Cindy Sherman has explored different kinds of photography, but she has become one of the most lauded artists of her generation for her photographs of her impersonations. Since she arrived on the scene, in a 1980 exhibition, when she was in her mid-twenties, she has come before her own camera in the guise of hundreds of characters, and as an impersonator—which in her case means being a creator of people, and sometimes people-like creatures, who we encounter only in a single photograph—she has been remarkably inventive. Especially as a portrayer of types of people, whether someone who appears to be a perky suburbanite in town for a matinee, or a woman in a sweatshirt who seems both tired and bristling, or a club singer belting out a note, Sherman—who is now, at fifty-eight, the subject of a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—has shown herself as well to be a witty and shrewd social observer. And the sheer human spectacle of someone continually transforming herself into one person after another has proved riveting.

But the playacting nature of Sherman’s photographs may account for why I, speaking perhaps for a small minority in the art world, have over the years found her art emotionally detached, even a bit bland. The work of a very particular talent, her pictures have seemed off in a province of their own. Hardly less important is that Sherman’s photographs, taken as objects in themselves, have felt merely serviceable. Generally in color and three or four, even eight, feet on a side, her shots lacked some distinctive formal altering of the medium. Diane Arbus, say, made the square-format photograph, where the center of the image often seems to push out at us, somehow synonymous with an apprehensive yet confrontational view of existence. Sherman the photographer, though, seemed chiefly at the beck and call of Sherman the mime.

There have been, of course, elements in her pictures that are personal to her. Her various accessories and props are appealingly economical and rudimentary, and, given that her art is based on deception, one could say that her large photographs, which sometimes come with transparently cheesy frames, are meant to have the appearance of fake paintings. During much of the 1990s, she also experimented, in pictures she herself was not in, with close cropping and artificial, theatrical color and lighting. But none of this quite erased the way that her pictures in general, and certainly those in which she appears front and center in some disguise, often had the disembodied presence of blown-up shots from one kind of movie or another.

At the Modern’s large show, however, I found that in some of her recent work, where she situates her characters in settings such as rooms or courtyards—settings that have a life of their own—her pictures have a welcome spatial tension. And her exhibition is undeniably absorbing and entertaining. It suggests that Sherman has an edgily comic and, as a painter friend of mine termed it, almost misanthropic view of life, and this gives her art an unexpected impact. Not that her temperament comes across in any programmatic or consistent way.

Sherman appears to be a highly intuitive artist. Over the years, as various recondite poststructuralist and feminist theories have been advanced to describe her pictures, she hasn’t said much about such notions one way or another. She operates without any stated overall plan. She seems to go from one self-contained unit of work to the next in a let’s-try-this way, and, especially when her art is seen in a retrospective, it is stimulating, and fun, to see how it all connects (or doesn’t connect).

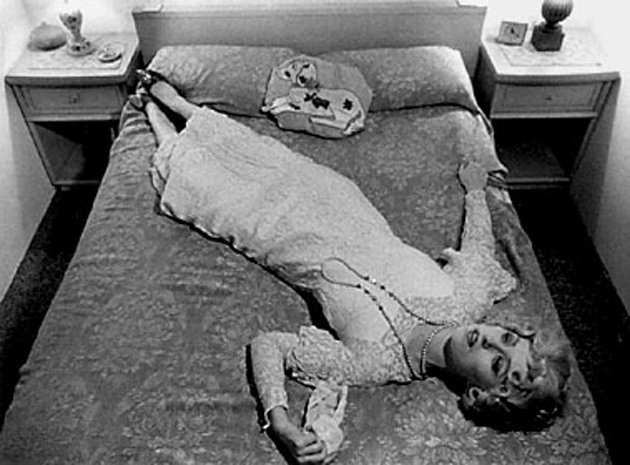

Sherman first became known for little black-and-white photos, called Untitled Film Stills, in which she impersonated the stock heroines, and stock female pawns, of movies from, it appeared, the 1950s and 1960s. Since then she has made many versions of this contemporary (or roughly contemporary) woman. In pictures that are always labeled Untitled, followed by a gallery inventory number, we see Sherman characters who, with appropriate clothing, wigs, and makeup, are worried, haughty, a bit battered (after a fight?), or wistful. Others might be wary, enraged, or fatuously oblivious of their effect on others (or so her crooners seem). But then, in the 1980s, she appeared in unsettling fairy-tale scenes, where she might be a sweaty, furtive creature with a snout, or, in a particularly vivid and memorable work from 1985, a wild child who reflectively holds her fantastically huge tongue in her hand.

In the late 1980s, Sherman made send-ups of old master paintings in which, whether intentionally or not, she appeared as somewhat embalmed-looking women and men. They are sitters who lack animating sparks in their eyes; and these pictures rarely do more than display a sophomoric kind of ribbing. (Although a few are versions of actual canvases—by Ingres, Raphael, and so forth—the majority, like all of Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills and her fairy-tale pictures, are her own inventions.) In her most disturbing work, which dates from the later 1980s and the 1990s, she is present merely in passing, or not there at all, in photos that, utilizing prostheses, masks, dolls, and substances resembling, among others, blood and vomit, show a world gone berserk.

Advertisement

The Modern’s exhibition seriously downplays this aspect of her art, but its flavor is quite present in a 1987 picture where buttocks, dotted with sores or boils, are thrust at us, or in a 1989 photo where we look at a mess of repellantly glistening, chocolaty goo from inside of which a fiercely animalistic face seems ready to spring forth. In a nightmarish 1992 work, the slightly grinning mask of a crone sits atop a body of ill-fitting prosthetic parts, its legless lower half spread open to reveal a prominent vagina with a sausage stuck in it. When Sherman appeared, in a 2004 series, as so many leering, all-too-minatory clowns, she might have been showing the animating spirits behind what are known as her “disaster pictures” and “sex pictures.”

She has also been an outright, and pitiless, social commentator. She exhibited photographs in 2000 that, parodying the publicity stills actors send out, give us women who, as one reads in the Modern’s catalog, have been thought of as hopeless strivers. One alarmingly suntanned character, whose teeth seem bleached, oozes bonhomie, while another, wearing overly large glasses, has what one recognizes as a professionally mirthful smile. Even stronger are photographs from 2008 of women who, from their forbidding demeanors and the moneyed places they look out from (and from their steel-hard hair), might be socialites or patronesses of the arts.

It is in these grandly sized pictures—and in similar ones from the same time in which, through digital manipulation, Sherman manages to appear two or more times in one work—that she has consistently turned her backgrounds into key factors in her images. That the slightly dimmed, apparition-like settings are not the homes of these subjects but—as one reads in the catalog or can guess on one’s own—inserted shots of the Cloisters, Central Park, or other places is a nice cavalier touch. The not-quite-right backgrounds (which she experimented with, also successfully, in the early 1980s) make the pictures feel, to their advantage, like collages.

The end result of Sherman’s many approaches is a roller coaster of discontent, at times recalling Otto Dix, at other moments Carol Burnett. Sherman can be reproachful and quietly barbed, or merely leaden and gloomy, or showily horrifying, or buoyantly nasty. The works that held me longest were of her strivers and her patronesses. They bring together the poles of Sherman’s thinking: her feeling for contemporary life and for the monstrous. We see people who, carefully but excessively made up, have turned their faces into masks. This can be said of her clowns as well, but they are so fully masked that we have little sense (as we have little sense with actual, professional clowns) of the person underneath the makeup.

More crucially, clowns, whether threatening or sad, are so familiar a theme that it is hard to put much stock in Sherman’s versions, which add little to the lore. With her overly avid women and her lionesses of the social scene, however, we feel we look, in each picture, at three people. There is Sherman herself, who, with her fair hair, pale eyebrows, and somewhat pointed features, resembles women in Memling portraits. Then there is her subject, who is clearly hidden behind a protective armor.

Sherman has made few other works, I think, where we are given so much pleasurable, and occasionally stumping, detective work as we try to figure out how she has gone from the face we know is hers to the faces she has invented. Her pictures of these ogres lampoon known types and perhaps easy targets. But this gives a welcome tension to Sherman’s art. We essentially know who she is satirizing, and so we have a way to measure how fully she has entered into the spirit of her subjects. With many of her other pictures over the years, whether of a perhaps saddened young woman who waits by a phone, or of a man or a woman from an earlier century in a takeoff of museum art, she transforms herself into no one in particular.

Advertisement

But then Sherman’s work is engaging no matter what we think of it as art. It isn’t surprising that for decades now she has regularly had significant shows in many parts of the world. The Modern’s exhibition, to give a sense of her fame, is her third major American retrospective since 1987, and its catalog is appearing simultaneously in English, Spanish, French, and German. Her work holds us in part because it is hard to pin down what exactly it is. Her photographs can be taken as records of someone who we don’t know whether to call a performance artist or an actress. For some writers, Sherman’s individual picture is apparently like a whole movie contained in a single scene. In that her working process is undoubtedly a matter of her seeing how a hairdo, clothes, and makeup cohere with a facial expression and a bodily stance, Sherman appears to think as much like a novelist as a visual artist.

On the most literal level, though, we look at someone who has a gift for impersonation. Born in New Jersey and raised on Long Island, Sherman went to Buffalo State College in the early 1970s with the idea of becoming a painter. But she had been disguising herself as different people since childhood. There is a photo of her in the Modern’s catalog around age twelve in which, standing on a suburban street along with a friend who is also in masquerade, she appears convincingly as a little old lady. In college she was exposed to conceptual art, which, already supplanting painting as the field that art students wanted to work in, enabled her to see that she could build on her feeling for impersonation.

The art that she made out of this feeling is, on some level, primitively direct in its appeal. Her pictures are probably alive for children in the same way they are for adults. Her photos remind us of thoughts that can gnaw on us when we are young and that perhaps never fully go away—thoughts such as “How much of my identity is really about my appearance?” or “What would it be like to be someone else?” or, more plaintively, “Can I become someone else?” It makes sense that Sherman fashioned a series of fairy-tale scenes, because in a way her entire endeavor is like a story for children. (It brought back to me Ozma of Oz, in which a character Dorothy meets, Princess Langwidere, has a new face for every day of the month, and keeps them at the ready, each in its own cabinet—rather like a Cindy Sherman show—in a special room.)

Sherman isn’t the first artist to come before the camera in a series of disguises or impersonations. Surely no artist, though, has used the notion as a premise for an entire career, and it creates for her audience a rare sense of intimacy with her and suspense about where she will go next. We seem to look at someone who has indentured her very person for the sake of her art. We can believe we are in this strange lifelong adventure with her, and, especially if we are her age or older, we wonder a little apprehensively how she will handle the issue of aging.

She has had the freedom all along to portray old people. One of her takeoffs of the old masters where real emotion breaks through is, it would seem, about the vulnerabilities of advancing years. It is a touching and harrowing picture in which we see a seated, vaguely distraught elderly person, perhaps from the time of the French Revolution, who is undressed from the waist up and has heavy, pendulous (prosthetic) breasts. When Sherman becomes old herself, however, she will be far less able to turn around and become a young person. Although she can alter her features digitally, as she has been doing recently in subtle ways, her options overall surely will narrow.

Because Sherman is in most of her photographs, and there is almost never anyone else in them, her art seems as well to have an unusual overall unity. This can be felt even though—or maybe because—she has moved over the years from one fairly self-contained series of work to another. We almost automatically assume that she is telling one long autobiographical story. Of course, most artists mature, or coast (or collapse), in full public view. But she gives the process an immediacy.

By the same token, Sherman has long been thought of, both by her admirers and by more skeptical viewers such as myself, as somehow separate from her contemporaries. But at the show I was struck by how much she shares with a number of them. When she first became known, the term Neo-Expressionism was heard a good deal. It was used, sometimes in a mocking way, to describe many of the new artists of the moment. Mostly painters and mostly men, they were seen as turning the clock back to a range of values and ideas whose time, many thought, was past. They made not only representational pictures but heroically large ones—canvases that, in Eric Fischl’s case, captured violent undercurrents of American suburban life, or, in David Salle’s art, braided together private moments with the seemingly random associations of one person’s flow of consciousness.

At the same moment, other emerging artists, many of them women—they included, besides Sherman, Barbara Kruger and Laurie Simmons—were viewed as an antidote to the painters. They seemed to be going in a more measured, analytical, and ironic direction. They made photographs but their concern was less photography as a fine art than awarenesses in the culture, particularly social attitudes that kept appearing in the media, that could be documented by or reenacted before the camera. Sherman’s early Untitled Film Stills, which for some viewers represented an almost objective report on the roles that women felt they had to play in a male-dominated world, were prime examples of this attitude toward photography.

At Sherman’s retrospective, though, one wonders if any of the so-called Neo-Expressionists—their number also includes Carroll Dunham, the late Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Julian Schnabel—have been as consistently expressionistic in their work as she has. It is hard, in fact, to see how she is so different from them (or from certain other figures of the time, such as the late Mike Kelley, who were not primarily painters). She has been employing ever-larger formats; and she shares with many of the artists a profound rapport with movies, surely the most vital art form during the years when all of them were coming into their own. (Like Salle and Simmons, Sherman has directed a film, the 1997 Office Killer, with Molly Ringwald and Carol Kane, and Schnabel has directed a number of them.) And while her scenes of sexual violence are macabre to a degree that sets Sherman apart, it is worth noting that sexual imagery—even sexual imagery that like hers shades into a world of ghoulish doings—pervades the pictures of these artists.

Along with many of them, Sherman gives us an expressionism—to use this sweepingly large term for the moment—that is not easy to define. It is not, as were earlier kinds of expressionism, about embitterment, or the specter of death, or a quest to connect with the unconscious. Coming from artists who grew up, in the late 1950s and 1960s, in a time of great national wealth and self-assurance, it can present contemporary life as, rather, overbearing, even frightening, yet in down-to-earth and occasionally funny ways. My opinion is undoubtedly suspect, as I have been a rather distant admirer, but I believe that, especially in her work in these later years, Sherman does full justice to this complex note.