Adela, Bernice, and Charna, the youngest—all gone for a long time now, blurred into a flock sailing through memory, their long, thin legs streaming out beneath the fluffy domes of their mangy fur coats, their great beaky noses pointing the way.

They come to mind not so often. They come to mind only as often as does my mother, whose rancor toward them, my father’s sisters, imbued them with a certain luster and has linked them to her permanently in the distant and shadowy arena of my childhood that now—given the obit in today’s Times of violinist Morris Sandler—provides most of the space all four of them still occupy on this planet.

I was preparing to eat. I’d plunked an omelet onto a plate, sat down in front of it, folded the paper in such a way that I could maneuver my fork between my supper and my mouth and still read, and up fetched Cousin Morrie’s picture, staring at me. Of course I didn’t exactly recognize Morrie, and if I hadn’t glanced at the photo again and been snagged by the small headline, I might have gone on for years assuming that my only known remaining relative was out there somewhere.

The tether snapped and I shot upward, wafting around for a moment outside of Earth’s gravitational pull, then dropped heavily back down into my chair next to my supper, cracks branching violently through my equanimity, from which my family, such as it was, came seeping. I picked up the phone, I put it down, I picked it up, I put it down, I picked it up and dialed, and Jake answered on the first ring. “Yes?” he said wearily.

“Oh, Christ,” I said, and hung up.

I dialed again and again he answered immediately. “My cousin died,” I said.

“Your cousin?”

“Cousin Morrie. The violinist.”

“Did I ever meet him?” Jake said.

“No,” I said. “You never met him. Though you once saw a letter he—but wait!” my heart started to thud around clumsily, like a narcolept on a trampoline. “Why are we talking about you? This is about my cousin.” I started to read: “‘Morris Sandler, violin virtuoso, dies at 66. Sandler was known as—’”

“‘At 66,’” Jake said. “At 66, at 93, at 14, at 75—at 66 what? Those numbers just aren’t the point, are they.”

“Have you been drinking?”

“I’ve been working. I’m at the lab. I’m sorry about your cousin. I didn’t remember that you had one. You weren’t close to him, were you?”

I held the receiver away from me and stared at it.

He sighed. “Listen, do you want me to come by?”

“No,” I said, though I did want him to come by. Or, I fiercely wanted him to come by, but only if he was going to be a slightly different person, a person with whom I would be a different person—a pleasant, benign, even-tempered person. “I’m sorry I called. Again. I’m sorry I called again.”

“I wasn’t being flippant,” he said. “It just really suddenly struck me how primitive it is to measure the life of a human being by revolutions of moons and stars and planets. Anybody who still believes that our species is the apex of creation should—”

“How do you suggest we measure the life of a human being?” I said. “By weight? Would that be less primitive? By volume? By votes? By distance commuted? By lamentations? By beauty?”

He sighed again.

“Sorry,” I said. I glanced around the room, the fading traces of Jake, still floating starkly against his absence. I love you, we still said to one another, but after a year and more of separation it seemed less and less likely that either of us would want him to move back in, and a vacuous, terminating, formal tone of apology clung to that word, “love.” It was like a yellow police tape at a crime scene. “Jake?”

“What?” he said. “What do you want me to do?”

I hung up again, tossed the omelet into the trash, drank up my wine to the accompaniment of the ringing phone, poured myself another glass, Friday night, why not, and flopped down on the couch with the newspaper as the ringing of the phone broke off.

Judging from the photo, Morrie, my only cousin, eventually came to look just like his mother, Adela. But as he seems to have had a wife at some point and was apparently a respected collector of original classical scores as well as a technically peerless musician, the resemblance—despite my mother’s gloatingly doleful predictions—must not have demolished him entirely. He was obviously something of a mechanism—evidently he had amassed an enormous collection of train timetables in addition to the scores—as my mother always claimed, but that is unlikely to have been the consequence of having inherited his mother’s nose.

Advertisement

As it happens, when I was five or six and Morrie was seventeen or eighteen, he still had blond curls and a flat face with an expression I interpreted as soulful—a plaintive, baffled look, as if someone had just snatched an ice cream cone from his hand, and I had private hopes that he might be an angel, though by the time I was able to formulate the thought, I had the sense to refrain from asking my friend Mary Margaret Brody, who could have told me for sure. In any event, at some point I commit the faux pas of announcing in the presence of both my mother and Aunt Adela that I will be marrying Morrie when the time is right. “Well, it’s your life,” my mother says, “but don’t blame me when your children turn out feeble-minded.”

“Oh, that reminds me—” my aunt says distractedly to my mother. “Did I forget to mention? Morrie is graduating summa.”

My mother snorts. “You did not forget.”

Later, when we are alone, my mother adds that in civilized parts of our country only criminals marry their cousins, and furthermore, she expects me to do better than someone in that family. Despite Adela’s boasting, she says, despite the grades and the honors, Morrie has an exceptionally mediocre mind. It would be a miracle if he did not graduate summa from the tenth-rate college he is attending. The only reason he gets all those good grades in the first place is because he is able to memorize a freakish number of pointless facts. Naturally Adela finds this remarkable, as she can’t even remember where she put her head.

“I expect you to outshine Morrie by far,” my mother says. “You have much more to offer—much more. Your problem is that you don’t apply yourself.” Morrie’s capacious but unnuanced memory was acquired from his father, who was so rigid himself that he toppled over and died at the age of forty, my mother tells me. Her impersonally disapproving gaze is directed, as she speaks, at a pair of stockings she is inspecting for runs. “And remember,” she says, “Marry in haste, repent at leisure.”

My aunts are the frequent topic of discourse when I visit my mother in her bedroom, where she sits in her big chair, her feet in a basin of water, cloudy with salts and potions. The feet are lumpy, whorled, fish white, and riveting—trolls’ feet, the toenails thick and yellow, mottled with blue. A fungus, she says. Blue and red graphs of her suffering run up and down the suety legs, which her hiked-up dressing gown exposes all the way to the thighs.

A slice of cucumber sits over each of my mother’s closed eyes to reduce puffiness. And as she talks, I concentrate on spreading out my substance, making myself spongy to absorb the puffiness into myself, to absorb the pain radiating through her feet and legs and back. She works nights in the cloakroom of the club, standing all the time, and that’s what accounts for the conspicuous veins that I find so fascinating but which, she explains to me, are disfiguring.

A familiar cold metal hand closes around my heart and squeezes: my mother is on her feet hour after hour, day after day, so that I will someday go to college. What an abundance of opportunities lies before me, for failure! Sitting on my mother’s dressing table is a framed photo of a lovely girl. In this photo a heap of shining ringlets somewhat obscures the shape of the girl’s head, but there are the distinctive, long, shiny-lidded eyes, their pale, nearly transparent disks of irises plausibly green though represented in black and white, with tiny, shocking dots at their centers. The expression, too, is well known to me, though the girl’s suggests a mischievous rather than a malevolent irony.

It is hard to believe, but there is the evidence—always building to the same, ringing summation: a lack of advantages ate the lovely girl alive and emitted in her place someone shaped like a melting pyramid, at the apex of which is a head—as wide and oval as my aunts’ heads are long and oval—adorned at the ends with little frilly ears and topped now with a careful display of durable-looking, reddish curls, someone whose feet must sit in a basin.

I reach for my mother’s hand and hold it tightly.

Advertisement

“What’s the matter with you?” she says, but she allows my hand to stay clasped around her fingers, even though it is clammy and disagreeable.

Flower to fruit to bare branch, sun to wan star—who am I to complain? The laws are the laws. I shake my head, and clear a way for my answer. “Nothing.”

“Your cousin Morrie was a beautiful child. My first thought when I saw him and Adela was to wonder if he wasn’t adopted. Ah, well—no one in that family need worry about being loved for beauty alone,” my mother says, impressing upon me the power of euphemism. In fact my aunts, with their coarse black hair, narrow faces, huge, vivid features, and long legs extending elegantly from their bell-shaped furs look nothing like the other people in our little city—the Polacks and Litvaks, my mother calls them.

“What is this ludicrous obsession with aliens from outer space?” my mother says. “I am not taking you to Women of the Prehistoric Planet, so you can just forget about that.” Aliens from outer space, she tells me, are, like Santa Claus, the invention of people too fey, too shallow, or too fearful to grapple with reality, or who stand to profit.

Still, I reason, surely there’s no way to be 100 percent certain, especially because any aliens who came to our planet would take care to look as much like humans as possible, though it would be logical that they would get things just a bit wrong.

Also, it would be rash to judge the intentions and purposes of aliens. There could be aliens among us who were sent only to observe, or even to help, not to meddle. Or—and these are the contingencies that seem most likely—aliens who escaped to the refuge of our planet from the terrors of their own or, conversely, who had been expelled, as a punishment, from the haven of their planet and condemned to the terrors of ours.

What is certain is that my aunts’ house, which is draped in the shadows of the massive trees that surround it, has a stagey, provisional feel, as if it were an illusion produced by powerful, distant brainwaves, and I can’t shake off the thought that the house dematerializes at night—its own form of sleep when its inhabitants are sleeping. I understand that the house is made of brick rather than brainwaves—it just has to be—but still, I brood about it: hypothetically, what would the point of the illusion be? It would be…to get you to think that some particular thing was real, or else to get you to think that some particular thing was not real.

I once tried to describe to Mary Margaret, who had just gotten two great big, pretty, rabbity, new front teeth and did not look entirely convincing herself, the way the house always appeared to be quivering in a twilight of its own and how you had to climb through shadows just to get through the door. “Do they have human sacrifices there?” she asked me, wide-eyed.

“Of course not!” I told her, looking frantically around for a receptacle, as I sometimes throw up when something unexpectedly upsets me. “My aunts would never do anything like that—they’re so nice!”

But I always tingle with anticipation at the thought of the house, of parting the veiling shadows to explore its mysterious interior, and also because Aunt Charna might give me a present when I next visit.

“Fortunately,” my mother continues, “beauty is not the only thing in life. Your Aunt Bernice and your Aunt Adela are honest and hardworking. And we have to be grateful, because they’ve taken trouble over you. Your Aunt Charna has some style, at least. That one wouldn’t be half so homely if only she’d do something about the nose!” She looks sharply at me and then sighs.

Sometimes my mother takes me to the club where she works, and even though it’s exhaustingly dull to play in the cloakroom all day, I can bring my paper and colored pencils, and there is a lurid appeal in the ambiguous suggestions of adult life: the soft, luxurious coats and scarves, the interesting muddy marks of huge shoes on the thick carpet when it’s been raining, the great big men who linger and talk with my mother and who smell—and even look—like cigars, and the pretty little basket that the men put change and sometimes dollar bills into.

When we finally get home, my mother and I shake ourselves out and imitate the men we’ve seen that day, strutting and braying until I get the hiccups from laughing, and then my mother makes me hot milk with honey in it so I can fall asleep.

My mother heaps scorn on the men who come to the club, but she heaps pity upon her sisters-in-law as if it could put out a raging fire before it consumes her heart, though it seems to add fuel instead. She argues their case over and over, taking first the prosecution then the defense. I understand this sort of weighing and measuring, the adjustments and bartering, very well. When I go to church with Mary Margaret, I pry my mind open so that God’s dragon breath will smelt the impurities from my thoughts and I will be in an advantageous position to ask that my mother be relieved of pain and live until I’m so old that I don’t care about a thing, even her death.

Her head is tilted back to keep the cucumber slices from slipping off her eyes. “More water, please,” she says, flapping her hand toward the electric kettle on the dresser. She huffs with pleasure as I add hot water to the basin, and I feel in my own feet the pain loosening its grip.

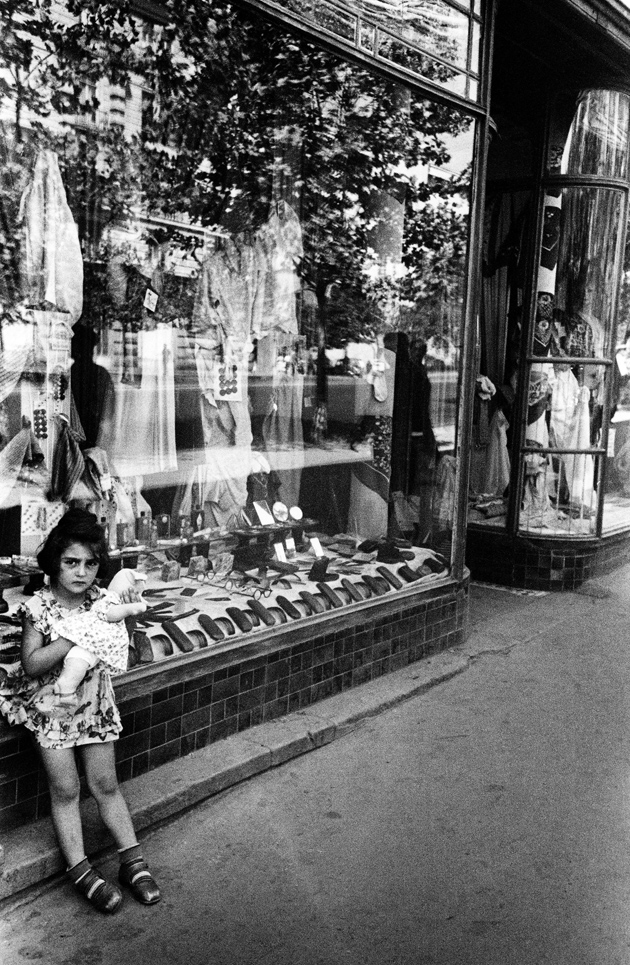

My aunts have undeniably beautiful legs—long, slender, and shapely. Showgirl legs, my mother says—incongruous, considering. She lifts the cucumber slices from her eyes and hoists herself up a bit to take stock of mine. I note with anxiety that the puffiness is not yet much reduced. “Good heavens—why are you wearing that thing?” she says. “Isn’t that the same dress you were wearing yesterday? It makes you look like an orphan!”

I hang my head. The dress is my favorite, a hand-me-down from Mary Margaret, who is big for her age as well as two years older but who spends time with me because, as she says, she lives next door. Or because, as my mother says, she’s limited. I have been wearing the dress all week. Its length and amplitude, in my opinion, cloak me in a penitential holiness, as though I were being led to the stake.

“I seem to remember that you were wearing it yesterday. Do I have to tell you again that’s not nice? Go change. And be sure your underwear is clean, too, in case you’re run over.”

My mother is generally attentive to detail—my shoes are to be polished, my hair braided so tightly sometimes it hurts, my nails scrubbed, my handkerchief fresh, the clothes in my closet pressed and hung up or folded neatly, my bed made with square corners—but she has spent the last few days in her darkened room with a wet cloth over her eyes, which accounts for the lapse concerning my dress. When she is stricken with a migraine or when the phone rings and she must work extra at the club, either I am to fix my own supper and breakfast, or else I am packed off to my aunts.

“Best behavior!” my mother orders. “It’s no easy thing, no matter what they say, to have a child underfoot, and I want you to make as little trouble for them as possible. No pestering, do not, under any circumstance, leave a ring around the tub, no prying, no personal questions, if your aunts offer you a gift, politely decline it—you have an unbecoming acquisitive streak and they can’t afford to throw money away on foolish extravagances; moreover, we do not want to be beholden to them. Try not to get the hiccups, they’re unattractive and could be interpreted as a bid for attention. Morrie has always been well- behaved, and the coven will be brewing up reasons to find fault with me.”

I protest—my aunts always say nice things about her, I tell my mother. “Hypocrites,” she says.

My aunts live at a convenient distance from us, close enough so that I can be parked with them whenever my mother is indisposed or out late into the night but far enough away so that we don’t run into them at every turn, as my mother puts it. My mother’s high standards in pastry, however, sometimes cause us and one or another of my aunts to collide at what my mother says is the only acceptable bakery—or patisserie, as my aunts call it—in our small city.

My mother keeps her back to the door as we sit at our table in the bakery, but when one of my aunts happens to enter, I jump up, elated by this demonstration of destiny. “Aunt Bernice!” I cry out.

“Hello, doll face,” says my aunt. My mother dispenses an icy smile toward which the impervious intruder returns a sweet, vague wave and I sit back down quietly, eyes lowered. My mother rewards me absently with a little pat.

“Affected,” my mother instructs me later. “Intolerably pretentious. Still, you have to be sorry for them. Their lives never amounted to anything, they’re too weak to fend for themselves, they have no resources of their own, and they don’t have the self-respect or drive to develop any. You’re timid and morbid yourself, so I hope you can at least feel some sympathy.” She looks sternly at me and I nod. “A bad habit, timidity. You have to learn to take the initiative and act decisively. But it’s no wonder those three are so helpless and wool-brained. The mother was a tyrant. Be glad she died before you were old enough to remember her. Patisserie! All you ever heard from that old witch was Petersburg, Vienna, Kraków. Petersburg, Vienna, Kraków, my hind end! They were smuggled out of some sewer in the Ukraine, the parents. They ate slops.”

Petersburg, I know, is Saint Petersburg, the place where people drank tea dispensed from the beautiful machine called a samovar, one of which I’ve marveled at in my aunts’ house. Aunt Adela inherited it, as she’s told me, from her own dear mother. “She brought that samovar all the way from Saint Petersburg. I don’t know how she did it, the way they had to travel, poor things—the wagons, the boats, the vicious border guards…”

I look at my aunt. Where to begin? “Yes, darling,” she says. “We mustn’t dwell on it, but we have to be grateful. We have to be grateful.”

The beloved item sits on a little marble-top table in the parlor, much the way the electric kettle sits on my mother’s dresser, similarly a comfort and reminder of her own ancestral home, Great Britain. “My poor father’s passage over…” my mother says once, bleary with painkillers, and she trails off, dabbing at a tear.

“To heaven?” I ask after a few moments.

“What?” she says.

“To heaven?” I ask again.

She sits up and looks at me. “What are you doing here?” she says. “It’s way past your bedtime.”

What mustn’t we dwell on? Well, everybody knows that, really: we mustn’t dwell on what came before. Schoolmates and teachers have always asked me, for example, what my father does. Does?

I myself know better than to go around asking annoying questions. My mother does not tolerate such questions for an instant, not one instant! And at school I feel perfectly entitled to answer questions of that sort as I see fit—my father has been a doctor in a leper colony, a bank robber, and a rodeo cowboy—which earns me a little reputation for unreliability. But by the time I’m nine or ten, I’ve learned to smooth over those awkward moments by just clamping my lips and walking off.

At my aunts’ house, though, I plant myself conspicuously in front of an old, pinkish-gray, framed photograph that hangs in the front stairwell. “Yes, darling,” Aunt Bernice says. “That’s our family. I’m the one on the left there, in the pinafore, and that’s your Aunt Charna with the big bow in her hair, and your Aunt Adela is in the lovely lace dress. Those are our dear parents, and the littlest one, in the sailor suit, is your father.” The six terrified-looking people dressed up in bizarre, old-fashioned clothing stare straight out, as if embarking on a perilous voyage. They all look exactly alike, including the little boy, my father.

“A samovar,” my mother says. “For god’s sake! I don’t know why they don’t sell that ruin of a house and all the vulgar old trash inside it and get themselves reasonable little places of their own where they could live independently, away from the spell of that harpy, and at least dust.”

The dust in my aunts’ house is the dust of transformations—a languid, floating gauze that becomes sparklingly apparent when the rare light comes in through the tall windows. The gilded armchairs in the parlor are upholstered in dark velvet so worn on the seat and arms that the white muslin shows beneath, a ghost poised to emerge from within a dying body. The immense Oriental rugs are worn almost white in places too, but as you study them the sleeping intricacies begin to surface in the weave.

When I am tired of drawing with the colored pencils I have brought, I mark off the hours, even the minutes, before I can return to my mother. The house is huge, and as many things as there are in it, it is still nearly empty. I go from room to room in the faint, gauzy sunlight, pausing to stare at some object or small piece of statuary until its transporting properties warm up. The ghosts flimmer in their chairs, the hieroglyphics rise up in the rugs, the stopped gilt clocks and cracked ornaments begin to pulse with the living current of their memories, and a few filmy pictures, too faded to see clearly—streetcars and cafés and people in heavy, old-fashioned clothing hurrying along in a cold, twilit city—peel off into the sparkling dust.

Sometimes, when Aunt Charna is away on a trip with a person who has asked me to call him Uncle Benny or a person who has asked me to call him Uncle Solly, I sneak into her room and lie spread-eagle on her red satin bedcover that looks like a rumpled sea of blood, staring up at some splotches on the ceiling, which are friendly or unfriendly, depending.

In the room where I sleep, there is a shallow fireplace. There are similar fireplaces in each of the bedrooms on the second and third floor—six in all. None of them work now, but Aunt Bernice says they all used to. Mine is the prettiest. The tiles are pinkish marble. Some of them are missing, and each blank patch where a tile is missing is like the blank patch left by a picture that shimmers for a moment in the transitional landscape of waking from a dream, and then is gone.

I stroke the patches where the tiles once were, close my door, and descend one of the lordly mahogany staircases that march up and down the house, all the way between the attics and a vast, green warren of subterranean areas, thick with whirring pipes, that I’ve peeked into from time to time before scurrying back up into the house again. On one quick reconnaissance mission I glimpse a strange, tall table, covered with something fuzzy, sort of like blotting paper, that has channels along its edges and round drains in the corners.

“Is Morrie coming home soon?” I ask my aunts over and over when I visit. “Soon, darling,” they say, but Morrie is always away, now, at the conservatory, because he is to have a great future. He no longer looks like an angel, and when he finally does come to visit, he spends most of his time practicing or playing duets with Aunt Bernice, though once in a while he can be persuaded to play cards with me.

“What is the fuzzy table in the basement for?” I ask him clandestinely, as he puts down yet another winning hand and rakes in yet another heap of matchsticks.

“The fuzzy table…” Morrie says. “The fuzzy table. Oh, yes. Billiards.” I search his face, but it’s as blank as any liar’s. “Billiards was a game that wealthy people used to play.”

“My other grandfather was rich,” I cannot refrain from announcing to my mother when I get home.

“Have you been communing with the dead?” she says.

“Morrie told me.”

“Well, Morrie’s never wrong, is he. Yes, your grandfather on that side came over dirt poor like all the rest of them, made a lot of money in textiles, and then he lost it all in the Great Depression. He was poor and then he was rich and then he was poor again just in time to die, and those girls are living in the crumbs and ashes.”

My mother says that when you hear Morrie play the violin you believe he really will have a great future, as an accountant.

One day my Aunt Bernice and my Aunt Adela bring me along on errands, and there in a shop window we’re passing is a fluffy pink sweater that looks like cotton candy, just my size. “That would be adorable on you with your red hair,” Aunt Bernice says, pausing.

On me? Joanie Hodnicki, the prettiest and meanest girl at school, has a similar sweater, but hers isn’t even as good as this one.

“Would you like to try it on, doll face?”

My head starts to throb. It’s true—I do have an acquisitive streak!

“Don’t you like it, darling?”

It is impossible to speak, or move.

My aunts look at each other helplessly.

I close my eyes, and feel myself sway as I imagine the delirious joy of squashing Joanie Hodnicki’s face in.

“It’s all right, darling,” Aunt Bernice says, “You don’t have to. Come along.” I catch them exchanging glances again.

But what can I say when Aunt Charna returns from a trip with Uncle Benny or Uncle Solly carrying a gift for me? Because she can’t just go back to where she was and return it! Once she brings me a big pad of delicious paper and some gorgeous crayon-like things, pastels, which I leave at the house for when I visit. And once she brings me a set of ten smooth, miniature square bottles filled with different colors of nail polish, lacquers, they’re called—Sun and Jade and Leaf and Ruby and Midnight and Ocean and Flame and Amethyst and Dawn and Moon—which I successfully hide from my mother.

But the very first thing Aunt Charna ever brings me, when I am very little, is a lovely baby doll. And when Aunt Adela deposits me back at home I rush to show my mother. “She blinks!” I say joyfully, waving the little card that came in the box with my new doll. “And she cries.”

My mother regards the doll dispassionately for a moment. How can she not be dazzled?

“And she can even wet herself!” I add, pleadingly.

“Really,” my mother says.

And so not only have I upset my mother, I have also humiliated a defenseless doll, who was given to me for safekeeping.

My aunts have their suppers in the kitchen unless Aunt Charna is there with Uncle Benny or Uncle Solly and we eat in the dining room. We sit with our broth amid the silvery clinking of our spoons against the chipped porcelain, and if I squint, I can almost see the terrified old witch in the family photograph—my own grandmother—at the head of the huge table, hunched noisily over a dish of slops.

There are two pianos in the parlor. I don’t play the piano. My lack of musical talent is impressive, my mother has informed me, and lessons would only be a waste of money. This is a shame, though, I explain solemnly to my aunts, who listen with raised eyebrows, because my mother says that those of us who will not necessarily be able to rely on our looks need to invest time and effort on cultivating our other assets. My aunts look at one another and then Aunt Charna puts her hands over her face and lies back, her lazy, round laugh rolling from her. My mother can be counted on to speak her mind, she says, and Aunt Bernice and Aunt Adela titter a bit, sadly.

Aunt Bernice plays a piece, making so much noise it sounds like she’s playing both pianos at once. I inspect an ornate gold clock that always says nine minutes after three and contemplate the wonderful samovar—teakettle, I think, severely—and before the piece finishes I still have all the time in the world to watch a sated moth stagger along on one of the silk curtains.

Sometimes I think I’ll go mad, my mother says about one thing or another. And sometimes I think I’ll go mad, from boredom—especially in my aunts’ empty house, with its murmur of indecipherable allusions. When I’m so bored that I don’t care whether I live or die, I go out in back and consider the ravine.

The ravine is a great, jagged cleft in the earth, so clogged with vines and poison ivy and fallen trees and trash that you wouldn’t know how to put a foot into it if you dared. Something lives down there now with fur and bright eyes.

“Do they put dead bodies in the ravine?” I ask Morrie on his visit home. “Who?” he says, with that blank face.

“Those are shamrocks,” Aunt Adela tells me as I peer at the happy little clovers on the teacup from which I’m drinking hot cocoa. “Shamrocks signify good luck in Ireland, where your mother’s father came from.” “Ireland?” I say, studying the shamrocks to affect indifference while a balloon of invisible information starts to fill up the room. “It was not Great Britain?”

“Ireland, Great Britain…” She shrugs. “I don’t know where his people were from or why they stopped in Ireland. But that red hair of yours and your mother’s probably came from Galicia, where her mother’s family came from.”

Galicia. I contemplate the beautiful name as it unfolds, disclosing delicate, prancing, caparisoned horses and the lovely princesses riding them whose undulating red hair reaches to the carpet of flowers beneath the hooves. “You could always tell the Jews from Galicia by their red hair,” my aunt says dreamily.

“Oh, dear! Did you burn yourself, doll face?” she cries, jumping herself, as my teacup shatters on the floor. “There, there, it’s nothing, it’s nothing.”

“Galicia!” my mother says when I’m back home again, pouncing upon my cautious, squirming hint. “Absolute nonsense! What have those ninnies been telling you? My mother was Hungarian. From somewhere near Budapest. Don’t stand there with your mouth open, you’ll swallow a fly. Budapest, the most sophisticated city in the world. Your grandmother was poor, but she was very beautiful and very refined. When she put down newspapers after she scrubbed the floor, she called them Polish carpets.”

But I have more pressing worries than having gotten my aunts in trouble. Because it has struck me that if Mary Margaret finds out that my aunts and my mother are Jewish and—I suspect—that maybe I consequently am, too, she might not let me come to church with her any longer. I am not exactly allowed to go to church with Mary Margaret anyhow, so I have perfected a careful course between lying to my mother and disobeying her, and I join Mary Margaret when her frame of mind and my opportunities align.

Edward Gorey Charitable Trust

Drawing by Edward Gorey for Rhoda Levine’s Three Ladies Beside the Sea, 1963; from a new edition published by the NYRB Children’s Collection. An exhibition of Gorey’s work, ‘Gorey Preserved,’ will be on view at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New York City, until July 27, 2012.

In any case, my mother’s main objections to my spending too much time with Mary Margaret seem to be that when he is not working his shift, her handsome father is often on the porch, drinking beer straight from the can, and that one of her many, much older brothers has been sent off to prison.

Still, it’s not too hard to sidle next door to Mary Margaret’s house, where nobody notices us especially amid all her relatives. And then sometimes Mary Margaret agrees to take me to church, though she won’t let me get up to take communion with her because I’m not in a state of grace. I’m afraid to ask why not. I can guess. It’s because I haven’t washed well enough. But even if I’ve washed and washed I don’t protest, because I am more afraid of violating a rule in the lofty, solemn place full of God’s echoes and perfume and fleeting colors than I am even of stepping on a crack in the sidewalk and breaking my mother’s back.

Whether or not to tell Mary Margaret has been weighing on me for some time before I conclude that it is necessary, for the sake of my soul and hers, no matter what the consequences. So, one day, after a wracking night, I hunt up Mary Margaret, to whisper my confession.

Mary Margaret whispers back: “I already knew it! My father calls you and your mother ‘the Jews’!”

“Are my mother and my aunts and my cousin and I going to go to hell? Cross your heart!”

We stare at each other in consternation, and then she nods. “But maybe if I bring you to church with me enough we can get your term reduced.”

I get Aunt Bernice to clarify whether or not Jews believe in God, and she tells me that yes, absolutely, we Jews certainly believe in God, although strictly speaking, she herself doesn’t and neither do Aunt Adela or Aunt Charna as far as she knows, though of course they all sometimes observe the high holy days together, and neither, she thinks, does my mother.

All right—so, you’re walking around in a cloud of facts that are visible only to others. This has become evident to me. Your eyes blink, like a doll’s, you can move your arms and legs, you can even cry or wet yourself, but you weren’t born like a doll in a box, with a little card that says things about you, and if you want to know how it is that you arrived on this planet of ours, you can’t just sit around blinking like a doll.

So, I begin to give detailed attention to my mother’s bedroom and rummage when she’s out. I find remarkably little of interest, except for a few ground-down lipsticks, a bottle, behind her shoes, the colorless contents of which I identify confidently, after a puzzled sniff, as whiskey, and small caches of money. These last have practical value at least, as Mary Margaret has been charging a small fee to take me to church with her, which seems reasonable enough now, considering.

I break into sweats whenever my mother emerges from her room frowning. But I am meticulous about covering my traces and circumspect in what I lift, and in time it becomes clear that she doesn’t keep careful track. The secret activity produces an irresistible physical thrill, better than the stupid slides and swings at the playground, which I’ve long outgrown, better than horror movies on television, better than poking a foot into the ravine at my aunts’ house to see if the mud will swallow my ankle and suck me down into the vines and poison ivy and animals and dead bodies.

But it’s as if my mother knows. Because, around the time I enter high school, I always turn out to be wrong. I have gotten a spot on my skirt, or my hair is a mess, or my posture is deplorable, or—my mother says—I’m glowering. Nor do I do enough around the house, and I refuse, in general, to take responsibility.

That’s true—but when I try to be useful, I wreck things! For instance, my mother has been distressed because the curtains are dingy and she can’t afford new ones, so one Saturday, while she is working, I take them to the laundromat for a surprise, and out of the machine comes a big wad of shredded rags.

I throw up, of course. And when my mother gets home and sees them, she turns white and then red and then white again. She makes a phone call, puts me in the car, drives me to my aunts’, reaches across me to open the car door, waits until I get out, and speeds off, without going in to say hello.

Aunt Bernice tactfully makes a pot of tea while I sit in the parlor, not crying—not crying—not crying even when she comes back with the tenderly painted little tray, the tea, the milk and sugar, and she sits down not too far from me.

We sip our tea for a few minutes, and then Aunt Bernice says vaguely, “She was a beautiful woman. She might have expected more from life. My brother was a very charming person, but not very forceful. No doubt they both expected something very different. Your mother has had disappointments. And, frankly, darling, I suspect that the change is hard for her.”

The change? Ah, yes. It’s a fact. I used to look different. A bit like my mother. But now all that’s left in me of her are my red hair and my unremarkable legs. Now I look like the other side of the family. I look like the little boy in the photograph, my father.

“Perhaps she feels it’s the end of her life as a woman,” my aunt says, gazing forlornly into her teacup.

All through the rest of the country, the rest of the world, people just a few years older than me are trying to learn to be kindly, rather than vicious, animals—letting their hair grow as long as it wants to grow, letting their clothes fall off, joining hands, considering matters of justice, hugging each other, smelling flowers, seeing visions. What clothes they do put on are brighter than any nation’s flag. In our small city, where darkness and cold go on and on, and most things smell and taste like lint, I groan with longing. The shadows of the freed young people flicker from the TV screen across my mother’s impassive face until she summarily stands up and clicks off the set.

One Saturday my mother and I go to the bakery for a treat, and we sit at our favorite table. I am a bit smeary from eating my éclair with my hands, which is amusing my mother not one bit, and in walks Brucie Miller with his brother, Preston. “Hey, hi,” Brucie says vaguely to me.

My hand is paralyzed in its reach for a napkin. “Oh, hi,” I say, and look at the walls and the ceiling.

When we get home, my mother sits me down in the living room, which always means trouble. Why now? Did she see Mary Margaret sashay by in that tiny new skirt of hers?

“There’s something we have to talk about,” my mother says, and closes her eyes for a moment. “Pretty girls are not to be envied. Because when a boy sees a pretty girl, he does not see a real person. He sees a mirror of his own desires, and he falls in love with the mirror. Boys put a pretty girl on a pedestal. Do you know what I mean by that, ‘on a pedestal’?”

“Obviously,” I say.

“No need for truculence. A boy will do anything to get the attention and admiration of a pretty girl, and then he courts and pursues her, and when she finally falls in love with him, he understands that she is not a mirror, and he runs as fast as he can. But girls who are not pretty are in an even worse situation. Boys believe that girls who are not pretty have only been put on earth as a poor compensation for what all boys believe the world owes them.”

A hazy, swimming rectangle, filled like a battlefield with a distant clangor, inflates between me and my mother, though her large, staring face floats right in front of my eyes. Sweat begins to film my upper lip and under my arms, and I squeeze my clammy hands together as I hear my mother saying, “Boys know that girls who are not pretty are desperate for attention, and they congratulate themselves on the fact that those girls will do anything at all for what they can pretend to themselves is affection. So when a boy tells a girl who is not pretty that she is pretty or that he cares about her, she can make a fool of herself or not, as she chooses, but she believes him at her peril.” And I am just about to be dissolved, when I feel my aunts, with their strange, aliens’ faces, which mine has come to resemble, marshal all their strength to cluster in the air behind me, a little phalanx facing my mother too, and I take a deep breath.

“What do you mean?” I say.

“That’s what I mean,” she says.

“What?”

“That. What I said.” She gets up and goes into her room, closing the door loudly behind her.

“You must have wanted to get caught going through her things,” Jake said to me many years later, when, in our early elation over the miracle that all the elements of the universe—a web of happenstance beyond calculation—had brought us together, we were tremulously passing back and forth to one another our biographies, containing all their apparently random data, as if they were precious archaeological trophies that would sooner or later yield up, from some overlooked fold or crevice, an explanation, a credible excuse, a key.

Maybe I did want to get caught—you could certainly make an argument for that, of the shallow psychological sort that generally contains some shred of accuracy—or maybe I did not. But in any event, I did get caught in her room going through a drawer, and by the time I did and the inevitable annihilating explosion occurred, I was sixteen and just out of high school and had grown far removed from Mary Margaret and God and any desire for salvation, and the money I had filched from my mother over the years and hoarded was enough, amplified by hitchhiking, to take me nearly a thousand miles away, though no distance at all could be put between me and the unmistakable signifier of my weakness and cowardice, my pitiful, leechlike dependency on the lifeblood of others, my congenital inadequacy: “I should have known that you were one of them,” my mother said, “as soon as I saw that you were getting their nose.”

It was owing to Jake that I eventually got work illustrating medical texts and that I studied enough biology and anatomy to be able to do so at all. When we met, I was taking a graduate degree in graphic art and working in bars and restaurants of various types. Since the time I arrived in New York I’d been a fry cook and a line cook and a waitress and a prep chef, and at the end of my shifts, my overtaxed feet would swell with venom, which I would sometimes try to soak out.

But the night I met Jake I was tending bar at a place popular with young, stoned, Wall Street high rollers. It was a good and lucrative job, the best I’d ever had. The person who turned out to be Jake was sitting at the end of the bar under a feeble light, trying to read. He put a fifty down in front of him, and I poured him a draft and forgot all about him. My attention was on one of the regulars, whom I thought of, with loathing, as Mr. Perfect.

Mr. Perfect was the idol of our manager, Nelson, and he almost never came in without a shockingly gorgeous girl, rarely the same one twice. They would sit down at the bar, Mr. Perfect and the girl, and the predictable theatrics would start right up, so the moment he appeared I’d resign myself to a night of watching a wallet flirt with a price tag.

Mr. Perfect always ordered their drinks and awaited them and then criticized them a bit with a warm, genial manner as he suavely basked in the sunshine of his own power and his date’s gorgeousness, a display, obviously, intended for an audience. When the smugness index could go no higher, Mr. Perfect and his date would slip off their barstools and slide toward the door, merging as they went, leaving the rest of us adrift in their gamey hormonal wake to face our empty lives.

It was not Jake’s presence in particular on that night that unmuzzled me, though it pleased him to think so, of course. But, possibly, had there been no witness to my degradation, no personable man reading at the end of the bar, I might have made it through the shift without opening my mouth.

In any case, I happened to be mixing a martini for Mr. Perfect’s date, as, right in front of me, Mr. Perfect was gazing into her eyes and scrounging under her sweater. “I’m sorry,” he was saying, “but she leaves the mail in a mess to show that she’s been working on it, she can’t make a decent cup of coffee, she bites her nails disgustingly, she’s awkward on the phone with clients, and this morning she actually put a call through when I was in a meeting with Rutherford.” “You’re such a perfectionist!” the date said. “I hate being a perfectionist,” he said. “It’s a character flaw, but I am a perfectionist so I had to fire her.”

“Well, but maybe you didn’t have to fire her because you’re a perfectionist,” I suggested, “maybe you had to fire her because you’re an asshole.”

The warm and genial expression emptied from Mr. Perfect’s face. It was the first time he had ever actually looked at me. “And you’re fired, too,” he said.

“You can’t fire me,” I said.

“I can fire you,” said Nelson, unfolding out of some dimness. “You’re fired, will you get out of here?”

“Gladly,” I said, tossing my bar rag down as I extracted myself from behind the bar.

The guy at the end of the bar had looked up from his book and was staring in my direction with a love-struck expression. I glanced over my shoulder, but no one was standing behind me. I glanced back at him. “You—” he said. “You, will you go somewhere else and have a drink with me?”

“I’m filthy,” I said. “Are you kidding? I’m disgusting. I’m covered with grease and brine. I’m sweating.”

“So, will you go have a drink with me?” he said.

“No,” I said. “I’m filthy.”

“Well, so will you go take a bath with me?” he said.

Over the years, it has dawned on me that people who have an immediate and deep response to one another also have an immediate and deep inkling of the dangers in store, and express significant warnings to one another that they then instantly forget for a very long time. “Look, I don’t enjoy being an out-of-control furious maniac,” I said. “If you think this is fun, that’s a problem!”

“You won’t be an out-of-control furious maniac if you hang out with me,” he said. “I’ll make you happy!”

“That’s sort of an enraging thing to say,” I said.

“Will you please get out of here!” Nelson said.

“Right away, boss,” I said.

“Wait—” Jake said. He grabbed the fifty he had put on the bar and produced a pen from his pocket. “Give me your number!”

In my confusion I hurriedly wrote my number on the fifty, then tried to snatch it away from him. “Hey, you’re just going to spend that, and every ax murderer in town will be calling me.”

Jake tore the bill in two and handed me the half without my number. “I’m broke,” he said. “I’m a grad student. Have pity. I’ll tape it up when we see each other and we’ll go spend it on a movie!”

“Will you get the fuck out of here now!” Nelson said.

“You don’t have to ask me twice!” I said, and slammed out the door.

Really, I believed that I had put my mother mostly out of my head during those years. But late one night, a little tipsy and with great trepidation, I called my childhood phone number. To my shock, the voice that answered was my mother’s, and I realized that I had been waiting all that time to assemble a file of unimpeachable credentials before I contacted her. So pathetic. I might as well have been bringing a mauled mouse to my owner’s door.

“You might have thought about me,” she said. “You might have thought about the worry. I was sick with worry about you. I didn’t even know if you were alive until Morrie told me he had heard from you, a year or two ago. It nearly killed me.”

“I’m very sorry,” I said evenly—though so intense was the flood of vengeful triumph engulfing me that later I couldn’t remember how I came to find myself on the floor after I hung up the phone, though a few bruises suggested that I had simply lost consciousness for a moment and clonked myself against a table on the way down—“but you did say that you despised me, that I was a worthless waste of your life, that I was personally repulsive, whatever you meant by that—”

“Now, how could I ever have said anything like—”

“—that you knew the minute I was born that you should have given me to some poor stooge for adoption, that I smelled, that you never wanted to see me again, that you would have traded me for Morrie and a bag of compost any day—that sort of thing.”

“I was disappointed in you,” she said. “I said things I didn’t necessarily mean.”

“Ah, well, then,” I said.

“After all, you were no picnic. Are you in trouble?”

“Do you mean am I pregnant?”

“Well?” she said.

I was not pregnant, I told her. Nor was I in trouble of any kind. I had only called to tell her that, on the contrary, I was very well. I did not mention, of course, that I had graduated merely cum laude but I did let it be understood that I had done well enough at a respected college (not one she respected, as it turned out) and had gone on to acquire a graduate degree, and that I was with a person she could hardly sniff at, someone who did work with deadly pathogens.

“‘With?’” she said. “A person?” I heard her sit down abruptly.

Not to worry, as it happened the person I was with was a man, a very nice, flawlessly presentable man. A man who had stood by me, a man who had a high opinion of my abilities and character, a man who, in fact, actually liked—

“And is this paragon a doctor?”

I hesitated. “A researcher.”

“I see. A researcher. And how long have you been with this researcher?”

“How long have we been living together?” I said. “A few years.”

“Living together!” she said. “Is that how I brought you up?”

Most of my intimate involvements had lasted from about midnight to about 2 AM, as my mother might have expected of someone not on a pedestal, but the span of this particular liaison, with which I had intended to impress her, had obviously had the opposite effect, and after all this time I was still not equipped to endure her opprobrium. “Well,” I said cheerfully, “‘Marry in haste, repent at leisure.’”

She started to chortle but collected herself.

After that call, we spoke from time to time, cautiously. And then one afternoon she called to say that Aunt Bernice had died and as she’d expended so much effort on me she probably would have liked to know that I’d at least be willing to take a day off from all my important business to fly out and attend her funeral.

Jake insisted on coming with me, and as we entered the funeral home, I noticed that my grip on his arm was probably painful. Several shabby-looking old people were huddled together as if it were sleeting. Slowly it came to me that they were Aunt Adela, Aunt Charna, Uncle Benny, and my mother.

My shrunken and frail mother detached herself from the group and was walking toward me with great difficulty. “It’s all right to cry,” Jake said, putting his arm around me. “Go ahead and cry.” “Fuck you,” I yelped, and wiped my eyes and nose on my sleeve. My mother and I sort of made as if to hug, but slipped off each other. “Mother, Jake,” I was trying to say.

“Jake,” she said, holding out her hands to him and radiating dewily like a young and beautiful woman, “Thank you for taking such good care of my poor little girl.”

“Excuse me?” I said, but they were embracing.

“Where’s Morrie?” I asked.

“Tokyo,” my mother said. “A concert, according to Adela. ‘Impossible to cancel’ if you please.”

My mother had become quite hard of hearing. “This one’s a mumbler, too,” she said with distaste as the rabbi started the eulogy. “What’s he saying?”

“That she was an exemplary person whom we all loved and looked up to very much.”

“By God,” my mother said loudly, “they’re burying the wrong woman!”

Some years earlier I had tracked down Morrie’s address—he was already famous—and I wrote him a letter. He organized it into questions, to which he responded with a numbered list:

1. According to records, our common grandmother 4 siblings, all stayed in Europe: 1 Auschwitz, 1 infant diphtheria, 2 Treblinka. Our common grandfather 7 siblings, all stayed in Europe: 1 Majdanek, 1 Chelmo, 1 unknown, 4 Auschwitz. My mother and your father 13 cousins: 2 Treblinka, 3 Auschwitz, 4 unknown, 4 Sobibor. You and I at least 5 cousins, all b. 1930–1944, all (known) Auschwitz. No known family survivors except our common grandparents. All four of our grandparents’ parents, Auschwitz.

2. Grandfather probably Belarus or Lithuania. Grandmother Romania or the Ukraine. Nationalities depend on year in question, as borders fluctuated rapidly 19th and early 20th centuries. Primary language in any case Yiddish, which, no nationality.

3. Your father (my Uncle Joseph) went missing the month before your birth. Attempts to trace him unsuccessful.

Morrie went on to say that it was very good to hear from me, that his mother and her sisters always spoke of me with affection and hope, and that he had fond memories of playing cards with me when I was a child and once taking me to a movie about extraterrestrials that seemed to make a big impression on me.

After the funeral service, there was a little reception at my aunt’s house. My mother was sitting alone at one of the little marble-top tables, sipping something. She was staring straight ahead, her face devoid of expression, as if she were dreaming the house and everyone in it, the subdued hubbub around her, her life. It struck me that I myself would be old before too long. I hesitated, but remained standing and then went over to say a few words to Aunt Charna and Uncle Benny.

“I expected something immense,” Jake said, gazing around the parlor. “It’s not really all that big.”

Was it possible that he was actually a bit dim? “I was smaller back then,” I said, with fastidious patience.

It looked miniaturized to me, too, of course, and only seconds from shuddering into splinters. But it had almost finished serving its purpose, anyhow. In the following few years, Charna died, and then Adela, and then my mother. And now that Morrie is not around to remember them, my aunts may finally be released from the house—the elegiac murmuring of the carpets and chairs and billiards table and clocks, the unquiet sleep hovering over it, bringing dreams of the planet my grandparents came from, with its blood-stained ghetto walls, the pistol butts beating at the doors, its rhapsodic festivals of murder. Will I finally miss them, my aunts? I sit up on the couch, a bit drunkenly, to take note. Yes, off they go, my old allies, sailing right through the harsh, radiant shield at the edge of the universe, blending into darkness.

My mother invited us to stay with her the night after Bernice’s funeral. Out of the question, of course, but Jake gallantly escorted her to her house, and when he got back to the hotel where we’d booked a room, he hugged me as if he’d just had an invigorating adventure. “Whatever else, your mother certainly has a lot of charm,” he said.

“Charm?” I said. “What did she say to you? That she was grateful to you? For getting me on my feet? For improving my character? For staying with me despite—”

“Look, I know this is painful. I know that it’s easier just to give over to resentment and to simplify the past by demonizing your mother rather than leaving yourself open to the stress of complex and ambiguous emotions. But you’re an adult now. Your life is your own. Why not accept what a difficult life she had, and leave that all behind. Because even though it was necessary for you at one time, and gratifying, by now this resentment is obsolete, and it’s just stunting you.”

I got myself a separate room for the night, and after I called my mother in the morning to say goodbye, I met up with Jake for breakfast and I couldn’t help mentioning to him that she had wished me better luck with him at least than she’d had with my father and said that he seemed like a decent man but a bit self-important, overly susceptible to flattery, and maybe not all that bright.

He took a quick breath in, and of course I was very, very ashamed of myself. “Your mother is as mean as a mace,” he said.

“She’s had a difficult life,” I was evidently not too ashamed to say.

When we finally got back home that night after being snowed in at the airport for hours, dealing with a ruptured carry-on bag, and sitting next to a sick baby in the lap of a sick mother who wore earphones that leaked tinny squawking during the whole flight, we had a long quarrel about the properties of vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which was something, frankly, Jake knew a lot more about than I did. By the time we’d used that up, we were completely exhausted, and we decided to take a couple of weeks off from our jobs to relax and get away from winter and just be together on our own.

And it was pure bliss, that holiday. One day, sitting in a nimbus of jasmine and orange blossoms in the gardens of an ancient palace while jaded-looking peacocks sauntered by, we considered the centuries of the kings and queens who had lived there and what it must have cost them to maintain so voluptuous and serene a refuge—the tyranny, oppression, and carnage entailed. But whatever the wars and lootings, they were long over, remembered by most of us, if at all, as a great number of names and dates that were easy to mix up. And real as all those events had been, all that remained were the palace with its reflecting pools and galleries and gardens and peacocks, the carefree tourists like us, and of course the invisible consequences that would keep spooling out through eternity. I tilted my face up to receive the sun.

“What were you looking for in your mother’s room?” Jake asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Nothing in particular.”

“But, really—what were you looking for?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Maybe a letter. A letter from my father, explaining why he had left. A love letter of sorts, I suppose.”

“And what would the letter have said?” Jake asked.

He took my hand with such sweetness. I think I blushed, actually. Looking back, I suppose the future—its chilly plan for us—had cast a fleeting shadow over him and he was searching for what I would need him to say to me when the time came. But back then in that fragrant garden, I was aware only of the light coursing between our clasped hands and the sun’s warmth on my face, with night idling where it was, half a world away.