In response to:

An Exclusive Corner of Hebron from the February 23, 2012 issue

To the Editors:

Jonathan Freedland captures the vibrancy of Arab Hebron [“An Exclusive Corner of Hebron,” NYR, February 23], with “its thronging market square” that “brims with life and trade” for 175,000 Arab residents. But he seems greatly troubled by the presence of seven hundred Jews, confined to 3 percent of the city, who require the constant presence of Israeli soldiers to protect them from their hostile neighbors.

Freedland’s discomfort in the tiny Jewish Quarter is palpable. Understandably so, since his “proud Israeli” guide Yehuda [Shaul] is affiliated with Breaking the Silence, an organization founded to gather and publicize testimony from soldiers who vigorously oppose a Jewish presence in Hebron.

Touring the tiny Jewish Quarter the “most shocking” images that Freedland encounters are Stars of David painted on the walls of abandoned Arab shops. Nothing is said about the refusal of the Israeli government to permit Hebron Jews to inhabit abandoned Jewish property or purchase property from willing Arab sellers. He notices a plaque—“a seal of government approval”—on a building inhabited by six Jewish families. But he seems unaware that it commemorates six Jews who were murdered by Arab terrorists as they returned from prayer to celebrate the Jewish Sabbath.

A holy city to Jews for three thousand years, Hebron is where the burial tombs of their patriarchs and matriarchs are located, beneath the splendid stone edifice built by King Herod. Muslims (not, as Freedland writes, “Mameluke, Ottoman, British, and Jordanian rulers”) barred Jews from entry for seven centuries. In 1967, nearly four decades after a horrific Arab pogrom destroyed their community, Jews returned to Hebron.

Freedland embraces Yehuda’s depiction of Hebron as “an intense, distilled version of the wider Israeli occupation.” Hebron can better be understood as the fulfillment of Zionism in the city that rivals Jerusalem in its ancient Jewish sanctity.

Jerold S. Auerbach

Author of Hebron Jews: Memory and Conflict in the Land of Israel

(Rowman and Littlefield, 2009)

Jonathan Freedland replies:

Jerold Auerbach suggests I am troubled by the presence of Jews in Hebron, further attributing that position to Yehuda Shaul and Breaking the Silence. But Shaul is clear that his opposition is not to Jews living in that city, but rather to the apparatus of occupation that sustains their presence. “It’s not about who lives there,” he told me, “but about what system applies there.” As for Breaking the Silence itself, Auerbach’s description is not accurate. The group was founded by IDF veterans to gather testimony from fellow Israeli soldiers who, like them, had served in the occupied territories. It describes its aim succinctly as “to expose the Israeli public to the reality of everyday life” in those territories.

The piece was not an exploration of my views but, for what they’re worth, I see no reason why, in principle at least, a two-state future should not allow Jewish communities to live in Palestine just as Arab communities now live in Israel. The issue, then, is not the Jewish presence in Hebron but rather the Israeli occupation of the city and its impact.

Auerbach says that the Hebron Jews—who are estimated by the IDF to number 800 to 850—are “confined to 3 percent” of the city. In fact, the Israeli-controlled H2 district accounts for 20 percent of Hebron and there is no formal prohibition on Jewish movement around those parts, save for the Casbah, which, as I reported, is a closed military zone and therefore off-limits—though even that area is accessible to Jews for a few hours on the Sabbath. What’s more, the 3 percent Auerbach refers to is not just any 3 percent, but the heart of historic Hebron, now out of reach of Palestinian Hebronites.

He is right that Jewish purchase of Arab land in the West Bank requires official Israeli permission, a mechanism to allow consideration of the political and security impact of any settlement activity. He is surely not calling for a policy in which all property under Israeli jurisdiction is returned to its original owners: were such a policy applied within pre-1967 Israel, for example, many Palestinians would be able to press claims to homes or villages now inhabited by Israeli Jews. That is an issue I doubt Jerold Auerbach is keen to open.

He suggests I am unaware of the murder of six yeshiva students at Beit Hadassah in 1980 and similar outrages. But the piece makes full reference to the series of terror attacks on Hebron Jews that have played a crucial part in creating the current situation. His insistence on reducing successive and different rulers of Hebron to the single category “Muslims” is revealing but inaccurate. The British were not Muslims, but they maintained the same prohibition on Jewish access to the Tomb of the Patriarchs.

Advertisement

As for the massacre of sixty-seven Jews in 1929, it might be helpful to recall that 435 Jews, over two thirds of the Jewish community in Hebron, were sheltered and saved by their Arab neighbors. As Tom Segev has written in One Palestine Complete (p. 326), “Jewish history records very few cases of a mass rescue of this dimension.”

Lastly, Auerbach sees Hebron as the fulfillment of Zionism. But if Zionism is the yearning for a Jewish, democratic state then the occupation that makes today’s Jewish presence in Hebron possible constitutes a grave threat to Zionism, endangering the two-state solution that is surely the only guarantor of an Israel that is both Jewish and democratic.

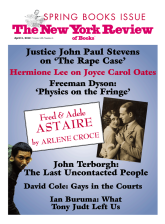

This Issue

April 5, 2012

They’re the Top

We’re So Exceptional

Who Is Peter Pan?