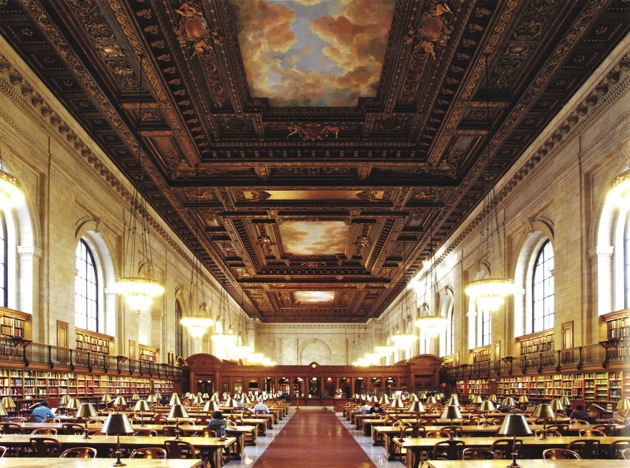

Anne Day

The Rose Main Reading Room at the 42nd Street branch of the New York Public Library; photograph by Anne Day from the new edition of Henry Hope Reed and Francis Morrone’s The New York Public Library: The Architecture and Decoration of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building. It is published by Norton.

Few buildings in America resonate in the collective imagination as powerfully as the New York Public Library at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. The marble palace behind the stone lions is seen by many as the soul of the city. For a century it provided limitless possibilities of gaining knowledge and satisfying curiosity for immigrants just off the boat, and it still opens access to worlds of culture for anyone who walks in from the street. Tamper with that building and you risk offending some powerful sensitivities.

Yet the trustees of the New York Public Library—I write as one of them but only in my capacity as a private individual—have decided to rearrange a great deal of that sacred space. According to a plan given preliminary approval by them last February, they will sell the run-down Mid-Manhattan branch library—just opposite the main public library on Fifth Avenue—and the Science, Industry, and Business Library (SIBL) at Madison Avenue and 34th Street, and they will use the proceeds to expand the interior of the 42nd Street building. They will not touch the famous façade on Fifth Avenue, but they will install a new circulating library on the lower floors to replace the Mid-Manhattan branch, whose collections will be incorporated into the holdings of the main library.

All this shifting about of books will require rebuilding parts of the infrastructure at 42nd Street. The steel stacks now hidden under the great Rose Main Reading Room on the third floor will be replaced by the new branch and business library on the lower floors. Several grand rooms on the second floor will be refurbished for the use of readers and writers, who will be provided with carrels, computer stations, a lounge, and possibly a café. Most of the three million volumes from the old stacks will remain in the building, either in redesigned storage space or in shelving located under Bryant Park. But many—for the most part books that are rarely consulted and journals that are also available online—will be shipped to the library’s storage facility in Princeton, New Jersey, along with some of the holdings from the SIBL.

Most of the renovated library will look the same as it does today. Its special collections and manuscripts will remain in place, and readers will be able to consult them in the same quiet setting of oak panels and baronial tables. The great entrance hall, grand staircases, and marble corridors will continue to convey the atmosphere of a Beaux-Arts palace of the people. But the new branch library on the lower floors overlooking Bryant Park will have a completely different feel. Designed by the British architect Norman Foster, who will coordinate the renovation, it will suit the needs of a variety of patrons, who will enter the building from a separate ground-level entrance and may remain only long enough to consult magazines or check out current books, videos, and works in other formats. But it will also be used by scholars and writers who want to take home selected books that formerly could only be read in the building.

Will the mixture of readers who take home books and researchers who work inside the library, of premodern and postmodern architecture, of old and new functions, desecrate a building that embodies the finest strain in New York’s civic spirit? Some of the library’s friends fear the worst. A letter of protest against the plan has been signed by several hundred distinguished academics and authors, including Mario Vargas Llosa, the Nobel Prize–winning novelist, and Lorin Stein, the editor of The Paris Review. A petition of less-well-known but equally committed lovers of the library warns that the remodeling “will be ruining a functional element of its architecture—and its soul.” Blogs and Op-Ed pages have been sizzling with indignation.

The shrill tone of the rhetoric—“a glorified Starbucks,” “a vast Internet café,” “cultural vandalism”—suggests an emotional response that goes beyond disagreement over policy. Practically every critic has a story to tell about his or her personal encounter with the city’s most precious repository of culture; every story conveys the danger of defiling something sacred. Those responses deserve respect. Some of the criticism may be valid. But aside from the merits of the arguments, I think it important to recognize that the polemics are driven by passions that run deep in the city’s collective sense of self.

The problem, however, is fundamentally financial. For a great institution, the library has a small endowment: $830 million. The operating budget for the entire system—the eighty-seven branch libraries and the four research libraries—is $259.6 million in the current fiscal year. The city covers most of the budgets of the branches, but the operating costs of the four research libraries (the central facility at 42nd Street, the SIBL, the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem), which come to $113.9 million, are financed primarily from the endowment (30 percent), private contributions (22 percent), and earned income along with various other sources (19 percent). The city provides 21 percent, but it faces fiscal pressures of its own. It cut its contribution severely in the middle of last year, and it has reduced its support by 28 percent over the last four years. While the city contributes less, the library needs more, owing to the increasing costs of books, periodicals, and digital data. The result has been retrenchment. In 2008 the research libraries spent $15.2 million on acquisitions; in 2011 they spent $10.8 million.

Advertisement

One response to this inexorable pressure was the decision to sell the property occupied by the SIBL, which gets less use than was expected when it opened in 1996, and the Mid-Manhattan branch, whose dilapidated condition would require expensive renovation. Those sales might produce $200 million. Another $150 million has been committed by the city to help with the renovation of the building at 42nd Street. But this $350 million is only a prospect for funding in the future. It does not yet exist, and its existence is predicated on the realization of the renovation plan. The critics of that plan seem to think that the library has $350 million in the bank and that it will squander this nonexistent sum on an architectural extravaganza topped off with an unneeded café.

Another café is hardly needed at 42nd Street, where there is caffeine on every corner. But it is necessary to find a new location for the Mid-Manhattan branch, which has 1.5 million visitors a year. Norman Foster’s plan incorporates the Mid-Manhattan Library in the 42nd Street building without violating the integrity of the original design. By directing the flow of users through a separate entrance to a separate collection on the ground floor, it avoids disturbing the readers doing research on the second and third floors. But the space could be used differently. Another plan could devote less room to the general public and more for storing books. This objection lies at the heart of the critics’ case, and it deserves to be taken seriously.

Could a simpler plan retain the current stacks under the Rose Main Reading Room and still leave space for the Mid-Manhattan Library? Almost certainly not; and if the new branch library is not incorporated into the design, the Mid-Manhattan branch would have to be closed and renovated, an extremely expensive undertaking, or moved to new quarters somewhere else in the middle of the city, an even pricier alternative. Either way, the library would not acquire capital from its sale, and it would have no funds to pay for increased acquisitions or any improvements in the main building on 42nd Street. In addition to that building, it is now maintaining two large libraries, the SIBL and Mid-Manhattan, on some of the most expensive real estate in the world. By selling their buildings and incorporating their collections in a renovated structure at 42nd Street, the library will be able to put its finances on a sound footing and to satisfy its responsibilities to the public, among other things by hiring more librarians and devoting more funds to collections.

The downside of this plan is the downsizing of the storage space in the main library. But that space, where the shelving is a hundred years old and the lack of temperature control hastens the deterioration of brittle nineteenth-century paper, proved to be inadequate many years ago. The library has already moved almost half of its collections to ReCAP, the high-density, temperature-controlled storage facility in Princeton, which it shares with Columbia and Princeton universities.

According to the renovation plan, the Library will transfer to ReCAP up to 1.5 million more volumes from the three million currently stored in the old stacks at 42nd Street. Librarians will cull through those volumes in order to select those that have never or rarely been consulted during the past decade and those that can already be consulted in digital editions available online. The library estimates that over 90 percent of all the books and research materials requested by readers in a typical year—as indicated by call slips and other records—will remain at 42nd Street. A great many books will be shifted to the storage space under Bryant Park. That space could be expanded to hold more books, as the library’s critics argue. I believe they are right, although the expansion could cost about $20 million in funds that would not be available until the SIBL and Mid-Manhattan are sold and the renovation plan goes into effect.

Advertisement

Even if that money could be found, however, the underground stacks would soon be filled. No research library can expand its collections indefinitely without shifting an increasing proportion of them to offsite storage. The Library of Congress, Harvard, Yale, and the University of California have learned to accept that hard reality, and all house depositories located miles away from their main buildings. They have also cut costs in their offsite depositories by digital services such as scan-and-deliver, but copyright restrictions limit the use of digitization for lending purposes.

In fact, only one of the six largest American publishers, Random House, will now sell e-books to public libraries without restricting their availability to readers. HarperCollins caused a scandal by programming its e-books to self-destruct after they had been consulted by twenty-six library patrons, and some of the measures proposed by other publishers are even more restrictive.

For the foreseeable future, therefore, some researchers in the Rose Main Reading Room will have to depend on trucks going back and forth between Princeton and 42nd Street to get the books they need. The library’s critics rightly complain about past delays in what should be a twenty-four-hour service. Such delays must be eliminated, and the traffic along the New Jersey Turnpike will have to continue until a better solution is found.

Trucking as an answer to twenty-first-century problems of delivering books to readers? The time, expense, gas consumption, and environmental pollution make the current policy look short-sighted. We should find a way to take advantage of digital communication, despite the opposition of publishers and the obstacles of copyright laws. But digital enthusiasts rarely recognize the extent to which printed books (not journals) continue to dominate the marketplace. More books are produced each year than the year before. In 2009 more than a million new works were published worldwide, the vast majority in print, and in 2010 the total of new titles came to more than three million.

Research libraries cannot buy most of that output, but they should not ignore it on the grounds that, as current clichés put it, we now live in an “information age” and “all information is available online.” Libraries cannot fail to provide their readers with digitized material, especially in the form of e-journals and databases, and they cannot stop buying printed books. Therefore, they must advance simultaneously on the analog and the digital fronts. That problem, compounded by diminishing funds, underlies the predicament of the New York Public Library. It won’t disappear if we reject the renovation plan and retain a twentieth-century mode of operation.

Far back in the seventeenth century, the marquise de Sévigné, known for her wit and brilliance as a letter writer, reportedly remarked at a dinner table, “There are three important things in life. The first is to eat well, and—I have forgotten the others.” If asked to enumerate their priorities, the most assiduous users of libraries might say, “Acquisitions, acquisitions, acquisitions.” But libraries cannot acquire more material, in diverse areas and varied formats, without an army of bibliographers, selectors, catalogers, information technologists, and other skilled staff working in many ways to keep a complex institution running in high gear.

To keep up with the flow of publications, libraries must limit the scope of their acquisitions and cooperate with one another, for no research library can go it alone in the twenty-first century. For example, the New York Public Library does not buy heavily in the field of medicine—fortunately, as medical journals are egregiously expensive. (The Harvard Medical School spends $3 million a year on medical journals, which sometimes cost $30,000 for an annual subscription.) Nor does it acquire much in some professional fields such as law, engineering, and computer science.

Thanks to a recent agreement, Ph.D. students, full-time faculty, and anyone qualifying as an “independent scholar” can, with a reader’s card from the New York Public Library, gain admission to the participating libraries of Columbia and NYU, which have strong collections in medicine and other professional disciplines, and they can even check out printed material. In return, some members of Columbia and NYU have reciprocal rights to check out material—the arrangement is still in an experimental, pilot phase—from the main research library of the NYPL, even though it had never before permitted anything from its collections to circulate. This policy broadens the range of works available to its readers, but to the library’s critics it is another deviation from a tradition of keeping everything safely in the stacks at 42nd Street.

Whether or not this experiment succeeds, the library must adjust its acquisitions to fit its budget; but the renovation strategy will permit it to acquire more, especially in the humanities and the social sciences—in foreign literatures, philosophy, political science, and economics. In my view, it should concentrate on fields that give it a special character and make it stand out from other great libraries. It should reinforce its special collections and build to strength in areas like African-American studies, the performing arts, Judaica, and everything connected with the history and cultural life of New York.

Would such an acquisitions policy represent a retreat from the digital world? Certainly not. But cyberspace is so vast that the library should not attempt to venture into every corner of the Internet. It should buy the data sets and subscribe to the e-journals that correspond most closely to the needs of its readers. While respecting the constraints of its budget and the restrictions of copyright, it should digitize its own holdings and make them available to readers everywhere through open-access repositories. In the long run, the Internet will replace the New Jersey Turnpike as a conduit linking books to readers. But many readers have an immediate need for Internet service, not only at 42nd Street but in its eighty-seven branches. They are seeking jobs, and they cannot find them in the daily newspapers, which no longer carry many want ads. Therefore, they go to the nearest branch library, where they can get access to a computer and instruction on how to use it. These services to the city’s residents and its economy deserve more recognition.

Our concern for the collections in the grand edifice at the heart of the city should not lead to neglect of the library’s capillary system. By incorporating Mid-Manhattan into a renovated structure at 42nd Street, the library will enhance its mission to serve the people of New York at both a popular and an esoteric level, on the lower as well as the upper floors; and while lending its books more effectively, it will enrich the intellectual life of the city by improving and preserving its great research collections.

This Issue

June 7, 2012

Israel in Peril

The Loves of Lena Dunham