes, “critical readers” have pointed out that “the two books diverge sharply in language and style.”

Just about the only chronological indicator in Revelation on which most interpreters agree is the mystic number of the beast that appears from the earth in succession to a fearful creature from the sea with seven heads and ten crowned horns. Both beasts represent the enemies of John and his religion. The seven heads represent seven kings, “of whom five have fallen, one is living, and the other has not yet come.” The second beast, “that was and is not,” stands for an eighth king who will remain for only a little while, and he is explicitly described as one of the seven kings. He is named by the number 666. When this number is converted into Hebrew letters, each of which can carry a numerical value, the name of the emperor Nero emerges. This is perhaps the only gloss on the text of Revelation for which there is a substantial scholarly consensus. John’s description of seven kings, of whom five have fallen, fits perfectly the five emperors from Augustus to Nero. The one who is living and the other yet to come point in turn to Galba, who reigned for six months, and to his successor Otho.

The eighth ruler, who is said to have been one of the seven, can be easily explained once 666 is seen to be Nero. Soon after his death the popularity of that emperor in the eastern Mediterranean induced several ambitious rogues to pretend to be Nero and to claim that he had not really died. Because he had liberated Greece from Roman rule and, in spite of his murderous excesses at Rome, had enjoyed a surprisingly good reputation among Greeks, even Plutarch had a good word for him. But of course Christians saw him as the hated persecutor who had nailed up and burned their coreligionists in the streets of Rome.

Accordingly, John had every reason to hate Nero. But it would have been odd, if not inconceivable, to give him such prominence more than twenty years after he died, without the slightest allegorical allusion to his successors, Vespasian and his two sons, Titus and Domitian, who loomed so large in both Jewish and Christian communities after Nero’s death. It was perhaps inevitable for Christians to look for an emperor under whom John might himself have suffered, and banishment would serve as a good explanation of his hostility toward Rome.

Domitian, who was universally judged to have been an evil emperor and widely believed to have been another persecutor, would have been an ideal candidate for obloquy in a period in which most of the gospels were probably being written. But John says nothing whatever to support the idea that Domitian exiled him or even that he was writing toward the end of his reign. He says nothing explicit about the cities of Asia Minor in his own day apart from the scathing reference to the Pergamum Altar, which had already been standing for centuries, and to the two synagogues of Satan. The gentiles in those synagogues would have outraged a Jewish Christian, which John certainly was, but their presence also reflects a society before Jews and Christians parted company and went their separate ways, to become, as they soon did, bitter enemies. For a brief moment both Jewish and gentile Christians faced a common threat.

The Jewishness of the Book of Revelation was a central point in John Marshall’s book, and it is now even more prominent in Daniel Boyarin’s new work, to which he has given the provocative title The Jewish Gospels, in an unmistakable homage to Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels.2 But it would be a big step from the Jewishness of Revelation to the Jewishness of the gospels, and one that would call for a different review and elicit considerable discussion. Yet Marshall and Boyarin are united in their reading of the Apocalypse, which cannot be considered a gospel on any interpretation. Particularly telling is Boyarin’s emphasis on the connection, which Pagels also discusses, between John’s vision in the New Testament and the vision of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible.

The closest parallel comes in Daniel’s evocation, in chapter 7, of four great beasts that came out of the sea, which Pagels assumes, like many others, to represent Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome. He saw someone in heaven who looked like a man (“Son of Man” in the original text) approaching the Ancient of Days, and this man received dominion over all peoples and nations. In reading chapter 7 of Daniel, which is written in Aramaic, John knew perfectly well that “Son of Man” was a normal Aramaic locution for a human being, and he was, as a Christian, receptive to understanding Daniel’s vision as a prophecy of the coming of Christ. He appears to have refashioned the four great beasts into the beast with seven heads and ten horns so as to accommodate the altered world of the Roman Empire.

When or whether Judaism and Christianity parted from each other is a subject of endless debate. Pagels declares:

Christian scholars have long taken for granted the commonplace—most often unspoken—assumption that “Judaism” as a living, ongoing, and powerful tradition, effectively came to an end around 70 CE, when the Jerusalem Temple was destroyed.

This may be an unspoken assumption in some quarters, but it is hardly commonplace and overlooks the Judaism that provoked two revolts in the early second century, including the cataclysmic uprising of Bar Kokhba under Hadrian, to say nothing of the rabbinic schools in Palestine under the Roman Empire.

Some believe that Jesus’ injunction against Jewish dietary laws marked the beginning of the separation of Christians and Jews. But Boyarin denies this and even argues provocatively that Jesus kept kosher. Undoubtedly over time Jews who became Christians gave up restrictions on eating as well as the practice of circumcision, which Paul famously repudiated. Pagels recognizes that John’s Revelation seems to span the great divide. In the century after him the incompatibility of Jews and Christians grew into overt hostility on both sides, and early Christian attacks on Jews resemble what would be called anti-Semitism today.

A benevolent instinct that has arisen and spread in recent years has called into question the whole idea of “a parting of the ways” and tried to reinterpret the plainly intolerant narratives of many Christian texts. In going to his martyrdom at Smyrna in the second century Polycarp is said to have observed the Jews of the city zealously helping its Roman citizens by adding wood to the pyre on which he would be burned alive, and they did this “as they habitually did.” A century later another martyr, Pionius, reportedly commented on the enthusiasm with which the Jews of the city saw its Christians persecuted and killed: “Even if we are their enemies, as they say, we are human beings.” The Christian texts become increasingly shrill, not least in the anti-Jewish harangues of John Chrysostom in the fourth century. In an account of Jewish pogroms against Christians in the sixth century the Byzantine emperor Justin appealed for an expedition “by land and by sea against the abominable and criminal Jew.” These are terrible texts, but they cannot be washed away, and they show how far Christianity had departed from its Jewish roots.3

The separation is less prominent in the Jewish rabbinic tradition, but polemic against the New Testament’s account of Jesus appears overtly in the Babylonian Talmud, written between the third and fifth centuries. This seems to have provided the background for a viciously anti-Christian narrative in the medieval biography of Jesus known as Toledot Yeshu. Peter Schäfer, the author of Jesus in the Talmud, has asked why the Babylonian Talmud, which is a product of Sassanian Persia, should have included strongly negative comments on Jesus—particularly his virgin birth and his resurrection, both of which are mocked and satirized, whereas there is nothing comparable in the Palestinian Talmud.4 The relatively peaceful coexistence of the rabbis in Galilee and the neighboring Christian communities in late antiquity seems to provide the answer.

By contrast, the conditions in Zoroastrian Persia were considerably more unstable for Jews and Christians alike and, Schäfer suggests, may have led to a greater hostility between them:

Jews and Christians are, together with the other heresies, on an equal footing as far as the chief magian’s wrath [i.e., the wrath of the chief Zoroastrian priest or magus] is concerned, with no difference whatsoever.

But, Schäfer continues, “the Christians were much worse off than the Jews” because Persia’s great rival, the Byzantine Empire, was a Christian state, and this put all Sassanian Christians at risk. Outside Persia the Sassanians often supported Jews as a means of countering Byzantine influence, and that is why the Jews welcomed them when they captured Jerusalem in 614.

In looking beyond the era of John’s Revelation, whether that was in 69 or 90, Pagels moves forward into texts that belong, like the martyrdoms of Polycarp and Pionius, to the period when Christianity and Judaism had not only separated but, at least in parts of the Roman Empire, become fierce antagonists. What diluted their hostility was the increasing dissension among Christians themselves. Heresies bloomed so luxuriantly that certain early Church Fathers, such as Irenaeus in the second century and Epiphanius in the fourth, could scarcely denounce them all. It was in the midst of these aberrant movements that the gnostic texts were written, and their apocalyptic character not only reflects the popularity of John’s visions but the visions that had inspired him. Until the discovery of the so-called Gnostic Gospels we lacked any notion of the inventiveness and extravagant rhetoric of these documents. Some of them proclaim that their content was secret and confined to a select few, and one of these was even a Secret Revelation of John.

So it is perhaps not surprising that the fundamental Christian Apocalypse, which now concludes the New Testament, had a difficult passage through all the other apocalypses in order to achieve the canonical status it enjoys today. When a major heretical movement arose in Asia Minor in the second century and eventually spread as far as Gaul and Africa, it invoked above all the Revelation of John. The message of this movement was “The New Prophecy,” as promoted by its leader, Montanus.

To counter this movement, one of its most vocal opponents even denied that Revelation was the work of John and ascribed it instead to a nonentity called Cerinthus. The book was solemnly condemned at a church council after Constantine had made the Roman Empire Christian. Although by then it had long been in circulation, only when Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria and the leading theologian of orthodoxy, listed the book in his canonical New Testament in the fourth century did it begin to settle into the place where it is found today, but not without further controversy.

Pagels ends her account of Revelation with Athanasius and the closing of the New Testament canon. As she observes, the horrors of violence, warfare, and celestial convulsions in John’s book give way at the end to a radiant and comforting vision of a new heaven and a new earth, including the descent of the new Jerusalem. Strenuous efforts on the part of Athanasius’ successors ensured that henceforth this would be the only apocalyptic narrative that Christians would be able to read.

Although the accidental discovery at Nag Hammadi in 1945 nullified the ancient ban on these texts, John’s vision has retained its power and primacy among Christian apocalyptic books. After nearly two millennia its meaning and the identity of its author continue to provoke lively debate. There is still no consensus about the time when it was written, or even whether it might be a composite work of miscellaneous bits written at different times. All this demonstrates how irresistible, even indispensable Revelation remains for those who try to understand early Christianity in the years when it was breaking apart from its Jewish origins. Even with all the other revelations about which Elaine Pagels knows so much, there is nothing quite like it.

This Issue

April 5, 2012

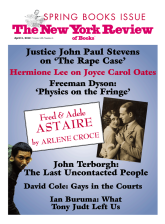

They’re the Top

We’re So Exceptional

Who Is Peter Pan?

-

1

Parables of War: Reading John’s Jewish Apocalypse (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001). ↩

-

2

The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ (New Press, 2011). ↩

-

3

For examples of revisionist views see The Ways That Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, edited by Adam H. Becker and Annette Yoshiko Reed (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003). ↩

-

4

Jesus in the Talmud (Princeton University Press, 2007), pp. 115–122. ↩