1.

Lives of architects written by their sons are a tradition at least as old as Parentalia (1750), an account by the namesake child of Christopher Wren. Closer to our own day is John Lloyd Wright’s My Father Who Is on Earth (1946), whose subject—the all-controlling but parentally vagrant Frank Lloyd Wright, who abandoned his long-suffering first wife and their six offspring to elope with a client’s spouse—tried to quash that memoir. “Of all that I don’t need and dread is more exploitation,” the architect wrote to the author. “Can’t you drop it?”

Most recently, we have had Nathaniel Kahn’s Oscar-nominated movie My Architect: A Son’s Journey (2003), which concerns his emotional ties to his brilliant absentee father, Louis Kahn, who sired three children by three women (one of them his wife, another of them Nathaniel’s mother). James Venturi, the only child of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, is at work on a long-awaited film about his parents, Learning from Bob and Denise; while Tomas Koolhaas is preparing a documentary on his father, titled Rem.

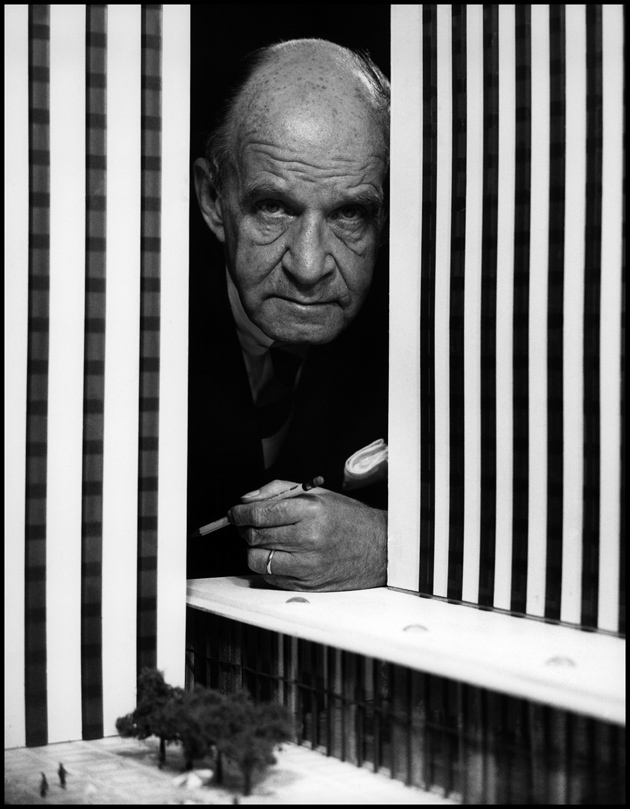

Hicks Stone, a son of Edward Durell Stone—who was lionized during the 1950s and 1960s, died in 1978 at the age of seventy-six, but today is almost unknown to a younger generation—is the latest child of a prominent architect to commemorate his father in print. Memoirs by scions of celebrities are instantly suspect of being either hagiographies or hatchet jobs. Yet Edward Durell Stone: A Son’s Untold Story of a Legendary Architect provides a judiciously balanced and often unsparing assessment of the author’s parents: the affable alcoholic designer and his ambitious second wife (the writer’s mother), an Italian-American bombshell aptly called Maria Elena Torch—a shameless publicity-seeker who persuaded her once-lackadaisical husband to go on the wagon, use his full name, and become a global celebrity.

The disparity between Stone’s fame during his lifetime and his veritable disappearance from the canon after his death is as if the general public in 2050 were to have no idea who Renzo Piano was. (In fact, the Italian architect’s shoebox-shaped, colonnaded structures bear more than a passing resemblance to Stone’s, as seen in Piano’s California Academy of Sciences of 2000–2008 in San Francisco.) This posthumous reversal of fortune seems even stranger given the extraordinary range of Stone’s numerous, far-flung, and prestigious commissions.

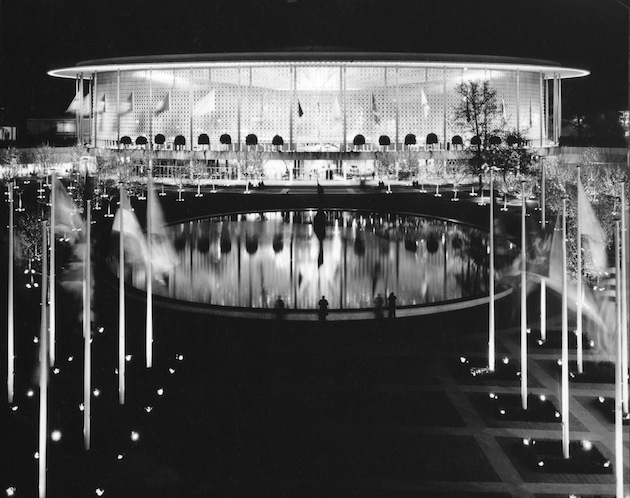

His jobs included state capitol buildings in North Carolina and Florida; the American embassy in New Delhi; skyscrapers for Standard Oil in Chicago, General Motors in New York, and the International Trade Mart in New Orleans; houses for Vincent Astor in Bermuda, Clare Boothe and Henry Luce in South Carolina, and Victor Borge in Connecticut; campuses for Harvey Mudd College in California, Windham College in Vermont, and the State University of New York at Albany; the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico, the Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer in Nebraska, and the Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art in New York City; the Stanford University Medical Center and the Eisenhower Medical Center, both in California; corporate headquarters for Tupperware in Florida, Pepsico in Westchester County, and the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C.; the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, also in the nation’s capital; and the structure that rocketed Stone to international renown, the circular US Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, which set off a brief worldwide vogue for that uncommon building shape. Whether or not one likes Stone’s work, there is no denying that he was one of the most representative architects of America at the height of its postwar prosperity and power.

2.

Edward Durell Stone was born in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in 1902 (a year after Louis Kahn and four years before Philip Johnson, respectively the most gifted and the most celebrated American architects of their generation). Although his father was a successful dry-goods merchant and his hometown is the seat of the state university, Stone always considered himself a country bumpkin, a lingering insecurity reflected in his choice of socially adept wives and appetite for lavish living.

Although he never took a degree in architecture, his apprenticeship in a Boston architectural firm was an educational alternative no different at the time from an aspiring attorney’s clerking in a legal office instead of going to law school. Stone’s impressive drafting skills were recognized when in 1927 he won the Boston Architectural Club’s coveted Rotch Traveling Fellowship, a two-year stipend for a European Grand Tour that included a sojourn at the American Academy in Rome.

From his study of Beaux-Arts drawing techniques and of Classical monuments, Stone absorbed Beaux-Arts architectural values that he retained throughout his career, as was also true of his great contemporary Kahn, an even more talented draftsman. Though he easily picked up the new aesthetic of modernism during the following decade, he never lost respect for the cardinal Beaux-Arts principles of symmetry, a strongly defined central circulation route (the marche), and the tripartite handling of exteriors in the Classical division of base, column, and capital.

Advertisement

After working as an assistant on Schulze & Weaver’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel of 1929–1931 in New York City (where he designed the still-intact ballroom), Stone got his big break in 1931 when he was hired by Associated Architects, the huge architectural consortium assembled to execute Rockefeller Center. That mixed-use office, retail, and entertainment complex in midtown Manhattan was America’s biggest urban development scheme during the Great Depression, when one quarter of the country’s architects remained unemployed. Stone’s contributions to Radio City Music Hall of 1931–1932 included the theater’s monumental proscenium of four concentric golden arcs, as well as the soaring Grand Foyer, one of New York’s most uplifting indoor public spaces, an unrivaled populist masterpiece.

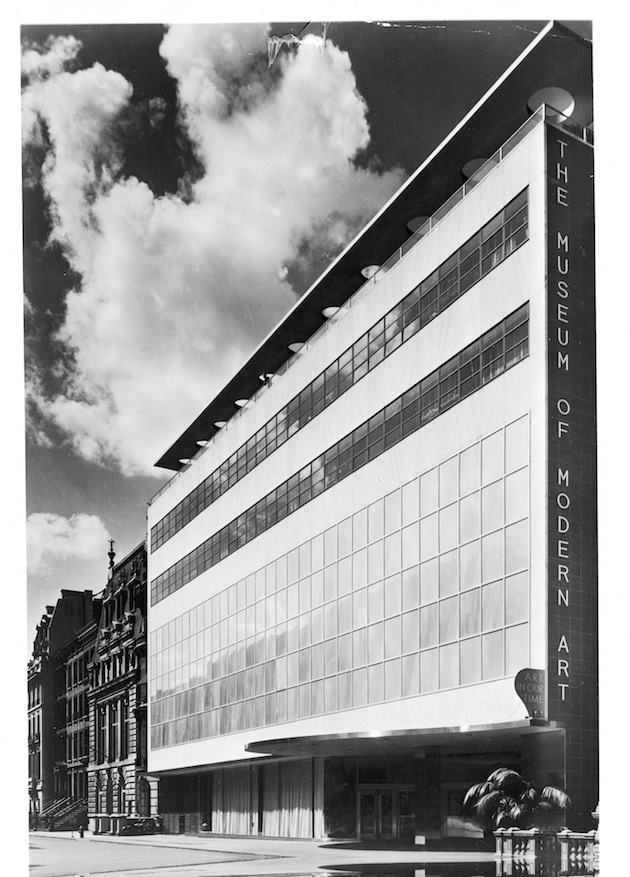

Associated Architects was overseen by Wallace K. Harrison, a Rockefeller family in-law and the dynasty’s architectural majordomo for half a century. He recommended Stone as codesigner for another Rockefeller-sponsored project, the recently established Museum of Modern Art’s first purpose-built home several blocks north of Rockefeller Center. Although MoMA’s founding director, Alfred F. Barr Jr., composed an excellent shortlist—Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, J.J.P. Oud, and Frank Lloyd Wright—his recommendations were set aside by the museum’s board, which handed that plum assignment to their fellow trustee Philip L. Goodwin, a routinier Beaux-Arts architect whose main qualification, as the museum’s first architecture curator, Philip Johnson, candidly recalled, was “money, money, money.” Stone was given the unenviable task of steering the design away from Goodwin’s conservative proclivities and toward the Modernist aesthetic the young institution was promoting. It is to Stone’s credit that the mismatched partners’ Museum of Modern Art of 1936–1939 emerged as a thoroughly respectable if not quite thrilling specimen of the International Style.

3.

During World War II, Stone served as a major in the US Army, and while stationed in Washington, D.C., he designed airfields and military bases. When peace came the architect applied his newly acquired organizational abilities to large-scale projects that included resort hotels in Panama and Lebanon, as well as colleges across the United States as higher education boomed. His workload grew to an enviable degree, and he found a paradoxical admirer in Wright, whose revolutionary reputation stemmed from breaking out of precisely the kind of static boxlike configurations that Stone resorted to time and again during his postwar period, as opposed to the often dynamic layouts of his prewar houses.

Wright blamed his brush with oblivion in the 1920s on the strict reductivism espoused by Corbusier, Gropius, Mies, Oud, and other European modernists who abjured all applied ornament and pattern. After his triumphant comeback in the 1930s, Wright embraced increasingly florid decoration to set his work apart from that of his nemeses who championed the pared-down International Style. This is where America’s greatest architect and the profession’s latest sensation found common ground.

In Stone’s Stanford and Harvey Mudd ensembles he paid Wright the compliment of using geometrically patterned pre-cast concrete components clearly derived from the old master’s Pre-Columbian-inspired “textile block” concrete construction system of 1922–1923. Wright in turn said he admired Stone’s widely praised US Embassy of 1954–1958 in New Delhi, and went so far as to claim it was more beautiful than the Taj Mahal, proof that he had never laid eyes on either.

Wright’s ferocious third wife, Olgivanna, always with an eye on the main chance, encouraged a friendship between the two architects as Stone’s star began to rise. The Montenegrin-born Olgivanna, an acolyte of the spiritualist G.I. Gurdjieff, thrived on intrigue and loved to meddle in the sex lives of the Taliesin Fellowship, Wright’s architecture school–cum–professional office. After his death in 1959 there was a sharp drop-off in commissions, and the widow Wright hatched a byzantine plot to draw the Stones deeper into the Taliesin circle in order to profit from his connections.

As Hicks Stone writes of his mother and her new best friend, “They confided in each other about the details of their marriages, the sexual behavior of their husbands, and the role a wife can play in her husband’s architectural practice.” Convinced that if Ed Stone were made jealous enough he’d spend more time at Taliesin West in Arizona, the sinister Mrs. Wright successfully masterminded an affair between Maria and a neurosurgeon she had tutored in Gurdjieff’s beliefs. But that dalliance wrecked the Stones’ already stormy marriage, and the wicked old schemer, who belatedly feared a scandal, banished the hapless adulterers from her desert court.

Advertisement

4.

Much as Francis Bacon bitchily referred to his macho fellow painter Jackson Pollock—known for his airy, looping skeins of pigment—as “the lacemaker,” that sobriquet also could have been applied to Stone once he began wrapping decorative white filigreed screens around his buildings in the early 1950s. Johnson, a much better critic than designer, delivered the sharpest one-sentence verdict on Stone when he observed that “architecture is more than putting drapes in front of a house to hide it.”

One of the more egregious applications of that idea was the lacy white façade Stone tacked onto his own Victorian townhouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, which sticks out from its row of stolid brownstones like an enormous antimacassar. Easily and cheaply mimicked in precast concrete and other composite materials, knockoffs of his pierced screens quickly became ubiquitous architectural clichés throughout the Sun Belt, where countless breezeways and carports bear silent witness to the false dawn of a new Stone Age.

Even fellow architects who saw good qualities beneath the froufrou surface of Stone’s postwar work were exasperated by his constant reiteration of patterned screens. Eero Saarinen, his principal rival for high-profile corporate commissions and another darling of the mainstream press in the 1950s (both appeared on the cover of Time magazine, a big deal back then), averred that “the best thing that could happen to Ed Stone would be for someone to take his grilles away from him.”

By the 1960s that opinion became so widespread among Stone’s critics and potential clients that his office managers curtailed and eventually banned his hallmark motif, more as a marketing strategy than as an artistic principle. Alas, what lay behind the grilles was not particularly interesting, and without those seductive peekaboo veils it became all too obvious that the exposed volumes of his unadorned work lacked both the raw power of Brutalism and the understated rigor of Minimalism, the two dominant architectural trends of the 1960s and 1970s. Stone’s simpler late-career structures, almost always clad in white masonry deployed in vertical stripes, exude the denuded and forlorn air of freshly shorn sheep.

Vincent Scully, the influential architectural historian who made the critical reputations of both Kahn and Venturi, was exceptional during the postwar period for being wholly receptive to new expressions of the Classical tradition, as exemplified by Kahn’s majestic Roman-inspired forms and the playful Mannerist and vernacular conceits of Venturi and Scott Brown. But Scully could not stomach what he saw as the debased values of Stone and his closest contemporary counterpart, the Japanese-American architect Minoru Yamasaki (whose best-known work, the twin-towered World Trade Center of 1966–1977 in New York City, conformed closely to Stone’s white-clad, vertical-striped high-rise format). As Scully wrote in 1969 of that shared aesthetic:

It is superficial classicism; and it is, literally, superficial design, where the volume, into which the functions are more or less fitted, is fundamentally Miesian, symmetrical, and not overly studied, but the surface is as crumpled and laced up as the trade can afford.

Stone’s rigid tendencies were most apparent, and deleterious, in his comprehensive planning schemes, never more so than in his Uptown Campus of 1954–1958 for the State University of New York at Albany. Its obsessively symmetrical layout—centered by a vast colonnaded oblong of interconnected mirror-image pavilions and roofless courtyards—is bounded beyond its outer corners by four identical freestanding high-rises surrounded at the base by deep arcades.

The quadrangle has been a defining element of collegiate design since the Middle Ages, when such inward-facing spaces grew incrementally and organically out of monastic prototypes and reflected the functional relationships of the buildings that surrounded them. In contrast to the logical evolution and essential intimacy of medieval university ensembles, the superscale, unitary nature of Stone’s Albany campus is decidedly arbitrary, not to say Procrustean. For example, the handling of the four principal atriums is so similar that it is hard (at least for the occasional visitor) to tell exactly where within the complex one is. Likewise the indistinguishable appearance of the identical outlying towers makes it difficult to read those vertical elements as accurate reference points.

Another deficiency of this scheme—and of Stone’s oeuvre in general—is a blithe disregard for climatic conditions, as seen at Albany in his fetishistic fondness for open plazas and porous peripheries, particularly unsuitable for that city’s frigid winters. But in that respect Stone was no different from his old boss Harrison, whose brutally exposed and windswept Empire State Plaza of 1959–1976, also in Albany, would likewise be more appropriate in Brasília than the northern Hudson River Valley. Although Stone’s perforated outer walls may have made good environmental sense in tropical settings—particularly the New Delhi embassy, where his openwork panels updated the traditional jali that shaded and ventilated classical Mughal architecture—he applied that idea so indiscriminately everywhere in the world that rather than seeming an outgrowth of well-considered design it became a mere styling gimmick.

5.

Changing attitudes toward Stone’s work were evident by the turn of the millennium, when one of the most misjudged preservation battles in recent decades attracted a disproportionate amount of attention given the historical insignificance of the building involved: his Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art of 1964–1965 in New York City. Commissioned by and named for the eccentric A&P supermarket heir, this privately endowed institution was conceived as a contrarian riposte to the Museum of Modern Art and what Hartford—whose taste in painting ran to the then deeply unfashionable Pre-Raphaelites and the later work of Salvador Dalí—saw as the overly restrictive view of modernism advanced by MoMA. It was therefore no coincidence that he turned to that museum’s architect for his rival gallery, although the results were strikingly different from Stone’s textbook exercise in International Style orthodoxy for MoMA three decades earlier.

The highly visible, easily accessible, but tightly restricted site that Hartford chose for his quixotic project occupied a small traffic island at the southern end of Manhattan’s chronically ill- defined Columbus Circle. He maximized the small rectangular ground plan by extending the structure to a height of ten stories, and created an illusion of greater depth at street level by pushing the building envelope out to its permissible maximum on all four sides and then encircling the base with an arcade of oddly stylized columns that Ada Louise Huxtable, writing in The New York Times, indelibly likened to giant lollipops. Above them, the building’s white marble facing was trimmed with eyelet-like holes around the edges, rather than the architect’s more typical all-over perforation pattern.

Stone, never very imaginative with spatial solutions, was unable to create any satisfying interiors within the structure’s constricted carapace, and the Hartford’s attenuated, awkwardly proportioned display rooms felt oppressively claustrophobic. The enterprise was a financial bust for the profligate patron, and after he closed the gallery in 1969 the building was taken over by the city and used as offices for its Department of Cultural Affairs.

A leading voice in favor of the old Hartford’s preservation was The New York Times’s erratic and self-dramatizing architecture critic, the late Herbert Muschamp, who in 2006 wrote a rambling 5,600-word polemic, “The Secret History of 2 Columbus Circle,” which urged that the endangered structure be saved not as a meritorious landmark of design, but rather as an important locus of metropolitan gay culture. That retroactive designation came as news to many homosexual museumgoers old enough to remember the gallery in its prime, as it would doubtless have to the building’s rampantly heterosexual begetters, Hartford and Stone.

However, unless one necessarily synonymizes camp with a gay sensibility, it is hard to buy Muschamp’s proposition, which seemed very much a matter of personal projection, a characteristic of his criticism as a whole. In any event, the Hartford’s vague resemblance to a Venetian palazzo as it might have been reimagined by RKO’s art director Van Nest Polglase for the Fred Astaire–Ginger Rogers musical Top Hat (1935) puts this urban curiosity more firmly in the realm of kitsch rather than camp.

In the end, the former Hartford was stripped down to its steel skeleton and reconfigured by Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture as the new home of the Museum of Arts and Design (formerly called the American Craft Museum), which opened in 2008. As silly as the original building may have been, it was certainly preferable to the deadening makeover it received from Cloepfil, who reclad the exterior in white and gray tiles that impart all the charm of a subway pissoir. Only in comparative terms can the effacement of Stone’s fanciful exterior be seen as a loss, and regrets for its passing as anything more than misdirected sentimentality.

Thus despite Hicks Stone’s valiant efforts to secure a higher place for his father in architectural history, he still seems a middling product of his times, though personally more interesting than one had imagined. As this thorough new life-and-works indicates, he was an opportunistic artist on a par with the painter Adolph Gottlieb, a year-younger contemporary who likewise hit upon a readily marketable formula and then cranked out increasingly weaker variants of it until the work devolved into sad self-parody. But now, at a time when melodramatic midcentury period pieces such as Todd Haynes’s Far from Heaven (2002), Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men (2007–), Sam Mendes’s Revolutionary Road (2008), and Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) captivate audiences with their wistful backward glances toward an ascendant (if hardly untroubled) America, we should not discount the nostalgic spell that Edward Durell Stone’s peculiar brand of modern romanticism can still exert on suggestible postmillennial escapists.