Muhammad Mossadegh, the Iranian prime minister overthrown by US and British agents in 1953, was a man who declined a salary, returned gifts, and collected tax arrears from his beloved mother. Frugality was allied to punctiliousness in this droopy-nosed aristocrat who enraged the West by insisting that Iran, not Britain, should own, sell, and profit from Iranian oil. A member of the princely Qajar family, he retained a noblesse-oblige gentility even as he became the symbol of postwar Iranian assertiveness. He fainted, he swooned—and was often pajama-clad. When he saw a hole, he had an irrepressible inclination to dig deeper. High principle trumped judicious compromise too often for Mossadegh to be a successful politician.

Yet even his wavering US-backed nemesis, Muhammad Reza Shah, called him “our Demosthenes.” An ascetic with an extravagant sense of mission, a lawyerly man who lived by Voltaire’s “I may disagree with what you say, but I would defend to the death your right to say it,” Mossadegh was, as Christopher de Bellaigue puts it in Patriot of Persia, “a cussed contrarian.” Just what he amounted to in his brilliant prickliness, and how his quixotic defiance mirrored the Iranian psyche, remain important questions six decades after the United States ousted this European-educated constitutionalist and declared its preference for Middle Eastern strongmen. Mossadeghism failed. Iran never found a stable reconciliation of patriotism, democracy, and faith. Its persecution complex, fostered by British contempt and cemented by an Anglo-American coup in 1953, endured. Just as ownership of oil once was the vehicle of Iranian nationalist ambition, so the vexed nuclear program is today under the mullahs who exploited the blowback from 1953.

Such persistent failure and confrontation raise a question: Could it have been otherwise with Iran? An elegiac tone runs through de Bellaigue’s rich portrait of Mossadegh. He quotes the ousted prime minister, after the coup, saying, “If I am murdered, it will be more useful for the country and the people than if I stay alive”—and notes that even Mossadegh’s “thoughts of death were quintessentially Persian.” Martyrdom is a persistent theme in a Shia nation that teems for a month every year with flagellants mourning the Imam Hussein, the Prophet’s grandson, slaughtered by the caliph in 680 but recalled with all the ardor of a recent passion. In fact Mossadegh survived for fourteen years in the Shah’s nascent police state, first as a nonperson in prison and then confined to his country estate at Ahmadabad. He died at eighty-four, long after the many contemporaries who had fretted over his frailty.

De Bellaigue allows himself to speculate on what might have been:

Mossadegh’s Iran would have tilted to the West in foreign affairs, bound by oil to the free world and by wary friendship to the US, but remaining polite to the big neighbor to the north. In home affairs, it would have been democratic to a degree unthinkable in any Middle Eastern country of the time except Israel—a constitutional monarchy in a world of dictatorships, dependencies and uniformed neo-democracies.

As for social affairs, “secularism and personal liberty would have been the lodestones, and the hejab and alcohol a matter for personal conscience.”

This tantalizing scenario seems a faithful reflection of the man; but of course we will never know. Two years after Mossadegh’s nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) in 1951, the CIA unloosed Kermit Roosevelt and his fellow American agents on Tehran to oust him. The operation, code-named TPAJAX, carried forward to a bloody denouement what Britain’s MI6 had first plotted. The objectives of a rising America and a declining Britain diverged; they overlapped just sufficiently for both to do their worst. Mossadegh, even if he had been spared such execrable meddling, may not have been able to control the swirling currents of communism, Islamism, monarchism, and militarist despotism that the CIA fanned. Iran was fragile, and Mossadegh’s constitutionalism was a nuanced idea in an environment where bazaar toughs with nicknames like Brainless Shaban whipped up crowds.

Still, what we do know is enough to lament the path not taken and to label Operation Ajax a singular disaster. It reinstated the feckless Shah, who had complained to Loy Henderson, the American ambassador, “What can I do? I am helpless.” It turned him into the despot of the Peacock Throne, propped up by the US-trained SAVAK secret police. It quashed Iran’s strong democratic stirrings. It embedded a fathomless Iranian suspicion that would find expression in the seizure of US diplomats after the 1979 revolution. It did nothing to halt British decline, as was evident three years later at Suez. It thrust the United States into the unhappy business of support for Middle Eastern tyrants able, they claimed, to deliver oil and stability—a strategic position at odds with American values that spurred Islamist hostility and was also one of the targets of the hypocrisy-exposing Arab Spring. It set Iran on a self-defeating zigzag between embrace of the West (the Shah) and embrace of the Prophet (the postrevolutionary theocracy), a path that has led to isolation and the alienation of most Iranians from their repressive polity. As de Bellaigue writes, “Few foreign interventions in the Middle East have been as ignoble as the coup of 1953, and few Middle Eastern leaders have less deserved our hostility than Muhammed Mossadegh.”

Advertisement

Mossadegh al-Saltaneh was born in 1882 into a branch of the Qajar aristocracy that controlled the country’s revenue administration, an office he would later describe as synonymous with “thief.” His mother was a cousin of the Qajar Shah, his father a former finance minister forty years her senior. Marriage, as de Bellaigue notes with typical economy, was a way of “allying families, producing heirs and pleasing God”—precepts followed by Mossadegh himself when he wed the daughter of a senior cleric, a union that would last sixty-four years.

The Persia of his youth languished under rulers given to taking the waters at Baden-Baden. But the nation’s indolent patience had limits. Rising prices stirred a rebellion in 1905. The first parliament, or majlis, a concession wrested from the Qajars, opened its doors in October 1906. The quest for some form of representative government in Iran is more than a century old; to imagine it will ever abate is folly.

A constitutionalist already convinced of the need to constrain the monarch through laws, Mossadegh was elected to the majlis, only to be barred on grounds of youth. When the monarch—a “perverted, cowardly, and vice-sodden monster,” in the words of his American financial adviser—bombarded parliament in 1908, Mossadegh set out to join the defense but his courage failed him. Although he could not abide the despot, he was at the same time, as de Bellaigue notes, “tied by his mother to the ruling house and shared the traditional Persian fear of chaos.” From an early age this subtle man with an abhorrence of violence defied facile categorization.

A European interlude followed, first on his own in Paris (de Bellaigue suggests he had a brief liaison there), then with his young family in the Swiss town of Neuchâtel, where he completed a doctorate in law. Mossadegh’s thesis sided with clerical modernizers, arguing that Islamic laws were historical phenomena that might be adapted as society changed. But he came out against imposing European institutions and laws on Iran because “the direct result of imitating Europe will be the spoliation of a country like Iran, for everything should be in proportion with the need.”

On his return, serving as deputy finance minister, he objected to Iran conceding legal jurisdiction over Christian residents to separate Christian authorities. “In order for a country to be independent,” he wrote, “it is necessary that it have jurisdiction over all its residents.” He was so zealous in pursuing a top ministry official for corruption that one observer suggested Mossadegh would “raze Caesarea for the sake of a handkerchief.”

Enduring characteristics of Mossadeghism were coming into focus: a fierce probity and “pebbly pride”; sharp rejection of the quasi-colonial Western domination articulated by George Nathaniel Curzon, a former viceroy of India, who said of Persians, “These people have got to be taught at whatever cost to them that they cannot get on without us”; a constitutionalism that defended the monarchy (as a bulwark against godlessness and communism) but held that kings should reign rather than rule.

As for religion, Mossadegh knew the central place of Islam in Persian identity. He was not especially religious himself. He inquired of his devout wife “what it is that you want from this God of yours, that you should disturb him night and day.” Yet he was drawn to the spirit of selfless sacrifice that he viewed as a high expression of Shiism. “Every Muslim,” he said, “should defend his country, and if he wins he will have endowed the country and the religion with a new spirit.” When, in 1925, a former Cossack calling himself Reza Pahlavi “crushed the shell of Qajar power” and embarked on a fast-forward secular modernization redolent of Atatürk, Mossadegh was appalled by what he saw as gratuitous insults to Islam like the outlawing of the chador in 1936.

Much else troubled him. Reza bulldozed houses to make Tehran look more Western, prompting Mossadegh to the acid observation that destruction of private property was illegal in the West. He admired some reforms—they included the abolition of titles (henceforth he was Muhammad Mossadegh)—but could not rid himself of the impression of “a grubby dictator got up in royal plumage.” At the very outset of Pahlavi rule, Mossadegh rose in the majlis to oppose the resolution abolishing the Qajars. Although “utterly disappointed” with the corrupt dynasty, he scorned its successor: “So, the prime minister becomes sultan,” he commented. “Is there such a thing as a constitutional country where the king also runs the nation’s affairs?” Why, he asked, “did you needlessly shed the blood of the martyrs on the road to freedom?”

Advertisement

Good questions: Iran has taken many false roads to a long-sought liberty since 1905. Ayatollah Khomeini, of course, promised freedom in 1979 when Reza’s son was ousted and he founded an Islamic republic. The promise came to naught. It is now clear that Mossadegh was the last Iranian leader to unite strands of religious and secular nationalism, faith and democracy, and so offer some chance of a reconciliation of the two. But Britain and then the United States were too blinded by his effrontery and too dismissive of the very notion of Iranian national ambition (although Washington demonstrated some understanding) to see more than a nuisance—Newsweek’s “Fainting Fanatic”—in Mossadegh. De Bellaigue writes, “Infusing British policy, the stink in the corner of the room, was a profound contempt for Persia and its people.” The United States, to its cost, would be infected by it.

Oil exploration began in earnest in Iran in 1901 with the award of a concession to a British entrepreneur, William Knox D’Arcy. Here was the seed of what would become the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, then the AIOC, and ultimately the behemoth called BP. Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, oversaw the deal in 1914 that gave Britain control of Iranian oil and ensured the Royal Navy a dependable supply on terms that left Tehran with only small revenues. Reza Shah renegotiated slightly better terms in 1933 but did little to alter Iran’s status as oil lackey of the Empire. Mossadegh was incensed. Iranian oil helped drive the Allied victory in World War II just as it had fueled the British warships in World War I. By 1950 Anglo-Iranian’s profit stood at £86 million. In the same year, Abadan, the Iranian town at the heart of the oil industry, “had only enough electricity to supply a single London street.” When it came to oil, “no one asked the Persians what they thought.” The paternalistic reasoning of the AIOC went something like this: give a little and the damn natives will want everything.

Such dismissiveness toward Iran was the leitmotif of Mossadegh’s life: the Anglo-Persian Agreement of 1919 that turned his country into little more than a protectorate; the humiliating oil deals; the summary Allied occupation of 1941 that led the Shah to abdicate in favor of his young son Mohammed Reza; the contempt after 1945 for an Iran seen as a hapless cold-war pawn. Mossadegh, who kept a small ivory of Gandhi in his room at Ahmadabad (the man in pajamas contemplating the man of the loincloth), was, as de Bellaigue notes, part of a generation of Western-educated Asians who returned home “to sell freedom to their compatriots.”

The British responded with disquisitions on the Oriental mind. In Iran they did not get it. As George McGhee, a US diplomat who negotiated with Mossadegh, remarked, nationalist movements in Iran and Egypt were “examples of a much wider movement in men’s minds.” He urged on the British Foreign Office a change in postwar Middle Eastern strategic policy. The aim: to ensure “that it is recognised by these countries that they are being treated as equals and partners.” His appeal fell on deaf ears—in London and, after November 1952, in the Eisenhower White House.

Mossadegh had emerged from the war as the preeminent advocate of Iranian patriotic and democratic ideals. By now in his sixties, he had endured imprisonment by Reza in 1940—Mossadegh’s violent arrest sent his daughter, Khadijeh, into a depressive spiral from which she never recovered—and knew well the “yawning sense of inadequacy” of Reza’s son, a ruler less than half his age. This young Pahlavi, looking abroad for support, was scarcely the man to confront what the majlis now called the “usurping” AIOC. The oil company’s predations were a growing target of the clergy led by the rabble-rousing Ayatollah Abolqassem Kashani (exiled by the Shah in 1949 only to return eighteen months later) and the well-organized Communists of the Tudeh (“the Masses”) party.

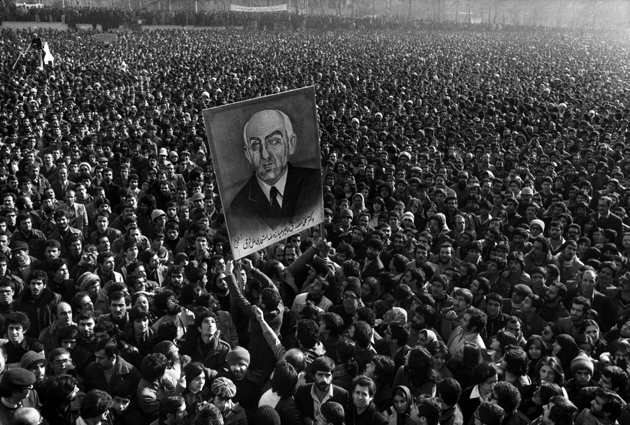

National fury rose over British rejection of a proposed 50–50 profit-sharing agreement; Mossadegh spent much of 1950 meeting with elected deputies at the majlis. On November 25, 1950, members of the parliamentary oil commission called for nationalization. The Shah’s prime minister retorted that this was impossible. Kashani’s Warriors of Islam responded by killing him. On March 14, 1951, nationalization was voted into law. A little over a month later Mossadegh was thrust by the majlis into the role of prime minister. One reporter described “the most extraordinary scenes of pride.” Another wrote: “Long live the memory of those glorious days.”

The days proved numbered. De Bellaigue, fluent in Farsi, draws on previously unused Iranian sources to bring Mossadegh to vivid life. As the plotting of the coup gathers pace, he also demonstrates a deft hand in describing broad political trends and the personal foibles of the main protagonists. British authorities rebuffed the author’s efforts to gain access to MI6 records of the coup—deemed too sensitive sixty-nine years after the event. But the CIA has been forthcoming and the broad lines are clear. Secretary of State Dean Acheson, in a remarkable cable quoted by de Bellaigue, got it right. Postwar Britain, he noted, “stands on the verge of bankruptcy.” He continued: “Therefore, in my judgment, the cardinal purpose of British policy is not to prevent Iran from going Commie; the cardinal point is to preserve what they believe to be the last remaining bulwark of British solvency.”

Britain loathed Mossadegh because it wanted its Iranian oil money back. The United States was focused on a distinct issue, communism. North Korea crossed the 38th parallel in June 1950. Truman declared: “If we just stand by, they’ll move into Iran and they’ll take over the whole Middle East.”

Mossadegh, drawn to America even as he despised Britain, believed this divergence in goals afforded a chance to drive a wedge between the allies. With greater focus, he might have done so. But it seems he never made up his own mind about what might be an acceptable deal. As financial pressure grew from what amounted to a British-orchestrated boycott of Iranian oil, the prime minister busied himself, in the Persian phrase for doomed missions, “riding Satan’s donkey.” De Bellaigue writes, “He was unable to strike that balance, between interests and ideals, of which a true politician is made.”

There were opportunities. On a remarkable forty-nine-day trip to the United States in the second half of 1951, Mossadegh came close to winning over America. Time magazine named him Man of the Year. Moving between the United Nations and Washington, the prime minister stressed the common ground between Iran’s struggle and that of the colonists of 1776: his nation, too, wanted free from “the chains of British imperialism.” Iran, he noted, “has stationed no gunboats in the Thames.” Some, like McGhee, were sympathetic. Truman and Acheson also saw the perils of British gunboat diplomacy.

Indeed, without the rightward lurches in British and US politics of 1952, which brought Churchill and Eisenhower to power, the coup plot might never have coalesced. Churchill blamed his predecessor, Clement Attlee, for the biggest fall in British stature “since the loss of the American colonies nearly 200 years ago.” Eisenhower declared that, to defeat communism, “longstanding American concepts of fair play must be reconsidered.” The Dulles brothers took over at the CIA and the State Department: neither needed “much persuasion that Mossadegh was a dangerous madman tipping his country into the abyss.” Britain had passed the mantle to America: its post-imperial grievances met the new superpower’s fears. It was easy enough for Britain to talk up the Communist threat—never really persuasive in God-fearing Iran. The Eisenhower administration heard what it wanted to hear.

If Mossadegh had seen in time that the price of American friendship and aid was some fig leaf for the AIOC, he might have contrived some workable political space in 1951. As it was, the Anglo-American plot to oust him gathered pace.

There is a troubling mystery with de Bellaigue’s book. Its subtitle in Britain is “Muhammad Mossadegh and a Very British Coup.” In the United States it is “Muhammad Mossadegh and a Tragic Anglo-American Coup.” This looks like an unfortunate marketing ploy. The US subtitle is right. Britain laid the groundwork; America delivered overthrow. De Bellaigue’s description of the initial plotting of Nancy Lambton, an “austere bluestocking,” and Robin Zaehner, a British agent “with a taste for gin, opium and the homoerotic verses of Rimbaud,” is brilliant. Iranian newspapers were bought, tribal divisions probed. Zaehner, asked by a visiting correspondent to Tehran in 1952 what he should read, suggested Alice Through the Looking Glass. The West’s nuclear negotiators can take comfort: they are not the first to be enmeshed in Iran’s political labyrinth.

Mossadegh, at its tangled center, was increasingly alone. He fell out with Ayatollah Kashani, who felt ill-used after supporting nationalization and backing the prime minister when the Shah tried to oust him in July 1952. He had no truck with the Communists of the Tudeh party. His contempt for the Shah was evident, his control of the military partial at best. As on the international stage, he would not pick allies at home. Only the people remained. Mossadegh felt a mystical bond; in large measure it was reciprocated. A messianic streak stirred in the septuagenarian. De Bellaigue writes that Mossadegh “was not a dictator in the sense of a tyrant lusting after power, but he shared the dictator’s sense of his own indispensability.” He was prepared to dissolve the majlis—and did so in a last-ditch attempt to hang on—but not curtail press freedom or authorize violence. Part visionary and part fusspot, writes de Bellaigue: that seems about right.

The plotters had these advantages: the prime minister’s eroded political base, his dithering, and his delusions. They went to work. British diplomats had been expelled from Iran and the embassy closed on October 17, 1952; the leading role passed to Americans. Chief among them was Kermit Roosevelt, “an Ivy Leaguer of private means urging cloak-and-dagger operations.” The favorite tune of the CIA officers in Tehran was “Luck Be a Lady Tonight”: they rode their luck. Roosevelt cozied up to the Shah and got him to fire Mossadegh; he identified a senior general named Fazlullah Zahedi as the man to replace him; deployed agents provocateurs to stir up the Communist threat; dispersed money to the mullahs and the army and newspaper editors. To all of which the prime minister responded by insisting that in a “constitutional country there is no law that is higher than the will of the people.”

That popular support might still have saved him. The coup of August 15, 1953, was a disaster. The Shah fled to Rome in so much haste he forgot to put on his socks. Then Mossadegh dithered. Holed up in his house at 109 Palace Street, he talked on and on about the law. He refused to execute the coup plotters. The Shah was contemplating a new life in the United States, Iran was a republic in all but name—and Mossadegh was nowhere to be seen.

Loy Henderson, the American ambassador, met with him on August 18. He said the United States regarded the Shah as head of state and Zahedi as lawful prime minister. Mossadegh vowed to fight on. In reality he dozed. Roosevelt, scenting victory in defeat, goaded the crowds, got his thugs to smash the windows of mosques, and worked on the monarchist loyalties of the police and army. It must be said that if the coup was an Anglo-American plot, it also involved very Persian self-sacrifice and chaos. Ultimately, writes de Bellaigue, Mossadegh “tied himself up with his own principles. Then he lay down to die.” His description of the denouement at 109 Palace Street and Mossadegh’s unlikely escape is particularly strong.

Mossadegh survived for another fourteen years but his ideals collapsed immediately. Henderson urged the restored Shah to pursue an “undemocratic” Iran. Mohammed Reza was more than happy to oblige for the next twenty-six years.

Hope always seems to beckon in Iran only to be dashed. In 1979 Ayatollah Khomeini co-opted the constitutionalist successors of Mossadegh—like Mehdi Bazargan, the first postrevolutionary prime minister—but then crushed their liberal aspirations and insisted on God’s authority to rule. The mullahs ended up trashing Mossadegh, whom they had briefly honored, as the Shah had before them.

In 2009, as Iranians rose to protest a stolen election, the opposition leader, Mir Hussein Moussavi, with two million people in the streets behind him, hesitated rather as Mossadegh dithered in 1953. Instead of moving forward, Iran circles about: a CIA agent seized in Tehran in 1979 observed that he and other hostages were “surrogates for the CIA of 1953,” and in 2012 Iran’s stop-and-go nuclear program smacks of an attempt to assert Iran’s stature after past humiliations. As James Buchan has observed, “lachrymose intransigence” is the Islamic Republic’s favored mode. It does not get Iran very far.

The United States and the West bear significant responsibility for all those lost Middle Eastern decades since 1953. “Everything should be in proportion with the need,” Mossadegh wrote in his doctoral thesis. The coup was disproportionate. It was reckless and damaging, “that which should not have happened,” in the words of one observer. De Bellaigue’s powerful portrait is also a timely reminder that further Western recklessness toward Iran, at a time of a further “movement in men’s minds” across the Middle East, would only pile tragedy upon tragedy and again put off the day when Iranians’ quest for constitutional liberty can be realized.