For many years, specialists in universities believed that American political events could be explained by the methods of economics and political science. The recent lackluster jobs report, for example, showing just 120,000 private-sector jobs added in March, is precisely the sort of fact that these experts would find explanatory. They assumed that party politics didn’t really matter that much—that when it came, for example, to making decisions about economic policy, politicians of both parties, though they would disagree on some fundamental questions, acted rationally, listening to the views of their respective economic experts and attempting to carry out their recommendations in as much good faith as the sausage-making processes of party politics would allow.

It took them a while, but that view has begun to change. Now, the components of politics—everything from ideology to the influence of money to overbearing egos and hostile personal relations, all the matters that have for decades consumed the political press but been of less interest to the academy—are understood to drive the action. Or at least acknowledged as factors. The influential books along these lines include Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson’s Off Center of 2005, in which the writers—political scientists—described the process by which a comparatively small and radical Republican group of lawmakers and their benefactors had moved the country so far to the right. Two years later, in The Conscience of a Liberal, Paul Krugman admitted that he’d been wrong all these years in putting economic explanations before political ones. Considering inequality, for example, he wrote that he’d been coming to conclude that mere economic explanations for it no longer sufficed:

Can the political environment really be that decisive in determining economic inequality? It sounds like economic heresy, but a growing body of economic research suggests that it can.

The year after that brought publication of the political scientist Larry Bartels’s Unequal Democracy. Bartels, now at Vanderbilt, then at Princeton, was, like Krugman, concerned in the first instance with our growing (not to say rampaging) economic inequality. He didn’t want to believe that a factor as pedestrian as which party the president belonged to could really matter in determining inequality. But after studying the evidence and finding that inequality had tended to increase dramatically under Republican presidents and decrease under Democratic ones going back to Harry Truman’s day, Bartels confessed: “If this is a coincidence, it is a very powerful one.”1

I would add finally to this list the bracing new book Why Nations Fail, by the economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson,2 who survey societies from ancient times to medieval Venice to post-1688 England to today’s China, looking to pinpoint the reason why nations rise and fall. The answer, they write, is the creation of economic institutions that permit broad prosperity. But those institutions are created in the first instance by politics, so the real question for Acemoglu and Robinson is whether a nation’s political institutions permit the creation and flourishing of economic institutions that are “inclusive” of the general population. The United States, they find, has had such political institutions historically, but these days the authors are worried.

So here we are, a century and a half after Marx, living with the effects of George W. Bush, Karl Rove, and Dick Cheney—and more recently, Sarah Palin, the Tea Party movement, and a group of Republican presidential candidates willing to make assertions like Rick Perry’s lament that in Barack Obama’s America “our kids can’t openly celebrate Christmas.”3 Social scientists are flipping the old base-superstructure relation on its head and acknowledging that politicians are not rational decision-makers, and that politics drives economics, not the other way around.

An entire subspecies of the politics-economics debate is devoted to the study of campaigns. Here, to oversimplify just a bit, you have some political scientists on the one hand arguing that election results are almost wholly determined by the economic conditions at election time (the “fundamentals,” in the argot) versus those (mostly journalists) who believe that campaigns—the big decisions, the little gaffes, the controversies along the way and how they are handled—matter.

It’s natural that political scientists would look to economic factors first. They find it difficult to quantify the impact, for example, of Palin’s disastrous 2008 interview with Katie Couric, when she couldn’t name a newspaper she read or a single Supreme Court case beyond Roe v. Wade, so they tend to downplay these kinds of events. The political reporters, in contrast, obsess over them—to a point of absurdity, in the view of many political scientists—and insist that election results turn almost wholly on these much-publicized matters. The recent fuss about a Romney campaign adviser’s reference to his candidate’s views being as changeable as an Etch A Sketch is a case in point.

Advertisement

The George Washington University political scientist John Sides, who tends strongly toward the “fundamentals” view, blogs at an informative and useful site called The Monkey Cage, to which several liberal academics contribute posts. After the Romney aide made the Etch A Sketch remark on March 21, suggesting that after securing the nomination, Romney could in essence wipe the slate of his positions clean and adopt entirely new ones, a debate broke out among liberal commentators about whether it would be more effective for the Obama campaign to attack Romney along Etch A Sketch lines—as a flip-flopper—or as an agent of the top 1 percent. Sides set out to quantify this, and he found, after studying some poll results and crunching some numbers, that an attack on Romney as an Etch A Sketch flip-flopper would make political independents 31 percent more likely to support Obama, but that a strategy attacking Romney as an economic elitist would make those same independent voters—strangely ignored in much recent commentary—61 percent more likely to back the president.4

Those (I include myself here) who think of both political analysis and campaigning as more art than science tend to wonder about such analyses, although some journalists have written quite sympathetically of the argument that economic fundamentals count (for example, Matthew Yglesias and Ezra Klein, probably the two most prominent young journalists on the liberal side). A recent attention-getting development came from Nate Silver, who generated a large following during the 2008 campaign for his precise (and accurate) statistical analyses, and who now blogs at The New York Times. Challenging the fundamentalists, Silver surveyed the postwar period to see if the economic interpretation of presidential election results really held up. Going back to the 1940s through the 1960s, he found, not so much. Then, from 1972 to 1988, he conceded a relative heyday for political science. And since?

But is it true? Can political scientists “predict winners and losers with amazing accuracy long before the campaigns start”?

The answer to this question, at least since 1992, has been emphatically not. Some of their forecasts have been better than others, but their track record as a whole is very poor.

And the models that claim to be able to predict elections based solely on the fundamentals—that is, without looking to horse-race factors like polls or approval ratings—have done especially badly. Many of these models claim to explain as much as 90 percent of the variance in election outcomes without looking at a single poll. In practice, they have had almost literally no predictive power, whether looked at individually or averaged together.5

As the old E.F. Hutton ad had it, when Silver talks, people listen. Some back-and-forth has ensued, and some challenges to Silver have been published. But the argument based on economic and social fundamentals has certainly been sacked for a loss.

It is in this setting that Samuel Popkin, a professor at the University of California at San Diego and one of the best-known political scientists of his generation, has written The Candidate. I first encountered Popkin’s work in graduate school in the 1980s, noticing then in some of his writing that he seemed to enjoy politics to an unusual degree for a political scientist. He has been more engaged than most in his field, advising the campaigns of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and others.

Popkin has believed since the 1970s that politics really matters, that gaffes such as those of Palin’s campaign are more important than economic fundamentals; and he appears to revel in the view. The Candidate is his attempt “to explain the intricacies of a presidential campaign by examining the winners and the losers, the small details and the big picture, the surprising mistakes and the predictable miscues.” It’s so far from emphasizing economic and social trends that it could almost have been written by a Politico reporter.

If you’re going to read one book by Popkin, you might still want to make it 1991’s The Reasoning Voter, an update of V.O. Key’s “rational voter” thesis where he first argued persuasively that campaigns and candidates matter. In The Reasoning Voter, which was influential for Clinton aides like James Carville, Popkin coined the term “low-information rationality”—which means, roughly, gut reasoning—to describe the way most voters think. More recent works—Drew Westen’s The Political Mind and the new book The Righteous Mind by the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt—have taken this notion even further, trying to analyze the precise mechanisms by which voters very loosely use reason and facts to support conclusions they’ve already reached intuitively. But The Reasoning Voter was groundbreaking in this regard.

The Candidate repeats some of Popkin’s earlier arguments but it is valuable in at least two respects. First, he updates his ideas to cover the 2008 campaign. A lengthy chapter on that year’s Democratic primary battle is a useful case study for those who argue that “politics matters,” because the economy wasn’t really much of an issue in those early battles (this was before the 2008 crash, and the candidates didn’t really disagree on much).

Advertisement

Popkin ascribes Obama’s victory over Hillary Clinton to decision-making that was more in tune with the moment; his campaign operation, nimbler than Clinton’s; and simply his way of relating to audiences:

The rhetoric Clinton used in debates throughout 2007 was more self-centered and credit-claiming—and less inclusive and unifying—than that of Obama. Whether she was trying to act above the fray and project inevitability, or even Thatcher-like strength, she used self-centered “I-words”—I have, I am, I will—50 percent more frequently than she used “we” words. While she was asserting her preeminence, he was trying to build relations with the audience.

Would Clinton have won if she’d said “we” more than “I”? Only, in my view, if the more inclusive pronoun had been used in sentences like “We never should have gone into Iraq,” since her support for that war was her biggest problem. The difficulty with observations like Popkin’s, at least to some of his fellow political scientists, is that their impact is utterly unquantifiable. And yet, that impact is also undeniable. Little moments both positive and negative—Clinton producing a tear in New Hampshire in 2008, John Kerry ordering a Philly cheese steak with Swiss cheese in 2004—may, over the months or longer, form a portrait, often accurate, of just who this person is. (Who of Gail Collins’s readers will forget her repeated image of Romney’s Canada-bound Irish setter tied to the car roof?)

Popkin loves such ephemera, but he doesn’t build his case solely around them. Hence, the second valuable aspect of The Candidate is his insistence that what matters above all else is the team, and especially the immediate supervisor of that team, the chief of staff. He goes so far as to assert:

Weak chiefs of staff are the biggest reason campaigns flounder. A chief of staff is weak not because of her personality or character but because the candidate sets her up to be weak…the candidate never gives the chief enough authority to mediate and coordinate, let alone level with the candidate.

This seems convincing to me. In my own experience, the winning campaign was usually the one less riven by internal disputes and jealousies, and that campaign almost always had a strong person overseeing it. A touch of messianism among the staff helps—a sense that they are saving the country (or state or city) from some condition of turpitude to which the opponent’s victory would surely assign it. That tends to keep the egos of the staff in check. In 2008, the Obama people felt that sense of cause more strongly than the Clinton people or John McCain’s team, or even the acolytes of Sarah Palin.

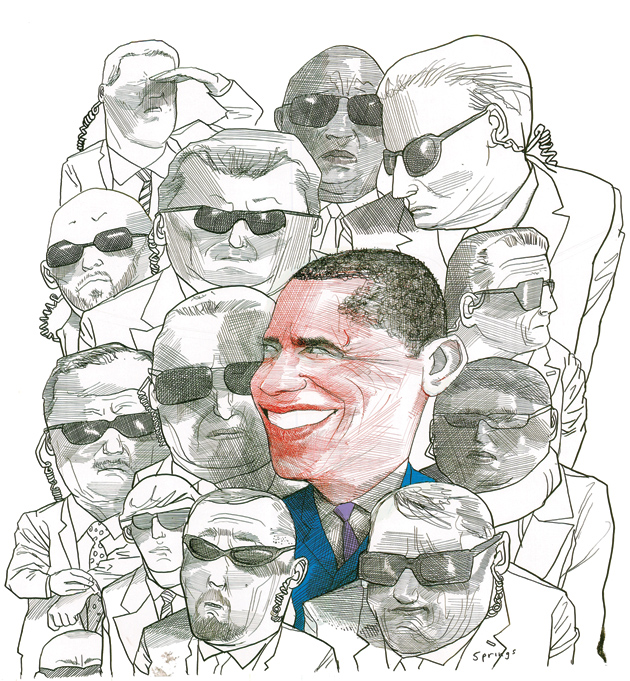

What do Popkin’s criteria tell us about this election? On the question of teams, both candidates are well set up. Obama will have a familiar group around him, essentially the same one that guided him to victory in 2008. By and large this team made excellent decisions in 2008 in running the campaign, but in governing, often not very good ones at all. We did not see a convincing and strongly publicized national program—or programs—to create jobs, for example. One of the big questions about David Axelrod, David Plouffe, and the others is whether returning to the campaign will resharpen their judgment. Axelrod in particular is probably more adept at campaigning than he was at governing.

Romney’s campaign manager is Matt Rhoades, who worked in public relations during Romney’s campaign in 2008. Just thirty-seven, Rhoades’s name rarely makes the papers, which from Popkin’s perspective is a good sign for the candidate. He hasn’t given a single on-the-record interview during this entire campaign, never appears on television, and has by most accounts no desire to convert his job into a recurring spot on Fox News. Most other top aides have been around Romney since at least 2008.

It is unsurprising, then, that Romney’s campaign has been as disciplined as it has. One hears, for example, few leaks from unnamed sources inside the campaign complaining about this or that stratagem. The Etch A Sketch error, committed on cable television by senior adviser Eric Fehrnstrom, is the one big muck-up by the campaign that I can recall, and even then it was a matter of just one sloppily chosen metaphor. The Romney campaign’s problem is not the team but the candidate, who puts his foot into his mouth almost every week. These mistakes have not done him much damage while he’s been running against a field of people who plainly are not plausible potential presidents. Things will be different when he’s facing an incumbent president who is a skilled campaigner.

So where might this election fall, on what I might call the Sides-Silver scale? Will the outcome be largely determined by the condition of the economy in October, or will events large and small, and how the campaigns react to them, decide matters? The movement we’ve seen so far in the race provides a bit of ammunition to both sides of the argument. Three or four months ago, Obama and Romney were tied in most polls. Today, Obama leads by anywhere from 4 to even 10 percent. What’s changed? The fundamentals, certainly: the economy is better. But events, too: Obama has opened up a particularly large lead over Romney among women, which surely has to do with the Republican assault on contraceptive services for women following the administration’s compromise about the obligations of religious institutions to provide birth-control coverage.

The economy should loom particularly large in this election. After all, we’ve been living through the most severe economic crisis in eighty years. Although we are through the worst of it, economists are divided on how robust this recovery will prove to be by the fall. While it is true that the Federal Reserve and others have been surprised by the impressive jobs numbers of the last few months, very few economists so far are willing to say that the jobless rate will continue to fall between now and November.

Observers who are both pessimistic and optimistic tend to agree, though, that an unemployment rate at or below 8 percent—it was 7.9 percent the day Obama was sworn in and peaked at 10.2 percent in October 2009—would all but ensure Obama’s reelection. They base this figure partly on past election results, and it sounds overprecise for the future. An uptick that leaves the rate higher—say, at 8.5 percent or more—could mean big problems for Obama. Of course, momentum and the country’s direction figure into all of this too. Since 1976, Ronald Reagan is the only incumbent to win reelection with the unemployment rate above 7 percent. It was 7.2 percent during his reelection campaign in 1984, but it had been as high as 10.8 percent in 1982. Obama might be lucky enough to have the same outcome as Reagan if the sense of the people this fall is that a definite corner has been turned.

Such arguments suggest an election that will indeed be won or lost on the fundamentals. But I think there is an element of politics here, too. Romney made an error, in my view, in building his campaign message in the early days around the idea that Obama had failed so completely to deal with the economy. I remember thinking at the time: But what if things improve? What will he say then? Sure enough, he has had to change his tack, at times sounding unconvincing. On March 21, as the Etch A Sketch story was exploding, Romney said that George W. Bush and Henry Paulson, Bush’s last Treasury secretary, deserved the credit for the recovery instead of Obama. Neither polls nor many respected economists support this view, to put it mildly; and worse, Romney allied himself with the still-unpopular ex-president, whom the Obama campaign would love to hang around Romney’s neck.

Ultimately, while the economy is usually the most important factor, it is never the only factor, and there is too much that happens in elections that the fundamentalist argument cannot explain. Last year, most Americans had a favorable impression of Mitt Romney. The website Real Clear Politics keeps obsessive note of these matters, and maintains a Web page showing the results of some seventy surveys that have asked for opinions about Romney since last spring. He was in positive territory in every one of them last year. But in the twenty-two polls taken since mid-January, he has been viewed more unfavorably in every poll except one. What changed? It was, according to the polls, nothing to do with the economy. Instead it was the decisions he made, and statements he let slip along the campaign trail, for example about the satisfactions of firing people, or his lack of urgency concerning the poor, or his single-minded determination to kill, not to negotiate, with the enemy in Afghanistan.

And not only such slips but deeper commitments, even more than a strong economic recovery, may end up being Romney’s problem. This primary-season trial-by-fire from which he is finally emerging forced him—or at least, he and his people decided that it forced him—to take many other positions that may alienate independent voters in November. Eric Fehrnstrom, aside from being glib, was wrong about expressed views being ephemeral. Romney can’t retreat from endorsing Paul Ryan’s budget and its dark implications for Medicare. He can’t say that he was just kidding about supporting the recent Republican congressional bill that sought to give not just religious institutions but any employers the right to deny contraceptive coverage on moral grounds, or about his vow to defund Planned Parenthood.

He can’t back away from a tax proposal designed to placate the far right, a plan that makes Bush’s 2000 proposal look positively generous to the middle class. He can’t renounce his support for Arizona’s harsh immigration laws. He can’t magically undo having opposed the auto industry bailout. Unforeseeable events could all break his way. And Obama, too, will face some difficult political challenges. However the Supreme Court decides the health care case, there are risks for him: if the Court overturns the individual mandate (or especially the entire law), he will be dealt a terrible political blow; while if the Court upholds the act, this would energize the right-wing voting base more fully than anything Romney could do.

A retreating economy gives Romney a chance. If it turns sour, he’ll have his shot at victory. But he’ll have to be a much better politician than he’s been during the primary—and Obama a much worse one than he was in 2008.

—April 11, 2012

-

1

I reviewed both the Krugman and Bartels books in these pages. See “The Partisan,” The New York Review, November 22, 2007, and “How Historic a Victory?,” The New York Review, December 18, 2008. ↩

-

2

Crown Business, 2012. ↩

-

3

This line came from Perry’s television ad called “Strong,” which made its debut in Iowa on December 7, 2011. It has become, as measured by the number of viewers who have clicked the “dislike” icon that appears below every video clip, one of the most hated ads ever put up on YouTube. ↩

-

4

See John Sides, “Would an ‘Etch- a-Sketch’ Attack Actually Work?,” themonkeycage.org, March 22, 2012. ↩

-

5

See Nate Silver, “Models Based on ‘Fundamentals’ Have Failed at Pre- dicting Presidental Elections” on his FiveThirtyEight blog at nytimes.com, March 26, 2012. ↩