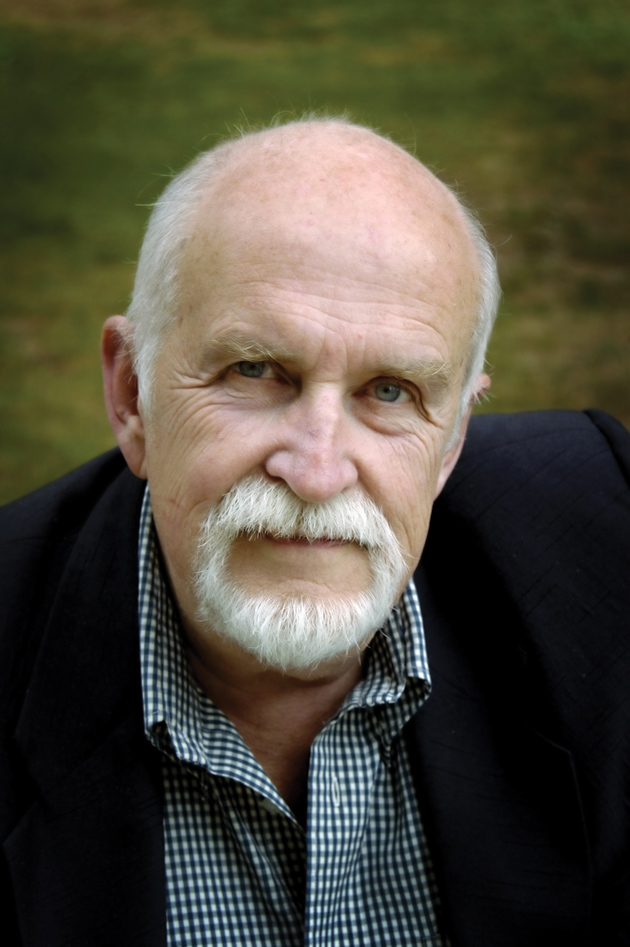

The Meagre Tarmac is the latest work of fiction by veteran story writer, novelist, and essayist Clark Blaise. Blaise has been publishing stories since the early 1970s, beginning with A North American Education (1973), which was followed by nine other collections, several of them having place names—Southern Stories (2000), Pittsburgh Stories (2001), Montreal Stories (2003). The Meagre Tarmac is a place name too, though it might not seem so at first. It alludes to the landing strips at airports—those long, thin layers of asphalt that cannot be inhabited, but nonetheless are where a number of Blaise’s characters in this book secretly feel they live, or indeed resemble: embodiments of promise, dedicated to fast motion and uprooting, stretched between here and there, prone to shimmering mirages.

The title of Blaise’s third collection, Resident Alien (1986), is also pertinent, for it describes how Blaise himself has felt all his life. Both of his parents were Canadian. His mother was a Protestant from Winnipeg, upstanding and tight-lipped and a great reader. His father was a handsome and charming bon vivant from Quebec—a classic traveling salesman, complete with the dubious philandering and imbibing habits such salesmen display in the jokes made about them.

The unlikely conjunction of this badly suited pair produced Blaise himself. He was born in 1940, in Fargo, North Dakota—a suitable portmanteau birthplace name for someone who would spend so much of his life covering long distances. He grew up partly in the southern United States, where he sometimes felt at home and sometimes did not. Then he was shuffled here and there by his parents, ever on the run from the financial and personal debris created by his optimistic though feckless dad. These embarrassing but fascinating situations were later recreated by Blaise in various stories, and in his memoir, I Had a Father (1992).

It would be almost impossible for such an upbringing to result in a person with a firm sense of a place-linked identity and an aversion to the packing and unpacking of suitcases. Much of Blaise’s work has circled around questions that were a little ahead of their time when he first began investigating them, but now seem highly contemporary: Who am I? Where am I? Where do I belong? Does nationality count for anything? Am I a part of all that I have met? What airport is this anyway? A couple of other Blaise titles act as compass needles here: The Border as Fiction (1990) and If I Were Me (1997).

During his frazzled childhood Blaise attended approximately twenty-five schools, which would certainly lead to quick-wittedness and a finely honed ability to spot and classify accents and social quirks and differences. His adolescence was spent in Pittsburgh, where he was bedeviled not only by high intelligence, but by what was at first called “double jointedness” but is now known as myotonic muscular dystrophy—an altogether more serious business that can have lethal consequences. (His party trick as a child was a demonstration of literary bendiness: he would shape his rubbery fingers into the letters of the alphabet, to the applause of some of the watching adults and no doubt to the consternation of others.)

This genetic disorder provides a limited answer to at least one of the Blaisean questions, for—as Blaise later discovered through medical research and by tracing his own family tree—it is highly prevalent among a limited group of interrelated Quebecois, having been introduced to the Lac-St-Jean region in the eighteenth century. You want to “belong”? Fate seems to have asked him. Try belonging to this.

Somehow young Blaise untangled himself from the family drama sufficiently to make his way to Denison College, and then to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at a time—the early 1960s—when it was almost the only such scribe-centered game in town. There he met and married Bharati Mukherjee, who was similarly in flight, in her case from the expectations an Indian girl of her class was expected to fulfill. Clark Blaise was so in awe of her aristocratic Anglo-Indian manner that he thought of her not only as “Miss Mukherjee,” but as “Miss Miss Mukherjee.”

Then, as part of Blaise’s ongoing attempt to connect with his admired but rascally and elusive father, they moved to Montreal, where Mukherjee—not yet the published author who would herald the arrival of a generation of ocean-crossing Indian writers such as Pankaj Mishra and Jhumpa Lahiri, but already armed with a Ph.D.—taught at McGill. Blaise—less well equipped with degrees—was at Sir George Williams (now part of Concordia), a downtown edifice with a block-like shape. At this period of his life Blaise was taking a shot at being Canadian: his parents were, after all, and he’d had close encounters with both kinds of relatives, the restrained English-speaking Manitobans and the much more unbuttoned Quebecois. (Mukherjee was not quite so eager: she identified Canada with the British Raj, that state of unfreedom for Indians, and wept when crossing the border.)

Advertisement

It was a time of considerable ferment for writers in Canada. Since there was a shortage of publishing houses in the country, some writers were inventing their own. Many were involved with literary magazines, and with various forms of cultural nationalism and postcolonial self-assertion, generated by the feelings of invisibility and inferiority that were widespread also in Australia and New Zealand, among other countries. It was difficult to get a novel published in Canada—where was the sufficient readership, the larger publishers wondered? (It was in this decade that a New York publisher said to me, “Canada is death down here.”)

But there were a lot of visible poets—poetry was short, and you could crank out your own chapbooks in the cellar. And there was a market of sorts for stories, on the CBC radio program Anthology, in other anthologies such as the ones put together for Oxford University Press by Robert Weaver, in the literary journals, and even in the odd commercial magazine. A disproportionate number of Canadian writers—Alice Munro and Mavis Gallant foremost among them—have become well known primarily through short stories, and this is the fictional form most often chosen by Clark Blaise. In the early 1970s, when publishing in Canada was expanding at a rapid rate and public readings were exploding, Blaise joined with four other writers to form the Montreal Story Tellers Fiction Performance Group. But he was born under a wandering star, and it wasn’t long before he set up shop in Toronto, only to head south again to lead Iowa’s International Writing Program.

It was during the earlier period—Montreal in the 1960s—that I myself met Clark Blaise, for I too was a rookie teacher at Sir George. At Sir George you taught the same courses at night that you taught in the daytime, but to adult students, much more eager to learn and also to dispute. I was twenty-seven, Clark was six months my junior, and during the winter of 1967–1968 we hung out together in the cafeteria in the interludes between our daily and nightly stints. Even at that tender age, Clark Blaise already knew a lot. He was like that old song “I’ve Been Everywhere,” because he had been everywhere, or almost. In his case the song could also have been called “I’ve Read Everything.”

Luckily he was amusing, which can cover up for a certain amount of erudition. When prodded, he would give oral samples of the several languages he already spoke or was learning (including Russian, Hindi, German, and both kinds of French), while adjusting his face and body language appropriately. He would have made a good spy, or contortionist. Imitations can verge on parodies, and some of his did. It’s a risk run by those aiming for national or gender portraits, but happily it’s something Blaise manages to duck in The Meagre Tarmac.

Anyface is also No-face, and “who am I really” is a recurring Blaiseian question, which may be the most obvious link between Blaise himself and his Meagre Tarmac characters. More than ever, Blaise is probing his core question: Is it better to be Caliban, of the earth, earthy, with deeply felt territorial passions, or Ariel, of the air and rootless? Can one be both?

The Meagre Tarmac is a collection of eleven smart, peculiar stories—I use “peculiar” in the sense of particular and distinguishing—that are linked through time, space, and the characters who weave themselves into one another’s plots. Most surprisingly for those readers who have followed Blaise’s writing to date, The Meagre Tarmac avoids any obvious marks of autobiography.

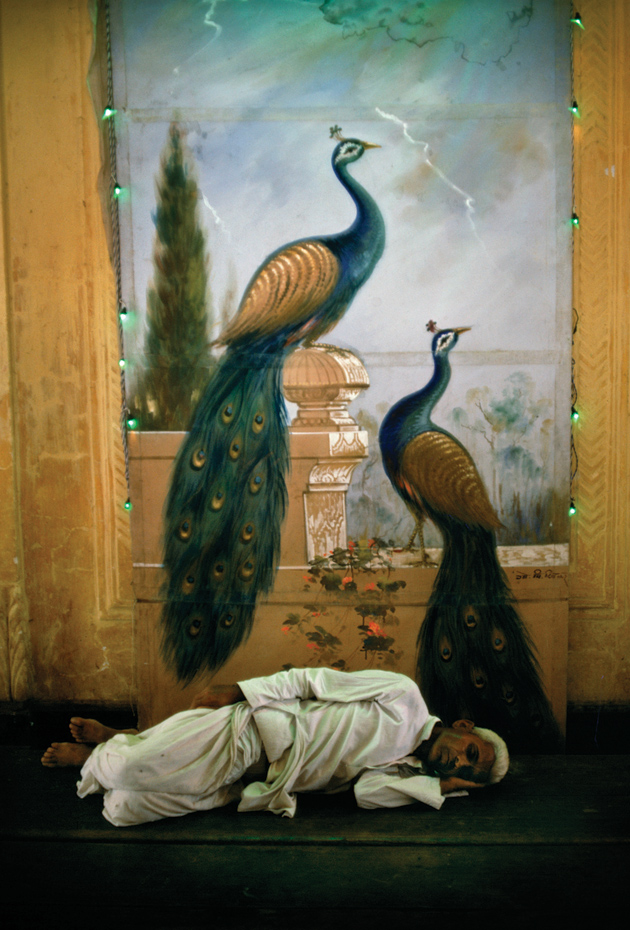

The stories are all told by people who—like Blaise’s wife, through whom he has learned much about that other culture—are Indian in origin, in one way or another. All are also puddle-jumpers: they’ve immigrated, to America, to Canada, to Britain; they’ve done well, either in Silicon Valley or in Hollywood or New York; they’ve immigrated back again; and in one case—that of two American adolescents whose father intends to move the family to India—they are about to be immigrated, against their wills.

A couple of decades ago Blaise would doubtless have been accused of “voice appropriation” on half a dozen counts, for not only are the characters all not-Blaise, they are not remotely Blaise. They’re various ages, from fourteen to eighty; they’re various genders and inclinations—straight male and female, gay male, bisexual female; they’re various religions—Hindu, Parsi, Goan Christian (more or less). Such multiple impersonations would seem both overly ambitious and dauntingly hard to pull off, but Blaise has always had an ear for accent and a grasp of social attitude, and these talents do not fail him here. Happily for him, “voice appropriation” has been downgraded on the list of knee-jerk literary sneers, and whether you’ve appropriated a voice is now of much less interest than whether you’ve done it well.

Advertisement

The Meagre Tarmac’s first three stories concern the Waldekar family—Vivek the father, Krithika the mother, Jay the teenaged son, Pramila the thirteen-year-old daughter. Vivek narrates the first story, “The Sociology of Love.” He’s middle-aged, he has “succeeded” in America—though not as much as some of his early friends—but his life is turning to ashes. This is made more apparent to him by the appearance at his front door of a very tall blond Russian beauty in a skimpy T-shirt that says “All This and Brains, Too.” She claims to be conducting a sociology survey of Indian success stories like himself, but really she wants to connect with Indians for consolation, since a classmate of Vivek’s son has just dumped her in order to marry the family’s wife-of-choice back in Mumbai. “Please, take water,” is about all Vivek can offer in the face of her heartbroken sniffling, as he peers at her large breasts with their butterfly tattoo.

Vivek’s own marriage was similarly arranged, and—disrupted by America and its sexual temptations, to which he succumbed while his wife, Krithika, was still back in India—it has not turned out well. Krithika is cold and resentful, fixated on her kids and their progress. As is Vivek; for, as he says, “What else is there on this earth, I want to ask, than safeguarding the success of one’s children?”

The next narrator, Pramila, is one of those children, but she is a girl child, and Vivek computes success differently for her, because “pride is not good in a girl.” Pramila has not been squashed flat by her father, not yet: she delivers herself of a spirited and engaging monologue in a perfect story called “In Her Prime.” Pramila is precociously bright, a mathematical genius; she is due to go to Stanford the next year. She is also, as her mother puts it, “a champion figure skater.” But unbeknownst to the Waldekars senior, Pramila’s Russian skating coach is in the habit of sleeping with his young pupils, one after another, and right now it is Pramila’s turn, though—as she has already been molested by her older brother—this is not her first sexual encounter; nor is she resentful, because at least Borya notices her as a person. Her younger fellow pupil, Tiffy Hu, guesses, and asks her what sex is like. What Pramila thinks is, “It’s like a puppy of some rough, large breed that just keeps jumping up and licking your face.” What she says is, “It makes you sleepy.”

Pramila has already learned to keep a thick wall between what she thinks and what she says, for whatever freedom she enjoys depends on secrecy. She knows a lot more about her own family than anyone else in it knows, because she’s a watcher and a listener. “Sometimes it’s good to be a quiet, studious, Indian daughter,” she thinks. “I’m just furniture.” When her father makes it known that he’s moving the family back to India to “protect” her, though in reality he’s fleeing the possible reappearance of his lover of long ago, Pramila finally manages an outburst. “If you try to make me go back to India and if you stop me from going to Stanford and you try to arrange a marriage with some dusty little file clerk, I’ll kill myself,” she tells Vivek.

But evidently he doesn’t take this in, because in the next story Vivek is back in India, possibly arranging for the move, although his wife doesn’t think he will be able to manage it so easily, now that India is booming and a man returning from America no longer has the instant prestige or indeed the high rate of exchange he once would have enjoyed. While Vivek is away, Krithika, who has long felt like “furniture” herself, has a tiny fling of her own with a Muslim grocer, thus crossing multiple borders—race, class, religion—and revealing a part of herself no one in the family has suspected. She manages to elude even the watchful Pramila, who through the eyes of Krithika is less a precocious genius than a sulky adolescent girl. We do not find out what happens to Pramila, although we would very much like to: she’s a wonderful creation, caught in a perfect story.

No one else in the book is as young as Pramila, though all of them look back on their earlier selves—the selves they were before their encounters with the West rewarded them materially and eroded them spiritually, and in some cases embittered them. Wonder, nostalgia, and regret are in ample supply, especially among the men. For America they feel some gratitude—they have, after all, “succeeded”—but also some contempt, because Americans don’t understand complexity and have, in their view, such shallow interests and such low standards of public and sexual behavior. Mr. Dasgupta, in “Isfahan,” feels outrage when casual American racial profiling hits him at JFK airport and he’s roughed up as a possible terrorist. It’s the gap between the brutality of the treatment and who he knows he is—“Forbes 500! Hell, Forbes 35!”—that particularly galls him. Many of the characters share the divided emotions of the girl visiting the Dasgupta household: “One minute she’s attacking everything about India, it’s all corrupt, all rotten, and everything about America is great and good and even glorious, and the next, she’s weepy with nostalgia for just about everything in India that even I find appalling,” says Dasgupta, who nevertheless has decided to return to the motherland.

But the further a character departs from the Indian male ideal, the more likely he or she is to have found a viable niche in the Western world. Alok, for instance, is extremely handsome and also gay, and has become an actor, even though “the one profession never mentioned and never permitted for an Indian son is anything remotely approaching the arts.” Connie da Cunha, from the once-Portuguese ex-colony of Goa, has become a much-respected lesbian editor in New York, though she is then brusquely ejected when her publishing house is taken over by bean-counters, much as Goa itself was taken over by India. Back in Goa, struggling to write—at last—her own book while wondering if it’s even worth doing, she reflects: “The columns she’d filled in—editor, cosmopolitan—…are the common baggage of the Third World…. The lives of people like her seemed the endless middle of an unticketed journey.”

It is Connie, too, who reflects, “It is a tight, mysterious fraternity, those who grew up with unconsummated love or complicated hate for their colonial masters.” In the midst of her story, the reader has some difficulty remembering who in fact wrote it—not a middle-aged gay female, London party girl, and erstwhile New Yorker, but one of those elderly white straight males such a person would once have made offhand, derogatory jokes about. Why, in The Meagre Tarmac, did Blaise decide to stray so far from his usual terrain?

But again, why not? It isn’t as if he hasn’t been on both the giving and the receiving end of such complex trans-cultural exchanges. Canada/America, South/North, Quebec/English Canada, India/North America—he’s familiar with the osmosis, and the resentments. Perhaps India/North America is yet another embodiment of the push-pull drama between mother and father he’s enacted so often before, with the bright, observant child—himself or Pramila—stretched between them.

Or perhaps the elegant stories in The Meagre Tarmac constitute a warning of sorts. Once upon a time the “colonial masters” didn’t much care what those they were mastering thought of them, but now the situation is different. As so many Tarmac characters discover, India is different now: it’s a lot richer, it has power on the world stage. The old tables are turning. Maybe the attitudes explored by Blaise will soon be subject to anxious or calculating scrutiny. Why did Vivek Waldekar never feel at home in America? What did he fail to learn, and what has America failed to learn about him? Why doesn’t he want his children to marry Americans, anyway? The Meagre Tarmac—deft, intricate, wickedly observant—may help us find out.