The title “Infinite Jest” gives only a partial clue to the exhibition of caricatures recently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose memorable quality is here recalled in a catalog of great interest. Hamlet said the words “infinite jest,” of course, in praise of Yorick, but Yorick was a jester at the court of Elsinore. That is not the same as a satirist. There may be something expansive about the very idea of jest, because it obeys no rules and draws hints from the humor of the audience.

The art of caricature, by contrast, is finite, bounded, and severe. Blake might have been speaking of caricature when he blasted the “soft” outlines of Rubens:

The Man who asserts that there is no Such Thing as Softness in art & that every thing in Art is Definite & Determinate has not been told this by Practise but by Inspiration & Vision.

A bad jest may redeem itself by having a better for its sequel. A flat or vapid or wrongheaded caricature cannot be pardoned. The province of satire is wit, and when wit goes wrong it signifies not a tactical error but a defect of mind.

The exhibition at the Met was a modest selection of the available holdings at the museum—a sampler to whet the appetite of the stroller. The handsome catalog by Constance McPhee and Nadine Orenstein is a generous record of that sample: many of the best prints are reproduced here in full-page layouts, a decent proportion in color; the sketches and plates on the half-page or in four-by-five-inch frames have been realized with unusual sharpness and delicacy.

No story about the growth of the art of caricature is extractable from the authors’ introductory essay or the 160 paragraph-long captions for the prints, but their genially informative manner captures the mood of the show. This survey hardly pretends to cover the history of a mode at once fantastic and deadpan, which was made possible by Hogarth and brought to perfection by his successors during the Napoleonic Wars. The great names of caricature—James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, Honoré-Victorin Daumier—are all present but lightly accounted for; the span takes you from the last decades of the eighteenth century to David Levine at the end of the twentieth.

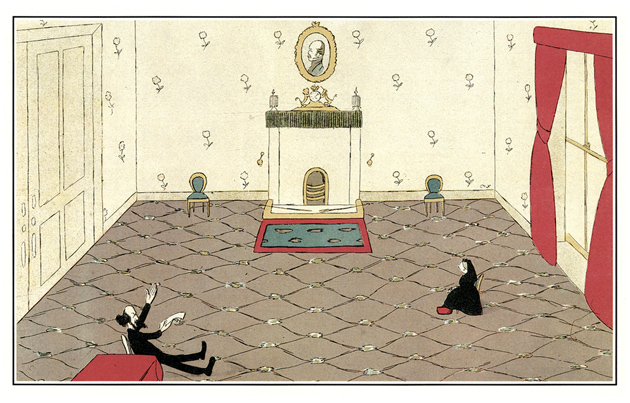

One genius of the art has been inexplicably omitted: Max Beerbohm. Yet Beerbohm’s caricatures are as inseparable from the Edwardian Age as Gillray’s are from the reign of George III and the Regency years. The victim of a Daumier or a Gillray might touch the wounded part and wonder how long it would take to heal; but Beerbohm’s models were rendered so finely and dispatched with an air so free of malice that they had no grounds for protest. His characters, from Winston Churchill to Bernard Shaw to Henry James, never knew how incurably they were themselves until he caught them. It would have made a welcome relief at the Met—between Rowlandson’s pustuled whores and the monstrous jowl of Siegfried Wolhek’s Cheney (secret papers protruding from every fold of his jacket)—to come upon Mr. Tennyson Reading “In Memoriam” to His Sovereign. Beerbohm’s print showed the poet laureate and the queen in a palace reading room that only they were formed to inhabit, Tennyson ceremonially seated but kicking up his legs with restrained enthusiasm, while Queen Victoria sits in a far chair across the room, her hands folded in her lap. Poet and sovereign are separated by a shoreless politeness.

Infinite Jest locates the beginnings of caricature, as other histories have also done, in Leonardo’s grotesques (visi monstruosi), closely followed by a Procession of Monstrous Figures by Wendel Dietterlin the Younger (1614–1669). Where Leonardo offered a view of deformed physiognomy, Dietterlin is on the track of true obscenity, with his creature-like humans and barely human creatures, drawn, as the catalog says, from the arsenal of Bosch and Breughel. A few pages on and we enter the company of artists who are successors to the prose of Swift and the poetry of Pope. They may have supposed they were working a topical sideline, but somehow they show a new expertise. They seem to have looked closely at Hogarth’s Election and A Rake’s Progress, and Marriage A-la-Mode. At the same time their palettes throw off allusions with the greatest of ease to Michelangelo and Raphael and Benjamin West.

Caricature is the most evanescent and pedantic of the visual arts. Spend an hour or two in a great collection like the Walpole Library in Farmington, Connecticut, and the surfeit of detail is exhausting: so many rich and recoverable jokes are waiting to be unlocked, yet even a reasonably informed viewer stands on the outside looking in. It takes the unearthing of controversies, month by month and often week by week, to catch the meaning of a posture or the sense of a punch line. For in the eighteenth century, the words of the visual satirist were almost as important as the image. The captions, or thought balloons, in Gillray are commonly full to overflowing, and the thoughts correspond to epigrams of the period that sound like cartoons. Thus Burke’s recollection of Marie Antoinette in her younger years—“I saw her just above the horizon, decorating and cheering the elevated sphere she just began to move in”—was brought to earth in two quick strokes of the pen by the cartoonist in William Blake: “The Queen of France just touch’d this Globe,/And the pestilence darted from her robe.”

Advertisement

The constant proximity of word and image brings a curious risk to any exhibition of cartoons. The isolation of an image can sap it of relevant meaning. Infinite Jest gives us, for example, The Nightmare, a Daumier improvisation of 1832 in which Lafayette’s sleeping frame is rudely haunted by a dream in the form of a pear sitting on his stomach: familiar shorthand, the catalog tells us, for the drooping oval figure of Louis-Philippe to whom Lafayette had “agreed to give up his republican aspirations.” Here, then, is an instance of a shape becoming a person—the sort of casual allegory on which a great deal of caricature depends.

Daumier’s cartoon seems plain enough, but arbitrary and a little flat, unless you know that it stands at three removes from its prototype: Henry Fuseli’s Gothic fantasy The Nightmare (1781). Fuseli’s erotically exposed dreaming woman, with an incubus crouched on her belly, had already received a first homage by John Boyne in The Night Mare, or, Hag Riddn Minister (1783), in which Charles James Fox, perched atop a sleeping Lord Shelburne, showers turds on his face. (Fox was the insupportable ally who, by rejecting Shelburne’s generous terms of peace with America, effectively ended the Shelburne ministry.) The same image was quarried yet again in Rowlandson’s send-up The Covent Garden Night Mare (1784), in which Fox himself lies supine, knocked out by satiety from drink and gambling, and the incubus imagined by Fuseli looks bored and put-upon. All of this baggage—unpacked with care by Diana Donald in her book The Age of Caricature*—Daumier had mastered inwardly; for him and his cleverest viewers, it thickened the comedy of Lafayette and the royal pear.

Gillray was a genius as astonishing and visionary as Blake. He worked from the outside in, but his characteristic temper, as Donald observed in her excellent study, is an “unfathomable cynicism and ambivalence.” When he draws William Pitt the Younger, who was twice prime minister between 1783 and 1806, or Edmund Burke, or Pitt’s archrival Charles James Fox (and they are always the same: Fox is a bandit, Burke is a Jesuit, Pitt is a benign but insinuating houseguest, his backbone flexible as a closet rod), Gillray captures these politicians as determined entities. They are helpless abstractions of what they were always going to be. With Gillray, the costume becomes the man, and visage and posture are the leading elements of costume. So, where Blake drew The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth (1805) and made it the terror of two continents—“that Angel who, pleased to perform the Almighty’s orders, rides on the whirlwind, directing the storms of war”—Gillray saw Pitt as an almost expressionless personage of mediocre pretensions, unusual only in his ability to carve up the world with a knife and fork.

The Plumb-Pudding in Danger;—or—State Epicures Taking un Petit Souper (1805) was a high point of the show, and it is one of Gillray’s best. You see Pitt as lean and joyless as ever, yet wonderfully potent; he holds in reserve the shrewdness of a card player and the patience of a master poisoner. As he slices the pudding of the world, with his fellow diner Napoleon, his eyes are calm and focused while Napoleon’s are popping with appetite. Poor Napoleon! His huge hunger is mounted on a tiny frame, and the red and blue feathers that sprout from his cap are as long as his legs. We are put in mind of the traits that made Pitt the longest-serving prime minister in Britain, and prompted William Hazlitt’s wonder at his power “to baffle opposition, not from strength or firmness, but from the evasive ambiguity and impalpable nature of his resistance.”

Advertisement

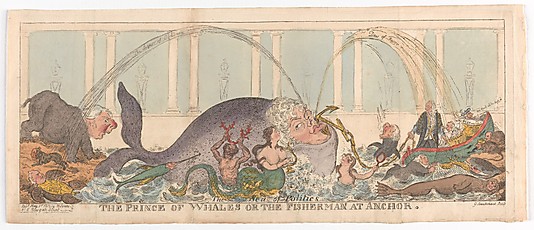

For Gillray, all politics was grotesque. He began as a Whig but was paid at last by Tories, and he made them look good, more or less. His misanthropy (anarchic, at bottom, as misanthropy tends to be) found itself checked and pushed to favor authority by an inveterate hatred of the crowd; most of all, of course, the Parisian crowd of the 1790s. Gillray’s cartoons have nearly the scope of canvases, and they imply large actions and relations, yet his individual faces are good enough to temper one’s appreciation of any other cartoonist. His influence on other artists was wide, beginning with George Cruikshank—whose Prince of Whales or the Fisherman at Anchor (1812) shows the obese prince regent (soon to become George IV) sporting among his dependents and leering at the mermaids that are his mistresses. The brilliant reproduction of a brilliant original takes up two full pages of the catalog.

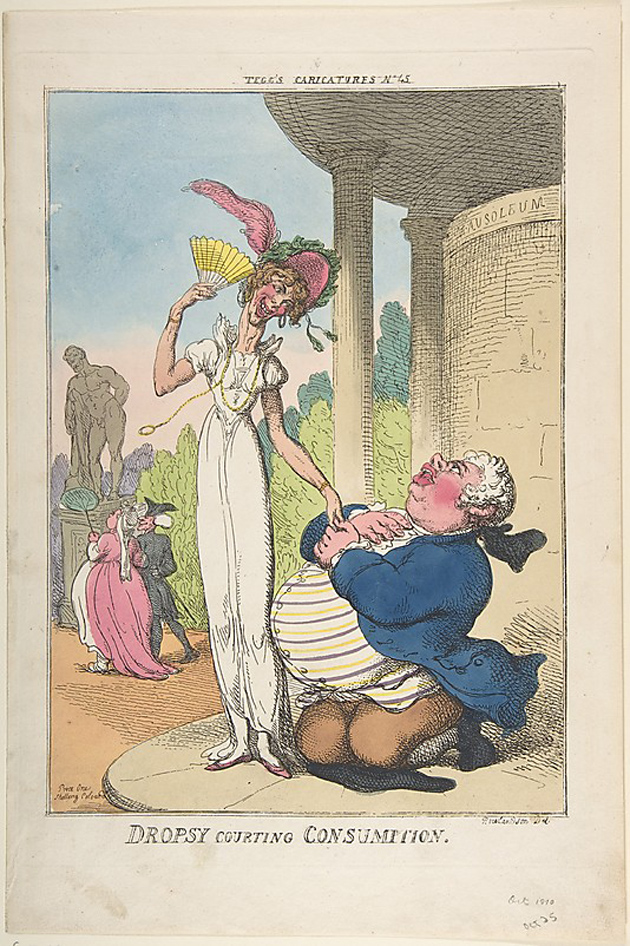

Probably Gillray’s closest competitor is Rowlandson, an artist who seems far more satisfied to be a cartoonist (see his 1792 The Hazard Room here). Rowlandson’s caricatures never struggle to be something more. Jostling masses like the crush of bodies in a Covent Garden theater gallery in Pidgeon Hole (1811; included in the catalog), or the friendly-riotous gawkers who pause to look at George III and Queen Charlotte Driving through Deptford (1785; not included), form an exception to his usual frigidity in the portrayal of diseases common to high and low society. A disgusting and well-executed piece like his 1792 Six Stages of Mending a Face—an allusion to Jonathan Swift’s repellent Progress of Beauty—shows the pox beneath the powder of a well-made-up woman of the town. A certain professionalism and continence in Rowlandson, working up vulgar conceptions to a sensible limit, betrays an aspiration with a low ceiling. Compare any of Gillray’s crammed and eventful works with Rowlandson’s 1810 Dropsy Courting Consumption and you see that for the latter the title has cued everything: rouged cheeks, unmeaning smiles, a disagreeable complicity in decay.

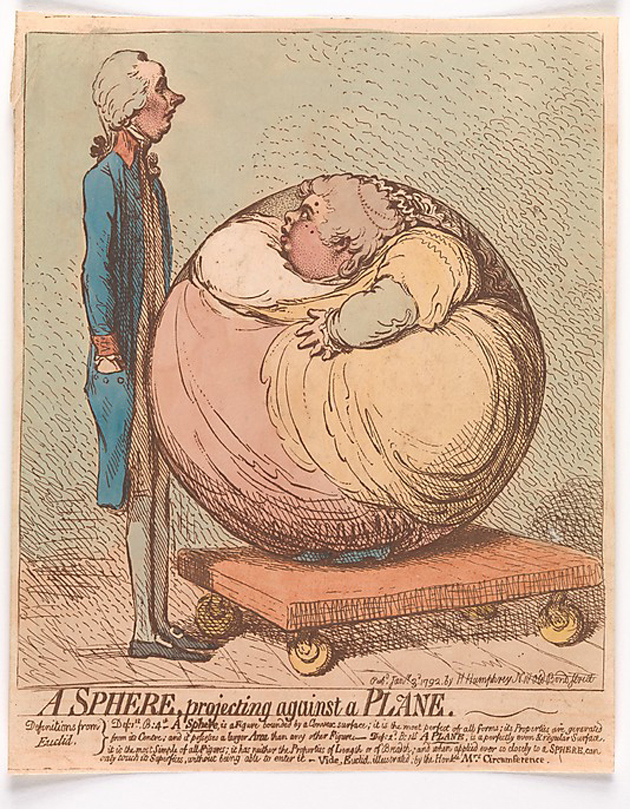

Rowlandson has no gusto and no superfluity of invention, but he can produce on demand a correct and full-bodied slander. A straight political comment like his 1784 Infant Hercules shows the toils of the serpents Fox and Lord North easily pushed away by the substantial infant Pitt. It is a bland compliment that loses almost nothing in the description. Compare Gillray’s Sphere, Projecting against a Plane (1792), which renders Pitt sharp as a fishbone beside the swollen paunch that is the Honorable Albinia Hobart, and it is no surprise to discover, later in the show, Eugène Delacroix’s admiring Studies of Four Figures, after James Gillray (circa 1817–1825). Gillray, when he went to work at caricature, took what turned out to be a permanent detour, but of all the masters of the art he was the one whose work eventually could reward study by a great painter.

The choices of Infinite Jest after the eighteenth century become haphazard. Goya’s Caprichos today are much in need of annotation: the wildness of conception and the keenness of execution take us back to the mixed mode of Dietterlin’s Procession; yet a specific but lost intention and application seem to hover just above images like the monkey serenading on a guitar a calmly seated donkey, with two shadowy figures applauding over the caption “Brabisimo!” Things get suddenly sparser in the twentieth century, and the selection from David Levine is one of his more obvious cartoons—Claes Oldenburg, drawn as his own “soft toilet,” the lid open on top of his head. A better specimen from Levine would have been his LBJ with lifted shirt, revealing the scar of a removed gallbladder in the exact shape of a map of Vietnam. The indiscreetness of the president’s gesture in front of reporters at Bethesda Naval Hospital was made to allude to his obsession with the bombing maps. A hard and deserved hit, sparer than Gillray but worthy of his piercing example—an image for the politician to carry to his grave, and with no false regrets about the speed of his departure.

-

*

Yale University Press, 1996. ↩