As the second year of medical school drew to a close, our education moved from lectures in the classroom to rounds at the bedside. We assumed the role of apprentices, expected to model ourselves not only on the clinical acumen of the senior physicians, but also on how they communicated with patients.

Each student followed a sequence of assignments to the different wards, and my first months were spent with the surgeons. Despite the grueling hours and heavy workload, the experience was exhilarating. I watched with awe as a woman’s chest was opened, exposing a gritty stenotic aortic valve, which was replaced with a functioning prosthesis. The procedure took many hours, and demanded a precise choreography of care among the heart surgeon, anesthesiologist, and cardiologist. As the last sutures were placed, the resident remarked how it was “a great case.”

While surgery offered the drama of dexterous skills, my next assignment, to internal medicine, prized broad thinking. The aim was to generate comprehensive lists of possible causes for the patient’s symptoms and physical findings, so-called “differential diagnoses.” It was like assembling a large jigsaw puzzle, but you did not receive the pieces all at once: rather, you had to guess which next piece to seek by ordering one diagnostic test or another—should it be a certain X-ray, or a particular serology, or a tissue biopsy? Then you evaluated whether the new piece of data fit and solved the puzzle, or whether more was needed to form a coherent picture. “Great cases” on the internal medicine ward were ample. I recall how our team of residents and students identified a rare form of malaria in a botanist with raging fevers who recently had returned from Africa, and discovered an overlooked lymphoma that was the cause of a patient’s kidney failure. After surgery and internal medicine, I was assigned to pediatrics, and there became frozen in my tracks.

Some of my day was spent in the outpatient clinic, where mostly healthy children arrived with sore throats or ear infections, and our prescriptions for acetaminophen or antibiotics were rewarded by a parent’s relieved smile. But the other part of the day was on the wards, among scores of children with incurable illnesses. There were listless babies with a dusky hue whose malformed hearts defied surgical repair, toddlers with cystic fibrosis struggling to breathe through airways encased in cement-like mucus, middle-schoolers with brain tumors that blunted their vision and unleashed violent seizures.

In the evenings, the images of these children could not be moved from my mind. I was unable to concentrate on the medical articles assigned for reading, or prepare presentations for the next day’s rounds. I could not summon the cognitive dissonance that allowed labeling a patient “a great case,” and had no capacity to marvel at the complex biology of a child’s disease. As I looked at these suffering youngsters and their anguished parents, all I felt was pain and loss. I realized that I had reached my limits, that I would not be able to function effectively as a pediatrician, to care competently for such desperately ill children, to stand in charge at their bedside without being overwhelmed by emotion.

Doron Weber’s Immortal Bird is the story of his son, Damon, born with a malformed heart incompatible with life, and cared for on the same pediatric ward where I was a medical student. The narrative is wrenching, and there were several times I had to put the book down. Not long after I finished reading it, I met a young pediatrician who directed the intensive care unit at her medical center. I asked how she balanced her mind and her heart, the need to think coolly while caring deeply. “You learn how to manage your emotions,” she replied. “And for the children who do not survive, I feel it’s an honor to have been with them at this point in their lives.”

Damon Weber was born with one rather than two ventricles in his heart. A complex surgical repair, called a Fontan procedure, was performed to allow adequate flow of blood to his organs, and for many years the repair succeeded. Under the watchful eyes of Dr. Constance Hayes, a pediatric cardiologist at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, Damon flourished. But when he entered eighth grade, his parents noted that he wasn’t growing well; despite a healthy and nutritious diet, his body had begun to lose vital proteins. Some 10 percent of children like Damon who undergo the Fontan repair later develop a syndrome termed protein-losing enteropathy, or PLE. The gastrointestinal tract leaks albumin and other vital proteins. This disturbs the nutritional and fluid balance in the body, so that growth is stunted and organs swell with retained water.

Advertisement

Doron Weber was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, worked in communications at the Rockefeller University, and now is at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation overseeing programs in the public understanding of science and technology. Shealagh Weber, Damon’s mother, is a psychotherapist. Both parents are conversant with medical terminology and Doron Weber in particular is able to tackle clinical research studies, identifying their methodological limitations and critically weighing their results.

“They think it’s something called PLE,” Shealagh says in a low, fraught voice. “He’s not keeping protein in his body.”

“Never heard of it…What’s the treatment?” I ask, assuming a new medication.

“Dr. Hayes says they’ll see if they can fix the problem in the cath lab or redo his original operation, but otherwise he will need a heart transplant.”

“What?” I shake my head in disbelief. “Hold on! How do we go from ‘He’s doing so well’ in one checkup to ‘It’s all falling apart’ in the next? Where did this come from?”

…I have one basic rule: if we can’t understand an issue or a medical approach makes no sense to us, it’s the doctor’s problem, not ours. No mumbo-jumbo. We must always know exactly what’s going on so we can help ensure the best decisions are made. The most capable physicians supply the clearest explanations—equally clear about what they don’t know as what they do—and only the mediocre take refuge in obfuscation or omniscience.

Weber is certainly right that a doctor’s skills in communicating clearly with her patients reflect her clinical acumen. But there is another dimension to the importance of providing comprehensive information. Much is made in the popular imagination about maintaining an optimistic attitude in the face of severe illness. Yet there is a key difference between optimism and true hope. An optimist believes that things will generally work out for the best. Life teaches that this often is not the case, and Doron Weber does not depend on an optimistic outcome in his son’s case. Rather, he seeks true hope by being clear-eyed and complete in his understanding of every potential clinical problem and pitfall. Only that way can he see a possible path through the looming risks and dangers. To be unaware or deny a possible complication or reversal leads to the complacency of false hope.1

Weber reports that Dr. Hayes did not inform the family that this serious loss of protein could one day occur in Damon’s case:

I cannot grasp how the same voice that has seen us through two open-heart surgeries and countless medical difficulties to the verge of young adulthood, the same voice that has bantered with us about skiing and schoolwork and Damon’s plays,…not once…breathed a word about the possibility of a new disease—which, if he has it, has been developing for some time—how this same voice could so suddenly change its tune….

If the leakage cannot be stopped, the patient will eventually “starve” to death. No one really knows what causes PLE—though many suspect a link to higher pressures in the heart—nor has anyone found a cure.

We learn that Dr. Hayes’s omission was not consciously intended, not meant to spare Damon’s family worry. She explains that she was “so encouraged by his tremendous success that I didn’t want to believe it myself.”

Here is the risk of emotion, when a caring doctor cares so much that affection can cloud thinking. I have been in the same place as Dr. Hayes. My empathy for an exhausted, feverish cancer patient caused me to omit an intrusive physical examination. Taking a shortcut to spare him discomfort, I missed an abscess deep between his buttocks. The patient soon went into shock from sepsis. Fortunately, he survived my error.

Medical mistakes have been studied over the past two decades. Newspaper headlines feature cases of surgeons operating on the wrong limb, of incompatible blood products given to recipients, causing a life-threatening reaction to the transfusion. Initially, the focus was on such technical and logistical errors. Much progress has been made in implementing systems based on so-called “cockpit rules,” with multiple checks on each step of administering anesthesia or accounting for surgical instruments, so none is left in the body after an operation. But more recent research indicates that the majority of medical mistakes are not caused by technical errors but are due to thinking traps.

Cognitive psychologists have identified an array of biases that we employ in making judgments under conditions of time pressure and uncertainty. For example, “anchoring” occurs when we latch onto the first bit of clinical data, skewing our thinking. Anchored on a premature conclusion, we fail to consider the full range of possible causes for the patient’s condition. These pitfalls account for most cases of delayed or incorrect diagnosis.2

Advertisement

As Weber recounts the unfolding struggle to combat PLE, he reveals Damon not only as a patient but as a person. The teenager is a student with a keen mind who gained acceptance into one of the most competitive public high schools in New York, a talented actor who readily masters his roles, and the leader of a collection of fun and quirky kids. David Milch, the screenwriter, is a friend of the family and creates a part for Damon in the HBO series Deadwood. Despite blistering California heat during the shoot, the young actor displays the determination and stoicism that characterize so many children who are afflicted with maladies from an early age.

In this book Doron Weber does a great deal of kvelling, the Yiddish term for effusive parental praise for a child’s accomplishments. Weber also portrays Damon’s remarkably mature grasp of his condition. While watching a TV program about John Kennedy, Weber tells Damon how, from a very young age, the future president suffered from a series of “grave ailments” including scarlet fever, colitis, back injury, Addison’s disease, weight loss, and sleep disorders. JFK took ten to twelve medications a day and was getting six daily injections for his back pain. Whenever Doron speaks to his son, he uses the nickname “D-man.” “Sound familiar?” he asks Damon.

“It’s inspiring to see what people can accomplish despite early setbacks. How overcoming illness and adversity builds character…Hey, D-man, maybe one day, you’ll be president.”

Damon gives me a look that shows how absurd he finds this, but I persist. “Maybe that’s what all this is about. Forging your character in the crucible of suffering. You’re being tested…and you’d make a damn good president!”

“Thanks, Dad, I appreciate the vote of confidence,” Damon replies tartly, “only I don’t want to be president.”

Then there is the teenager’s own wry and lively writing that fills the blog he kept as he struggled with his deteriorating condition:

Yankees slaughter Red Sox first three games but Red Sox come back to win four consecutive games make the world series and baseball history. Due partly to a player who happens to bear the name of Damon.

Which just goes to show you boys and girls: it ain’t over till it’s over.

It ain’t over till its fuckin over.

—From Damon’s blog, fall 2004

Damon’s humor mixes with a growing self-awareness that his time may soon end if his clinical condition cannot be remedied:

I’m kinda in a weird place right now but that’s life and this is most certainly not Wallgreens! I feel like the tapestry that is my life is unwinding and all the threads are blowing in different directions threatening to fly away completely. I want to reach out and grab them and secure them again but if I try for one thread, I am forced to loosen my grip on another and I may lose it entirely, so I just have to sit tight and watch the pieces flying off. And then of course there’s that one thread whose color I desperately need to change, as it would make the tapestry much more beautiful and worthwhile. But then of course that thread might not be able to change colors and in trying I might turn it an ugly brown (like when you’ve mixed too many paints) and if that thread became brown, the entire tapestry would become ugly and not worth looking at, and maybe even not worth working on, I’m not sure. And that was my bad metaphor 4 the day.

Damon first undergoes a fenestration procedure, a window punched in his Fontan repair, done via a cardiac catheter, and has a temporary respite from the ravages of PLE. Then he has transient benefits from injections of the anticoagulant Heparin. But it soon becomes clear that only a heart transplant can address the problem by normalizing the disturbed flow of blood in his body.

The Webers have to make an agonizing decision: take on all the immediate risks of the surgery and then lifelong immunosuppressive medications to prevent rejection of the donor organ, or continue with less drastic interventions, holding on to the tenuous hope that one day a safe, scientifically based therapy will be found for the malady. Ultimately, with Damon’s full assent, the Webers choose heart transplant. Damon’s care is transferred from their longtime pediatric cardiologist, Dr. Hayes, and the catheterization expert, Dr. Hellenbrand, to a new team of transplant specialists. Weber uses pseudonyms, Dr. Davis and Dr. Mason, for these doctors, and it soon becomes apparent why.

“How long will it take you to find me a new heart?” Damon asks.

Dr. Davis explains that transplant patients are classified under three categories: status 1A, for those in the most urgent need; status 1B, for those with the second-highest priority; and status 2, for all other “active” patients on the wait list.

“Damon, since you are classified a two, the lowest priority, you’ll have a six-to-twelve-month wait, though it could be sooner—being under eighteen years of age may work in your favor—or alternatively, even later. No one can predict.” Dr. Davis smiles.

As I hear this, something nags at me. I recall that Dr. Bruce Gelb [a friend of Doron Weber], in one of his asides, had mentioned Damon could qualify as a 1B due to his small size, under the criterion “failure to thrive.” I hadn’t fully understood what Bruce meant at the time, but his words come back to me now, and I ask Dr. Davis about them.

“No, that’s not true. Damon is a two,” Davis says. “You’re mistaken.”

“I’m sure you’re right,” I reply, “but I’m surprised a leading cardiologist like Bruce Gelb, who’s a pretty sharp guy, would make such an error.”

“I can’t answer for him but I know transplants, which is my specialty!”

“Of course.” I let it drop. I don’t want to risk further antagonizing Dr. Davis…and it’s possible I’m the one who made the error or misremembers.

Dr. Davis continues to instruct Damon about his big day in a clear, cogent manner, but she seems beset by second thoughts and turns to her assistant.

“Erica, could you go get me the big manual on heart transplantation?”

Moments later, Erica returns with a tome. Dr. Davis tears it open and races through the pages, searching with her index finger like an avid medical student.

“I’m not sure”—Dr. Davis finally looks up from the manual—“but you may have a point about Damon’s status. I’ll research it more and get back to you.”

I’d already given Dr. Davis the benefit of the doubt, so this fumbling uncertainty unnerves me. We leave feeling uneasy about what’s going on, obviously hopeful for a status revision in our favor but also worried about what such a revision might signify.

The next day we get a fax from Columbia informing us that Damon’s wait-list status has been officially changed from a 2 to a 1B.

It’s the difference between being high priority and low priority, between waiting for a few weeks or up to a year. It could also mean the difference between life and death.

Damon’s case seems to spin further out of control, and although the reader is aware of the ultimate outcome, Weber’s riveting retelling keeps us in the moment:

We’re biding our time now and praying that no more mishaps occur. One morning, the nurse brings Damon a 1,200 mg pill of ibuprofen instead of magnesium—after everyone has warned him that he must not take any ibuprofen. This time it’s Damon, more alert now, who catches the mix-up and sends the toxic pill back. He talks to me about it repeatedly.

“Dad, she gave me the wrong pill! If I hadn’t noticed, I’d have been in big trouble…We have to watch everything, it’s just like you said!” He’s shocked and looks at me with new understanding. I’m known as the barking dog by my family, and God knows what else by the hospital staff, and now Damon sees firsthand how critical our vigilance is.

After what appears to be a successful heart transplant, Damon becomes increasingly fatigued, his platelet count falls, and his oxygen levels plummet. A biopsy of his new heart does not show his body is rejecting it. But one specialist still thinks this explains his deterioration, and she prescribes a higher dose of immunosuppressive medication. If the doctor’s presumption is right, the treatment could potentially save Damon’s new heart and his life.

But the assumption turned out to be wrong. Rather, Damon is found to be infected with Epstein-Barr virus, which is innocuous in healthy teenagers, causing infectious mononucleosis. But in someone like Damon, whose immune system is medicated to a low level, the virus can cause what is called “post-transplant lympho-proliferative disorder,” or PTLD. Weber describes the significance for Damon:

PTLD is a very serious condition in which the lymphocytes, white blood cells normally involved in the body’s defense system, multiply rapidly and attack the vital organs. It’s one of the three major threats for heart transplant patients, ranking just behind rejection and infection, and its consequences can be severe.

Damon succumbs to PTLD. (The Webers later decide to sue the pediatric cardiologists who oversaw the transplant, as well as the hospital.) Doron Weber captures in tight language but a small fraction of the pain shared by all who loved him:

Damon Daniel Weber officially died on March 30, 2005, except no one that you love dies once or ever stops not being alive, and nothing you do can change what happened or bring back what’s gone.

The narrative closes with a lyrical description of Damon at the age of three, delighted by falling snow in Prospect Park:

Damon is beguiled and transfixed by the miracle of snow. He marvels as the clustering, diamond-shaped flakes settle over the ground and the trees, transforming all around him into an enchanted white playground. He pumps his arms in the air and stamps his feet and begins to dash through the carpeted streets in an ecstatic rampage. He runs and yelps and cavorts, shaking his fists at the sky in a blizzard of joy, a madcap snow dance before the gods of the upper air.

Shealagh and I chase after our son, sprinting to catch up with this dervish, who’s whooping and hollering as if there is no tomorrow….

He keeps dashing through the streets with giddy, outstretched arms, pounding the snowy asphalt with his little legs and reaching for the fertile sky, as if he could grasp and salute all nature’s glory in one great, grinning embrace.

He’s the happiest little boy in the world, and his face is filled with wonder at the unfolding and eternal splendor of life.

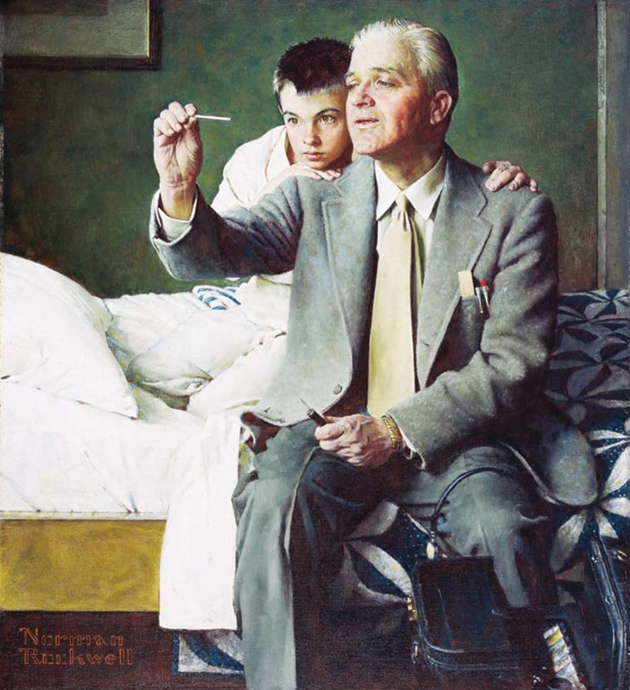

This is followed by a photograph of an older Damon, a handsome boy with a rich mop of hair and a full toothed grin.

And so we understand the truth of that young pediatrician’s words. It is an honor to know these children

-

1

See Jerome Groopman, The Anatomy of Hope: How People Prevail in the Face of Illness (Random House, 2004). ↩

-

2

See Jerome Groopman, How Doctors Think (Houghton Mifflin, 2007). See also Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011) as well as Freeman Dyson’s review in these pages, December 22, 2011, and Daniel Kahneman’s reply in the January 12, 2012 issue. ↩