Talking to a class at the University of Mississippi one day late in his life, William Faulkner remarked that his cogenerationist Ernest Hemingway lacked courage as a writer, that he had always been too careful, never taking risks beyond what he knew he could do, never using “a word where the reader might check his usage by a dictionary.” The remark, quoted in a university press release, was picked up by the wire services and eventually made its way to Hemingway, who was outraged that Faulkner had questioned his courage. Faulkner then had to write a letter of apology and explain that he never questioned Hemingway’s physical courage, but only his courage as a writer who never went “out on a limb” or risked “bad taste, over-writing, dullness, etc.” Hemingway’s hurt seemed to have been assuaged, the criticism applying only to his life’s work.

But what did Faulkner mean? Certainly more than a matter of not using words from the dictionary. We might be tempted, considering As I Lay Dying, his novel of 1930 about a Southern family of poor whites narrated by its members and their neighbors, its events refracted through multiple points of view, that Faulkner was referring to Hemingway’s reliance on standard fictional conventions—the simple declarative sentence, the single narrative voice, and a linear sense of time. But we would be only half right.

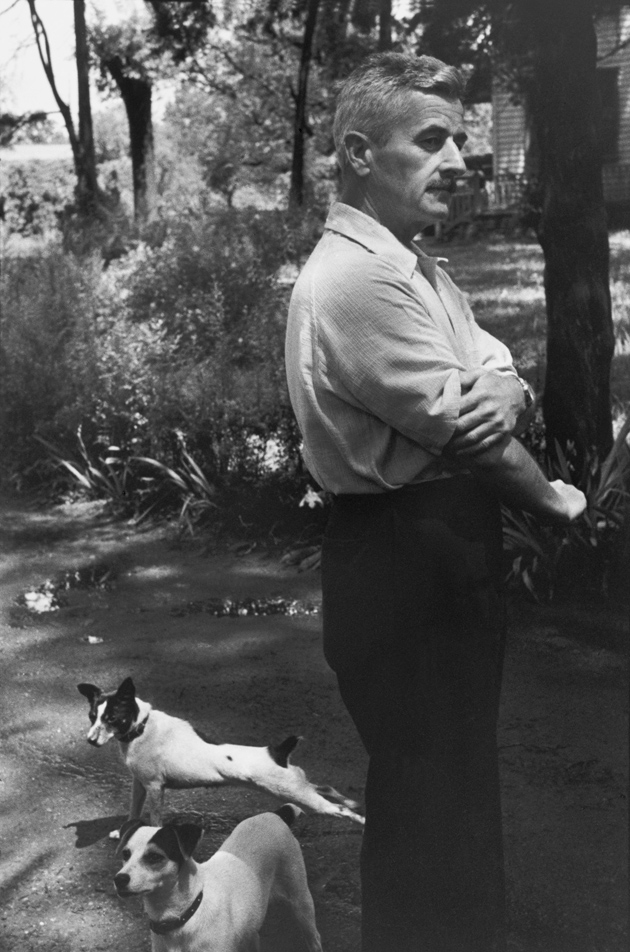

Faulkner had never lived as rarefied an existence as Hemingway, a man who organized his life around pursuits—hunting, fishing, writing, war reporting. Faulkner’s life was messier, less focused, a struggle from the beginning to make enough money to survive: he was a school dropout, and worked at various jobs—postmaster, bookstore clerk—and he held down the midnight shift in a coal-fired power plant, where, as it happened, he wrote most of As I Lay Dying. He was an air cadet in Toronto when World War I ended and unlike Hemingway had to pretend to the combat experience that had eluded him. He wrote poetry before he ever considered fiction, fell in love with a woman who married someone else, bought a house in some disrepair and did all the renovations himself, lost his brother to an airplane accident for which he felt responsible, and became a heavy drinker presumably to deal with the intensity of his writing life.

But it is possible that the way writers live can find its equivalent in their sense of composition, as if the technical daring of Faulkner’s greatest work has behind it the overreaching desire to hold together in one place the multifarious energies of real, unstoried life.

And so now we are here with the Bundrens, a down-at-the-heels family of dirt farmers in Yoknapatawpha County. Who lays dying is Addie Bundren, the mother. She listens to the “chuck, chuck” of the adze as her son, Cash, fashions her coffin outside her window. Addie’s husband is Anse, who complains about the burdens that life has put upon him. The other children are Darl, suspected of being mental; Jewel, he of the white eyes and the horse he loves and abuses; Dewey Dell, the only girl in the family, seventeen and secretly pregnant; and finally the little boy Vardaman, who will, after catching a fish and gutting it, declare that his mother is a fish.

The reader will find the members of this family composing the book out of their stream-of-consciousness monologues, the presence of each of them in the minds of the others being the author’s means of delivering the specificity of their characters and forwarding the action. Functioning as chorus are the various friends and neighbors, including the local veterinarian, who attend to this impecunious family during the trials it brings upon itself. And when Addie Bundren dies, having just once raised herself to the window to look at her coffin, her presumed desires direct the action of the rest of the book, for she has chosen to be buried among her “own people” in the town of Jefferson, forty miles away. Though the family is warned that the weather is bad and the river between here and Jefferson has flooded and the bridge is down, and that the trip in their mule-drawn wagon will be hazardous, Addie’s husband Anse, a spiritless man in faded overalls, physically weak but domineering in his passivity, insists that they must follow Addie’s wish, taking her body to her chosen burial ground in Jefferson, the same town where he will, not so incidentally, get himself the pair of false teeth he has wanted for a long time.

And so the family’s perilous journey begins, the coffin in the wagon bed, and the fierce, rarely speaking brother Jewel on his horse behind the wagon. And if the reader wonders about the name Jewel, ordinarily that of a girl, Addie herself, speaking from her casket, like some of the speaking dead in a poem of Thomas Hardy’s, informs us that Jewel’s father is not Anse but a local preacher, and so Jewel is the one she loves, and the others she regards as Anse’s children, born in the rage of her duty as the Christian wife of Anse, whom she has despised most of her married life.

Advertisement

We begin to understand the qualities of the family Bundren—that name, too, somewhat allusive, perhaps suggesting an alliance rather than a family, because for the most part, under the stubborn domination of their cunningly passive father, and given their lives of permanent crisis, the siblings are attentive to one another in the dutiful and not always sympathetic way of kin bound together for the purpose of survival.

This is a family of groundlings tied to the land, subject to the elements, to the seasons, and to natural disasters. Their lives are unmediated by culture, schooling, or money. It is as if the universe pressing down on them is created by themselves.

Faulkner does a number of things in this novel that all together account for its unusual dimensions. Nothing is explained, scenes are not set, background information is not supplied, characters’ CVs are not given. From the first line, the book is in medias res: “Jewel and I come up from the field, following the path in single file.” Who these people are, and the situation they are dealing with, the reader will work out in the lag: the people in the book will always know more than the reader, who is dependent upon just what they choose to reveal. And at moments of crisis and impending disaster, what is happening is described incompletely by different characters, so as to create in the reader a state of knowing and not knowing at the same time—a fracturing of the experience that has the uncanny effect of affirming its reality.

Of course Faulkner was not alone in his disdain of exposition. Though he didn’t begin to write screenplays for Hollywood until some years after this novel was written, film had been around all his life and it was film that taught him and other early-twentieth-century writers that they no longer needed to explain anything—that it was preferable to incorporate all necessary information in the action, to carry it along in the current of the narrative, as is done in movies. This way of working supposes a compact between writer and reader—that everything will become clear eventually.

Time is continuous in this book, which means nothing that happens in the course of events will be incidental. Addie dies and the family loads her coffin in their wagon and sets off for Jefferson. At this point the reader may realize that it is a habit of some family members to see things as something other than what they are. It is Darl, the major narrator of the novel, who most often is given to this: “Below the sky,” he says, “sheet-lightning slumbers lightly; against it the trees, motionless, are ruffled out to the last twig, swollen, increased as though quick with young.” Or when his mother, Addie, has just died, he sees “her peaceful rigid face fading into the dusk as though darkness were a precursor of the ultimate earth, until at last the face seems to float detached upon it, lightly as the reflection of a dead leaf.”

It is poets who make transformative observations that intensify life. Darl’s gift, his language of thought being far beyond the ability of his father or his siblings, suggests why they think he is touched. And Faulkner may be saying that Darl requires that diagnosis, or else how can he, Faulkner, get away with verbiage in such contrast with the diction of the common tongue?

For the other speakers, family members and neighbors, with the exception perhaps of the little boy Vardaman, have only country speech—serviceable and even primitively eloquent, but hardly with the gift of metaphor: “We never aimed to bother nobody,” Anse says to a town marshal. Dewy Dell says, “I’d liefer go back.” The oldest son, Cash, looking at the swollen river they need to cross, says, “If I’d just suspicioned it, I could a come down last week and taken a sight on it.” The remarkable thing is that the book’s two modes of discourse—its literary thinking and its common speech—are complementary. The inner and outer life run together on this perilous family journey—it’s as if the words themselves are shadow-lettered and given dimension.

Apart from its technical achievement, and the descriptive prowess here as in all of Faulkner’s major works, As I Lay Dying can be read as having been written in anticipation of the South’s cultural designation as the symbolic face of the Great Depression. Someone who knew the South, as Faulkner did, would not abide that sort of reductionism. There is no claim of social inequity in this novel; there’s barely a moment or two of compassion. Suffering is not seen as a moral endowment, nor is poverty seen as ennobling.

Advertisement

The Bundren family relationships are cruel. Darl, who knows Dewey Dell’s secret, speaks of her legs as calipers. Anse takes her abortion money to buy himself his false teeth. Anse also takes away Jewel’s beloved horse to trade for mules, his team having last been seen in the flooded river, their legs sticking into the air. And if consigning Darl to the state asylum will save the family legal trouble, no one thinks twice. Bundren family life, like the weather, like the land and the water, is elemental and merciless, especially so for the women. Dewey Dell and her mother Addie are the gender afflicted, the one stupid and sexually used in her youth, the other physically exhausted, bitter, and unforgiving on her deathbed.

As the family make their beleaguered way to Jefferson, with Addie’s corpse putrefying in a coffin that has seen too much time above ground, they are a procession for townspeople to look on with astonishment or disgust. Faulkner finds here, as he will in much of his survey of Yoknapatawpha, the elements of a Gothic story salted with ghoulish humor. At high moments of flood and fire a biblical suggestiveness is carried by the prose, but in the raw life here presented, the book is more often Shakespeare without the royalty—the Shakespeare of Pistol and Fluellen, Snug and Tom Snout.

Faulkner wanted to write a tour de force and he did. His famous claim is that he pulled it off in six weeks. His biographer, Joseph Blotner, says it was more like eight. The book would have been astonishing if it had taken eighty. It is a virtuosic piece, displaying everything that Faulkner has at his disposal, beginning with his flawless ear for the Southern vernacular. But this is an all-white novel set in Yoknapatawpha County. That alone indicates we are not reading a social novel with the urge to report. For this reason it stands thousands of miles from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. And considering Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road, which purports to deal with the same Southern backwoods culture, neither are the Bundrens subject to the disdain, mockery, and superior airs that the hillbilly Lesters of Tobacco Road endure from their author. As I Lay Dying does not look up to its characters, or down, but maintains them at eye level, where we sense that a scrupulous dispassion gives Faulkner access to the unmediated truth.

And so it is possible for us now to begin to understand what he meant in his criticism of his colleague Ernest Hemingway: not merely that Hemingway was technically undaring, but that, in thrall to the romance of the self, he had never tapped the human psyche to the depth of its raw existence, or written of characters not defined by the familiar constructs of social reality. As we read this novel, we see that Faulkner spoke with the authority of someone who had.