Private Collection/White Cube/Prudence Cuming Associates

Damien Hirst: In and Out of Love (White Paintings and Live Butterflies), 1991. As Julian Bell writes, ‘On a central table, the butterflies have been supplied with bowls of orange and pineapple chunks steeped in sugar, and the mixture’s fermentation accounts for their languor.’

One reason to visit the Damien Hirst retrospective at London’s Tate Modern is to meet the drunken butterflies. They are in a two-room installation entitled In and Out of Love. In its first room you see a few dead butterflies randomly stuck onto a group of big canvases that have been gloss-painted yellow, purple, pink, and so on, like a jumble of xylophone keys. Then you pass through PVC curtains into a bright and humid gallery where dozens of live specimens, of tropical origin, woozily waft through the air. Their dark silhouettes, passing you by, flash iridescent blues, vermilions, and lime-greens.

Around the walls here are further canvases, blank but for pupae that have been stuck to them and that have left stains where they have hatched. On a central table, the butterflies have been supplied with bowls of orange and pineapple chunks steeped in sugar, and the mixture’s fermentation accounts for their languor. Some settle on the floor just where your foot would tread; others on your clothes and hair. “Shall I remove them?” a Tate employee discreetly inquires, stepping forward to pinch them free. With your fellow visitors you share a certain silenced wonder, a certain social awkwardness.

The first room is easily forgotten, but the feel of this second is bemusing. There is the stimulus of encountering these specimens of extravagant beauty. To call their beauty “natural” feels not quite right when the display is so much an affair of importation, of metropolitan fantasy. Yet in their bumbling, drifty way, these butterflies follow natural processes, growing, reproducing, and dying as all animals do, including ourselves. Like us they have their own purposes: they have lives. Is it odd for lives to be specimens? Is it wrong to encounter beauty this way? After all, few of us would single out for condemnation—among all the ways in which humans exploit nonhumans—the insectarium in the zoo.

Ah, but here there are no descriptive labels, no “Morpho amathonte, native of Colombia” and so on. Instead we are left with a caption, “In and Out of Love,” requisitioning the butterflies for some metaphor about our emotions: how a curtain’s twitch, presumably, can revert us from the glamorous and sensuous to the dry and apathetic. Fine words in the press handout about “reputable” suppliers and “a comfortable environment” can’t quite dispel my sense that these creatures shouldn’t be thus co-opted as conduits for a person’s self-expression. Yet why should I prefer to set their lives to the service of science, rather than that of art?

The two-room piece at the Tate recreates an installation that Hirst originally devised in 1991. Its immediate predecessor, entitled A Thousand Years, has likewise been reactivated. Here the insects are behind glass and anything but exotic: flies in their hundreds, trapped in a garage-sized vitrine with an interior box shelter in which their maggots hatch. On the floor lies their food, the head of a freshly killed cow. From the ceiling dangles their fate, the chill UV striplights of an insect-o-cutor, into which they are drawn and die. I stand outside watching the process, which is full of strange fascination: the sudden swarmings of the flies, the way their dead bodies accumulate, the winding puddle of blood that has welled from the cow’s neck over the gallery’s oak floor. I sense the closedness of the cycle—and for a moment I am inside there, with the flies, caught up in a kind of grisly living poem. Then a detail returns me to spectatorhood: the way the blood trail concludes with a tiny island drip, like the dot of an exclamation mark. Yes, it is strong and stirring, this experiment in transgression, but where do those qualities shade into sheer preciosity?

Damien Hirst seems to share my uncertainties, talking in a catalog interview about the first time he put together A Thousand Years, back in 1990. He tells a good story about frantically escaping from the vitrine before the flies could follow him, then getting taken aback by what he’d done:

I’d never even considered the implications of killing things for art, really, it was just all on paper, all worked out in drawings. And then as soon as I’d got out I bolted it shut, it was the first time I’d ever made anything that had a life of its own, or had an uncontrollable life, or something that I had no control over. I had a sort of Frankenstein moment of “What the fuck have I done?” And the first fly got killed, and I was just like, “Oh, fuck.”

Good question: What has Hirst done? This retrospective, devised by the Tate in conjunction with the forty-six-year-old artist, offers an opportunity to take stock of a long-rumbling brouhaha. Since those insect installations established his name, over twenty years ago, as gangleader of the so-called “Young British Artists,” Hirst has rarely been out of the news. Via many pranks and party nights, the image that journalists have dealt in has morphed from brilliant brat to plutocrat. The latter status was cemented in September 2008, when Hirst held an outrageously successful auction of his work at the very moment of the Lehman Brothers default.

Advertisement

But to step inside Tate Modern is to let economics make way for palpable, walk-roundable phenomena. Instead of sums with multiple zeros, we encounter physical objects with demonstrable holes. The question about the middle-aged Damien Hirst becomes once again the question that visitors to his now legendary undergraduate exhibition “Freeze” had to ask themselves: the basic, default question, in fact, about art. Someone is urging me that these items are interesting to look at. But do I feel that they are interesting to look at?

Presenting those flies and butterflies, Hirst flexes his characteristic strengths, which are those of an art director. He has the capacity to dream up punchy, innovative visual propositions, certain to catch attention in the gallery much as Oliviero Toscani’s Benetton billboards used to catch attention in the street. This focusing power did much to mark Hirst out in the 1990s London art scene as a new sensibility, responsive to a quick-grabbing, instantaneous culture of spectacle. With it have gone executive gifts. Hirst knows how to get the right people together to realize his concepts and how to lead them from the front. Michael Craig-Martin, Hirst’s tutor when he was at London’s Goldsmiths College during the late 1980s, describes him as “a perfectionist, giving absolute consideration to every detail of his work.” Hirst may set little store on doing things with his own hands, but he certainly thinks with his own eyes. It is all a question, he has argued, of what happens when his concept is physically realized in the gallery. Once there, “If it looks good, it is good.”1

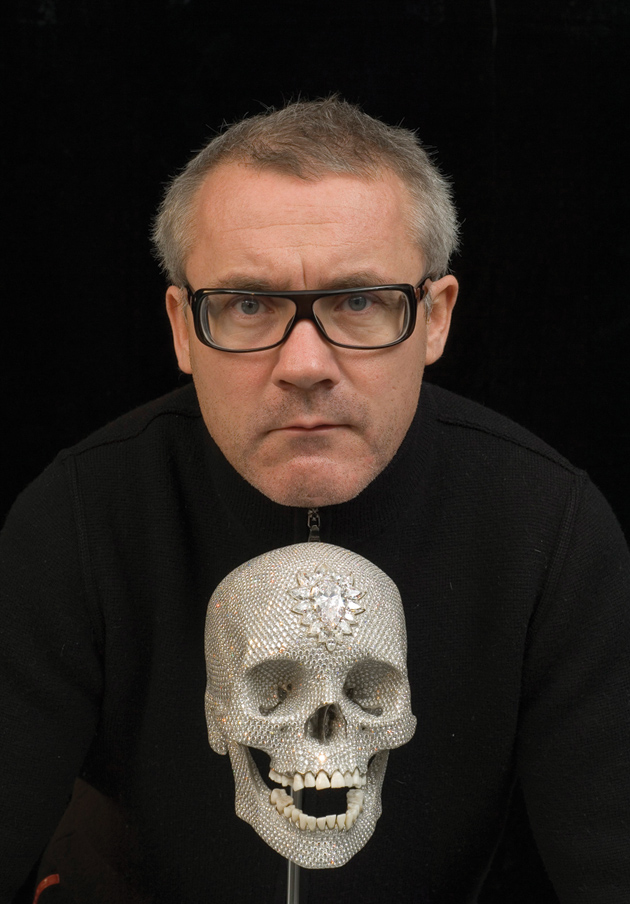

Literally the most dazzling proof of that contention is For the Love of God, the diamond-studded platinum skull he produced five years ago on an outlay of £14,000,000. Lit up in a darkened, heavily secured separate chamber, away from the main show, it is a disarmingly delightful spectacle, rainbow-twinkling, blithely grinning: a vulgarity so transcendent it gives vulgarity a good name. Hirst’s popularity has always been reliant on his wit, and celebrating the object that will always prompt our mortal fears and forever mock them, he has surely delivered his best one-liner, his own form of masterpiece.

The galleries upstairs survey various lines in visual invention Hirst came up with prior to that recent coup de théâtre—most of them originated around the turn of the 1990s, the time when he first arrived. The procedure of sticking butterflies to canvases gets extended, generating outsize hieratic wall hangings. Not only dead flies but dead fish, sheep, and cattle get encased in glass boxes, not to mention a dove. Another form of snuffing out is embodied in a line of cigarette-butt-based exhibits. Glass cases also feature in numerous Hirst pieces that employ pharmaceutical products and surgical equipment. Alongside them on the walls hang white canvases dotted with evenly spaced spots in many colors, and a few that have been splashed while spinning with mechanical jets of gloss paint.

An imposing professionalism dominates. The mind’s eye, or the mind’s hand, may come away rebuffed by the long shiny expanses of glass, gloss, and steel. Resistant also, perhaps: you might complain that just as living creatures belong in zoos, not galleries, executive attitudes belong in business and government, not in artists’ studios. But I think you would be clinging too hard to your sense of decorum. Never mind whether or not these experiences feel like “art.” Just stick to the question: Do they feel interesting?

I am leaning on the criterion that Donald Judd used when he sketched out the new aesthetic that would get known as “minimalism” back in 1965. “A work needs only to be interesting,” he wrote, asking viewers to focus on the boxes he’d constructed, designating them “specific objects.” “The thing as a whole, its quality as a whole, is what is interesting”—not the illusionism, the imagining of bodies and symbols, that dogs the painting tradition and is “one of the most salient and objectionable relics of European art.” 2

Advertisement

Hirst comes across as quite an adept second-generation follower of Judd in the show’s opening room, which contains work done when he was in his early twenties, fresh in London from a working-class childhood in the north. A kitchen cupboard, a row of cooking pans, and a concatenation of cardboard boxes get daubed with bright gloss colors and become new sorts of things to look at. A board leaned against the wall—his initial, crudely handmade spot painting—provides another. But from this point, Hirst followed Judd into a fascination with hands-off fabrication. His tank with pickled shark from 1991, entitled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, started out from “an idea that you can get anything over the phone…. I actually wondered if there was no limit to it”3—a point demonstrated by ordering the specimen for his original London exhibit from a shark-catcher in Australia. (The replacement carcass currently on show presents the all-too-physical palpability of decay to the eyes of someone observing: I can’t but notice all the taxidermist’s pins straining to hold him together.)

Three decades separate Judd’s “specific objects” and Hirst’s own fabrications. Many “role models” stand between, perhaps most obviously Jeff Koons. It was from Koons’s mid-1980s exhibits in New York that Hirst adopted the motif of the vitrine, the self-important glass box, that features so heavily at the Tate. The sensibilities of both men are much indebted to minimalism, and yet both have crucially turned away from its precepts: they have yearned to bring back content to art, restoring that “objectionable” quotient of symbolism. For Koons that has involved dealing in cutesiness and porn with reference to “the mass of people”4 and to what they really want: to themes you might dignify as “society” and “desire.”

Hirst, equally keen to be meaningful, has pretty well avoided each of those large categories. Not wholly: In and Out of Love constitutes his own modest allusion to sensuality, and the room installation Pharmacy, with its shelves upon shelves of assorted pill packets, backhandedly comments on the negative community formed by our shared ailments and blind trust in science. But the prescription on the absent pharmacist’s desk is from London, while his foodbag is from New York: it’s a generic, fatalistic visual poem, with no bite on any particular place, time, or politics.

For Hirst’s chosen task, as the shark and diamond skull indicate, is to coin visual aphorisms on the nature of life and death, at once recklessly bleak and brimming with sheer cheek. He lays claim to a style in disillusion, jocular and savage, for which you could find English correlatives in Philip Larkin’s later poetry or in Monty Python’s Life of Brian. Yes, beauty is what matters and beauty is what my art subscribes to, Hirst declares: look at all those iridescent wings, look for that matter at all those perfect, gleaming panes of glass! Yet by the same token—for beauty is at root a response to it—there is mortality. A truth that we can only grope for with sad laughter: look at this poor pickled lamb, frozen in mid-skip! Or through gross mock-aggression: regard this poor cow and poor calf, each swaggeringly chainsawed in two!

What is remarkable, as the art historian Thomas Crow points out in the exhibition’s catalog, is that with his wry, heavyhanded, sometimes grisly take on eternal verities, Hirst has become a people’s artist on a scale far exceeding that of Koons, the impresario of busty babes in porcelain and giant shiny rabbits. “Despite his strenuous efforts to fashion a crowd-pleasing, populist body of work, Koons remains a name recognized largely among self-selected art followers”; whereas the name of Hirst is now “virtually synonymous with the art boom of the 2000s,” spearheading a vast extension of the international audience for contemporary art.

Crow probes the factors leading to these differing outcomes. “The American artist assumes that the mass media cannot be moved, so adopts a defensively superior attitude towards the whole popular realm.” In London, however, with its “overheated media concentration,” there might be an opportunity for fine art to bend the narrative to its own ends, “provided that its procedures and processes are realistically regarded as so much expedient packaging.”

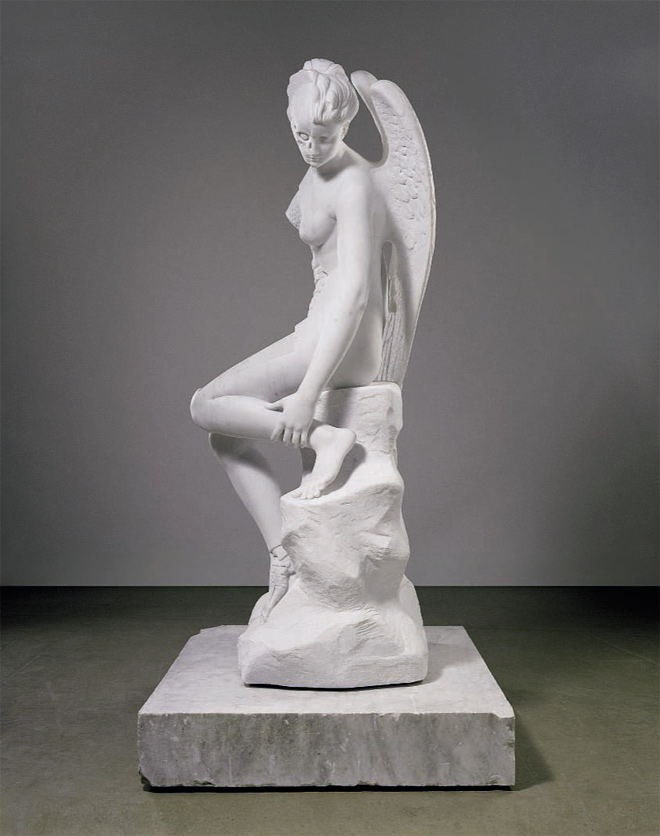

So it was that in 1990 the boldness of Hirst’s personality, along with the enormous flair for innovation that he then possessed, attracted the respect of Charles Saatchi, by far the most important patron of contemporary work in London’s “media concentration.” Their ensuing alliance gave this strategically streamlined art an exceptional breadth of license in which to operate. It feels as though Hirst has been able to make pretty much whatever he wanted for a very long time. His career has settled into a pattern familiar to rock stars, torn between whether to keep trading on early hits or to try to break into fresh markets. He has certainly been highly productive—at least once, I’ve suggested, to memorable effect. But the diamond skull apart, most of the new ventures have been eminently forgettable. The Anatomy of an Angel, a classicist marble statue of a female nude opened up in anatomical cross-section, is the exhibition’s nadir: it assaults a genre far too dense in accumulated meanings to be pierced by this style in wit.

Having so long depended on his fears of death for creative stimulus, Hirst has more recently tried to cook up his conflicted feelings about God toward the same end: but his vitrined Holy Ghost and butterfly-wing mandalas are whimsical conceptions, neither searingly blasphemous nor stoutly materialistic. And then, near the show’s end, he attempts, for once, an autobiographical note. Or so I read a gallery that reprises his greatest hits—the lepidoptera, the pills, the cigarette butts, colored spots, and diamonds—but all framed against backdrops of gold. Ah, pity me for my Midas touch!

Hirst is a large enough personality, however, to acknowledge the problem his career’s form presents. In a catalog interview with Nicholas Serota, the director of the Tate, he comes across as a man of loyalties and devout artistic admirations, readily offering an afterthought to that anecdote about sealing up the insects, twenty-two years ago:

The fly piece was the most exciting thing—still is, possibly—the most exciting piece I made. I still don’t really understand how you get to those moments. It’s instinctive; you can’t really control what you do. Lucian Freud said to me, “I think you started with the final act, my dear,” or something like that. And in a way I think he was right.

For much of the time, when Hirst hasn’t been able to “get to those moments,” he has opted to persist obstinately in pursuing intuitions glimpsed back in his youth. As a result, there are large swathes of this exhibition that are not exactly bad in the way that Angel is bad, but neither are they particularly rewarding to look at.

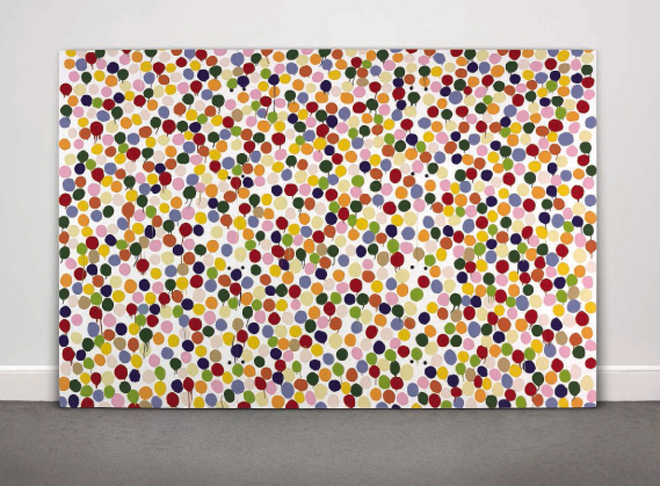

The projects in question stem from Hirst’s early attention to minimalism. Perhaps, he proposed, you could cover canvases with systematically positioned spots of color, and this would be enough: this would, quite simply and self-sufficiently, offer beauty to the eyes. And so it does, albeit mildly, a couple of times, at first. But that proposal proved too modest: the “spot” procedure must be maximized, in a series meant to run on forever. (Besides, these easily stackable products proved Hirst’s easiest items to sell.) The resulting barrage of inanition is matched by the tedium of the pharmaceutical displays, which continue from gallery to gallery. Again, a notion from Judd about coming to terms with actual, orthogonal, industrial products lurks somewhere in Hirst’s obsessive packet-collecting, but it’s confused by his symbolic aspirations. Hirst’s wit is sometimes more alive verbally than visually: to give eight of these glazed cupboards titles after Sex Pistols songs doesn’t turn them into vivid experiences.

The problem can be expressed spatially. Hirst has a good instinct for what will dominate a gallery, if the exhibit is set on its floor. But galleries also have walls, and these daunt him. Hanging stacked cases and arrays of spots and insect wings is a way of deflecting the demand that gallery walls customarily make on an artist. For what principally drives Hirst (and again, we have his own freely offered word for it) is a fear not of death but of painting.

Long before he glanced at Donald Judd, Hirst was looking up to Britain’s own master of the portentous designer-macabre, Francis Bacon. This lifelong reverence has coexisted with a terror at blank canvases and the endless choices they present, a neurosis best negotiated by hands-off, art-director tactics. It remains the case that, as Hirst said in 2001, “there’s one kind of art, and it’s painting. Everything else is a step away from that, and it all points back to that.”5 His poor-little-rich-kid problems are not my concern, but in this light I feel there was something touching (as well as pompously foolish) about his exposure, three years ago in a London museum, of some recent, timid, hand-painted homages to Bacon. They met with universal ridicule, and have not reappeared at the Tate.

Such is the strange position of this front man for the era of installation. Hirst is clearly a historically significant artist—not least in his own earnest striving for life-and-death significance. The conjunction of that striving with a media-savvy, image-grabbing sensibility has delivered pieces that, at their strongest, set thoughts jangling concerning our value systems. (I continue wondering about those butterflies. It’s as if life were one positive charge and painting another, but if you force the two together, substituting a flapping wing for a brushstroke, some kind of repulsion occurs.) This is merely to salute the artist as a symptom of his age: it is not a statement of taste. Personally I find that it is the small, intimate, ephemeral significances that go missing in the broad range of Hirst’s bombast.

I only see them come alive in one line of image production, and that half-inadvertently: the conceit of the extinguished cigarette. “From the point you light one to when you stub it out, it’s death,” Hirst paraphrases, ever helpful to his exegetes. Nowhere does it feature more poignantly than in a piece from 1991 named The Acquired Inability to Escape. A packet of Silk Cuts, a Bic lighter, and a filled ashtray sit on a white Formica table, at which an empty office chair has been drawn up: a seven-foot-high vitrine immures them, and through an internal dividing pane the chair faces a yet more constricted, entirely vacant glass box. Every aspect of the ensemble is severely, formally exquisite, so that one can imagine it as a memorial monument to the desperate habits of the previous millennium. Indoor smoking: now that’s truly a dying art.

This Issue

May 24, 2012

How to End This Depression

The Rapture of the Silents

-

1

Interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist in Beyond Belief: Damien Hirst, exhibition catalog (London: Other Criteria/White Cube, 2008), p. 32. ↩

-

2

Donald Judd, “Specific Objects” (1965), in Art in Theory, 1900–2000, edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Blackwell, 2003), p. 813. ↩

-

3

Hirst interviewed in Damien Hirst and Gordon Burn, On the Way to Work (London: Faber and Faber, 2001), p. 45. ↩

-

4

The phrase Koons uses in a 1986 roundtable discussion, collected in Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory, p. 1083. ↩

-

5

Hirst interviewed in Hirst and Burn, On the Way to Work, p. 68. ↩