Wilkie Collins, the master plotter of Victorian fiction, famously attributed his literary success to the old music hall adage “Make ’em laugh, make ’em cry, make ’em wait.” In Canada—his first novel since The Lay of the Land (2006)—Richard Ford emphasizes the third element of that snappy precept. While Canada sets up numerous scenes that teeter on the edge of the comic, they usually slide into the pathetic, macabre, or hallucinatory. The novel’s forlorn tone—of thoughts that lie too deep for tears—quite naturally grows out of the narrator’s painful recollections of a close family destroyed by a foolish act of parental desperation. Ford really excels, however, in his virtuoso command of narrative suspense. He makes us wait.

The two main actions of Canada are announced in its opening lines: “First, I’ll tell about the robbery our parents committed. Then about the murders, which happened later.” Such sensational words, even presented with matter-of-fact understatement, will grab anyone’s attention. But on the surface, they would also seem to be revealing too much, arguably wrecking the novel’s plot. Yet Ford is nothing if not sensitive to his sentences, emphasizing in many interviews the great care he takes over the subtleties of sound and sense. Nobody, he says, looks longer at his words than he does or calculates more precisely their effects.

So readers should also look again. Note that pronoun “our” instead of “my”—this is, in some way, going to be a story about siblings. Notice, too, that Ford’s narrator dances over whether the robbery is successful or not. Finally, he carefully avoids saying who is murdered and by whom. Ford’s real interest doesn’t lie in the robbery or the murders per se so much as in the events leading up to the crimes and to their aftereffects on those siblings. We know that the robbery and the murders will take place. But when? And how? And what will happen subsequently? So we attend, we observe, we prepare for the inevitable. Readers may recall that Gabriel García Márquez strikingly employed just this technique in his novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

In fact, Ford virtually flaunts his artistic chutzpah by the regular insertion of “now-you-don’t-see-it, now-you-do” flourishes throughout his narrative: in the middle of a page of slow, rich description or of slightly ponderous meditation, he will casually drop in a key fact, almost in passing, like a little nosegay thrown to the surprised crowd. After his opening paragraph, for instance, he introduces the Parsons family: Retired Air Force Captain Bev Parsons, his wife Neeva, and their fifteen-year-old twins, one a girl named Berner. But Ford withholds full identification of the other twin, the book’s narrator. (We wonder, though, about all these distinctly odd, almost transgendered names.) Then, just when most readers will have concluded that Ford simply isn’t going to reveal the name of the narrator, Bev addresses his son as “Dell.” Ford defers this information until page 77, at the beginning of Chapter 12.

Similarly coy tantalizers and throwaway revelations are scattered like stick-it notes throughout the novel. On page 20 Dell—we’ll call him that, though we don’t yet know his name—reveals that he learned about his parents’ crime from the newspaper and from what people told him at the time:

And, of course, I know some particulars because we were there in the house with them and observed them—as children do—as things changed from ordinary, peaceful and good, to bad, then worse, and then to as bad as could be (though no one got killed until later).

Again, on page 54, Dell mentions his mother’s “Chronicle of a Crime Committed by a Weak Person,” adding that “possibly she thought a well-written version of their story would offer a future for her when she got out of prison—which she never did.” At this point, the reader still doesn’t know how Neeva was captured or why she never left prison. Only on page 103 does Dell let slip—parenthetically, between a set of dashes, as if it were an afterthought of little consequence—that “she’d taken her life in prison.” (But not how: we’ll have to wait even longer to learn that.) Such nuggets, like flecks of gold in a miner’s slurry, elicit a jolt of surprise or satisfaction each time they occur.

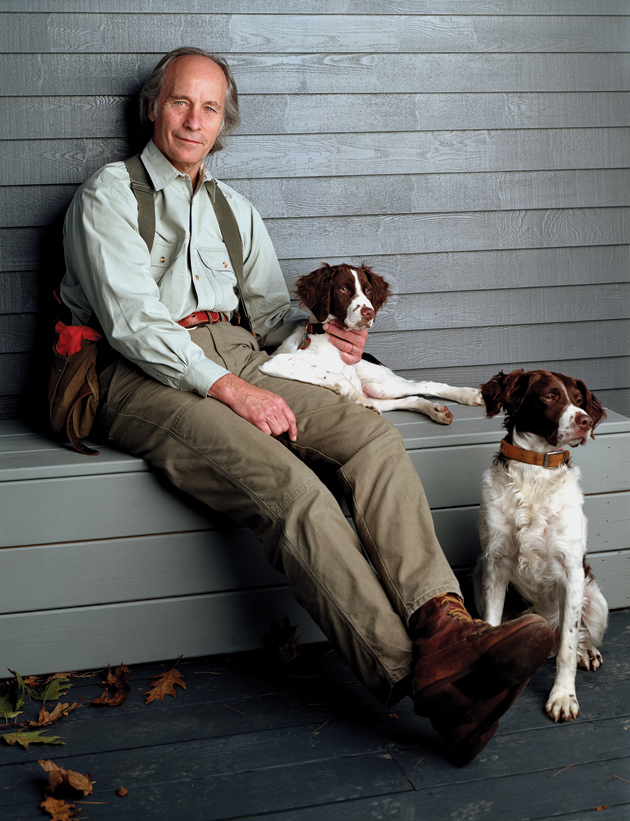

In short, Ford is deliberately playing with his reader, almost showing off: look how much I can divulge, spin out, or hold back and still keep you hooked. Some readers may be irritated by this technique as overly contrived; most, however, will find it dexterous and artful. Whichever the case, Ford leaves us in no doubt about his iron grip on his book’s pace and rhythm. Years ago, the novelist was asked about his relationship to his characters and he replied, “Master to slave. Sometimes I hear them at night singing over in their cabins.” That’s a daring analogy and an apt one. Ford’s novels may sometimes look loose and baggy, but that casualness is rigorously calculated.

Advertisement

The first half of Canada is set in 1960, in Great Falls, Montana. (This is a geography made familiar to readers in Wildlife, Ford’s 1990 novel about a teenage boy discovering his mother’s adultery and its consequences.) Bev Parsons, an easygoing Southerner, “big, plank shouldered, talkative, funny, forever wanting to please anybody who came in range,” has taken early retirement from the Air Force, possibly because of a scandal over some stolen beef. Like other Ford heroes, in particular Frank Bascombe of The Sportswriter (1986), Bev is a dreamer, a somewhat feckless self-mythologizer who “existed in another world,” who relied on “his easy scheming nature, his optimism about the future, his charm.”

His wife, Neeva, is the thirty-four-year-old daughter of Jewish immigrants: small and bony, she wears spectacles, reads French poetry, and is more intellectual than her husband. Neither of their fifteen-year-old twins is physically prepossessing: Berner is skinny, flat-chested, bossy, and clearly bound for trouble. Dell is compact, neat, with “pretty” features, mainly interested in school, chess, and learning to keep bees. The family sticks to itself, refusing to interact with the town or otherwise “assimilate.”

After leaving the service, Bev finds a job selling cars, bringing home various new models, including a flashy Coronet, fully loaded with “push-button drive and electric windows and swivel seats, and also stylish fins, gaudy red tail-lights, and a long whipping antenna.” As usual, Ford carefully embeds his story in its time, in this instance 1960, as well as place. Characters talk about the Seattle Space Needle, chess champion Bobby Fischer, the Rexall Drugstore, Bab-O cleanser, “the spy plane incident, Francis Gary Powers, the ‘Winds of Change,’ the revolution in Cuba, Kennedy being a Catholic, Patrice Lumumba,” and the recently executed murderer Caryl Chessman. Dell reads the World Book Encyclopedia and keeps some Charles Atlas muscleman books in his bedroom, along with copies of his “Rick Brant science mysteries.” Obviously nothing bad will ever happen in such an ordinary, familiar world. As Dell ruefully observes, “To me, it’s the edging closer to the point of no return that’s fascinating…. How amazingly far normalcy extends.”

While the characters in Canada spring to life through their distinctively individual voices, Ford tends to shy away from prolonged conversations, often preferring reported speech. Instead he lavishes his most intense attention on descriptions of people and locales. For example, early in the book, Bev drives his two children out into the country, passing the dilapidated houses of some Indians:

The first house had no front door or panes in its windows, and the back portion of it had fallen in. Parts of car bodies and a metal bed frame and a standing white refrigerator were moved into the front yard. Chickens bobbed and pecked over the dry ground. Several dogs sat on the steps, observing the road. A white horse wearing a bridle was tethered to a wooden post off to the side of the house. Grasshoppers darted up into the hot air the car displaced. Someone had parked a black-painted semi-trailer in the middle of the field behind the house, and beside it was a smaller panel truck that had HAVRE CARPET painted on its side.

Those words “Havre Carpet,” which mean nothing to Dell and Berner, deliver a little wave to attentive readers. By this time, we know that just such a truck delivers the stolen beef.

Of course, this isn’t just any casual drive in the country: Bev is in big trouble and his latest get-rich-quick scheme has begun to fall apart. The Indians, volatile and dangerous, are angry over a failure to be paid properly for their contraband beef, and on Sunday morning one appears outside the Parsons’ home. Dell and Berner have been playing badminton:

It was just when the Lutherans’ bell had begun ringing that an old car pulled up in front of our house and stopped. I thought the driver—a man—was one of the Lutherans and would get out and go across to the church. But he just sat in the old, crudely painted red Plymouth and smoked a cigarette as if he was waiting on something or someone to start paying attention to him.

Eventually, the man climbs out of the car:

At almost the same instant my father came out the front door, still in his Bermudas, and went down the concrete walk as if he’d been watching to see if the man would get out. Now that he had, something immediate needed to be done about it.

We both heard our father say, “Okay, whoa. Whoa-whoa-whoa-whoa,” as the man came slowly up the walk. “You don’t need to be showing up here now. This is my home,” he said. “This is going to get settled.” Our father laughed at the end of saying that, though nothing seemed funny.

The stranger turns out to be Marvin Williams, known as Mouse. He and Bev talk quietly, as the children watch. Only at the end of the chapter does Dell reveal what was said and its consequences:

Advertisement

It was probably, I came to think, in the hours after the Indian, Williams-Mouse, stood in our yard and threatened to kill our father, and possibly kill all of us if he wasn’t paid…, that our father began putting together thoughts of needing to do something extra-ordinary to save us, which turned out to be thoughts about robbing a bank—about which bank to rob, and when, and how he could enlist our mother so he could lessen the likelihood anyone would find out, therefore keeping them out of jail. Which didn’t happen.

Over the next one hundred pages we learn about the preparation for the robbery, then how it took place, and what occurred afterward. The afterward is all-important. As Ford told an interviewer many years ago, “I’m always interested in what happens after the bad things happen…because it’s a proving ground for drama.”

Throughout Canada Dell repeatedly emphasizes that his parents were “regular” folks, not born criminals, and that both of them, especially his mother, should have used common sense and just stopped the whole business before it got out of hand. But, he speculates, the idea of the robbery quickly passed out of this world into an alternate dream-reality: Bev “wanted more than any $2,000 to pay off Indians, since he could have settled that without robbing a bank. The more—whatever it was—was what the robbery was about for him.”

For one thing, the extra money, once the Indians had been paid, would allow him to care more responsibly for his family. However, he was also caught up in the romantic imagery of the young outlaws Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. As Dell says: “Some people want to be bank presidents. Other people want to rob banks.” But what about Neeva? Dell concludes:

My guess is—fifty years gone past now—that…Neeva came to the remarkably mistaken conclusion that robbing a bank was a risk that would facilitate things she wanted.

These things included the wherewithal to leave Bev and start a new life with her children. None of this was to be. (Notice, by the way, that the phrase “fifty years gone past” gives our first clear indication of when this story is being written.)

And what of the two children? After their mother and father return from their mysterious overnight excursion, both siblings feel puzzled, confused, and finally traumatized by their parents’ increasingly crazy behavior. After all, the nerdy Dell wants nothing more than an ordinary life, to go to high school, learn Latin, join the chess club, set up a beehive in the backyard as his science project. To him, bees represent what he longs for: “Everything in the hive was an ideal, orderly world.” His father, by contrast, views the insects differently: “Bees gang up on you is what I’ve heard.”

Given Berner’s feistiness, she just wants to run away, possibly with her Mormon boyfriend Rudy, a figure both threatening and comic. According to Rudy:

Mormons had invented a secret language…that they only spoke to each other. They planned to enslave Catholics and Jews, and Negroes were to be sent to Africa or else executed. Washington, D.C., would be burned to the ground. If you left the Mormon Church, they hunted you down and brought you back in chains.

Before long, Dell is himself worried about being hunted down and brought back in chains. Halfway through Canada, the dreams of the Parsons family have all been shattered. A desperate Neeva, however, has made plans to have a friend smuggle her son into Saskatchewan. Crossing the border symbolically inaugurates what the boy comes to call “reverse thinking.” As Dell stresses:

It’s been my habit of mind, over these years, to understand that every situation in which human beings are involved can be turned on its head. Everything someone assures me to be true might not be. Every pillar of belief the world rests on may or may not be about to explode…. I simply take nothing for granted and try to be ready for the change that’s soon to come.

Given its timing—just when the “Canada” section of the novel is about to begin—how are we to take this passage? Has Dell begun to lose his naiveté? Are we being alerted to the unreliability of his initial impressions? Is the second half of the book a “reverse” of the first half?

For a while the boy ends up living in conditions almost precisely like those of the Indians he observed back in Montana. Once Bev had been a bombardier, now a bomb plays an important role in this new section’s backstory. Almost nobody in Saskatchewan is quite what he or she seems. The apparently civilized turn out to be heartlessly callous; a Faulknerian lowlife possesses strange wisdom and dignity. One certainly doesn’t forget the dwarfish Charley Quarters—half French, half Indian—who dresses in cast-off clothes, wears rubber boots, and pulls back his black greasy hair with a woman’s rhinestone barrette.

This roustabout works for a mysterious American exile named Arthur Remlinger, who has agreed to take Dell into his employ, first as an assistant to Charley, later as a flunky at his hotel in Fort Royal. While Charley is a terrifically competent hunter and woodsman, he also wears rouge, perfume, and lipstick and goes around saying things like “A lot of brave men have head wounds” and “It’s hard to go through life without killing someone.” Dell feels, quite understandably, unnerved by his company.

Still, for a while Ford leads the reader to expect a Captains Courageous–style transformation, as the sissified city boy learns manly outdoor skills. Moreover, it would appear that the thirty-eight-year-old Remlinger—who is the same age as Bev Parsons—is being set up as a new father to Dell. The boy, drawn to the eccentric and dandyish hotel owner, even imagines himself as his “special son.” But there are muddy depths to Remlinger, and a disturbing “absence, one he was aware of and badly wanted to fill.” Dell concludes that

he needed me to do what sons do for their fathers: bear witness that they’re substantial, that they’re not hollow, not ringing absences. That they count for something when little else seems to.

Dell’s experiences in Saskatechwan turn out to be as hallucinatory—as detritus- and death-strewn and weird—as those of Jim in the war-ravaged Shanghai of J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun. In the middle of nowhere Dell discovers a school for wayward girls. He also explores the abandoned town of Partreau:

Back in the cluttered weeds and dooryards were rusted, burnt-out car relics and toppled appliance bodies and refuse pits full of cabinets and broken mirrors and patent medicine bottles and metal bed frames and tricycles and ironing boards and kitchen utensils and bassinets and bedpans and alarm clocks all half-buried and left behind. To the back of town, south and square to the fields and olive rows, stood the remains of an orchard, possibly apples, that had failed. The dried trunks were stacked husk on husk, as if someone had meant to burn them or save them for firewood, then had forgotten. Also, there I discovered the dismantled, rusted remnants of a carnival—red, mesh-hooded chairs of the Tilt-a-Whirl, the wire capsule of the Bullet, three Dodge-em cars and a Ferris Wheel seat, all scattered and wrecked, with spools of heavy gear chain and pulleys, deep in the weeds with a wooden ticket booth toppled over and once painted bright green and red, with coils of yellow tickets still inside.

This is, metaphorically, a world of wrecked dreams, of people unable to adjust to “normal” society, a purgatory showing forth what Ford has called, in summarizing his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Independence Day (1995),

the eventual sterility of cutting yourself off from liaisons with other people, from attachments, affinities, affiliations with other people. Finally the end of the line for independence is sterility.

Here, in Front Royal, Saskatchewan, we meet a bar pickup named Betty Arcenault (and wonder if she is related to Bascombe’s onetime girlfriend Vicki Arcenault). Here people have read Major Douglas (whose theories of social credit undid Ezra Pound). Here a stranger unexpectedly turns to Dell and asks, “You don’t have any interest in Hitler, I guess, do you?” Meanwhile, foreshadowing increases. Dell has promised to tell us about the murders, and we won’t have to wait much longer.

About the killings Dell Parsons has thought long and hard, largely because they

seem connected to my parents’ ruinous choice to rob a bank—with me as the constant, the connector, the heart of the logic. And before you say this is only fiddling, fingering tea leaves to invent a logic, think how close evil is to the normal goings-on that have nothing to do with evil. Through all these memorable events, normal life was what I was seeking to preserve for myself. When I think of those times—beginning with anticipating school in Great Falls, to our parents’ robbery, to my sister’s departure, to crossing into Canada, and the Americans’ death, stretching on to Winnipeg and to where I am today—it is all of a piece, like a musical score with movements, or a puzzle, wherein I am seeking to restore and maintain my life in a whole and acceptable state, regardless of the frontiers I’ve crossed.

I know it’s only me who makes these connections. But not to try to make them is to commit yourself to the waves that toss you and dash you against the rocks of despair. There is much to learn here from the game of chess, whose individual engagements are all part of one long engagement seeking a condition not of adversity or conflict or defeat or even victory, but of the harmony underlying all.

Near the end of Canada, Dell—who we already know will become a schoolteacher—lists the books he likes to use in his classes: Heart of Darkness, The Great Gatsby, The Sheltering Sky, The Nick Adams Stories, The Mayor of Casterbridge. He explains that

my conceit is always “crossing a border”; adaptation, development from a way of living that doesn’t work toward one that does. It can also be about crossing a line and never being able to come back.

Many characters in Canada cross the line and never do come back. But Dell adapts, choosing a safe and cautious existence. Only in the novel’s short coda do we learn more about his sister Berner. She has followed a quite different path in a raggedy life strewn with mistakes, adventures, and unhappiness. In effect, she has remained resolutely, violently American, unlike her brother, who clings to a reasonable, measured contentment. “Impersonation and deception,” Dell tells his students, “are the great themes of American literature. But in Canada not so much.” To quote the worldly wise Selma Jassim (from The Sportswriter): “A pleasant, easy existence staunched almost any kind of unhappiness.”

Each part of Canada is superb in its own way, and, as Dell tells us, there are links between them. Nonetheless, the two halves differ as much as the Parsons twins do. While the Montana chapters might be likened to a modernized western (Indians, cattle rustling, a bank holdup), the second half presents a Southern Gothic vision of the North, complete with the depraved half-breed servant, the elegant, corrupt master, dark family secrets, good ol’ boys drinking, whoring, and hunting, and finally the awaited revenant from the buried past.

“Stories,” Ford has stressed, “should point toward what’s important in life.” He himself has long been drawn to the theme of “secular redemption,” that “through the agency of affection, intimacy, closeness, complicity,” we come to feel “like our time spent on earth is not wasted.” A serious artist, Ford is regularly willing to risk sounding earnest or even portentous. While his fiction invariably delivers a lot of pleasure, it’s clear that he’s not just writing for fun.

Thus Canada ends with a somberly august peroration, as the sexagenarian Dell reflects, one last time, on his childhood and the hard lessons he learned way back in 1960:

My mother said I’d have thousands of mornings to wake up and think about all this, when no one would tell me how to feel. It’s been many thousands now. What I know is, you have a better chance in life—of surviving it—if you tolerate loss well; manage not to be a cynic through it all; to subordinate, as Ruskin implied, to keep proportion, to connect the unequal things into a whole that preserves the good, even if admittedly good is often not simple to find. We try, as my sister said. We try. All of us. We try.