I read E.O. Wilson’s 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in 1979 while I was an undergraduate studying archaeology. Along with The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins (1976), Sociobiology transformed my view of the world, leading me away from a concern with the typology of stone tools and ceramics to deeper thoughts about human nature. As Wilson now expresses thirty-seven years later in the concluding pages of The Social Conquest of Earth, “History makes no sense without prehistory, and prehistory makes no sense without biology.” Whatever the specific arguments and ultimate merits of Sociobiology, it saved me from a life of measuring rim diameters and handle dimensions of ancient pots. Thank you, Professor Wilson.

At the time I did not appreciate E.O. Wilson’s stature as one of the greatest biologists of the twentieth century. I soon came to learn that in 1967 he was coauthor with Robert H. MacArthur of The Theory of Island Biogeography, which remains a key work for conservation today. I then learned that Wilson was the world authority on ants. Like so many others, I had gone through a “bug phase” as a boy and had even once declared to a primary school teacher that I wished to be an entomologist. I then began to appreciate the elegance of his prose. So E.O. Wilson was rapidly installed as an intellectual hero: someone who contributes to the highest-level theory about the nature of humanity, engages in fieldwork, analyzes data with meticulous erudition, and communicates to the layperson as effectively as to his scientific peers. Quite rightfully, he has been described as Darwin’s heir.

Now aged eighty-three, E.O. Wilson once described himself as never having grown out of his own childhood bug phase. Born in Alabama, he was awarded a Ph.D. in biology at Harvard in 1955, where he has remained for the entirety of his academic career, currently as Pellegrino Professor (Emeritus) in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. He has published a library of books and academic papers and been awarded a huge anthill of honors for his distinguished academic contributions to entomology, science, and the environment. These include the Crafoord Prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, often described as the equivalent of a Nobel Prize for biosciences. Wilson has been twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize and has had a profound influence on twentieth- and twenty-first-century thought and culture. He is a champion of the preservation of biodiversity.

Sociobology remains Wilson’s most influential work. It argued that whether dealing with ants or humans, social behavior has a biological basis. It promoted the theory of inclusive fitness, or kin selection, as originally developed by William Hamilton in the 1960s as a means to explain seemingly altruistic behavior while remaining consistent with Darwin’s principle of natural selection. In The Social Conquest of Earth, Wilson describes how he had become “enchanted by the originality and proposed explanatory power of kin selection.”

In simple terms, this explains behavioral acts that are detrimental to the reproductive success of an individual as being a means to promote the success of genetically related individuals and hence maximizing the number of shared genes within future generations. It is, according to this hypothesis, better for your own biological fitness to sacrifice your own life to save the lives of three of your children (each of whom has 50 percent of your genes) or, even better, seven of your grandchildren (each of whom has 25 percent of your genes). Wilson went on to collaborate with Charles Lumsden on Genes, Mind, and Culture: The Coevolutionary Process (1981), one of the first serious attempts to explore the interaction between biology and culture.

Sociobiology was enormously controversial, not only among those in the humanities and social sciences who saw a biologist impinging on their academic territory, but also among many of his fellow biologists. In 1986 Stephen Jay Gould lambasted it, along with Genes, Mind, and Culture, in the pages of The New York Review.* Others have voted it the most influential book on animal behavior of the twentieth century.

I tend toward the latter view. So how marvelous it felt a few months ago to have received an e-mail from the man himself asking if he could reproduce a diagram relating to human evolution from one of my own publications in his forthcoming book, The Social Conquest of Earth. What an honor to then be invited to review the book for The New York Review. And how awfully disappointed I have been.

The Social Conquest of Earth considers the evolution of the two types of organisms that have indeed made a conquest of the earth—humans and social insects, notably ants. These show some remarkable similarities in their social behavior: it is difficult, for example, to avoid imposing the terminology of “building cities” and “practicing agriculture” onto the behavior of leafcutter ants. Needless to say, there are also profound differences in human and ant social behavior.

Advertisement

As one would expect from E.O. Wilson, he finds memorable ways of making the comparisons: if one were to pack together the estimated ten thousand trillion ants living today, they would form a cube less than a mile on each side—the same size as would be achieved by log-stacking the seven billion humans. Both packages could be easily hidden away in a small section of the Grand Canyon. Elsewhere Wilson helps us imagine an alien visitor to planet Earth some three million years ago who is amazed at the social insects but dismissive of the australopithecines, which appear to be on an evolutionary road to nowhere.

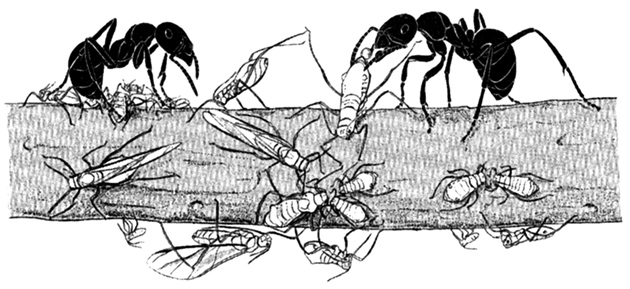

Social insects were fully evolved by 50 million years ago, with an evolutionary rate sufficiently slow to enable counter-evolution in other species—such as the sap-sucking insects that formed symbiotic partnerships with some ant species, or the pitcher plants that evolved to trap and digest ants—resulting in sustainable ecosystems. Homo sapiens, in contrast, only emerged 200,000 years ago, providing no time for the rest of the biosphere to adapt to its presence:

The rest of the living world could not coevolve fast enough to accommodate the onslaught of a spectacular conqueror that seemed to come from nowhere, and it began to crumble from the pressure.

Beguiling phrases such as this introduce the book, announcing a fascinating approach but setting off alarm bells in my mind about the picture of the human past being created, intentionally or otherwise.

The key similarity between humans and social insects is the characteristic of “eusociality,” defined by Wilson as “group members containing multiple generations and prone to perform altruistic acts as part of their division of labor.” This is, in fact, only characteristic of a small proportion of social insects, and of a mere 20,000 of the two million known insect species as a whole. The complexity of social life has certainly been a central theme in recent studies of human evolution, especially those concerning the brain, mind, and language. Although E.O. Wilson ignores most of that literature (at least it is not cited), he captures its general direction by describing human social strategies as being a “complicated mix of closely calibrated altruism, cooperation, competition, domination, reciprocity, defection, and deceit,” all of which depend upon feeling empathy, measuring emotions, and judging intentions.

As a path to eusociality, this is radically different from that taken by the instinct-driven, robotic insects. But once eusocial colonies are formed, Wilson contends, group selection becomes a key driver for both human and insect evolution. Group selection proposes that alleles—a particular form of a gene or group of genes—become fixed in a population because of the benefits they bestow on the whole group, regardless of the effects on the (inclusive) fitness of individuals—for instance, the benefit of being willing to sacrifice one’s life as a soldier.

Group selection was once popular among biologists, and then went entirely out of favor following critiques from William Hamilton and others who argued that social behaviors evolved entirely as the result of their benefits to the genetic fitness of individuals and those closely related to them—the theory known as kin selection, or inclusive-fitness theory. Group selection has recently made something of a return among a small group of biologists in the case of multilevel selection—a process combining selection at both the individual and group levels—for which Wilson has become a champion. As he writes:

In colonies composed of authentically cooperating individuals, as in human societies, and not just robotic extensions of the mother’s genome, as in eusocial insects, selection among genetically diverse individual members promotes selfish behavior. On the other hand, selection between groups of humans typically promotes altruism among members of the colony. Cheaters may win within the colony, variously acquiring a larger share of resources, avoiding dangerous tasks, or breaking rules; but colonies of cheaters lose to colonies of cooperators. How tightly organized and regulated a colony is depends on the number of cooperators as opposed to cheaters, which in turn depends on both the history of the species and the relative intensities of individual selection versus group selection that have occurred.

In drawing his evolutionary comparisons and contrasts, Wilson’s book alternates between sections devoted to humans and to social insects. There is an immense contrast of style and impact: the parts on humans are written as an external observer, a mere reviewer of literature, and suffer accordingly. The parts on social insects are the work of a key participant during the last half-century in research, enabling him to present a delightful blend of scientific account and personal experience.

Advertisement

The numerical facts are especially impressive: ants and termites originated 120 million years ago; one leafcutter ant can produce 150 million daughters. We learn how in 1967 Wilson received the first piece of fossil amber from the Mesozoic era, about 90 million years ago, to contain not one but two fossilized ants—twice as old as any seen before. It was, he describes, one of the most exciting moments of his life, so much so that he fumbled and dropped the piece. It broke into two—fortunately with one undamaged ant within each fragment. Elsewhere we read both how he enjoyed the sweet taste of scale insect [i.e., aphid] excrement during his hikes through the New Guinea rainforest and also his reflections when watching harvester ants on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, pondering how Solomon would have sat there watching precisely the same species at work.

Such accounts must be the tiny termite tip of a million and more stories that E.O. Wilson could relate. All readers will want more—fortunately there are plenty available within his other books, notably in Naturalist, his 1994 autobiography. Any more within the The Social Conquest of Earth would have been a distraction because Wilson is seeking to convey his bold theoretical perspective on the evolution of eusociality.

At the heart of the book lies Wilson’s rejection of inclusive-fitness theory in favor of group selection. This is not a trivial matter: inclusive fitness has been the preeminent theory in social evolution for half a century and Wilson himself describes it as a virtual dogma. Perhaps for that very reason he does not mince his words, writing about “the misadventure of inclusive-fitness theory” and how this is a “phantom mathematical construction that cannot be fixed in any manner that conveys realistic biological meaning.” A reader cannot fail to be impressed by such conviction coming from such a distinguished biologist.

Turid Hölldobler

‘A critical step in the rise of dominance of the ants is the partnerships they formed with sap-sucking insects, taking nutritious liquid excrement in exchange for protection against predators and parasites’; drawing of the European ant Formica polyctena and its symbiotic aphid partner Lachnus roboris, from Wilson’s The Social -Conquest of Earth

The case seems to be proved when Wilson explains how work with his colleagues Martin Nowak and Corina Tarnita in 2010 “demonstrated that inclusive-fitness theory, often called kin selection theory, is both mathematically and biologically incorrect.” He goes on to list some of its “basic flaws,” including “that it treats the division of labor between the mother queen and her offspring as ‘cooperation,’” when in fact “the workers are robots…that allow her to generate more queens and males.” A quick check of Wilson’s endnotes shows that the 2010 work was a publication in Nature, the world’s premier science journal. So, it must indeed be a confirmed conclusion: inclusive fitness incorrect, multilevel individual and group selection correct.

The only hint that the conclusion may not be quite as straightforward as stated comes three chapters later when Wilson begins to explain how he arrived at his alternative to inclusive-fitness theory. He writes, almost in passing, that

for many years I have conducted research in this field and most recently on a portion of the basic theory that has become the subject of heated controversy. The account to follow can be considered a dispatch from the scientific front.

Scientific bunker rather than scientific front would be far more appropriate. In 2011 an issue of Nature carried five “brief communications” that challenged the claims by Wilson and two other scientists—Nowak and Tarnita—that they had demonstrated inclusive fitness theory to be incorrect. These brief critical comments were co-authored by almost 150 biologists—a list elsewhere described as the “Who’s Who of social evolution studies.” Here too there was no mincing of words: “We believe that their [i.e., Nowak, Tarnita, and Wilson’s] arguments are based on a misunderstanding of evolutionary theory and a misrepresentation of the empirical literature” began the first of these communications, authored by 137 biologists from 103 institutions from around the world. Another of the notes states that Nowak, Tarnita, and Wilson “fail to make their case for logical, theoretical and empirical reasons.”

Now, it is not the purpose of this review to pronounce upon the validity or otherwise of inclusive-fitness theory and Wilson’s alternative theory of multilevel selection. Indeed, I would not presume to have the expertise to do so. Wilson develops his case by referring to scientific matters on which only experts can make judgment, such as the demise of the “haplodiploid hypothesis” and new mathematical work allegedly exploring inherent weaknesses in “Hamilton inequality.” I have, however, remained unimpressed by multilevel selective theory and persuaded by the weight of academic opinion in favor of inclusive fitness, dogma or otherwise.

My greater concern is about the responsibility of the scientist writing for the general reader, especially a scientist of Wilson’s academic reputation. Such readers, the type targeted by Wilson and his publisher, may never have heard of Nature and would be unlikely to consult endnotes. Such readers, owing to his failure to acknowledge the extent of opposition to his views, would be entirely misled into thinking that Wilson had indeed “demonstrated that inclusive-fitness theory, often called kin selection theory, is both mathematically and biologically incorrect.”

I recognize that there might be an issue of timing: The Social Conquest of Earth may have been so far into production by the time that the 2011 issue of Nature was published that citation was impossible. I suspect not: it was a March issue and Wilson’s book cites several 2011 publications. Even if this was the case, Wilson would have been quite aware of the vast weight of academic opposition to his views, since he has been promoting them since 2005 at least. I cannot avoid the impression that the manner in which Wilson presents his views verges toward polemic rather than providing a responsible work of popular science.

I am tempted to think the same about Wilson’s characterization of the archaeological record for human evolution. While he correctly identifies the key themes of human evolution—big brains, bipedalism, control of fire, shift to a meat-based diet, adaptive flexibility—his account is marred by a succession of factual errors. “Spear points and arrowheads are among the earliest artifacts found in archaeological sites.” No, the earliest artifacts are from around 2.5 million years ago, but spear points are not made until a mere 250,000 years ago and arrowheads might have first been manufactured no longer ago than 20,000 years. “Archaeologists have found burials of massacred people to be a commonplace,” while “archaeological sites are strewn with the evidence of mass conflict.” No, both are quite rare, especially in pre-state societies, and those that are known are difficult to interpret. “Homo erectus…was able to shape crude stone tools.” No, many of the hand axes made by Homo erectus are quite exquisite. “Axes and adzes [were] invented in the Neolithic” and “Neolithic toolmakers invented the concept of a hollow structure, with an outer and an inner surface.” No and no. These are elementary errors that could have been avoided by consulting any undergraduate textbook.

Elsewhere, the language Wilson employs provides a completely erroneous impression of the past. He remains wedded to antiquated phrases from a time when cultural evolution was envisaged as an inevitable progress toward Victorian values, as in the “dawn” of the Neolithic and the “ascent to civilization.” Wilson writes how Homo sapiens “slogged cautiously on foot” when dispersing from Africa; while this may have often been literally correct, the archaeological evidence—that Wilson goes on to accurately summarize—reflects an astonishingly rapid global dispersal with that of Australia at least involving the use of boats. On the next page, Homo sapiens have quickened their pace to become “skilled warriors” who outcompeted the Neanderthals. That phrase implies warfare and a distinct class of person within a tribal-based society specializing in combat: neither of these can find any supporting evidence in the Palaeolithic archaeological record.

Wilson’s factual inaccuracies and misrepresentations of the past are especially infuriating because in his own specialist field of insect evolution he meticulously attends to the data: “The key, researchers discovered, was not to rely on any logical assortment of premises of what might have happened…but to piece together from field and laboratory observations what actually did happen” (Wilson’s italics). Well, what must be right for the study of insect evolution must also be right for human evolution and Wilson should have followed his own advice with regard to archaeological evidence.

Wilson appears to be imposing a preconceived view about the role of warfare onto the archaeological evidence as a means to support his group selection theory. He blandly states that “wars and genocide have been universal and eternal, respecting no particular time or culture.” This serves Wilson’s end, because warfare is the epitome of group selection: individuals risking and often losing their own lives for the greater good—how else can we explain many of the young men volunteering to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan? But there is no archaeological evidence that warfare was pervasive in the human past, let alone “universal and eternal.”

Wilson writes that the archaeological evidence indicates that Homo erectus—and here we are dealing with up to 1.8 million years ago at least—no longer wandered through a territory but “selected defensible sites and fortified them, with some staying for extended periods to protect the young while others hunted.” Well, I know of no such evidence for defended and fortified sites, not only for Homo erectus but for pre-modern humans, and indeed for Homo sapiens until settled farming communities emerged a mere ten thousand years ago, long after the major work of human evolution had been completed.

The emphasis on fortification is unfortunate because the function of campsites at which some members of the group remained to care for young while others left to hunt and to gather in different parts of the landscape is indeed critical in human evolution. This was first identified in the seminal 1970s work of the archaeologist Glynn Isaac—who became a colleague of Wilson’s at Harvard. Isaac’s “Home Base and Food Sharing Model” (1978) should have been cited by Wilson since it provides considerable support to the equivalence he draws between human campsites and insect nests.

The formation of the nest, especially a defensible nest, is for Wilson the critical second stage in the five-stage process for the evolution of eusociality among insects. Nest formation follows the formation of groups of what had previously been solitary individuals, which might arise for a variety of ecological reasons such as localized distributions of food. The third stage is the “knockout of dispersal behavior” so that multiple generations begin to cohabit rather than each generation creating their own new nest. This might arise, he suggests, by a single genetic mutation that cancels out the instinct to disperse.

Fourth stage: “As soon as the parent and subordinate offspring remain at the nest, as with a primitively social family of bees or wasps, group selection proceeds, uniquely targeting the emergent traits created by the interactions of the colony members.” As such, the colony becomes a “superorganism”—the title of his 2009 book with Bert Hölldobler, accurately subtitled “The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies.” The superorganism now competes with other colony superorganisms and hence becomes subject to further group-level selection, providing the fifth and final stage for the evolution of eusociality—at least according to E.O. Wilson. He acknowledges that this is all subject to experimental verification.

But what of human eusociality? While Wilson argues that the first three of his stages may be applicable to human evolution, he recognizes that the final two stages could have only happened in insects and other invertebrates. So the final section of his book returns to humans with a few short chapters that attempt, no less, to explain “What Is Human Nature?,” “How Culture Evolved,” “The Origins of Language,” “The Origins of Morality and Honor,” “The Origins of Religion,” and “The Origins of the Creative Arts,” before ending with “A New Enlightenment.”

Even for a double Pulitzer and Crafoord Prize winner such as Wilson this is too much to take on, especially as there have been several complete books published on each of these topics in recent years. There has been a great deal of work on these issues from an explicitly evolutionary perspective, some of which Wilson appears to be unaware of—such as that about the evolution of music and its relation to language. Hence one gets a taste of the issues involved but without much satisfaction, always sensing that one is engulfed by the enormity of the issues—perhaps rather like E.O. Wilson sampling the aphid excrement below the canopy of a rainforest.

The topic that I found to be most sweet—or was it bitter?—was that of morality. Wilson has a straightforward view deriving from his belief in multi-level selection that he repeats throughout his book and is best expressed on page 56. In humans, he writes,

An unavoidable and perpetual war exists between honor, virtue, and duty, the products of group selection, on one side, and selfishness, cowardice, and hypocrisy, the products of individual selection, on the other side.

Multilevel selection has left us in a state of endemic mental turmoil. He acknowledges the complicating issue that the social world of each modern human is not a single tribe but a system of interlocking tribes, hence duty to one might equate to selfishness toward another. Putting that acknowledgment aside, he seems to entirely ignore both the moral bankruptcy of unerringly conforming to group norms and the virtue of those who are prepared as individuals to challenge the consensus.

How astonishing that he should have such views. E.O. Wilson is a man who has shown immense duty to his own individual beliefs by opposing the consensus of his own tribe, his scientific peers. He did this in 1975 when he published Sociobiology and again three decades later when he began to challenge the veracity of inclusive fitness. Bravely, he brought opprobrium upon himself by an utterly unselfish act of opposing the members of his academic tribe—surely this could only be a product of individual-level rather than group-level selection. How could E.O. Wilson of all academics write a book with a chapter entitled “Tribalism Is a Fundamental Human Trait”? His whole career, the man himself, falsifies his own views about human morality. It is often said that you are only as good as your last book. That too is now falsified: E.O. Wilson is far better than The Social Conquest of Earth. For me, he remains an intellectual hero.

This Issue

June 21, 2012

Real Cool

How Texas Messes Up Textbooks

Mothers Beware!

-

*

Stephen Jay Gould, “Cardboard Darwinism,” The New York Review, September 25, 1986. ↩