Estate of Daniel M. Stein

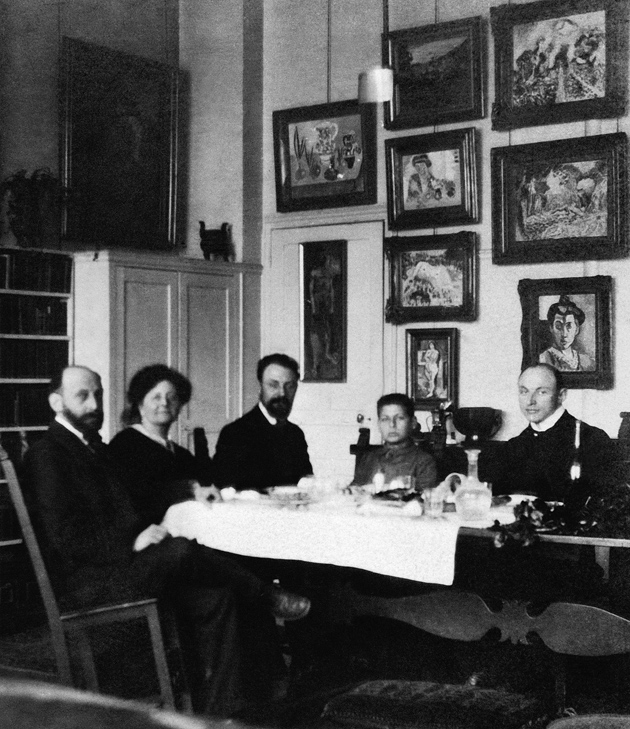

Henri Matisse (center) and Hans Purrmann (right) dining with Michael, Sarah, and Allan Stein at their apartment at 58 rue Madame, Paris, circa 1908. The paintings in the background, all by Matisse, are The Young Sailor I (far left); Pink Onions and Male Nude (left column); Fruit Trees in Blossom, Woman in a Kimono, Nude Reclining Woman, and Nude before a Screen (center column); Madame Matisse in the Olive Grove, a sketch for Le Bonheur de Vivre, and Madame Matisse (The Green Line) (right column).

Gertrude Stein endures. More than a hundred books about her have been written during the past decade or so and lately she made an appearance in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. She remains a figure of fascination for scholars of queer studies, a saint in the broader gay community, exalted as a pioneer of poetics and sexual liberation, and as the librettist of wry, cryptic texts set to Virgil Thomson’s crazy-quilt music in Four Saints in Three Acts and The Mother of Us All, both recently revived to warm reviews.

That said, even today few people manage to get through her books and poems, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas aside. Unread as always, Stein’s novels and poems nonetheless appear regularly in fresh critical editions. The latest printing of Ida from Yale University Press includes Stein’s “How Writing Is Written,” from her mid-1930s barnstorming tour of America, when she reached her triumphant peak of celebrity and made the cover of Time, and also Thornton Wilder’s “Gertrude Stein Makes Sense,” his posthumous tribute to his friend, from 1947, still perhaps the most lucid, down-to-earth aid for the head-scratching undergraduate.

And now comes “The Steins Collect” to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, after ballyhooed stops in San Francisco, where Gertrude’s family first earned its modest fortune, and Paris, where the Steins made their marks as patrons and salonists. A glamorous, occasionally revelatory affair, sprawled across close to a dozen big rooms in the museum, the exhibition, as Rebecca Rabinow, the Met’s curator, has arranged it, lavishes attention on Gertrude’s remarkable brothers, Leo and Michael, and her equally remarkable sister-in-law, Sarah. Michael and Sarah, husband and wife, who created a salon of their own on the rue de Fleurus, became Matisse’s greatest devotees, collecting and inspiring groundbreaking work and sponsoring his short-lived art academy. Classroom nudes by occasionally gifted, now widely forgotten protégés like Hans Purrmann, along with a self-portrait imitating Matisse, by Leo, occupy one gallery of the show. The hamfistedness of Leo’s picture speaks volumes.

He’s the tragic hero of the Met show, the brains behind the family’s original impulse to collect new art, a classic case of the self-taught aesthete, and one of those touching, impossible, insecure, blustery, half-cooked geniuses, vainly grappling with the mysteries and injustices of life, whose intelligence exceeded his talents and who labored for decades over a unified aesthetic theory that would bind the old and new art he loved so deeply. “Now we shall all go to Leo Stein,” Edward Steichen instructed Alfred Stieglitz in 1909. “His place is the real center.” And so Stieglitz went, to hear Leo hold forth on art. “He described Whistler as decidedly second-rate and Matisse, whom he had championed a few years before, also as second class—a better sculptor than painter,” recalled Stieglitz, who, impressed despite the misjudgment, then asked Leo to write for Camera Work.

“But Mr. Stieglitz,” Leo replied, “you see I am trying to evolve a philosophy of art, and I have not entirely succeeded in closing the circle.” He finally published Appreciation: Painting, Poetry, and Prose, a rambling, episodically enlightened meditation, not quite the magnum opus he had imagined, in 1947, just before he died. “Aesthetics had to be brought into relation with all other things in a way that made me feel that living was not altogether silly,” Leo would reflect. He had made some questionable decisions along the way. At one point he sold some of his Matisses and bought more Renoirs, which ended up in the Barnes Collection. Hostage to his own mercurial tastes and inconstant faith, art remained for him the ultimate consolation, and nemesis.

And of course to his everlasting horror it was Gertrude, whose writing he considered a sham, who meanwhile stole the limelight. “Le Stein,” as she was called—“The Presence,” as pilgrims to 27 rue de Fleurus also referred to her, not altogether admiringly—more than half a century after her death.

But these days, fame carries its costs. Among the recent publications about Gertrude, Unlikely Collaboration by Barbara Will, an English professor at Dartmouth who has written extensively about Stein’s writings, is the latest to dissect her long-known but too often overlooked affiliation with Bernard Fäy, the Vichy collaborator and Nazi agent. Will’s work, a fine-grained, unflinching, and nuanced history, details a relationship of mutual admiration, bound from the start by a reverence for Stein’s linguistic adventures. Others have looked into this. Janet Malcolm had much to say about Stein’s relations with Fäy during the Vichy period in her New Yorker essays of June 2, 2003, and November 13, 2006, which became her excellent book Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice. The friendship contributed to Stein’s Vichyite leanings and was helped, considering Fäy’s anti-Semitism, by what Will calls the “fluidity” of Stein’s Jewish affiliations. Assimilation buttressed her modernist bona fides, or so Stein believed. She came to see Christianity as the salvation of France. Jewishness became for her “a form of transgressive identification,” as Will puts it, a view acknowledged in private “in intimate moments with Toklas.” She sounds from this account like a classic self-hating Jew, whose ticket to acceptance was a perch in high culture.

Advertisement

In another of Leo’s changing perceptions of modern trends, he turned against Picasso after the artist began the experiments that led to Cubism. Gertrude defended Picasso, continued to see him, collected his works, and sat for her famous portrait by him, which required some one hundred sessions. She recognized him as a star. But the Met exhibition also makes abundantly clear that it was Leo, not Gertrude, who had the eye. The show ends with a big room of works Gertrude acquired on her own, after Leo abandoned her to her ego and to Alice. Notwithstanding that Matisse, Picasso, Renoir, and other artists they had championed became too expensive for her to buy, it’s revealing that Gertrude couldn’t do much better than Francis Rose and Francisco Riba-Rovira, both of whom painted her portrait.

“Hitler should have received the Nobel Peace Prize,” she meanwhile told The New York Times Magazine in 1934, and, alas, she apparently meant it. “He is removing all elements of contest and of struggle from Germany,” she explained. “By driving out the Jews and the democratic and Left elements, he is driving out everything that conduces to activity. That means peace.” It occurred to me, in those early rooms at the Met, looking at the genuinely radical pictures that Leo and Gertrude bought around 1906, when their home was just becoming a crucible for progressive art, that this was the same moment, as Will notes in her book, when Gertrude developed what Alice Toklas later recalled as a “mad enthusiasm” for the Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger.

Weininger, a Jewish convert to Protestantism who committed suicide (“the only decent Jew,” said Hitler’s mentor, Dietrich Eckart), wrote Sex and Character, a racist taxonomy of humanity. It had an influence over Stein’s groundbreaking novel, The Making of Americans. For Weininger, humanity broke down into categories like the Woman/Jew and Man/Genius. Weininger’s concept of genius stirred Stein’s crucial “discovery” that she was herself a genius, a type that transcends all types. A typical turn of Steinian illogic then led her to endorse dictators like Pétain. Stein translated dozens of Pétain’s speeches, hoping futilely to interest The Atlantic Monthly, and horrifying Bennet Cerf, who read her introduction to them. The speeches included those outlining Vichy’s barring of Jews like herself and other “foreign elements” from French public life.

Why she did so has long troubled her devotees. Through the intervention of local Vichy officials, she and Toklas avoided persecution in their small town in the French countryside where they survived the war. But her endorsement of Pétain clearly went beyond expedience or gratitude. Touring Germany with GIs, Stein published a revealingly blithe article in Life magazine in early August 1945 about visiting Berchtesgaden and Cologne. She made light of the war and the liberation, as if anxious to be seen to be moving on, changing the subject, reminding American readers of the quirky character who had written the best-selling Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

“We want our good writers to have good politics,” as Will laments, especially “an unquestionably progressive writer” like Stein, whose language, with its calculated instability and repetitions, its displaced nouns and verbs and small, monotonous, but subtle use of vocabulary, suggests an open-endedness that seems the opposite of reactionary. Its resistance to order, and ordering, is by definition antiauthoritarian. But then, modernism included not just Picasso and Brecht but also Pound, Eliot, Céline, Marinetti, Paul de Man, Heidegger, Philip Johnson, Yeats: the list goes on.

Advertisement

What might be called the inherent narcissism of modernist abstraction, with its inward-turning focus on its own formal means and devices, its willful divorce from the sort of close social observation and proletarian politics that caused writers like Dreiser, Zola, and Sinclair Lewis to be tarred as anti-modernists, is not incompatible with the clean-sweep radicalism promised by fascism. Nor is it inconsistent with the notion of a centralized, supreme author, or authority.

Stein was nothing if not a monumental narcissist. As she informed the boys at Choate to whom she delivered that lecture in the 1930s:

The novel which tells about what happens is of no interest to anybody…. For the last thirty years events are of no importance. They make a great many people unhappy, they may cause convulsions in history, but from the standpoint of excitement, the kind of excitement the Nineteenth Century got out of events doesn’t exist.

Instead, her goal as a novelist, she explained, had always been to listen to how people tell stories.

All my early work was a careful listening to all the people telling their story…. Really listen to the way you talk and every time you change it a little bit. That change, to me, was a very important thing to find out.

This is one of those oracular observations to which Stein was given, as she was to unfathomable, calculated nonsense. Wilder picked up on the storytelling angle in his encomium:

In the previous centuries writers had managed pretty well by assembling a number of adjectives and adjectival clauses side by side; the reader “obeyed” by furnishing images and concepts in his mind and the resultant “thing” in the reader’s mind corresponded fairly well with that in the writer’s. Miss Stein felt that that process did not work any more. Her painter friends were showing clearly that the corresponding method of “description” had broken down in painting, and she was sure that it had broken down in writing….

Miss Stein’s writing is the record of her thoughts, from the beginning, as she “closes in” on them. It is being written before our eyes; she does not, as other writers do, suppress and erase the hesitations, the recapitulations, the connectives, in order to give you the completed fine result of her meditations. She gives us the process.

One recognizes this trope in the Met show: the description of Stein’s creative process echoes the standard line on modernist painters like Cézanne. “There can scarcely be such a thing as a completed Cézanne,” Leo wrote in 1905. Cézanne’s method, he elaborated, involved “the unceasing effort to force [form] to reveal its absolute self-existing quality.”

The pleasures of the current exhibition derive not just from the intelligence and intimacy of the works the Steins collected, which they bought cleverly, with limited resources, but also from the conversations taking place, sotto voce, among the pictures. Artists, it’s obvious, stopped into the rue de Fleurus to check out what competitors were up to, then returned home and tried to do one better. The Steins’ salons played this central role. Rabinow organizes the display to suggest a call and response, showing how radical Matisse’s Woman with a Hat must have looked amid tamer pictures from the time by Bonnard, Manguin, and Picasso, which prompted Picasso and others to react; Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse is linked with Matisse’s Boy with Butterfly Net, the latter a twist on the former.

And hanging Matisse’s View of Collioure beside Picasso’s La Rue-des-Bois suggests that Picasso saw the Matisse at the Steins, brooded about it, recalled it on his summer trip into the countryside, and produced his own interpretation of it. Rabinow also makes a good case that it was not Picasso’s La Coiffure from 1906, as commonly presumed, that influenced Matisse’s picture of the same title, but Manguin’s from 1905, which Matisse would have seen at Michael and Sarah’s place. The Steins, in other words, did more than amass art. They created an incubator for it.

That so many landmarks of the Paris avant-garde of the 1900s and 1910s passed through their hands (Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre, Blue Nude, Music, Picasso’s studies for the Cubist Nude with Drapery) will, one suspects, be stimulating for droves of contemporary art collectors who keep the market humming today. The show is in the end really a paean to better times, an object lesson for our market-driven culture. The Steins weren’t unlike masses of art lovers and social climbers now who seek a place in society and history and a nest egg. But what ultimately compelled them to collect was neither money nor status.

They belonged to that golden era of rich American missionaries spreading the gospel of European modernism, amazed by the miracles of new art, true believers for whom new art meant progress and a bright shining future. Important to the show is a reproduction of a Degas pastel of a nude. It’s a collotype, or facsimile, cut out from a book, Degas: Vingt Dessins. Like a starving artist or college student, Leo occasionally cropped pictures he admired out of books and framed them on his walls, hanging this one, as can be discerned from an old photograph of his atelier, next to his prized Cézanne painting of bathers.

The juxtaposition of copy and original clearly didn’t bother him. What mattered was the art. Reproductions were convenient and cheap, so framing the Degas was partly about saving money. But mostly it was about love.

This Issue

April 26, 2012

In the Supreme Shrine

In the Heartland