A reader climbing the great staircase of the British Library’s modern premises near St. Pancras Station in London is confronted suddenly by that wonderful building’s most wonderful feature. Behind the glass walls of an internal tower six stories high, more than 60,000 sumptuously bound books stretch upward, shelf upon shelf, a cliff-face of leather and gilt lettering gleaming softly through the tinted glass. In that architectural coup de théâtre, a world of learning serves as the visible core of a building created to contain all the learning of the world.

In its day that display, the so-called King’s Collection, made up one of the greatest of Enlightenment libraries, assembled over a lifetime of dedicated book-buying by the bookish King George III. It rests now at St. Pancras because within ten years of the old king’s death in 1820, his books were presented to the nation by his son, King George IV. “Prinny,” as his subjects liked to call him (half affectionately, half contemptuously), was a lavish patron of the visual arts, but not much of a reader. More to the point, perhaps, he was eager to clear the site of the run-down royal residence at the western end of the London Mall where his father’s library was stored, in order to build Buckingham Palace, a lavish setting for his own overblown notions of royal grandeur.

George III had created a great library for himself in part because the monarchy he inherited in 1760 from his grandfather had disposed of all its books just three years earlier. The Old Royal Library had been a magnificent collection of more than two thousand medieval manuscripts and nine thousand printed books. Begun in the 1470s by King Edward IV, though incorporating many older books, it had been expanded over the centuries, not least by an influx of loot from the monastic libraries dissolved during the English Reformation. But the entire collection was signed away to the nation in 1757 by King George II.

His motives are far from clear, but he almost certainly felt no pang at the parting, for he cared nothing about books. “Rex illiteratus est quasi asinus coronatus,” declared the twelfth-century scholar John of Salisbury: “A king without learning is like a donkey with a crown.” If so, George II was to father a long line of donkeys, for, his grandson George III apart, the monarchs of the House of Hanover were more noted for their devotion to horses and the hunting field than to the pursuit or patronage of libraries. Alan Bennett playfully exploited the persisting reputation of royal philistinism in the House of Windsor in his 2007 comic novella The Uncommon Reader. In it, Queen Elizabeth II happens upon a van containing a circulating library, intended for the use of the palace servants, and discovers in herself a compulsive love of reading. There follows a sharp decline in her attention to duty, with disturbing consequences for the constitutional position of the Crown.

Bennett’s fable depended for its humor on the wild improbability of a bookish monarch. But it was not ever thus. For earlier English royal dynasties, as for their European counterparts back into late antiquity, the creation of lavish royal libraries had been one of the pillars of royal reputation and display. The Yorkist King Edward IV, the Tudor Henry VIII, and the Stuart Charles II, as well as the Merry Monarch’s uncle, the young Prince Henry Frederick, who had died while heir apparent to James I in 1612, were all avid book collectors. Between them they assembled the superb collection that George II parted with so lightly in 1757.

Allowing for items mislaid or misappropriated during the many mishaps and migrations of the collection before and after 1757, that collection, the Old Royal Library, remains one of the glories of Britain’s national book collection. Unlike George III’s books, however, on spectacular permanent display in their new tower of glass, no one for centuries has seen the Old Royal Library assembled in a single place. Its two thousand manuscripts have been absorbed into the library’s general holdings, and lie hidden from view in the air-conditioned obscurity of the stacks.

The “Genius of Illumination” exhibition recently put on show 111 of the Old Royal Library’s 1,200 illuminated books, together with thirty-seven complementary manuscripts with royal associations, drawn from other collections. All are illustrated in the exemplary catalog, which also provides three fascinating essays by the editors tracing the history of the royal libraries. Though fewer than a tenth of the royal collection’s illuminated books were included, the show offered a concentration of pictorial glory surviving with an intensity and opulence that exists in almost no other medium. Most medieval art objects—wall paintings, panel paintings, jewelry, or carved statuary—have fallen casualty to time in one way or another. The majority have been lost, and what remains is often dilapidated, faded, incomplete. Medieval paintings and statues were mostly religious, and myriads of images were therefore scraped or hammered or burned into oblivion by zealous Protestant iconoclasts in the sixteenth century. And most of the precious metalwork into which so much medieval craftsmanship and wealth were poured has long since been broken up and melted down for its bullion and gemstone value.

Advertisement

Most medieval manuscripts, too, have perished. But where they survive, they are often in better condition than any other kind of medieval artifact. The splendor of an illuminated manuscript constituted a form of conspicuous consumption valuable only for itself. A book, however costly, is a book: it cannot be melted down for bullion. Pages might be removed for the sake of the individual miniatures they contained, whole volumes might be ripped up or burned as the superstitious rags of popery, texts considered redundant might be carelessly dismembered to wrap cheese, or to do humbler duty still in the privy. In the course of the English Reformation, whole libraries were lost in this way.

But for all that, medieval books endure still in their thousands. The sheep- or calfskin on which they were written is remarkably durable, and a closed book protects bright colors from the bleaching light. So the British Library exhibition was, among other things, a heart-stopping display of some of the most perfect surviving medieval works of art, pictures and text created for monarchs, centuries old, yet as fresh as the day they were completed. Their bright pages, many included in the catalog under review, offered window upon window into the medieval world as it imagined itself, gloriously frozen in vermilion and lapis lazuli and burnished gold.

Not all these royal books, though, were displayed for the splendor of their pictures. The very first item in the exhibition was a worn and rather dowdy early eighth-century Latin gospel book, with few illuminations and no pictures, though it was probably written in the same scriptorium as the more famous and far more spectacular Lindisfarne Gospels, the illuminated Latin manuscript now in the British Museum. But the Old Royal Library gospel book is remarkable all the same, for it contains an added note in Anglo-Saxon, recording the manumission of a slave by King Athelstan, immediately on his accession in 925. This moving record of the king’s magnanimity (the earliest such manumission to survive) suggests that the book was being used for services in Athelstan’s own chapel royal at Winchester.

The Lindisfarne book is exceptional in the Old Royal Library because it is a liturgical book, designed for weekly use at Mass. It is not in itself surprising that altar and choir books, however sumptuous, rarely feature in the catalogs of aristocratic or royal libraries, for they were kept where they were needed, in the vestry or the chapel book chest. But in any case, the religious upheavals of the sixteenth century took their toll on these kinds of books in particular. In 1550, Edward VI’s Protestant government decreed the systematic destruction of every medieval liturgical book in England, and in 1551 the Privy Council specifically ordered “the purging of his Highnes Librarie at Westminster of all superstitiouse bookes.”

As a result, the Old Royal Library contains not a single missal, and only eight other liturgical manuscripts of any kind. It is equally thin in medieval books of personal devotion, with only eight books of hours and eighteen illuminated psalters, half of which entered the Royal Library only in the seventeenth century. These absences are truly remarkable, for psalters and books of hours are the most common of all medieval manuscripts, and every other comparable library contains multiple examples of them. The great eighteenth-century library of the Earls of Oxford, for example, whose manuscript collections are similar in scale and opulence to those of the Old Royal Library, and which is also in the British Library, has sixty-one psalters and 103 books of hours.

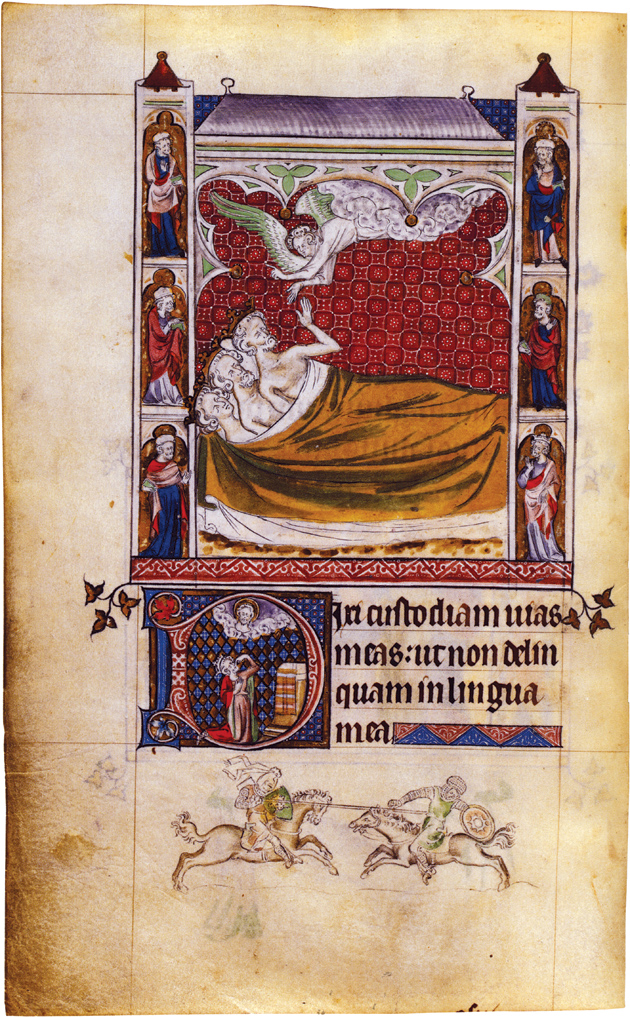

But the religious upheavals of mid-Tudor England brought gain as well as loss. Two of the psalters that do survive in the collection were presented to Queen Mary I, as part of the restoration of Catholicism after 1553. And one of those two, the so-called Queen Mary Psalter, has a fair claim to be one of the most beautiful books produced anywhere in the whole of the Middle Ages. The work of a single anonymous early-fourteenth-century English master, its 319 leaves contain no fewer than 223 prefatory tinted drawings, recapitulating the Old Testament from the creation of the world to the death of Solomon; twenty-four calendar pages with signs of the zodiac and labors of the months; 104 whole- or half-page miniatures; twenty-three historiated initials (i.e., enlarged and containing a figure or scene); and 464 marginal drawings.

Advertisement

No one knows for whom this sublime and lavish book was made, but in 1553 the manuscript, with its parade of delicate, curly-headed holy figures and its furred and feathered marginal bestiary, belonged to Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland. An ardent Protestant, Manners had made the huge mistake of supporting the Duke of Northumberland’s attempt to prevent Queen Mary’s accession, long after it was clear that this coup had failed. Imprisoned in the Fleet in July 1553, Manners’s goods were forfeit: his psalter, that miraculous and exquisite survivor of the Edwardine holocaust of “superstitious books,” entered the comparative safety of the royal collection.

As that suggests, English monarchs might acquire books by many means—by gift, by marriage, by spoil of war, and by confiscation. But some of them at least set out to buy them. In this they were self-consciously following the pattern set by fabled European royal book-collectors like Alfonso the Wise of Castile or Robert the Wise of Anjou, king of Naples. Looted and dispersed in the 1340s, much of Robert’s magnificent library found its way to the royal library of France, and from there a few of his books, including a lavishly illustrated history of Troy, even found their way to England: two of them were on display at the British Library.

But in the 1470s, Edward IV, who presided over what foreign visitors considered “the most splendid court in all Christendome,” determined to outdo all such royal predecessors and contemporaries by commissioning a series of deluxe manuscripts from the best workshops in the center of such production, the southern Netherlands. Edward seems especially to have favored sumptuously illustrated chronicles and world histories. These enormous (and enormously costly) books obviously mattered greatly to him. Despite their bulk, they may have accompanied him on his progresses from palace to palace, in specially constructed “cofyns of fyrre” (coffins of fir), though eventually they seem to have been settled in his favorite residence at Eltham, under the care of a yeoman employed specially “to kepe the kinges bookes.”

Edward IV almost certainly commissioned more new illuminated books than any other English monarch, and the fifty or so of his manuscripts remaining in the Old Royal Library form a distinctive and homogeneous group. The four hundred surviving manuscripts added to the Old Royal Library by Henry VIII represent fewer than half the 908 books we know him to have owned and kept in his “upper Library” at Whitehall alone, and Whitehall, though his main residence, was just one among the sixty royal residences Henry used.

We know in detail what books he kept at Whitehall, many of which have survived in the Old Royal Library, because a detailed Whitehall inventory not only lists all the manuscripts and printed books there, but even preserves their probable shelf order and physical arrangement. By contrast, the content of Henry’s libraries at Greenwich and at Hampton Court is entirely lost to us. The only inventory for the palace at Greenwich reveals that there were 329 books in “the highest library,” but says nothing about what they might have been, while the postmortem inventory for Hampton Court dismisses the large library there with the maddeningly imprecise “item, a greate nombre of bookes.”

Even so, Henry’s remaining books constitute 20 percent of the surviving Old Royal Library, making him by far the single most important royal contributor. Some of these books were specially commissioned, like the collections of motets copied and decorated in the Netherlands with Henry’s Tudor rose and the pomegranate of his queen Catherine of Aragon, or the magnificent Renaissance psalter illuminated by Jean Mallard for the king’s personal use, in which the bear-like figure so familiar from Holbein’s portraits appears both as the “blessed man” of Psalm I and as the royal psalmist, David, himself. But well over half Henry’s manuscripts were made for someone else, the majority confiscated from the monastic libraries he himself had dissolved, a staggering hundred of them from the single cathedral priory at Rochester alone.

These, however, were no random acquisitions: in the later 1530s, Henry’s book collecting was “issue-driven,” and he dispatched the antiquary and bookman John Leland to scour monastic and college libraries all over England for legal, historical, and theological texts that might provide backing for his divorce from Catherine of Aragon, and an intellectual pedigree for the novel doctrine of the Royal Supremacy. Relatively few of these working texts were lavishly illustrated, and it is one of history’s ironies that so high a proportion of the monastic libraries of England should have been preserved to help the man who had destroyed those libraries divorce his wife and renounce the pope.

Later royal bibliophiles, like Prince Henry Frederick and Charles II, built their libraries more serendipitously, by acquiring other people’s collections. Prince Henry, who modeled his collecting on European royal connoisseurs like the Emperor Rudolf II, was fortunate in acquiring (perhaps as a gift) one of the greatest of Elizabethan libraries, that of John, Lord Lumley. Lumley’s library in turn incorporated the books of his Catholic father-in-law Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel. Arundel had been a key figure in Mary Tudor’s regime, and in addition to many former monastic books, he had acquired about a hundred manuscripts from the library of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, executed by Mary’s Catholic regime in 1556. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of the surviving liturgical books in the Old Royal Library came from this Arundel-Lumley collection.

Charles II, the last great benefactor of the Old Royal Library, collected in a deliberate effort to replace the royal books lost in the depredations of the Civil War. Like his uncle Prince Henry, he benefited from the discriminating eye of another great collector, the Gloucester antiquary John Theyer, from whose estate he acquired, among much else, 334 manuscripts, the spoil of more than twenty West Country monastic houses. In 1678 Theyer’s manuscripts were valued at £841, a significant expenditure even for a Restoration king. Charles’s love of learning is, however, put in its proper setting by the fact that a few years before he bought Thayer’s books, he had given his mistress Nell Gwynn a present of £2,265, to buy silver ornaments for her bed!

Kings needed books for a host of reasons: to pray with, to play or sing with, to codify laws, or to map the realm’s coastline. Princes bought encyclopedias to master facts, they bought chivalric romances to while away long winter evenings, they bought illuminated Bibles to symbolize (and feed) their piety. An array of costly books in the king’s chamber proclaimed his wisdom, learning, civilization. Books on etiquette, morals, or the arts of war were needed to educate his heirs. These royal requirements did not change much over the course of the Middle Ages, and the books made to meet them often passed from hand to hand. The results could be poignant. One of the manuscripts from outside the Royal Library included in the exhibition was a lavish psalter illuminated in a London stationer’s shop for Prince Alphonso, son of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile, and heir apparent to the English throne. In 1284 the ten-year-old prince was betrothed to Margaret, daughter of the Count of Holland and Zeeland. The psalter, which was to be a wedding gift, was duly emblazoned with their arms.

But while work on the manuscript was still in progress, Alphonso died, the book lost its point, and the scribe put down his pen. Thirteen years later, however, Alphonso’s sister Elizabeth married John, Count of Holland, brother of Alphonso’s intended bride. Thriftily, and with the heraldry of the two royal houses once more apposite, the abandoned book was dusted down for completion in an East Anglian scriptorium. New calendars and illuminations were added, and the updated book assumed its interrupted role as the visible token of a royal alliance designed to straddle the North Sea. The manuscript remains, a monument to the fragility of even royal lives, and to the persistence of dynastic imperatives that transcended the mere individuals who served them.

A similar pathos surrounds several of the manuscripts associated with the tragic figure of Henry VI, who died in 1471. England’s claims to the throne of France in the age of Crécy and Agincourt brought many French manuscripts to England. John, Duke of Bedford, Henry IV’s third son, was an especially lavish patron, and the magnificent book of hours he and his Duchess Anne presented at Christmas 1430 to the young Henry VI was one of the glories of the exhibition, though it never formed part of the Old Royal Library. Several other books, intended to educate Henry in piety and kingcraft, were also on display: in one of them, another psalter given to him in his coronation year, the young king is portrayed being presented to the Virgin and her Son by Saint Louis, robed in Fleurs de Lys.

Henry’s court will have seen this jeweled image as a fitting affirmation of English claims to the throne of France. In fact, however, the portrait was painted before Henry was born, and originally represented Louis of Guyenne, dauphin of France, for whom the book was first intended, but who had died while still a minor in 1415. The transferred image, charged with doomed territorial aspirations, is all the more poignant because Henry VI was to prove ardently pious but hopelessly inept, and in his disastrous reign the legacy of Agincourt would be frittered away.

The marvelous exhibition at the British Library was composed of manuscripts, most of which have passed through many hands. At the risk of ending on a quibble, we should note that that very fact can make for ambiguity in describing a manuscript as “royal.” One of the most intriguing exhibits from outside the Old Royal Library was a parchment roll, eleven feet long and only five inches wide, decorated with prayers, rubrics, and religious emblems, such as the crucifix, the instruments of the Passion, or the wounds of Christ. Such rolls were intended for use in prayer, but also as a talisman, the mere possession of which could bring good luck, and which could be wrapped around the belly of a woman in labor for blessing and protection. Such rolls are rare—only sixteen are known to have survived—and this example is a recent arrival in the British Library, having been acquired from the library of a now defunct Roman Catholic seminary.

Its presence in the exhibition was due to the fact that, though commissioned in the late fifteenth century by an anonymous English bishop, who is portrayed on it in prayer, the roll was later customized by the addition of the badges of the future King Henry VIII, and the sheaf of arrows of his wife Catherine. Inserted between emblems of the Passion, the young Henry himself wrote a dedication to one of the gentlemen of the Privy Chamber, William Thomas: “I pray yow pray for me your lovyng master Prynce Henry.” The inscription is treated in the catalog as evidence that despite his future break with Rome, the young prince Henry practiced an entirely traditional Catholic piety: the distinguished Tudor historian David Starkey used this roll to make the same point in his recent biography of the young Henry.1

In fact, however, the badges may well indicate only that the roll belonged to someone in Henry’s household, and the inscription makes it clear that it was William Thomas, not Henry, who routinely prayed with it. Pious royal inscriptions of this kind were common in the prayer books of courtiers in early Tudor England2: an affectionate royal autograph in one’s book, produced in chapel, was a public token of royal favor. Henry may well have given William Thomas this secondhand (and by the early sixteenth century decidedly old-fashioned) prayer roll: there is nothing whatever to suggest that he himself ever prayed with it.