Born in 1860, third of five brothers and one sister, in Taganrog, a port on the northeastern tip of the Sea of Azov, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was left to fend for himself in 1876 when his father, a grocer, fled to Moscow to escape imprisonment for debt. Anton remained alone in Taganrog to complete his schooling, paying for room and board by giving private lessons and rejoining the family in Moscow in 1879, when he found them living in poverty in a damp basement. From then until his early death from tuberculosis in 1904, Chekhov would never be away from them for so long, particularly his mother and younger sister Maria. While his elder brothers, Alexander, a writer, and Nikolai, an artist, moved out and married, Anton stayed at home, rapidly becoming both the breadwinner and the darling of the family. The decision to seek an income writing short stories was part of that transformation: the money would tide the family over until he could complete his degree in medicine and practice a profession.

Chekhov’s grandfather, a serf, had worked hard to buy the family’s freedom from bonded labor, and Chekhov’s father, whose main interest was church choral music, had plunged his family into poverty; now Chekhov would raise its members to genteel society, eventually buying and building country houses where his parents and his young brothers and his sister could live together, while paying for Maria to study to become a teacher. She kept a portrait of Anton in her bedroom and frequently worked as his secretary; he discouraged her from marrying. The youngest brother, Mikhail, was given the task of pestering publishers till they paid up Anton’s royalties. In Memories of Chekhov (a compendium of firsthand accounts of meetings with the author), the future painter Zakhar Pichugin recounts a visit to the family when Anton was just twenty-three:

As I came in, I greeted the father of Anton Pavlovich, and heard in reply the words which he whispered in a mysterious tone.

“Hush, please don’t make noise, Anton is working!”

“Yes, dear, our Anton is working,” Evgenia Yakovlevna the mother added, making a gesture indicating the door of his room. I went further. Maria Pavlovna, his sister, told me in a subdued voice,

“Anton is working now.”

In the next room, in a low voice, Nikolai Pavlovich told me,

“Hello, my dear friend. You know, Anton is working now,” he whispered, trying not to be loud. Everyone was afraid to break the silence….

In 1886 Chekhov published a story, “Hush,” in which a writer demands silence from his family but doesn’t respect their need for sleep; Anton, it seems, used to wake his sister Maria to discuss his ideas. Aside from the fact that in the story the selfish writer is a mediocre journalist, the crucial difference between author and fictional character is that the latter’s family is made up of a wife and small children who are portrayed as defenseless victims. Chekhov avoided such ties and usually described relationships between fathers and sons in negative ways, as if it were impossible to occupy a position of authority without abusing it; throughout his life he never stopped mentioning that he had been beaten by his father.

In view of the reverence that his first literary successes inspired in his family, together with his ease in producing and publishing stories (528 between 1880 and 1888), it was never likely that medicine would become Chekhov’s main profession. But he did practice, first in provincial hospitals and later, out of generosity, when he treated peasants near the 575-acre estate he bought in his early thirties at Melikhovo, some forty miles south of Moscow. Chekhov would raise a flag to let people know he was at home, then find himself overwhelmed with requests for help. In Anton Chekhov: A Brother’s Memoir, Mikhail recounts an anecdote that suggests the tension between involvement and withdrawal characteristic of so much of Chekhov’s life. It was 1884 and he was treating a mother and three daughters for typhoid:

Anton…spent hours and hours with those patients, exhausting himself. Despite his efforts, the women’s condition worsened until one day the mother and one of the sisters died. In agony, the dying sister grabbed Anton’s hand just before she passed away. Her cold handshake instilled such feelings of helplessness and guilt in Anton that he contemplated abandoning medicine altogether. And indeed, after this case he gradually switched the focus of his energies to literature….

Neither Memories of Chekhov nor Mikhail Chekhov’s charming memoir can replace the full-scale biographies of the author by Ronald Hingley and Donald Rayfield, but they offer a strong sense of the milieu in which Chekhov lived and the curious way he positioned himself in relation to friends, family, and reading public. All those who met Chekhov spoke of his accessibility and charm, his willingness to read manuscripts by aspiring authors or to hurry to the bedside of an acquaintance in need. Some, however, noted a reserve behind the charm (“as if he was wearing iron armor,” remarks writer Ignaty Potapenko) and his habit of contributing to conversations only with rare wry remarks or alternatively a constant stream of decidedly unserious jokes.

Advertisement

Above all, there was his tendency to disappear without warning; Potapenko recalls how Chekhov once cut short a visit to Moscow immediately on arrival because a garrulous acquaintance had grabbed him as he got out of his cab and “promised” to spend the evening with him. Chekhov was too polite to say no, Potapenko observes: “he didn’t have the ability of hurting another person.” Alexander Serebrov-Tikhonov, who went fishing with the author, remembers him explaining his love of the sport with the remark that while fishing “you are not a danger to anyone.”

If in company Chekhov often felt trapped, once alone boredom and feelings of exclusion became equally oppressive: “Despite its unquestionable loveliness, this place is my prison,” he said of his house in Yalta. “Freedom complete and absolute, freedom” was the supreme value, something the author never tired of repeating, but where did it lie? Not satisfied with oscillating between a hectic, hard-drinking social life in Moscow and periods of relative quiet in the country, Chekhov eventually looked for more idiosyncratic arrangements: in Melikhovo he had a small study built away from the main house so that he could invite as many guests as possible, then escape from them to be alone; when he built the house in Yalta he also purchased a secluded cottage on the coast nearby “so that I could have some solitude.”

These solutions depended on the willingness of Chekhov’s family to entertain Anton’s friends while he absconded: his mother and Maria became famous for their abundant cooking. In his memoir, his brother Mikhail takes evident pleasure in naming the famous guests he got to know while they waited for Anton to emerge from his hideout. None of this careful social engineering, however, could resolve the question of what the author was to do about women and marriage.

Published mainly in small and far from prestigious newspapers and reviews, initially written under a pseudonym so as not to compromise his medical career, Chekhov’s early stories are wonderfully light and short. In “A Blunder,” two anxious parents eavesdrop on their daughter and a writing teacher; as soon as the young man makes an amorous move toward the girl, they will rush in with an icon and bless the couple, after which it will be impossible for the teacher to escape marriage. The couple flirt, the girl offers her hand to be kissed, the parents hurry in and shout their blessing. But in her haste the mother has picked up not the icon, but the portrait of a writer. There are shouts and recriminations. Chekhov closes his story with the memorable line: “The writing master took advantage of the general confusion and slipped away.”

In all these stories the decision to love is always an error leading to a prison, whether in marriage or an affair, from which there is no safe escape; yet love is powerfully seductive and life a prison of boredom without it. In “A Misfortune,” a principled wife resists the approaches of a passionate young lawyer and urges her husband to wake up to what is going on; but eventually she succumbs as, “like a boa-constrictor,” desire “gripped her limbs and her soul.” In “Champagne,” a railway station master marooned in a loveless marriage in a remote village argues with his wife as they drink champagne on New Year’s Eve. The wife predicts bad luck because he has dropped the champagne bottle, but rushing out of the house in a rage he reflects, “What further harm can be done to a fish after it has been caught, roasted, and served up with sauce at table?” Returning home, he finds the answer to his question; a train has brought his wife’s very young aunt:

A little woman with large black eyes was sitting at the table…. The grey walls, the rough ottoman, everything down to the least grain of dust seemed to have become younger and gayer in the presence of this fresh young being, exhaling some strange perfume, beautiful and depraved.

The temptation is irresistible. A few lines and months later, such is Chekhov’s dispatch, we discover that our narrator no longer has either wife, job, home, or lover.

Advertisement

At first glance extremely varied, Chekhov’s stories always have at their core a situation in which the object of desire, or the very fact of desiring, turns out to be toxic or imprisoning, and it is this that gives them their characteristic aura of enigma and pessimism. “Grisha” is written from the point of view of an excited two-year-old; taken out in the street by his nurse, he is left so “shattered by the impressions of the new life” that he needs “a spoonful of castor-oil from mamma.” In “Agatha,” the narrator goes fishing at night with Savka, a handsome young man who lives in complete idleness, relying on the gifts of the peasant women who are infatuated with him. The fishing is interrupted by the arrival of Agatha, a wife risking her marriage to come and make love to Savka, who despises women but is unable to resist them, even at the cost of a beating from their husbands. While the two make love the narrator, fascinated and appalled, falls asleep over his fishing rod.

As pressure for social and political reform intensified in Russia through the nineteenth century, the peasants became the focus of much debate. From a peasant background himself, Chekhov was well placed to have his say, especially when, in 1888, his work broke into the more serious journals in St. Petersburg. But declaring himself “neither liberal, or conservative,” the author refused to be tied to any political position, and in his stories peasant life is subsumed into the underlying tension that galvanizes all his narratives: vital, impulsive, and always ready for love and action, Chekhov’s peasants can’t fail to fascinate; at the same time they are ignorant, dirty, inaccessible, and dangerous.

“The Robbers” is a strong example of Chekhov playing off sexual attraction against class prejudice to create this ambivalent view. A doctor’s assistant, Ergunov, loses his way in a snowstorm while bringing medical supplies to a hospital on his superior’s best horse. Taking refuge in an inn, he finds himself in the company of Liubka, the innkeeper’s beautiful twenty-year-old daughter, Kalashnikov, “a notorious ruffian and horse thief,” and Merik, a “dark peasant” with “hair, eyebrows, and eyes…black as coal.” Intimidated but assured of his social superiority, the doctor shows the men his gun. All the same, he is sexually excited by Liubka and feels left out when the men won’t let him join their bragging at dinner. When Kalashnikov plays his balalaika and Merik and Liubka dance, Ergunov “wished he were a peasant instead of a doctor.” Hurrying out into the snowstorm when Kalashnikov leaves to check that his horse isn’t stolen, he finds that even nature is in tension between freedom and imprisonment:

What a wind there was! The naked birches and cherry-trees, unable to resist its rough caresses, bent to the ground and moaned: “For what sins, O Lord, has thou fastened us to the earth, and why may we not fly away free?”

Eventually, Liubka, who evidently has some kind of relationship with Merik, kisses the doctor while Merik steals his horse; then she punches him in the face when he tries to make love to her. The following morning, however, rather than feeling angry about the horse, Ergunov is drawn to the free life he imagines the peasants leading, to the point that he feels that if he were not “a thief and a ruffian…it was only because he did not know how to be one….”

Published in 1890, “The Robbers” was written as Chekhov was facing a major life crisis. Throughout his twenties he had alternated winters in Moscow with summers in rented country houses, working all the time. His prose had been recognized at the highest level with the award of the Pushkin Prize in 1887, and his play Ivanov was well received in 1889. None of this brought contentment; on the contrary, Chekhov felt so exasperated with the literary world that he was talking about abandoning writing for medicine. In the spring of 1889 his elder brother Nikolai died of tuberculosis. Chekhov himself had been spitting blood for years and though he refused to be examined by a doctor and never discussed his health, he must have known what it meant.

In the months following this bereavement he wrote “A Dreary Story,” in which an aging professor of medicine faces his forthcoming death in a mood of restlessness and irritation. His wife, once desired, is now plain and pestering, his emotionally needy daughter provokes only a sense of helplessness, and his beautiful young ward, Katya, a failed actress, both attracts and repels him. The doctor would like to feel close to his family and friends, but they are inferior and demanding. Having refused to help Katya when she begs for advice, he suffers at the thought that she will not come to his funeral. Remarkable as ever in Chekhov is the way a rapidly delivered and apparently straightforward narrative creates an atmosphere of profound and inexplicable psychological malaise.

As he wrote this story, the eminent and handsome Chekhov was surrounded by young women eager to make a life with him. Telling friends he was in a hurry to marry, he nevertheless withdrew from every flirtation and brief affair. For a while it seemed that the brilliant Lika Mizinova, ten years his junior (“Lika the Beautiful,” Chekhov called her), might be the one. She was in love and his flirting was frenetic. Yet Chekhov’s response to this combination of literary success, bereavement, and romantic possibility was to run away: in the spring of 1890, he departed, alone, to visit the penal colony of Sakhalin Island, off the east coast of Siberia, a three-month journey over five thousand miles of difficult terrain with no railway and poor roads.

On arrival he spent three months carrying out a census of the entire convict population of about ten thousand, interviewing over 160 people a day, preparing a file card for each, and taking notes on forced labor, child prostitution, and floggings. The return journey was made by boat to Odessa via Ceylon where the author had sex, he boasted, with “a black-eyed Indian girl…in a coconut grove on a moonlit night.” Back in Moscow he wrote: “I can say this: I’ve lived, I’ve done enough! I’ve been in the hell of Sakhalin and in the paradise of Ceylon.” Ergo, he was no longer obliged to think of marrying.

Little is said about Sakhalin in the two books under review, and even the larger biographies limit themselves to documenting the grim conditions of the penal colony and Chekhov’s bizarre one-man census. Yet the trip to Sakhalin gives an insight into Chekhov’s writing as well as marking a turning point in the way he handled personal dilemmas. Determined to stay free, he fled to contemplate those in the worst prison imaginable. Attracted and repulsed by life’s teeming vulgarity, he tried to put order into the most degraded of communities. What were his six hundred plus stories if not, in their fashion, a census of prisoners, of people falling into traps of love, work, obsession? After Sakhalin, Chekhov’s stories are fewer and bleaker. One of the first, “Ward No. 6,” tells the story of a lazy hospital doctor fascinated by a mental patient whose obsession that he would be arrested and imprisoned became self-fulfilling when he was certified as mad. The same fate befalls the doctor, whose excessive interest in the patient is interpreted as insanity.

Despite continued to-ing and fro-ing between Moscow and the country, the years from 1892 to 1898 were the most stable of Chekhov’s life. He bought the estate in Melikhovo, put his family to work to rebuild and farm it, saw and avoided huge numbers of guests, and began a new activity as a philanthropist, helping the local authorities organize famine relief and sponsoring the building of schools for peasant children. To become less dangerous and ensnaring, life must be educated and organized. Many of the conversations in Memories of Chekhov have the author deeply pessimistic about the present but surprisingly optimistic about a wonderful future hundreds of years hence when man will use science to turn the world into a beautiful garden.

It would have been logical at this point in Chekhov’s career for him to write a novel. The most revered Russian authors were novelists. Publishers and critics expected it. In the early days he had managed one ninety-page pastiche of the Hungarian romantic novelist Jokai Mor, and an elaborate 180-page murder melodrama, The Shooting Party, whose narrator turns out to be the murderer. But this was little more than juvenilia. Feeling the pressure to perform, in 1889 Chekhov had spoken of having a novel in preparation, but after months of work he decided to break it down into a series of interrelated short stories, Tales of Lives from My Friends, which in the end was never published.

It was part of his manner and message to create a complex dramatic situation, then bow out very swiftly, leaving the reader with the impression of having witnessed a deft conjuring trick: something profound and exciting has been hinted at, then mysteriously withdrawn, without our quite understanding what it was or why it was destined not to be. In any event, the stories do not gain with greater length: the fascination and fear of life’s unruliness come across in the way circumstances are rapidly but also tersely described, with appetite, but never excess. The long novel, like marriage, would have been too great a commitment; Chekhov preferred flirtation and an atmosphere of fugitive brevity. Cut, cut, cut, was the advice he constantly gave authors who sent him their manuscripts.

Instead he began to concentrate on plays: The Seagull (1896), Uncle Vanya (1899), The Three Sisters (1901), and The Cherry Orchard (1904). More fragmented and elusive than the stories, they are hard to summarize; major speeches and rare moments of action are half submerged in casual chatter and noises heard from offstage, some of them quite inexplicable. Nevertheless, the pattern is clear enough: over four acts, often with a considerable lapse of time between each one, a dozen or so characters dig themselves deeper and deeper into life’s mire. In love in act one, they are married and regretting it in act two; if they long to enter the workplace when we first see them, they are bored to death with it a few years on. Their love unrequited, they marry someone who loves them, just to have something happen, and invariably end up hating their spouse. Inadequate to the challenges of extended relationships, what talents they have remain peripheral to the action.

Chekhov called the plays farces; his director, Konstantin Stanislavsky, saw them as lyrical tragedies. The two argued. But the genius of these dramas is never quite to declare themselves as one thing or the other. Speech by speech, it is impossible to know what level or category of seriousness to attribute to them; they make sense insofar as they challenge our habits of making sense.

In 1897 a lung hemorrhage marked the beginning of the end. Chekhov sold Melikhovo and moved the family to Yalta for the better climate. No longer something he could deny, disease exacerbated his old dilemma: with little time left him, it was even more important to live intensely; yet intensity fed the disease and shortened life expectancy. In 1899 Chekhov arranged for his prose work, previously divided between numerous magazines, to be issued by one publisher. The time for hedging bets was over. “Then suddenly, in late May of 1901,” writes Mikhail, “I read in the papers that Anton had gotten married…. I did not even know who his bride was.” Mikhail’s bitterness was as nothing to the anguish of their sister, Maria, who, having kept Anton close company for so many years, felt deeply betrayed.

The bride, Olga Knipper, was the Moscow Art Theater’s leading actress, a woman at the heart of Russian life and society. Chekhov insisted they marry in secret; he feared being devoured by the public. “For him, this will be like committing suicide or being sent to prison,” the writer Ivan Bunin remembers thinking. But since Olga would go on working in Moscow and Chekhov, for his health, was obliged to live in Yalta, it was never likely they would spend much time together. A friend and doctor, Isaac Altshuller, recalls that on returning to Yalta from trips to Moscow, Chekhov “would be suffering from serious throat bleeding, or coughing fits.” At play rehearsals he became so excited that the actors had to ask him to leave. Recriminations and reconciliations with Olga over their difficulties being together were interminable. Yet she was beside him at the end. Having spoken, in April 1904, of going to the Russian-Japanese war as a doctor, to get a view of the action, Chekhov in fact went to seek treatment in the German spa town of Badenweiler where, only forty-four years old, he died in his hotel room shortly after midnight on July 15.

Mikhail’s account of the funeral describes a huge crowd that pressed “into the cemetery, crushing crosses, pushing monuments, breaking fences, and trampling flowers.” Gorky, whose writing Chekhov criticized for its excessive exuberance, understood the irony: Anton “fought his whole life against vulgarity,” he remarked, yet his funeral was “a huge mess of noisy, crowded and vulgar men and women.” Arguably, Chekhov, in his coffin, was well placed: he had alway s liked to be near crowds, but never quite among them.

This Issue

April 5, 2012

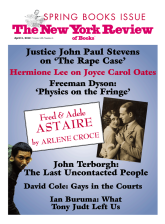

They’re the Top

We’re So Exceptional

Who Is Peter Pan?