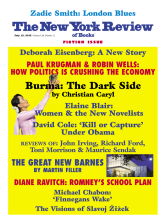

Michael Moran/OTTO

The Main Room of the new Barnes Foundation gallery in Philadelphia, designed by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien to allow for the collection to be arranged exactly as it was in its original Lower Merion location. On the far wall, Seurat’s Poseuses hangs above Cézanne’s The Card Players; along the top of the wall at left is Matisse’s mural The Dance.

1.

Nothing less than a latter-day miracle—a wholly unexpected and an unbelievably lucky one at that—has occurred in Philadelphia, where the most acrimonious and protracted power struggle in the recent history of art collecting has finally come to a glorious and uplifting conclusion. The opening this spring of the long-anticipated new gallery of the Barnes Foundation Collection, the finest concentration of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting in the Western Hemisphere, has been a triumph for all concerned. The combined talents of the New York–based husband-and-wife architectural team of Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, their senior associate Philip Ryan, and the landscape architect Laurie Olin have resulted in a wholly sympathetic and virtually unimprovable setting for a superabundance of treasures by such modern masters as Cézanne, Van Gogh, Seurat, Matisse, and Picasso, miscellaneous Old Masters, and many unnamed African tribal artists.

How such a fortuitous outcome could have emerged from a tortuous tangle of circumstances unequaled in the annals of modern art is a question that will surely fascinate analysts of the museum industry for years to come. But there is no doubt about who the big winner is: the general public, which now can enjoy unprecedented access to a peerless cultural patrimony long fettered by restrictions imposed by the high-minded, visionary, yet maniacally controlling Albert Coombs Barnes (1872–1951).

Barnes’s fierce determination to manipulate his enviable legacy from beyond the grave nearly caused his beloved possessions to be sold off by his designated legatee, Lincoln University, a traditionally black college in southeastern Pennsylvania, to which he left stewardship of his foundation, many believed, as a rebuke to the Philadelphia elite that had long snubbed him. As one cultivated doyen of Philadelphia high society dryly remarked years later of this self-made pharmaceutical tycoon and perpetually embittered outsider, “Perhaps we ought to have invited Barnes to our parties.”

Thanks to a coalition of concerned institutions and individuals that banded together early in the new millennium—including the Pew Charitable Trust, the Annenberg and Lenfest foundations, along with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Getty, Luce, and Mellon foundations, among others, as well as numerous private benefactors—the impending dissolution of this stupendous hoard was staved off and a huge cultural calamity thereby averted. A malign and melodramatic documentary film opposed to the new Barnes, Don Argott’s The Art of the Steal (2009), attempted to portray the institution’s relocation to Philadelphia’s Museum Mile from its original home in the Main Line suburb of Lower Merion as an act of naked thievery. But this civic rescue mission was actually comparable to a desperate family’s intervention aimed at saving a shared inheritance from being irrevocably squandered by an incompetent, out-of-control relative.

The saga’s tumultuous backstory, reported by John Anderson in his Art Held Hostage: The Battle Over the Barnes Collection,

1 makes it obvious who the real villains and heroes were, and for once the good guys won. To summarize briefly, Barnes’s overly conservative investment directives reduced his foundation’s solvency by the inflationary 1970s. As the value of his art soared exponentially—in inverse proportion to the shrinking endowment—the Barnes’s resources were further diminished by a costly lawsuit over a proposed parking lot on its property in an upper-class residential neighborhood opposed by local residents, and sapped through extravagant spending by some of its officials.

Although substantial funds were realized during the 1990s through a major book deal and a lucrative international tour of the collection while the gallery building was being restored, the Barnes was effectively bankrupt by the turn of the millennium. In 2002 the beleaguered Barnes board petitioned a court to let them break Albert Barnes’s trust indenture and move his art to the center of Philadelphia in order to make it more convenient to the general public—admission had been by appointment only and was severely limited—and thereby alleviate the institution’s fiscal crisis. Barnes had insisted that none of his eight hundred paintings or thousands of other objects could ever be sold, loaned, or removed from the elaborate installations he contrived for them. Thus, though the court agreed to the relocation, it stipulated that the collector’s displays be strictly maintained in the institution’s new home.

2.

Barnes, whose father labored in a Philadelphia slaughterhouse, put himself through the University of Pennsylvania and earned a medical degree, but saw greater financial potential in manufacturing medicines. He teamed up with a more technically adept colleague who devised the formula for an eyewash that prevented congenital gonorrheal infections in newborns. A skillful marketer, Barnes bought out his partner and made a fortune from the soon-ubiquitous solution, which he named Argyrol. The elder Barnes was a friend of Peter Widener, a fellow abattoir worker who later became a trolley magnate and an important art patron. Widener’s example likely inspired the younger Barnes to assemble his own, far more significant collection once the big money began to roll in.

Advertisement

In 1912 Barnes asked an old high school classmate, the artist William Glackens, to buy paintings for him in Europe, and his friend’s selection of choice works by Cézanne, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Picasso set the tone for the collection. Starting with Glackens’s choices, Barnes, relying on his own formidable artistic judgment, went on to build a collection of forty-six Picassos, fifty-nine Matisses, sixty-nine Cézannes, and 181 Renoirs, as well as Old Master pictures by Hans Baldung Grien, Tintoretto, Veronese, El Greco, Frans Hals, Salomon van Ruysdael, Claude Lorraine, and Goya, along with modernist works by Courbet, Daumier, Degas, Manet, Monet, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, the Douanier Rousseau, Redon, Braque, Modigliani, Utrillo, de Chirico, Soutine, Klee, Miró, and the Americans Maurice Prendergast, Charles Demuth, Glackens, Marsden Hartley, and Horace Pippin.

To house them, in 1922 Barnes engaged the Beaux-Arts architect Paul Philippe Cret (now best remembered as Louis Kahn’s teacher at the University of Pennsylvania) to build an imposing limestone-clad mansion in Lower Merion, a township bordering Philadelphia to the northwest. There he intermingled his pictures in galleries further crowded with Pennsylvania German painted furniture, Native and Early American pottery, Navajo jewelry, Greek antiquities, classical Chinese sculpture, and any other rare and beautiful objects that caught his all-encompassing eye.

Certainly the oddest component of these eclectic ensembles was the array of metal hardware and utensils he hung all around his paintings like nimbuses emanating from saints—curlicues of antique wrought iron that often echo sinuous linear elements in canvases or decorative objects near them. Detached from their functional setting, these finely crafted door knockers, escutcheons, hinges, keys, ladles, latches, padlocks, and other implements serve as calligraphic glosses on the pictures they surround. An even more effective display element is the ochre-colored burlap Barnes specified for the gallery walls, a color so harmonious with most of his pictures that one wonders why it is not widely copied elsewhere.

Another controversial aspect of the installation was his practice of “skying” pictures in tiers two or three rows high, a vertical arrangement traditionally employed by the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the Royal Academy in London for their annual exhibitions. Yet the Barnes galleries are so well proportioned and the pictures so intelligently disposed that there is almost never any difficulty in seeing even things positioned high on the walls.

Certain pictures, the Cézannes in particular, are strong enough to be read without difficulty across a large room even when hung eight feet up, as his Large Bathers is. The only serious exception is Seurat’s Poseuses, a tableau of artist’s models that possesses the transcendent equilibrium of a Botticelli. In an instance of complete aesthetic overkill, Barnes placed that shimmering Pointillist apparition, which begs to be seen at close range as well as from a further remove, over Cézanne’s somewhat smaller but monumental The Card Players. (Barnes officials are contemplating the periodic use of a forklift to allow visitors to view the Poseuses at eye level.)

On occasion, Barnes’s juxtapositions, all of which are maintained in the new museum, can be breathtaking. For example, in Room 22, on the second floor, the face-off between two ferocious Picasso oil studies of African-mask-like heads (1907), contemporary with his revolutionary Demoiselles d’Avignon, sets up a reciprocal magnetism further intensified by three late Medieval figures of the crucified Christ hung between these small but terrifying pictures. Barnes may have been a crank, but he was also touched with some kind of genius.

That appears especially clear now that visitors can see these fabled works better than at any time since Barnes bought them. The collector, fretful that light might harm his treasures, kept the Lower Merion galleries immersed in a depressingly subfusc gloom. Thus the most welcome aspect of the new Barnes is the veritable visual resurrection occasioned by the lighting designer Paul Marantz’s exquisite calibration and mixture of natural and artificial illumination—only two of the twenty-three display rooms do not have some daylighting—which has made even those well acquainted with the collection wonder if the works were cleaned as part of the reinstallation, though they were not. Perhaps the luckiest beneficiary of this transformation is Matisse’s tripartite mural The Dance (1932–1933), which Barnes commissioned for the lunettes just below the ceiling of the triple-height Main Room. This jazzy composition has always fairly vibrated with kinetic energy, but now its plummy colors strut their stuff, too.

Advertisement

In The Barnes Foundation: Masterworks, the new official guidebook, two Barnes curators, Judith F. Dolkart and Martha Lucy, as well as the museum’s director, Derek Gillman, capture the central qualities of the collection. However, this commendable survey does not supersede Great French Paintings from the Barnes Foundation: Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Early Modern,2 the first publication to reproduce these works in color (which Barnes had prohibited because he believed that his pictures’ true tonalities would inevitably be misrepresented). The earlier volume is further preferable for the art historian Joseph J. Rishel’s entries on Cézanne, which include some of the finest writing on that artist by any scholar, including the brilliant Meyer Schapiro, who Barnes spitefully barred from Lower Merion while he let Cub Scout packs and the odd working Joe roam the galleries.

Also newly issued is Martha Lucy and John House’s Renoir in the Barnes Collection, the initial volume in a projected series of catalogues raisonnés on the artists whose work Barnes acquired in greatest depth. It is regrettable that this is the first installment to appear, in that Barnes’s Renoirs—the one instance when his superlative eye failed him—are his collection’s weakest link. His taste tended toward the artist’s excruciating late female nudes, grotesque creatures with puny craniums and colossal bottoms—wobbly orange-tinted images of flesh so bloated that they seem eerily prophetic of our country’s current pandemic of morbid obesity.

3.

The design for the new Barnes emerged through an invitational competition organized by Martha Thorne, executive director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Portfolios were solicited from some thirty firms, and the selection committee, which included Barnes trustees and representatives of institutions backing the move, evaluated a well-chosen shortlist of six finalists: Tadao Ando, Thom Mayne of Morphosis, and Rafael Moneo (all Pritzker Prize winners), as well as Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Kengo Kuma, and Williams and Tsien.

The latter’s powerful little drawing, titled “Gallery in a Garden, Garden in a Gallery” (also the subtitle for their absorbing first-person account of the design process, with an essay by the architectural historian Kenneth Frampton), depicts an oblong ensemble of the same approximate outlines as Cret’s Barnes. Williams and Tsien’s proposal was likewise centered amid a landscape reminiscent of the original building’s graceful arboretum, with the addition of a small garden within a two-story-high glass-enclosed cloister inserted into the heart of the gallery wing in place of a light well in the Cret original. (That building is being retained by the foundation for horticultural programs.)

The exterior of the new Barnes is as well considered as the site planning, and both are perfectly enhanced by the elegant and appropriately Gallic landscape design by Laurie Olin, which features ranks of low hedges, allées of specimen trees, serene reflecting pools, and pathways of terre pisée—rammed earth. The long elevation of the building is set parallel to the north side of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway of 1917, the broad tree-lined boulevard that the French urban planner and architect Jacques Gréber sliced at a diagonal into William Penn’s symmetrical grid plan of 1683, a fanciful bid to give the staid Quaker City some Parisian élan. This outburst of Francomania was also responsible for Cret and Gréber’s jewel-like Rodin Museum of 1926–1929, directly northwest of the Barnes, devoted to the foremost modern French sculptor.

The new $150 million structure is surfaced in pale beige Negev sandstone, which harmonizes beautifully with the limestone-clad Rodin next door. Williams and Tsien’s handling of the masonry is ravishing. They deployed large rectangles of the tawny material in rhythmic patterns reminiscent of the geometric Kente cloth motifs woven by the Asante and Ewe peoples of West Africa, and interspersed the stone with thin, straight-edged, hammered-bronze “fins” that protrude slightly beyond the wall plane. This subtle detailing creates intriguing shadow patterns and alludes obliquely to the artisanal metalwork hung in the galleries within. This likeness to tribal textiles is most fitting, given Albert Barnes’s determination to accord African tribal objects the same status as European art, and his deep interest in African-American culture. Beyond that specific reference, the exterior stonework is a compositional masterstroke, for the architects’ division of the cladding into three huge horizontal bands at once brings the structure down to human proportions while at the same time giving it a civic monumentality.

One’s first view of the Barnes is reminiscent of the approach to Cret’s Folger Shakespeare Library of 1929–1932 in Washington, D.C., which is sited similarly, shares the same approximate dimensions, and is likewise masonry-clad but lacks the columns, balustrades, rounded pediments, and other traditional detailing of the slightly earlier Lower Merion gallery. The close resemblance of Barnes I and Barnes II is of course not surprising given the legal requirement that the new building follow the internal layout of the old structure exactly. That condition—which fortunately did not extend to replicating the original building’s Neoclassical exterior—meant that Williams and Tsien also had to retain the arrangement of windows and doors dictated by the rooms within.

This has been all to the good, because the faultless proportions characteristic of the Classical tradition were scrupulously observed by Cret, whose oeuvre evolved from the conventional Beaux-Arts proprieties of Barnes I to the more modern Stripped Classicism of the Folger. The interconnected architectural history of the first and second homes of the collection is well laid out by the University of Pennsylvania professor David B. Brownlee in his brisk but thorough account, The Barnes Foundation: Two Buildings, One Mission.

Apart from their superscale handling of the exterior stonework, Williams and Tsien’s boldest conceptual gambit was to surmount the 93,000-square-foot Barnes with a gigantic horizontal superstructure they call the Light Box: an immense translucent white-glass bar that dramatically cantilevers forty feet beyond the building’s north end and sixty feet beyond the south end. When illuminated from within at night, the Light Box serves as a wordless marquee that announces this singular new presence and imparts a boldly contemporary quality that makes it apparent, even from afar, that the new Barnes is not some gorgeously preserved cultural corpse laid out for solemn visitation.

The full impact of the capacious Light Court beneath the Light Box—an internal plaza that measures 170 feet long, forty-five feet wide, and fifty-two feet high at its apex—is felt with particular force as one exits the gallery wing. After the at times claustrophobic impact of Barnes’s jam-packed installations, you experience an astonishing whoosh of open space that comes as a liberating relief.

To the rear of the site the architects placed a reverse-L-shaped office-and-temporary-exhibition wing, parallel to and touching the gallery structure, between which the Light Court serves as a central gathering space. Entry to the Barnes is by advance ticket sale only and timed to a maximum of 125 visitors per hour, with a total of 250 allowed in the galleries at any one time. Educational services, including a lending library, an auditorium, and classrooms to accommodate the art-appreciation lessons Barnes so passionately believed in—he was a follower and friend of the philosopher John Dewey, whose pragmatism informed his ideas about culture in a democracy—are housed in a subterranean story.

The legal requirement to reproduce the old galleries made many observers fear that this would limit the designers to an exercise in cultural taxidermy, with little scope left for architectural originality. Remarkably, Williams and Tsien found unexpected expressive range within the confines they were bound to observe. In that respect the outcome of this project is dazzling—the new Barnes is infinitely superior to the vast number of museums designed with a completely free hand, and in hindsight, Judge Stanley R. Ott’s 2004 ruling that the display must be exactly duplicated seems Solomonic in its wisdom.

4.

Williams and Tsien are among several first-rank husband-and-wife architectural teams to emerge in the generation that followed such pioneering coprofessional couples as Alison and Peter Smithson and Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Tod Culpan Williams was born in 1943 to a well-to-do WASP family in Michigan—his father, an automotive engineer, invented the electrically controlled seat-adjustment device—and graduated from the private Cranbrook School (part of Eliel Saarinen’s celebrated campus of 1926–1943 in the Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills) four years before Mitt Romney. He went on to study architecture at Princeton, and after an apprenticeship with the neo-Corbusian Richard Meier, he set up his own Manhattan office in 1974.

Billie Tsien was born in 1949 in Ithaca, New York, to Chinese-American parents; her father was an electrical engineer, her mother a biochemist. She received degrees in fine arts at Yale and architecture at UCLA, and joined Williams’s firm in 1977. They married six years later, officially became professional partners in 1986, and have one son, Kai Tsien Williams,, an industrial designer.

Apart from their extraordinary individual talents and complementary balance of design skills—he concentrates on structural aspects, she attends to materials and finishes, though neither exclusively—Williams and Tsien stand out among their contemporaries for a determination to keep their staff small enough to maintain the hands-on control they deem essential to an art-based practice. Their firm generally takes on only two new assignments each year, has never had more than forty employees, and currently numbers around twenty.

As a result, their output has been relatively small: twenty-seven institutional buildings completed thus far, and seven houses. Unlike several Pritzker Prize winners, they have never designed one of those increasingly common retail showplaces exploited as signature “branding” by international luxury-goods conglomerates. They prefer to work solely for educational and cultural institutions, following the example of Kahn, who likewise sidestepped involvement with corporations.

Among Williams and Tsien’s best designs is the Williams Natatorium of 1998–1999 at Cranbrook, which his family gave to his high school alma mater. Because Eliel Saarinen’s vision for the campus was so comprehensive, it has been very hard for other architects to add to his minutely coordinated ensemble. Far and away the most successful post-Saarinen structure there is this majestic indoor swimming-pool hall, which numbers among the handsomest sports facilities of recent decades.

Williams and Tsien evoke the spiritual essence of Saarinen’s Nordic Arts-and-Crafts aesthetic through a combination of strong but simple massing, substantial but never ostentatious materials, subdued colors, contrasting textures, handwrought details, and an overall sense of self-contained dignity. Indeed, they surpass Saarinen by imbuing a workaday athletics building with a mysterious aura akin to that attained by his greatest fellow Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto, peerless humanist of the Modern Movement. The ceiling over the Cranbrook swimming pool is painted midnight blue and features two retractable ovoid skylights that open to the sky, evoking the “clearing in a forest” motif found time and again in Aalto’s interiors.

Another of Williams and Tsien’s outstanding efforts offers an unfortunate demonstration of the vulnerability that even high-style architecture is subject to in an age of cultural gigantism. Their American Folk Art Museum of 1997–2001 was erected on two narrow adjacent townhouse plots on Manhattan’s West 53rd Street, just west of the Museum of Modern Art. That property once belonged to the longtime MoMA benefactor Blanchette Rockefeller, who gave the land to the folk art museum much to the later chagrin of the Modern when MoMA embarked on Yoshio Taniguchi’s massive aggrandizement of 1997–2003.

The American Folk Art Museum opened in the economically shaky aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks and it financial footing was further undermined by the Great Recession later in the decade. By 2011 its trustees felt compelled to sell the Williams and Tsien building to MoMA, which has not said whether it will retain the structure or demolish it to make way for projected additions. Sadly, Williams and Tsien’s brilliant maximizing of an absurdly constrained midblock site—which they overcame with illusionistic sleights of hand much like those John Soane used to turn his London house-museum of 1808–1824 into a marvel of soaring top-lit spaces—never won an enthusiastic public beyond design professionals.

By ingeniously engineering a veritable exoskeleton of concrete, Williams freed almost the entire volume of the building envelope from the interior steel supports of conventional high-rise construction. All the same, a good deal of the space he gained had to be devoted to vertical circulation—stairways and elevators—and the museum’s display areas tended to feel hemmed in at best and mere afterthoughts at worst. Still, architectural aficionados marveled at the ingenuity and care Williams and Tsien invested in this difficult task.

Along with the Barnes, their most recently completed project is the Reva and David Logan Center for Creative and Performing Arts of 2007–2012 at the University of Chicago, which will be formally inaugurated this fall. Situated at the southwest corner of the Midway campus, Logan Center was envisioned not only to consolidate related activities—music, theater, film, dance, studio art, and art history—that had been scattered throughout the sprawling institution, but also to act as a gateway between the school and the South Side community, whose residents (well over 90 percent of whom are black) have long felt alienated from a university they view as elitist and indifferent to them. The striking 170-foot-high tower that makes Logan visible from afar—a syncopated high-rise pylon that subliminally channels the Art Deco flair of Chicago’s 1933 Century of Progress exposition—signifies the welcome being offered there to neighborhood performing arts groups.

The $114 million Logan Center cost about 20 percent less than the Barnes but at 184,000 square feet is twice as large. The rich materials of the Barnes are contrasted here with far more modest components—brick instead of stone, steel instead of bronze, tile instead of mosaic, linoleum instead of parquet flooring, industrial felt wallcoverings instead of custom silk weavings. Yet the architects’ commitment to quality and attention to detail is identical in both schemes, as is the complex organizational planning that fits a bewildering array of functional requirements—at Logan, rehearsal rooms, recital halls ranging from black-box experimental spaces to a full-dress auditorium, screening room, classrooms, offices, and common areas—into a coherent and thoroughly satisfying whole.

The Barnes, however, will be very hard for its architects to surpass. It must now be included among the tiny handful of intimately scaled museums in which great art and equally great architecture and landscape design coalesce into that rare experience wherein these complementary mediums enhance the best qualities of one another to maximum benefit. Such institutions include, for example, Jørgen Bo and Vilhelm Wohlert’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art of 1958–1966 outside Copenhagen, Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum of 1966–1972 in Fort Worth, and Renzo Piano’s Nasher Sculpture Center of 1999–2003 in Dallas. The incorrigibly contentious and gleefully litigious Albert Barnes would probably have railed against the ultimate disposition of his life’s work. Yet what cannot be disputed is that with the final withering of his posthumous grip, a generous vision of art’s life- enhancing potential has at long last come into full focus.