1.

Above all, we should celebrate. The Supreme Court, by a 5–4 vote, has left President Obama’s Affordable Care Act almost entirely intact. So the United States has finally satisfied a fundamental requirement of political decency that every other mature democracy has met long ago, and that a string of Democratic presidents, from FDR to Bill Clinton, tried and failed to secure for us. We finally have a scheme of national health care provision designed to protect every citizen who wants to be protected.

The Affordable Care Act does not change America’s tradition of using private health insurance as the basic vehicle for financing medical care. The scheme it creates is less efficient and rational than a single-payer system like Great Britain’s in which the national government employs doctors and hospitals and makes them available to everyone. But a single-payer scheme is politically impossible now, and the act erases the major injustices that disgraced American medicine in the past. Private insurers are now regulated so that, for example, they cannot deny insurance or charge higher premiums for people already sick. The act subsidizes private insurance for those too poor to afford it, and extends the national Medicaid program that has provided care for some of the very poor to cover all of them.

But it is nevertheless depressing that the Court’s decision to uphold the act was actually a great surprise. Just before the decision was announced, the betting public believed, by more than three to one, that the Court would declare the act unconstitutional.1 They could not have formed that expectation by reflecting on constitutional law; almost all academic constitutional lawyers were agreed that the act is plainly constitutional. The public was expecting the act’s defeat largely because it had grown used to the five conservative justices ignoring argument and overruling precedent to remake the Constitution to fit their far-right template.

The surprise lay not just in the fact that one of the conservatives voted for the legally correct result, but which of them did that. Everyone assumed that if, unexpectedly, the Court sustained the act it would be because Justice Anthony Kennedy, the least doctrinaire of the conservative justices, had decided to vote with the four more liberal justices, Justices Ruth Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. After all, since 2005, Kennedy had joined the liberals in twenty-five cases to create 5–4 decisions they favored, rather than joining his fellow conservatives to provide five votes for their side. Two of the other conservative justices—Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas—had done that only twice, and the two others—Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito—had never done so. So most commentators thought, from the moment the Court agreed to rule on the act, that the decision would turn, one way or the other, on Kennedy’s vote, and a great many of the hundreds of briefs submitted on both sides offered arguments designed mainly to appeal to him.2

But Kennedy voted with the conservatives this time. Moreover, he signed a joint dissent, along with Scalia, Thomas, and Alito, that was, even by the usual standards of those latter three justices, intemperate and in parts outrageous. In the oral argument of the case, last March, Kennedy had suggested that he thought the question of the mandate’s constitutionality a close one. There is no hint of that caution in the belligerent joint dissent.

It was Chief Justice Roberts—who, as I said, had never voted with the liberals in a 5–4 decision before—who provided the decisive vote for upholding the act. There is persuasive internal evidence in the various opinions, and particularly in the joint dissent, that he intended to vote with the other conservatives to strike the act down and changed his mind only at the very last minute.3 Commentators on all sides have speculated furiously about why he did so. A popular opinion among conservative talk-show hosts suggests that Roberts has been a closet liberal all along; another that he has suffered a mental decline.

Almost no one seems willing to accept Roberts’s own explanation: he said, in his opinion, that unelected judges should be extremely reluctant to overrule an elected legislature’s decision. His own judicial history thoroughly contradicts that explanation. In case after case he has voted, over the dissenting votes of the liberal justices, to overrule state or congressional legislation, as well as past settled Supreme Court precedents, in each case to reach a result the right wing in American politics favored. His vote in the regrettable 2010 Citizens United case overruled a variety of statutes to declare that corporations have the free-speech rights of people, and therefore have the right to buy unlimited television time to defeat legislators who do not behave as they wish.

Advertisement

The conservative majority’s opinion in that case insisted that such corporate expenditures would not create even the appearance of corruption. This year the state of Montana pleaded with the Court to rethink that judgment: the state said that the amount and evident political impact of corporate electioneering in the last two years had conclusively demonstrated a risk of corruption. Roberts and the other conservatives did not bother even to explain why they would not listen to evidence for that claim; they just declared, in an unsigned opinion, over the protests of the liberal justices, that they would not.

It is therefore hard to credit that, in so short a time after that contemptuous refusal, Roberts had been converted to a policy of extreme judicial modesty. Most commentators seem to have settled on a different explanation. Recent polls have shown that the American public has become increasingly convinced, by the drum roll of 5–4 decisions mainly reflecting a consistent ideological split, that the Supreme Court is not really a court of law but just another political institution to be accorded no more respect than other such institutions. Roberts, as chief justice, must feel threatened by this phenomenon; the chief justice is meant to be a judicial statesman as well as a judge, and it is part of his responsibility to protect the public’s respect for the Court as above politics. Perhaps he thought it wise, all things considered, to take the occasion of an extraordinarily publicized case to strike a posture of judicial reticence by deciding contrary to his own evident political convictions.

He might have thought this particularly wise in view of the large number of politically charged cases scheduled for hearing in the Court’s next term, beginning in October, a month before the presidential election. The Court will have the opportunity to overrule its 2003 decision allowing state universities to take an admission candidate’s race into account, as one factor among others, in seeking a diverse student body. The conservative justices might wish to abolish affirmative action altogether, or to impose more stringent restrictions on it. They will also have the opportunity to reverse lower courts by upholding the Defense of Marriage Act, which forbids federal agencies to treat gay marriages as real, for example by allowing a gay couple to file a joint income tax return.

The same justices will also be asked to strike down an important part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which requires states with particularly bad voting rights records to seek federal permission for new changes in their election laws. No doubt, moreover, they will soon find a chance further to constrict or even to abolish abortion rights. Roberts may want to blunt the anticipated accusations of political partisanship that any right-wing decisions in these cases will likely attract by supporting Obama’s health care program now. If so, he will have been immeasurably helped by his new enemies in the right-wing media who are painting him as a secret liberal, or as a turncoat villain with a deteriorating mind.

2.

Our eighteenth-century constitution gives Congress only a limited number of legislative powers set out in an enumerated list; no congressional statute is valid unless it can be defended as the exercise of one of those listed powers. Fortunately the framers drafted their list of powers in expansive language that made congressional power sensitive to changing economic and other circumstances. Otherwise the United States could not have developed into a great nation but would have remained an impotent federation of weak and vulnerable states. Throughout our history, however, the most conservative “states rights” justices have tried to interpret these powers narrowly, to give less power to the national government and hence more to the states. On the whole they have failed: as the need for strong national legislation became more and more evident and urgent, more generous interpretations prevailed.

The Affordable Care Act requires everyone, with very limited exceptions, to purchase private health insurance or, if they do not, to pay what it calls a “penalty” levied as part of their income tax. The Obama administration defended that “mandate” by pointing to two clauses in the Constitution’s list: Congress is given the power both to regulate “interstate commerce” and to “lay and collect taxes.” It relied most heavily, in its briefs and in oral argument, on the first of these powers. It argued what seems obvious: that financing health care is a national problem that cannot sensibly be managed in different ways state by state. Few experts challenged that assumption or the further assumption that no national legislation that relied on private insurance could succeed unless everyone, including those least likely to need medical care soon, contributed to the insurance pool. As a backstop, the administration said that if this argument failed, the mandate could be construed as a tax and therefore authorized by the power-to-tax clause.

Advertisement

Roberts rejected the administration’s first claim. He said that the commerce clause does not permit Congress to require people to buy commercial insurance. But he accepted the administration’s second, backstop, claim and so held the act constitutional. That combination of rulings is surprising. By long tradition, as Ginsburg pointed out in her separate opinion, a Supreme Court justice should not offer to decide constitutional issues that it is unnecessary for him to decide. Since Roberts declared the act valid because it is a tax, he had no reason gratuitously to declare that it was not a valid exercise of the commerce power. He should have explained that though the issue of the commerce clause had dominated the long argument about the act, and was thoroughly discussed in the other justices’ opinions, it was not necessary or proper for him to express an opinion about it. His explanation of why he had to declare an opinion was feeble: he said he would not have construed the act as a tax if he had thought it valid under the commerce power. But how can whether a statute is a valid exercise of one congressional power depend upon whether or not it is a valid exercise of another power? Roberts apparently thinks that the case that the act is a valid tax grows stronger as the argument that it regulates interstate commerce grows weaker. That is alchemy, not jurisprudence.

We might explain away the unnecessary pages of his opinion devoted to interstate commerce as simply the residue of the original opinion he wrote before he decided to change his vote. But law clerks with word-processing programs can make dramatic excisions very quickly, and in any case excision would have been easier than inserting his unconvincing explanation why he had to consider the interstate commerce argument even though it was irrelevant to his argument based on the power to tax. Roberts must have had two incompatible aims. He wanted, perhaps for the public relations reasons I mentioned, to uphold the act. But he also wanted to make plain that five of the nine justices are agreed that Congress does not have power to compel economic activity no matter how essential that activity might be to national prosperity or justice. Liberty, as he might put it, always trumps necessity at the national level.

It is extremely important, however, that he and three of the other conservatives did not adopt the dangerous justification for rejecting the administration’s interstate commerce claim that Thomas presented in a short separate opinion. Thomas wants to repeal eight decades of constitutional law by denying what the other eight justices accept: that Congress has the power to regulate economic activity that takes place within one state but has a substantial impact on the national economy. It would have been a catastrophe had Thomas prevailed: we would have been sent back to the unregulated economy of a pre–New Deal era.

Instead Roberts relied on an intellectually questionable distinction. He said that though Congress can certainly regulate activity in the interstate insurance market—it can fix the premiums private insurers can charge and forbid them from charging higher premiums to those already sick—it cannot regulate inactivity by making people buy insurance. That distinction has no basis either in the Constitution’s text or the Court’s precedents or in political principle. (I explained why in the article cited earlier.) Roberts’s ruling therefore creates a new constraint on the powers of the national government, though it is impossible now to predict how significant that new constraint will turn out to be.

In any event, moreover, the distinction between action and inaction is always suspect, in legal contexts as well as everywhere else, because inaction can always be described, differently, as an action. Is running a stop sign the action of driving through the sign or the inaction of failing to put on the brake? If I choose not to buy commercial health insurance, that is, from one perspective, inaction: there is something I failed to do. But from another perspective it is action: I chose deliberately to run a risk—the risk of falling ill without the benefit of the insurance I could have bought. The distinction between action and inaction depends only on a choice of description; it is frightening to think that a matter of such enormous political consequence—whether Congress can construct a national health care scheme—should be thought to turn on a verbal preference. Roberts seemed aware of the problem: he said that practical men, presumably like himself, have no time for metaphysical niceties. That is a familiar excuse for bad philosophy.

The joint dissent of Kennedy, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito escalates that bad philosophy into self-parody. “If Congress can reach out and command even those furthest removed from an interstate market to participate in the market,” they wrote, “then the Commerce Clause becomes a font of unlimited power, or in [Alexander] Hamilton’s words, ‘the hideous monster whose devouring jaws…spare neither sex nor age, nor high nor low, nor sacred nor profane.’” The lurid vision of snapping jaws assumes that the crucial limit on Congress’s power is the line between forbidding and demanding. Once that line is crossed, it supposes, anything goes.

But the powers of Congress under the interstate commerce clause depend on the substantive question of what laws are needed for effective regulation of transactions with a significant national impact. They do not depend on whether those laws happen to be drafted to require or forbid. If there were a lethal national epidemic, whether Congress had an interstate commerce power to force everyone to be vaccinated would turn on whether a uniform national scheme was imperative. It would not turn on whether the law it passed required vaccination of everyone or forbade anyone not vaccinated to leave his bed.

3.

The states that challenged the act claimed that another of its important provisions, not just the mandate, is unconstitutional. The national Medicaid program now provides medical care for certain categories of the very poor, including children, pregnant women, parents of eligible children, people with disabilities, and elderly patients needing nursing home care. It operates as a mixed federal and state program: the federal government provides the necessary funds but the states actually administer the local programs.

The states’ participation is voluntary: they may refuse the federal funds and forgo any Medicaid funds. But if they do accept, they must meet stipulated federal conditions. Initially, some states refused to join the program, but in the end all fifty states participated in it. That is hardly surprising: refusing to join meant leaving their most vulnerable citizens without aid paid out of national funds, that is, mainly by citizens of other states.

The Affordable Care Act, beginning in 2014, dramatically increases the number of people eligible for Medicaid payments: it provides coverage for everyone who falls below 133 percent of the national poverty line. That extension is essential to meeting the act’s goal of providing medical coverage for all citizens who want it. The act leaves state participation voluntary, but, as passed by Congress, it provided that states that decline the extension of Medicaid lose not only the new federal funds but all the funds they received under their existing Medicaid program. Seven of the nine justices—all but Ginsburg and Sotomayor—thought this last provision too coercive and therefore unconstitutional. State budgets would be devastated if they lost their present Medicaid funding so the threat would force them to accept the extension. The federal government may put conditions on money it offers to states, the seven justices said, but not if these conditions leave the states no real option to decline.

I find Ginsburg’s contrary argument persuasive. She pointed out that Congress could repeal the present program without constitutional objection and then launch a new program with increased eligibility. That would involve no coercive threat at all: states would then be as free to accept or reject the new program as they were before. But that argument failed to convince a majority of the Court.

If the Supreme Court finds part of a statute unconstitutional, as most of the justices found the provision that a state that declined the extension would lose all its Medicaid funding, it must decide whether to strike down the entire statute or simply to excise the offensive clause. It decides by asking, essentially, whether Congress would have passed the statute without that clause. In this case, the question is easy to answer. Congress might reasonably expect that in the end almost no state would refuse the extension if the threat of losing all Medicaid funds were removed. A state that had accepted the original program could not claim that it must reject the extension as a matter of Tea Party principle: the principle remains the same when the numbers increase. And how could a state then explain to the poorest of its voters why it had refused relief for them when that relief is paid for by the federal government? True, the governors of Texas, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina quickly announced that they would not accept the Medicaid extension, and they have since been joined by others. But this may just be politics, and as I said, even though several states balked at the original program, they all finally agreed.

Congress, in passing the Medicaid provisions, would have understood, of course, that there was a possibility that one or two or perhaps more states would decline the extension; but it might reasonably have thought that in that eventuality any damage to its goal could be repaired by further legislation. And it might well have thought that even if that was not possible, most of a loaf was better than none. Roberts therefore sensibly declared that the Medicaid extension remained good law even though the coercive threat of losing all Medicaid funds must be abandoned. States would be free to decline the extension while retaining their present federal funding.

However, the other conservative justices—Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito—rejected Roberts’s argument: they insisted that since the threat of the states losing all Medicaid funds if they didn’t accept the extension had been held unconstitutional, the extension itself must be entirely scrapped. That would have eviscerated the act. It is always dangerous to speculate about the motives of justices. When they offer a competent even though unpersuasive argument for their conclusion, it is wisest simply to assume that they were persuaded by that argument. But the other four conservative justices did not offer a competent argument connecting the invalidity of the threat with the destruction of the entire Medicaid extension. They just declared, on no evidence, that the members of Congress would not have passed the extension if they could not also have imposed the coercive condition.

It is therefore worth notice that Supreme Court justices have a personal stake in cases whose results are likely to affect a presidential election. The Court is now split on ideological grounds: its most important cases are decided by votes of 5–4. As many as three new justices may be appointed in the next presidential term and the character of those new appointees—and therefore of the next president—will determine which of the present justices who remain will have the power to enforce his own agenda or protect his own legacy. In the infamous 2000 case of Bush v. Gore, five conservative justices joined to ensure the election of George W. Bush, offering only arguments so weak that they declared that their decision should not be treated as a precedent in later cases. In Citizens United, five conservatives voted to allow corporations to spend unlimited funds in electioneering, a decision that was expected to, and has now been shown to, favor a Republican presidential candidate.

Here it was widely assumed that President Obama’s reelection chances would be damaged if the Affordable Care Act, often called the most important achievement of his first term, was held unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold it is now expected at least marginally to improve his prospects. That explains why Republicans are so angry and Democrats so pleased at that decision. Could it also explain the venom of the joint dissent?

4.

Roberts, as I said, rejected the administration’s interstate commerce claim but nevertheless upheld the act as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to tax. He pointed out that the only sanction the act provides for those who refuse to buy insurance is a special charge levied against them on their income tax return. He conceded that the congressional authors of the act referred to the charge as a penalty, and that Obama had sometimes called it a penalty as well. But he also noticed that people who cannot afford insurance, and who are therefore excused from the extra tax, are hardly treated as lawbreakers. So the mandate operates as a tax, he said, and is therefore constitutional.

These are excellent verbal arguments. But there are more fundamental and important reasons of principle why the act should be understood as authorized by the taxing power. Roberts made his argument apologetically: he said that it would be more natural to treat the act as an attempt to regulate commerce than as a tax. He construed it as a tax reluctantly, he said, only to save it from being invalid. He has been savaged for that decision: his new right-wing enemies say he has opened the gate to a vast extension of government powers.

Why does it matter, they ask, whether it is unconstitutional for Congress to require people to join and use an exercise club, if Congress can declare a special and minatory tax on all citizens who fail to join and use such a club? Most of those others who applaud Roberts’s decision to save the act seem to agree with his suggestion that it is artificial to treat the act as a tax. They would have preferred him to uphold the act as a regulation of commerce, as Ginsburg, writing a concurring opinion for herself, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, suggested he should have done.

I agree with those four justices that the act can indeed be upheld as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce. Roberts and the other conservative justices who denied that Congress has that power must rely, as I said, on an untenable distinction between activity and inactivity. But I disagree with Roberts’s suggestion that it is in some way misleading or artificial to consider the act’s mandate provision a tax. (He said, “The question is not whether that is the most natural interpretation of the mandate, but only whether it is a ‘fairly possible’ one.”) On the contrary, that description captures the real justification for the mandate in constitutional morality.

For centuries the most powerful and influential argument for social justice has been essentially an insurance-based argument. Justice within a political community requires that the most catastrophic risks of economic and social life be pooled. Everyone should be required to acquit his moral responsibilities to fellow citizens, as well as to guard against his own misfortune, by paying into a fund from which those who are in the end unlucky may draw. This conception of social insurance has been the rationale of the great social democracies of Europe and Canada, and taxation has been the traditional—indeed the only effective—means of pooling those risks. Insurance has been the rationale, in this country, of all our great welfare programs: Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, federal disaster relief, among many others.

The Affordable Care Act, out of assumed political necessity, is different—but only on the surface. It uses private rather than public insurance, and it shuns the label of tax. But it is in essence just another, long-overdue, program of risk-pooling. It is therefore irrelevant that young, healthy people are less likely immediately to need the benefits the program provides. Yes, the act will save many of them from catastrophe later in their lives. But the present justification for asking them to participate is not self-interest but fairness.

It is time that our constitutional courts formally recognize what constitutional interpretation has created over two centuries. Of course constitutional law is limited by the document’s text. But we must interpret the text by finding principles that justify it in political morality, and we must test statutes against the text not by abstract semantics but by asking whether the statutes respect those principles. The Chief Justice’s reasoning contains an unwitting insight. The national power to tax is not just a mechanism for financing armies and courts. It is an indispensible means of creating one nation, indivisible, with fairness for all.

The Affordable Care Act’s mandate is not just another example of economic regulation of an interstate industry like cars or steel. It does not impose a tax in the ordinary political meaning. No one thought when the act was passed that Obama had broken his promise not to raise middle-class taxes: that claim is a sudden invention of opportunistic Republicans first denied and then embraced by Mitt Romney. But the act is nevertheless best understood as in the long tradition of mandatory insurance for the sake of justice.

—July 13, 2012

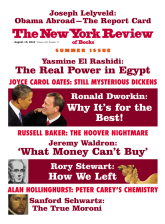

This Issue

August 16, 2012

Egypt: The Hidden Truth

Obama Abroad: The Report Card

-

1

See Brett LoGiurato, “The Odds Overwhelmingly Say That Obamacare Is Finished,” BusinessInsider.com, June 27, 2012. ↩

-

2

So did my own argument in these pages, which quoted extensively from Kennedy’s past opinions to show that he was intellectually committed to upholding the mandate. See “Why the Mandate Is Constitutional,” The New York Review, May 10, 2012. ↩

-

3

See Paul Campos, “Did John Roberts Switch his Vote?,” Salon, June 28, 2012. ↩