Here is a book you can tell by its cover. In this deeply critical biography, Lewis Sorley argues that William Childs Westmoreland (1914–2005) was responsible for the American loss of South Vietnam, where from 1964 to 1968 he was the military commander. The immaculately turned-out, chisel-jawed general had been for the most part admired until he was elevated to command in Saigon. But some of those who served with and under him during his four years in Vietnam—ambassadors, fellow generals, even a sergeant major of the Army—considered that after Westmoreland took charge in Saigon this vain, incurious, and sometimes dishonest man proved unfit for supreme command.

For years, most books on the Vietnam War reviewed in these pages held that Washington’s policymakers underestimated or ignored Vietnamese nationalism and other realities. Some of those books concentrated on the early centuries of Vietnamese struggles against imperial China, and their later defeat of their French colonial masters. Nowadays we learn that American commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan, having studied the Vietnam War and its history at the military academies and in command schools, determined not to repeat the mistakes in Vietnam and, more significantly, read studies that showed how the war could have been won. Andrew Krepinevich published an early exposition of this view, The Army and Vietnam, in 1986. There were others. In his 2006 book, Triumph Forsaken, for example, and in at least one subsequent article, Mark Moyar emphasized that beginning with White House collusion in the murder of President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963, US policies crippled a possibly winnable war.

In 1999, Lewis Sorley, a West Point graduate and Vietnam veteran who served in the Pentagon in the office of the Army Chief of Staff when Westmoreland held that post, and in the CIA, published A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam. In it he maintained that General Creighton Abrams, Westmoreland’s successor in Vietnam, all but defeated the Vietnamese enemy. That near victory, Sorley claimed, was undermined by politicians in Washington; they were rattled by a nervous public, a fickle press, pictures of body bags, and, after the 1968 Tet Offensive, by television images of dead Vietcong inside what misleadingly appeared to be the American embassy.

Surrounded by dead Vietcong, Westmoreland was not boasting when, after the Tet Offensive, he proclaimed in the embassy compound, “The enemy’s well-laid plans went afoul” and declared, truthfully, that no Vietcong had entered the building. But he was not believed. Television pictures of dead Americans and guerrillas in Saigon convinced many at home that years of fighting and heavy American casualties were a costly disaster.

In his new book Sorley makes plain his scorn for Westmoreland’s military views and some of his personal characteristics. His strategies—Search and Destroy, Attrition, and Body Count—relied on ratios intended to show that if enough Vietcong and North Vietnamese soldiers were killed for every dead American, this would eventually force the enemy to fade away. This, Sorley contends, underestimated two factors. A senator from Westmoreland’s home state of South Carolina warned the general, who had just told him, “We’re killing these people at a ratio of 10 to 1,” that “Westy, the American people don’t care about the ten. They care about the one.”

As for Hanoi and its southern allies, they were willing to expend millions of lives, including civilians north and south, a long view that Vietnamese novels—some of which I have reviewed in these pages*—showed led many North Vietnamese soldiers to despair but not surrender. Their huge losses during Tet and the absence of a “general uprising,” which caused them to scale back their efforts for months, surprised Hanoi and the Vietcong but did not cause them to collapse. Nonetheless, Westmoreland continued to insist:

Now our strategy…was not to defeat the North Vietnamese army. It was to put pressure on the enemy which would transmit a message to the leadership in Hanoi—that they could not win, and it would be to their advantage either to tacitly accept a divided Vietnam, or to engage in negotiations.

Sorley quotes a Pentagon official: “Westy believes the war begins and ends with killing VC.” Krepinevich described this as “Whack-a-Mole.”

Westmoreland also opposed giving more effective weapons like the M-16 rifle to South Vietnamese soldiers who were fighting an enemy armed with AK-47s. According to some of his subordinates, Westmoreland insisted that the better rifles would end up in the hands of the enemy. General Fred Weyand said after leaving Vietnam in 1968, “The long delay in furnishing ARVN [Army of South Vietnam] modern weapons and equipment, at least on a par with that furnished the enemy by Russia and China, has been a major contributing factor to ARVN ineffectiveness.” But General William DePuy, who also had served in Vietnam, admitted later:

Advertisement

I guess my biggest surprise…and this was a surprise in which I have lots of company, was that the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong would continue the war despite the punishment they were taking…. I guess I should have studied human nature and the history of Vietnam and of revolutions and should have known it, but I didn’t. I really thought that the kind of pressure they were under would cause them to perhaps knock off the war for a while, at a minimum, or even give up and go back north.

That was an enlightening admission: it did not blame Westmoreland, although his views had been the same as DePuy’s. As for Vietnamese history, Sorley and others disparaged Westmoreland for rarely reading anything. He kept Bernard Fall’s books on Vietnam and Mao’s treatise on guerrilla warfare at his bedside—but these, Sorley says, were “mostly for atmospherics,” and he doubts they were read. And most of Westmoreland’s military colleagues and the policymakers in Washington were similarly illiterate about what was going on in Vietnam.

Sorley notes that senior officials in Washington like McGeorge Bundy and Robert McNamara

had begun to perceive the problem with Westmoreland’s approach…. What is baffling is that these senior civilian officials nevertheless allowed Westmoreland to doggedly pursue his flawed approach for year after bloody year.

This is not baffling. The late James C. Thomson, who served in the State Department and White House from 1961 to 1966, explained the Vietnam mistake:

A recurrent and increasingly important factor in the decision-making process was the banishment of real expertise. Here the underlying cause was the “closed politics” of policy-making as issues become hot: the more sensitive the issue, and the higher it rises in the bureaucracy, the more completely the experts are excluded while the harassed senior generalists take over (that is, the Secretaries, Undersecretaries, and Presidential Assistants)…. Even among the “architects” of our Vietnam commitment, there has been persistent confusion as to what type of war we were fighting and, as a direct consequence, confusion as to how to end that war.

Fundamentally, Thomson wrote:

A first and central ingredient in these years of Vietnam decisions does involve history. The ingredient was the legacy of the 1950s—by which I mean the so-called loss of China, the Korean War, and the Far East policy of Secretary of State Dulles.

Important facts about the enemy on the ground were easily available at the time, even if the policymakers and generals knew nothing of Vietnamese history. From the early Sixties, and very near Saigon in My Tho province, the Rand Corporation was conducting interviews with Vietnamese peasants and captured enemy soldiers. David W.P. Elliott, a participant in the Rand enterprise, and Mai Elliott have analyzed these interviews to great effect. David Elliott writes:

There was genuinely widespread support for the revolution in places like My Tho…. The interview accounts of this period [1961–1964] make it absolutely clear that there was a revolutionary high tide during these early years of the Vietnam War.

After his experience as a soldier and an interviewer in the field, Elliott disputes the supposition that

the peasants were a neutral force, indifferent to all sides…. It is my conviction that the data in this study will not support the concept of a neutral peasantry…. Between 1930 and 1975 the Mekong Delta underwent a sweeping set of transformations, many set in motion by the revolutionary movement. Perhaps the most significant of these was the evolution of the mental world of the peasants in the Mekong Delta from subjects to citizens.

Such data and such conclusions, the result of years of work a short drive from Saigon, were near at hand for any officer there at the time, such as Sorley, and for policymakers like Bundy and McNamara during their trips to Vietnam.

Although Sorley believes that after Westmoreland departed in 1968, Creighton Abrams’s war was a fundamentally different one, this was not so in the delta. After Tet in 1968, Elliott observed, “The US–GVN [Government of Vietnam] response pushed war to an unparalleled level of intensity.” Even Hanoi, he says, was taken aback by not only this escalation but also the extension of hostilities into Laos and Cambodia. “This had tragic consequences for the civilian population of My Tho, which suffered extremely heavy casualties during the prolonged US exit.” Elliott adds that until Tet

the much maligned General Westmoreland had earnestly attempted to minimize civilian “collateral damage” and preferred to fight in remote areas, partly out of concern for the effects on Vietnamese noncombatants.

Abrams, who replaced Westmoreland in June 1968, Elliott states, “was an aggressive tank commander from the General Patton school, and had little patience for these niceties.” Sorley admired Abrams for abandoning his doctrine of Search and Destroy, but Elliott shows that he championed “clear and hold” operations like “Speedy Express,” in which the Ninth Division “had taken off the kid gloves” during its six-month operation in the delta. This led to an enormous number of civilian casualties, concealed in the claimed “10,000 ‘VC KIA’ (killed in action).” The Ninth Division received a unit award “for humanitarian interest in the Vietnamese people,” but a senior officer, Admiral Robert Salzer,

Advertisement

concluded that one brigade commander of the 9th Infantry Division was “psychologically…unbalanced. He was a super-fanatic on body count. He would talk about nothing else during an operation…. You almost see the saliva dripping out of the corners of his mouth. An awful lot of the bodies were civilians.”

Mai Elliott observes that General Julian Ewell, commander of Speedy Express, “believed that…‘the only way to overcome VC control and terror is by brute force.’” David Elliott states that the effects of Speedy Express were worse than the My Lai massacre because they were policy.

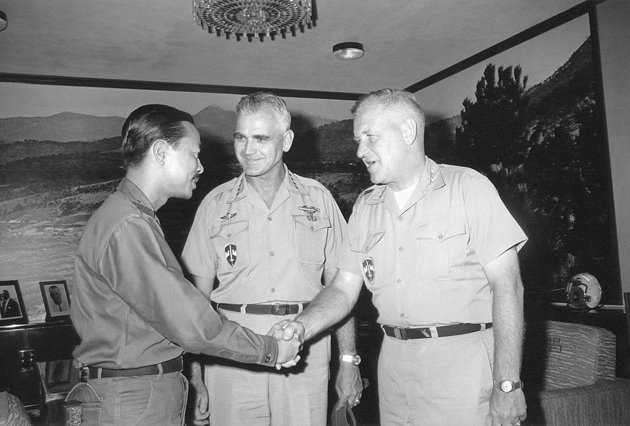

Westmoreland never lost the self-confidence first noticed when he was a cadet at West Point, which until Vietnam stirred men to respect and follow him. In 1965 I was prowling around the general’s unguarded personal plane parked at the Saigon military airport. Vietnamese in and out of uniform were everywhere, many of whom, it was known, were not fond of the Americans. I saw Westmoreland not far away and told him that it would be easy to hide a bomb on his plane. He told me not to worry about it.

Years later, when the general, now retired and on a speaking tour in London, was still insisting that if his policies had been followed victory would have been inevitable, I reminded him of that little episode. He leaned over and told me firmly, “The Vietnamese war was the first war in history lost in the pages of The New York Times.” Then he quite deliberately swept my tape recorder off the table, shattering it against the wall. The young woman who was escorting him to his appointments told me that while they stood in the rain outside the BBC waiting for the door to open, water was pouring off the roof directly onto Westmoreland, who stood under the torrent without moving or complaining.

Those who are guiding American strategies in Afghanistan will fail if they believe they have learned the lessons of Vietnam from reading Lewis Sorley’s books, which are inconsistent. His earlier work emphasized that General Abrams was near victory in Vietnam and, unlike his new book, did not blame Westmoreland for the eventual defeat, concentrating instead on a political stab in the back. Sorley quoted Samuel Berger, one of the deputy ambassadors in Saigon, reflecting on Abrams:

He died feeling we could have won that war. He felt we were on top of it in 1971, then lost our nerve.

But over a million Vietnamese, many of whose bodies were never recovered, and thousands of Americans in their body bags, did not die simply as the consequence of weak politicians in Washington or the failings of one general.

These consequences resulted from the United States going to war in pursuit of a false goal: preventing the sweep of communism through Southeast Asia. Apart from Indochina, where this was always on the cards and where, especially in Cambodia, communism took hold more quickly owning largely to American intervention, it never reached the rest of the region.

In April 1991, at a public meeting in Kyoto where he was urging the outlawing of intercontinental missiles, I asked Robert McNamara, long retired as secretary of defense, whether the deaths he had helped cause in Vietnam were worth it. At first he refused to answer, but suddenly ground out: “I was wrong. My God, I was wrong.”