When the youngest man to be elected president of the United States was inaugurated in 1961, the contrast with his predecessor could hardly have been greater, and John F. Kennedy made the most of it. “Let the word go forth,” he said grandly at his inaugural, “…that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.” The Harvard graduate from Massachusetts had no great achievements to his name but he had a thick head of hair the color of chestnuts, brainy friends who played vigorous touch football, an activist international agenda, and a stylish wife with a soft voice who was already planning to bring high-end decorators and artists of international repute to the White House. Kennedy intended to move boldly where his predecessor had been watchful and slow.

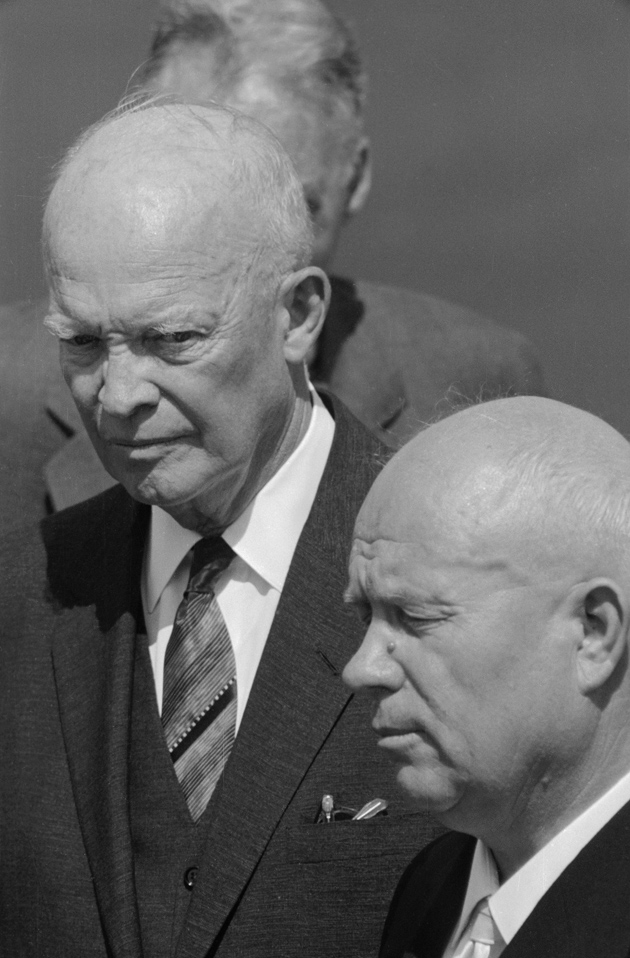

The man Kennedy replaced was seventy and none too robust. He had suffered a heart attack and a mild stroke in office, along with other ailments, and was notorious for losing himself in a tangle of words when addressing sticky questions. Dwight David Eisenhower won deathless fame as commander of the 1944 invasion of France that helped to end World War II in Europe, but once out of uniform genial blandness seemed to settle over the man, called Ike since youth. His bald pate and broad smile gave him an amiable, grandfatherly air. His tastes matched those of a generation winding down. He got up early and went to bed early. In the White House he and his wife Mamie frequently had dinner together alone in front of the TV. Ike’s favorite movie was Angels in the Outfield, a sentimental baseball film of 1951. Close seconds were the western films High Noon of 1952, in which the town marshal faces down four men come to kill him, and The Big Country, in which a retired sea captain brings peace to feuding ranch families.

Ike watched High Noon three times and The Big Country four times. In the audience at one showing of the latter was the British prime minister, Harold Macmillan, come to the US to argue for sweet reason in dealing with Khrushchev over Berlin. Macmillan hated The Big Country. “It lasted three hours!” he protested in his diary. “It was inconceivably banal.” Gregory Peck turned the other cheek for most of the film but a moment came when he had to fight. That, roughly, was what the president had been telling Macmillan all day. Macmillan was reluctant to push the Russians over Berlin; Eisenhower felt a line had to be drawn clearly before the talking could begin.

Eisenhower came by his love of westerns naturally. He considered Abilene, Kansas, his hometown, because that’s where he lived longest as a child and where he graduated from high school. “Now that town had a code,” he said at a B’nai B’rith dinner in 1953, “and I was raised as a boy to prize that code.” Rule one of the code was to confront your enemies head on, as Wild Bill Hickok, Abilene’s famed marshal of the 1870s, had done. “Read your westerns more,” Eisenhower told the diners. The code was the narrative spine of the western novels that Eisenhower read for pleasure, published by prolific romancers like Luke Short, Max Brand, and Zane Grey. At the core of every western was a man meeting a challenge with clear-eyed courage. “When I read them,” he told his wartime driver, Kay Summersby, “I don’t have to think.” With Summersby, Eisenhower had an affair that ended with the war. There was nothing complicated about it. Mamie was the woman Eisenhower had married when young. Summersby was younger, prettier, and there.

Ike’s likes were as commonplace as his taste in fiction. He was an avid golfer and by one count played almost eight hundred rounds during his eight years in the White House. His favored course was Augusta. His partners were old friends, all men, referred to as “the gang.” Ike loved to grill steaks for the gang, followed by a game of bridge. His bridge was described as about like his golf—pretty good, and on his best days maybe even a little better than pretty good. The historian William Lee Miller, in Two Americans, a new book about Eisenhower and Truman,* writes that Ike could hold his own alongside a competitive player like his friend General Alfred Gruenther. Late in life, shortly before entering the White House, he took up another hobby—oil painting. Here, too, he was content with the familiar—country landscapes and portraits of friends. Occasionally, according to his grandson David, he even borrowed his composition from a picture postcard.

The new president did not quite take Eisenhower seriously. Kennedy was amused when a poll of historians in 1962 rated Eisenhower near the low end of presidents considered average—only twenty-eighth of thirty-five. It was that embarrassing poll, Kennedy told his aide and future biographer, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., that explained Eisenhower’s return to active campaigning in the 1962 midterm elections. “Eisenhower has been going along for years,” he said, “basking in the glow of applause he has always had. Then he saw that poll and realized how he stood before the cold eye of history—way below Truman; even below Hoover.”

Advertisement

But the cold eye of history has altered its verdict on Eisenhower considerably in the last half-century, finding within the Sunday painter a man with a learned understanding, firmer than that of perhaps any other president, of the nature of the power wielded by nations—that thing, described by Thucydides, which explains why “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” Eisenhower himself would never have described what he knew in language so plain, but it is what marks the mind of the man who emerges from two new biographies. Jim Newton, in Eisenhower: The White House Years, and Jean Edward Smith, in Eisenhower in War and Peace (with twice the detail but at twice the length), both argue that Eisenhower was a figure of unusual judgment and firmness of purpose, and both record that he came by his understanding of power in two ways—first under the patient tutoring of a mentor, General Fox Conner, and then in the school of war.

Conner, a career Army officer from Mississippi, had been Pershing’s chief of operations in France during World War I. From the war he carried away two convictions—that the failure of the Allies to insist on Germany’s unconditional surrender in 1918 meant there would be a second war, and that the key to victory in the second war would be a seamless alliance hewing to the principle of unity of command. Two or more commanders were not going to run the war side by side; one would be chosen and the rest would follow. Conner preached this simple doctrine for twenty years.

Conner was a tall and handsome man, chilly and reserved, who stipulated that his diaries and letters be burned after his death. His deepest regret, like Eisenhower’s before 1942, was that he had never commanded troops in battle. But Conner had experience at the highest staff level, he was a lifelong student of military history, he took Eisenhower under his wing, and he led the younger man by easy stages through an ambitious reading program during a three-year tour in Panama.

First on Conner’s list were two novels of the Civil War, The Long Roll by Mary Johnston and The Crisis by Winston Churchill (the American novelist, not the British prime minister). Civil War novels led to Civil War memoirs—those of Grant and Sheridan. Before Conner was done with him Eisenhower had read Clausewitz’s On War three times. Simultaneously, Conner trained him in the art of writing general orders, an exercise that went far beyond the routine stuff of small-unit tactics. Later, finding a path through official obstacles, Conner wangled for Eisenhower an assignment in 1925 to the Army’s Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, where he took up golf, studied for precisely two and a half hours, five nights a week, and finished the one-year course first in his class. For the rest of his life Eisenhower believed that his rise owed more to Fox Conner than to any other man.

The education of Dwight David Eisenhower began with books—the tales of Hannibal and Caesar he loved as a child, the deeper study under Fox Conner—but more important was his experience of war, which came late. He missed the war in France. While his West Point classmates were making reputations by leading troops in combat, Eisenhower was stuck at a training camp near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The Army sent no one to tell the trainers what recruits must be prepared to face in the trenches of the Western Front. Eisenhower and his colleagues based their course of instruction partly on what they read in the newspapers, and made up the rest as they went along.

Appeals for transfer to a fighting unit came to nothing and he was still training men when the armistice was signed in November 1918. From this experience, he reported in At Ease, the last and most personal of his books, he developed “a feeling for the military potential, in human terms, of the United States.” It began with a sense of the American raw material—what men knew when they arrived, what they could tolerate physically and emotionally, how they adapted to Army life. After that the national potential was a question of arithmetic.

Advertisement

The year after the war Eisenhower gained another insight into what nations need to be strong. With a friend he attached himself to a convoy of military trucks that crossed the country from Washington to San Francisco. Jim Newton describes this grueling sixty-one-day trip in a couple of sentences; Jean Edward Smith gives it two pages, and Eisenhower himself lingers on the journey for a chapter in At Ease, mainly because he enjoyed it so much. But he noted the appalling state of the roads along the way; on some days they progressed only three or four miles. The slow pace gave him time for a good look at cities and towns he would not see again until he was running for president, and the military lesson of the grueling journey was again a matter of simple arithmetic.

From the potential of those men he had trained must be subtracted the difficulty of moving them around the country. Eisenhower didn’t forget things; in Germany at war’s end he noted the multilane highways of the Autobahn and as president he pushed through a plan for building a 41,000-mile interstate highway system, the frank purpose of which was to make America strong by encouraging commerce in time of peace and mobility in time of war.

But Eisenhower’s education commenced in earnest with World War II, and it is here that the books by Newton and Smith part company. Newton covers Eisenhower’s military career in twenty-six pages; Smith gives it full measure in 430, a bit over half of his substantial tome. Both writers seem to have been drawn to Eisenhower by earlier work. Newton’s first book, Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made (2006), focuses on a matter that Eisenhower can be said to have detested—the enforcement of court rulings requiring an end to segregation of the nation’s schools. In his earlier book, Newton credits Warren with securing a unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, and in the new book he praises Eisenhower for appointing Warren in the first place, and then for enforcing court orders by sending the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock, Arkansas. In doing this Eisenhower characteristically used more force than strictly necessary in order to settle things quickly.

What Eisenhower did as president is Newton’s subject, how he rose is Smith’s. His progress was so steady it seems fated. Days after Pearl Harbor, a friend recommended him to the Army’s Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, another protégé of Fox Conner, who believed that Marshall was uniquely suited to manage the war “because he understands it.” On Eisenhower’s first day in Washington, Marshall asked him to submit a formal plan for defense of the Philippines, where invasion by the Japanese was imminent. Eisenhower knew he was being tested, and a couple of hours later recommended a vigorous defense. Chances of defeat were high but more important was to stand by an ally, to fight, and to be seen doing both. He passed Marshall’s test, and spent the next six months in the War Department, most of it as chief of the War Plans Division.

Marshall valued Eisenhower as an officer who could get things done without constantly seeking the help of his chief. In the summer of 1942, Marshall sent him to England as the American theater commander; in July he was given command of Operation Torch, the plan to land British and American forces in North Africa, an operation complicated by the chance Vichy would fight to repel the invasion. They did, but soon quit.

In the event, Torch was a success and the Germans were expelled from North Africa. Eisenhower learned in the doing how to command an army despite several painful mistakes. But his real gift was for finding safe passage through the minefield of politics—the conflicting hopes and plans of the French, the British, and the Americans, while the Russians called continually for the opening of a second front in the West to draw away German strength. How and when to answer this call was the great strategic question of the war from the day of America’s entry. The fundamental answer was always obvious—land an army in Europe and press on into the heart of Germany until, with the Russians advancing from the East, Hitler was beaten. But where and when to invade—those variables offered infinite room for argument.

Military and civilian commanders in wartime are a prickly lot. It should be understood that Eisenhower from his arrival in Britain rarely passed a day without rejecting someone’s most cherished plan. After Torch came the invasion of Sicily, and after that a landing in Italy, followed by slow progress up the peninsula. Churchill had great hopes for the Italian campaign; Eisenhower thought it a wasteful distraction. Looming ahead all the while was the ghastly challenge of the invasion of France with its promise of a death grapple with the German Wehrmacht—an army of formidable energy, grit, efficiency, and tenacity. The Americans knew it had to be faced but in their first year of war had been too quick to think themselves ready for the task.

At one point Marshall proposed that the Allies stage a landing in 1942. Churchill flatly refused, and saved the Allies a fearful battering. But Churchill, in the event, was not ready for France in 1943, either, and offered alternative approaches and reasons for delay right up until the moment in Tehran in November 1943 when Stalin at a meeting of the Big Three insisted that Roosevelt pick a date. The president offered May 1944, later amended to June 6.

Stalin was glad to get a date but wanted something more. “Who,” he asked, “is going to command Overlord?” A week later Roosevelt told him that it would be Eisenhower. From roughly that moment until Germany’s surrender in May 1945, Eisenhower was in command of the Allied cause in the West. He gave the go order at Normandy, kept the peace among his generals, worked amicably with the difficult Charles De Gaulle, quieted the panic that followed a surprise German offensive in the Ardennes, and declined many opportunities to quarrel with the Soviets, whose titanic battles with the Germans dwarfed the war in the West. He told Churchill no repeatedly on matters close to the prime minister’s heart, and battered Germany and the German army until Hitler’s generals understood they must choose between unconditional surrender and national destruction. For eighteen months small things frequently went wrong but big things never. Eisenhower did his best to hide the wear and tear. “But underneath it all,” said Kay Summersby, “he was a very serious and lonely man who worried, worried, worried.”

Eisenhower needed a lot of persuading before he agreed to run for president. The choice of the Republican establishment in 1952 was Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, a conservative of narrow experience and rigid views of a type that has returned to dominate the Republican Party in recent years like a corpse rising from the dead. In a private meeting with Eisenhower while he was still commander of NATO, Taft told the general that he opposed NATO, was against sending American troops to Europe, and opposed any military buildup to confront the Russians or raising taxes to pay for it—in effect supporting Herbert Hoover’s notion that America might be turned into “the Gibraltar of Freedom,” while letting the rest of the world fend for itself. Taft may have finished first in his class at Harvard Law School, but Eisenhower thought him “a very stupid man [without] intellectual ability, nor any comprehension of the world.” Taft had the party, at least at the outset, but Eisenhower had the country, Taft convinced him he was needed, and he won the nomination and election.

The overwhelming question facing Eisenhower as president, as it was for every other president until the collapse of the Soviet Union, was whether the cold war would turn hot. The fact that it never did does not mean it was out of the question. The main source of danger was always misjudgment—confidence that some bold act could be taken safely, such as basing missiles in Cuba, or chasing the North Korean army right up to the Yalu River, or threatening high-handed, unilateral action if the Western allies did not leave Berlin. Once committed to a risky course of action, Soviet and American leaders both found it hard to accept the political cost of admitting error and backing off.

Actual shooting was inevitably the hardest to stop. When Eisenhower took office in 1953 he inherited a frustrating war described as a “police action” in Korea. Three choices faced the new president—a dangerous escalation, a continuing military stalemate that would bring endless political trouble at home, or a negotiated armistice. Eisenhower favored the third, but first had to bring around the Chinese and his own secretary of state, the single-minded John Foster Dulles, who believed that the United States could not agree to an armistice until the Chinese had suffered “one hell of a licking” and the Korean peninsula had been united under the government in Seoul. What Dulles wanted was the one thing Eisenhower had the experience to know was impossible—military victory without major escalation.

At a meeting of the National Security Council in April 1953, Eisenhower told Dulles no—an armistice was his goal, and once achieved he intended to abide by it. But he approached this armistice by a tortured route. In meetings with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington he said he was prepared to use nuclear weapons to end the stalemate, and, in a message passed through India, he told the Chinese the same thing. These messages were inaudible to the American public, but they were heard unmistakably by the Russians and the Chinese. What Eisenhower was saying was quite remarkably simple and clear—he would accept an armistice where the armies stood, without demanding any face-saving political concession; or he would embark on a much bigger war. Stalemate the Chinese could not have. As described by Newton and Smith, the offering of this stark choice was Eisenhower’s idea alone. No one else appeared to support it, until the Chinese signaled their tacit agreement. Smith and Newton in their separate narratives both draw the same conclusion from this episode—that Eisenhower had an understanding of war and military power shared by few other presidents, and none since World War II.

Eisenhower as president confronted similar challenges on at least four other occasions when war might have followed clumsy handling of events: in 1954 when the French sought American help to avoid defeat in Indochina, in 1956 when the Soviet Union sent an army to crush rebellion in Hungary, in 1958 when China threatened to invade the islands of Quemoy and Matsu, and in 1959 when the Russians threatened to end the four-power occupation of Berlin that had been agreed on at the end of the war. In at least three of the four cases the Joint Chiefs were not only ready to fight, but at moments even seemed to want a fight—but not over Hungary. That gave them pause.

Eisenhower’s position was the same in all four cases: he did not see the sense in a fight. To the French seeking large-scale, active intervention and to the reb- els in Budapest and their champions in Washington, Eisenhower simply said no; with the Chinese he negotiated a compromise over the islands, and a year later he managed to defuse the Berlin crisis (temporarily, as it turned out) with an offer to join Khrushchev at a summit meeting in Geneva. After defending the integrity of the Berlin agreement reached at the end of the war, Eisenhower quietly adopted Harold Macmillan’s policy of accommodation, mollifying Khrushchev with the plan to meet in Geneva. Peaceful resolutions of the crises over Berlin and Quemoy-Matsu were made possible by Eisenhower’s understanding of a basic rule governing conflict between nations—that no opponent, given time to think things over, would demand concession of something they did not have the power to take.

To deal with the challenges he faced, Eisenhower offered a measured response—refusal to give away the store, readiness to resort to force if pushed beyond a certain point, and openness to a negotiated solution when both sides were ready to accept something short of victory. Once he had decided that the point at issue was not worth a war—a matter on which he trusted his judgment—Eisenhower counted on opponents, properly invited, to reach the same conclusion. Then it was a matter of time and talking.

But Eisenhower’s caution was not the only thing rejected by his successors in the White House, beginning with Kennedy. They were equally unhappy with his policies about nuclear weapons. About their utility Eisenhower appeared to contradict himself. He added many thousands of warheads to the arsenal but then flatly claimed at a meeting of the National Security Council early in 1956 (and often repeated, as Miller notes), “Nobody can win a thermonuclear war.” Eisenhower believed that any use would lead to all-out use and a global catastrophe from which belligerents would emerge, if they emerged at all, too crippled to claim advantage.

But Eisenhower did not therefore conclude, as the Pentagon wished, that no expense should be spared to match Russian conventional forces. Eisenhower had rejected this approach as early as 1951, when he was commander of NATO. “We cannot be a modern Rome guarding the far frontiers of empire with our legions,” he said. In the opening speech of his presidential campaign a year later he said that the United States must “guard her solvency as she does her physical frontiers.” To bridge the gap between American and Soviet forces Eisenhower threatened the use of nuclear weapons against conventional attack, and he built thousands of weapons to back up threats of “massive retaliation”—the concept later reworded by Kennedy’s secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, as “mutual assured destruction.” Later presidents and their military advisers occasionally over the years tried to assert that a nuclear war could have a winner, with the right strategy, the right mix of weapons, and “enough shovels”—the phrase used by President Reagan’s war planners—to protect civilians at home. But that was theory; their practice mirrored Eisenhower’s.

Wars and preparation for war are not the only matters addressed by Newton and Smith in their books. The other controversies of the Eisenhower years—what to do about Senator Joseph McCarthy; blocking British, French, and Israeli seizure of the Suez Canal; backing up court orders to desegregate schools in Little Rock, Arkansas; Eisenhower’s chilly relations with his vice-president, Richard Nixon; the heart attack that nearly killed the president late in his first term—all get full treatment. But it is respect for Eisenhower’s handling of military matters that runs deepest—for the sure-footedness that avoided war and for the speech in which he identified an aggressive new player in American public life, known ever since by the name he gave it—“the military-industrial complex.” Eisenhower’s special gift was not for practice of the traditional military arts but for sensing the inertia of war—why it is so difficult to back away from threats of force, once issued, and almost impossible after shooting starts.

Respect for the danger of this inertia, deep enough to make a difference, seems to come only from direct personal experience. Even President Clinton’s secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, who had lived long enough to know better, thought armies could apply useful pressure. “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about,” she said once, “if we can’t use it?”

Eisenhower was surrounded by people who believed roughly the same thing, but he had learned respect for modern war as an all-or-nothing game. During his eight years in the White House he never seemed to get the big things wrong, but in the decades that have followed horrible examples abound. For all their differences, American presidents since Eisenhower seem to share an abiding temptation—they can’t let peace alone. They wish to look bold; defiance makes them pugnacious; and the military leaders promise quick victories with little pain.

We may imagine Eisenhower’s response, if he had been sitting in the room when Kennedy’s advisers told him they planned to overthrow Fidel Castro’s government by invading Cuba with a thousand men, or when they told him later to send a few thousand American soldiers to stave off defeat in Vietnam—but not too many, and as “advisers” only. Would Eisenhower have told Lyndon Johnson, oh yes, certainly, send hundreds of thousands of soldiers to do what Kennedy’s few could not? Would he have encouraged Johnson to help the Air Force pick bombing targets in North Vietnam? Would he have advised George W. Bush that seizure of Kabul and dispersion of the Taliban into the mountains were victory enough in Afghanistan? Would he have backed the urging of Cheney and Rumsfeld to send an army to invade Iraq, but not too big an army? What would Eisenhower say now about Iran?

The successors of Robert Taft share the dead senator’s views on cutting federal spending and celebrating the Christian religion, as well as his sullen dislike of such measures as Social Security, but (save Ron Paul) they are full of appetite for threatening Iran with America’s superb military. Mitt Romney was briefly in his youth a member of the Boy Scouts, but his time in uniform ended there. He avoided the Vietnam War through student deferments and thirty months as a Mormon missionary in France. But Romney supports tough action to back up tough talk on Iran, and once suggested that continued Iranian defiance on nuclear matters would merit a sharp rap “in the nature of blockade or a bombardment or surgical strikes of one kind or another.”

Hearing this, Eisenhower might have asked himself: Where do you begin?

-

*

Published this month by Knopf. ↩