Peter Carey is an astonishing capturer of likenesses—not only in the sense of the portrait (the “good likeness”), but of the teeming similitudes with which a sharp eye and a rich memory discern and describe the world. Simile and metaphor, which are at the heart of poetry, are a less certain presence in prose fiction, in some novelists barely deployed at all, but in Dickens, for instance (with whom Carey is repeatedly compared), they are vital and unresting elements of the novelist’s vision.

In Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda (1988), a tiny detail may speak for much: “Mr. Tomasetti had passion, but it was of a different type. It was as cold as a windowpane in a warm room. It was this she trusted.” In a phrase Carey makes an unforgettable observation, encapsulates Mr. Tomasetti, says something too of Mrs. Burrows, the Sydney widow who “liked a little distance” in her men, and adds as it were a further facet to the mysterious thematics of his novel, in which the properties and manufacture of glass are a major preoccupation. As always when Carey is at his best (and that novel remains one of his most thrilling achievements), the reader has the elated sensation of figurative language working so closely with observation that the whole book is revealed as a marvelously live and organic unity.

Oscar and Lucinda takes place in the mid-nineteenth century, Dickens’s time, and a period to which Carey has returned in several novels, including his new one, The Chemistry of Tears. He has always been at ease in that era, and has written about it in many different aspects, with none of the research-heavy self-consciousness of too many historical novels. “The past is not dead, it is not even past” is the epigram from Faulkner at the front of True History of the Kelly Gang (2000), Carey’s invented first-person narrative of the Australian outlaw-hero. He finds a voice for his long-dead narrators that deftly frees them from the constraints and hazards of pastiche.

In the case of Ned Kelly there is one remarkable piece of source material, the “Jerilderie Letter,” a document of over seven thousand words dictated by Kelly to his fellow outlaw Joe Byrne in 1879, a year or so before his death at the age of twenty-five or twenty-six. To read it and then read Carey’s novel is to see an extraordinary act of homage, assimilation, and expansion, Kelly’s pungent and unpunctuated narrative voice inhabited and subtly expanded, with no sense of strain, as the voice of what is both a gripping adventure and a somberly hypnotic prose-poem. Carey, the poet of likenesses, finds on occasion a fellow poet in a man who has lived by his wits in the wild, seeing a kind of meager magnificence in the world and his struggles with it:

When he finally locked the door on me I were very hurt but still able to climb up on the crib and here there were sufficient light to see the yellow bruises surface slowly on my sallow Irish skin. I watched them like clouds changing in the spring sky thinking of my father and what horrors he endured in silence.

It is not merely the lift of language, but the indescribable sensation that all the properties of Kelly’s world, the mountains, trees, shacks, horses, family, women, police, all prosaically themselves, are also elements in something visionary, caught in transition between historic fact and national myth.

In his new novel there is much play on questions of likeness. In the story’s present day (2010), Catherine Gehrig, a horologist at the fictional Swinburne Museum in London, learns that Matthew, the married fellow curator who is her secret lover, has died, very young, of a heart attack. Her sympathetic superior, Eric Croft, arranges for her to work, as a kind of therapeutic exercise and also to get her out of the museum, on the restoration of a mid-nineteenth-century German automaton, a highly elaborate swan that when fixed will appear to swim and preen its feathers and swallow fish. In the packing cases containing this disassembled marvel (oddly its intervening history is not investigated) are notebooks containing the journal written by Henry Brandling, the English gentleman who in 1854 had gone to the Black Forest to find someone capable of making him a mechanical duck, fallen in with a domineering genius called Sumper, and returned home with a good deal more than he’d bargained for.

His purpose in having a duck made was to revive his tubercular son Percy by means of the healthful “magnetic agitation” of interest and pleasure he would take in the automaton. His text is a “day journal” kept supposedly as raw material for letters to his beloved Percy, but in fact a record of his extreme anxiety and bewilderment. As Matthew is buried, so the journal is exhumed, and through the rest of the novel Catherine will have to face, with varying emotions of horror, resentment, and fascination, the repairing of a fiendishly clever simulacrum of life, an “undead thing,” “so dead and not dead it would give a man goose-bumps.”

Advertisement

So two stories, a century and a half apart, are set to alternate and resonate. Carey has used paired narrators to great effect before. In Theft (2006), a very enjoyable art-forgery romp is really of secondary interest to the contrasting self-portraits of the two brothers, Michael and Hugh Boone, who take turns telling the story. Michael is a once-acclaimed artist fallen on hard personal and professional times, and perhaps an easier voice to capture, but it is characteristically in the self-portrait of the physically huge and mentally “subnormal” Hugh that the book is at its most original and involving. Much about Hugh is unexplained: his life, with all its perils, is as it is, and his presence as a constant and familiar worry in Michael’s life is an inescapable given. Hugh puts words and phrases into capitals, with the unnerving ironic purpose of the mad; and there are certain connexions with the idiom of Ned Kelly in the running-on unpunctuated clauses, as there are in the unforced lift into transcendent apprehension of the mundane. If his brother is the artist, he is the poet. “The old ute had no air-conditioning just a DUCT opened by a foot-long lever which caused the release of long-trapped dust. Lord what perfumes—honey and gum blossoms and rubber hoses.”

In his most recent novel, Parrot and Olivier in America (2010), Carey also split the narration between the aristocratic Frenchman Olivier de Garmont and his English servant Jack Larrit, known as Parrot, each creating his own larger memoir and self-portrait while providing sharp ironic comment on the other. Olivier is on the way to being a celebrated writer, but again it is the disadvantaged Parrot who is the artist (he has trained as an engraver) and, in his own narration, a sometimes rapturous lyrical poet, especially of his Dartmoor childhood:

I had been no closer to the sea than a beach or two where my da and I had gone fossicking for useful storm wrack although we never found any more than a dented christening cup and oaken kindling sanded to velvet by the fury of the sea.

The novel is set variously in England, Australia, postrevolutionary France, and 1830s America. Neither strand of it has any ambition to be period pastiche, and we enjoy Parrot and Olivier as complex speaking characters rather than as feats of historical ventriloquism. Carey is not one of those storytellers who on entering a room feels an anxious need to describe everything in it and how and where it was made, so that a novel seems to have mated with an encyclopedia.

Sometimes, indeed, an anachronism punches a small hole in the period fabric. “I’ll break your frigging arm,” says a character a good century before the OED’s first instance of “frigging” as an expletive by John Dos Passos in 1930, while later on Olivier bizarrely tries out the 1940s phrase “shoot the breeze.” But the reader hardly thinks of either strand of the novel as being “written” by its narrator (even if Parrot speaks finally of handing his text to a compositor), and the book’s nature as a kind of historical fantasia frees it from the ties of strict documentary accuracy; the italics suggest Carey knows he’s chancing it.

In the new novel, both narrators are constrained by circumstances from such freewheeling fun. Both of course are unbalanced by powerful emotion, Catherine “high on grief and rage,” “off her face with rage and cognac,” abruptly confronting a life without a future, Henry consumed with anxiety about his ill son, whose future he hopes almost desperately to prolong. Henry Brandling is a man of limited self-awareness, out of his element—“a rather dull chap really,” he describes himself, and Catherine thinks at first he is “thick as a brick,” though in time she becomes “deeply invested” in him. Much of his journal is given up to his fractious relations with the automaton-maker Sumper, the appearances of the faintly uncanny long-fingered child Carl who works for him and may be a genius (may indeed turn out to be the engineer Karl Benz), and the record of Sumper’s abstruse rants, lectures, and tall tales, some of these about yet another genius, Sir Albert Cruickshank, with whom Sumper worked in London on a vast prototype computer (and who may well be a version of Charles Babbage).

There is much that is curious in this material, and the spooky Black Forest setting brings pleasing echoes of the Brothers Grimm, or “Brothers Cruel, as my mater called them.” The beak of the swan will be made by a silversmith called Arnaud who is himself a gatherer of fairy tales, a “collector of ancient cruelties.” The German landscape is rich in enigma and menace, heightened by Henry’s—and thus our—only vague understanding of what is being said and done around him. His narrative has the repetitive bafflement of an anxiety dream.

Advertisement

It’s reassuring that Catherine herself can find it exasperating: “One was often confused or frustrated by what had been omitted. The account was filled with violent and disconcerting ‘jump cuts’”; “you soon learned that what was initially confusing would never be clarified no matter how you stared and swore at it.” But here and there throughout are memorable evocations of the kind that Carey normally lavishes on every paragraph—the “mousey skittering” of a piece of paper pushed under a door, or the German valley, “the azure sky, the dry goat paths like chalk lines through the landscape, the bluish granite which contained the stream, the harvesters still swinging sweetly on their scythes as if it required no effort in the world.”

Another pleasure is the sensation of being played with by Carey, as he leads us through terrain between fact and fiction. Though his Ned Kelly was of course a real person, with an established history, Carey has generally preferred to investigate history through fictional characters modeled more or less closely on actual figures, but under other names, and untrammeled by the needs of biographical accuracy. So Oscar Hopkins in Oscar and Lucinda, and his naturalist Plymouth Brethren father, were evidently based on the young Edmund Gosse and his father Philip, vividly described in the former’s great autobiography Father and Son; but Oscar’s fate, as a self-destructive gambler and disgraced clergyman in New South Wales, is that of someone quite different. (We know from the first page that Oscar, like Ned Kelly, will die at the age of twenty-five.) The aristocratic Olivier, in Parrot and Olivier in America, was evidently based in some significant respects on Alexis de Tocqueville. Here we have a version of Babbage, as well as a version of the eerily extant (though in fact much older) mechanical swan that can be seen at the Bowes Museum in County Durham (and in numerous YouTube clips). And here, as in Parrot and Olivier, various period images and documents are reproduced in facsimile, to tease us with the historicity of the fiction.

There are anomalies, even so. In Henry Brandling’s narrative, unlike Olivier’s, Carey is claiming to present a historical document, a journal quite specifically written in 1854; here again a number of anachronisms may be mere fictional license, or reasonable guesses that for instance “potty” (meaning a bit mad) might have been idiomatic some time before its first recorded usage in 1920. But still, “you scared the pants off Hartmann,” an idiom first recorded in 1925, “ashtray” (1887), “guff” (US, 1888), “bumph” (1889, and then only as bumf, for bum-fodder), “programmer” and “programme” as a verb (1948 and 1945), are all more or less jarring. When Brandling uses terms like “celluloid” (a plastic invented in 1870) and “snookered” (when the game of snooker wasn’t named till 1889), you start to feel that Carey, a supreme virtuoso of language, who besides can look these things up as easily as I can, must be aiming at some deliberate alienation effect. To what end, though, it is rather hard to say.

These are tiny pedantic points, no doubt, but they contribute to the oddly unhistoric feel of Brandling’s narrative, which it is hard to believe in as a mid-nineteenth-century journal (it is closer perhaps to the hyperactively exclamatory dramatic monologues of Robert Browning, in which it’s equally easy for the reader to be unsure what exactly is being talked about). Catherine’s chapters have a different status—it’s not clear we’re meant to think of her writing them at all, and they exist in the customary space of much first-person narrative, somewhere between journal and inner monologue.

Still, it’s disconcerting when on the first page a simile is botched. Catherine is told of the death of her lover by a wailing woman with a mouth “folded like an ugly sock”; even allowing for the transferred epithet (it is the effect, not the sock itself, that is ugly), this doesn’t quite come off—it seems an ugly impatient shot at a figure. Three pages later, Catherine too is crying, and “now I was the one whose mouth became a sock puppet”—suddenly we see a Kermit-like gape, and the image has come into focus. This is a risky strategy, to convey the deranging effect of emotion through the narrator’s loss of verbal exactness.

Other similes are too vague, too purely subjective to work: “he covered my hand with his own—it was large and dry and warm like something you would hatch eggs in”—what? a nest? (but then it would be the wrong way up); some sort of mechanical incubator? The image doesn’t bear much scrutiny. (Compare the surprising but beautiful simile for the glass factory in Oscar and Lucinda: “Where outside it had been untidy and damp, inside it was very neat and pleasantly dry, like the palm of a pastrycook’s hand,” where the unmentioned flour of the pastrycook matches the unmentioned sawdust and ashes of the glassworks in a friendly association of different trades.) Likewise, Carey would scarcely before have allowed a character to write that something was “the tip of the iceberg”—throughout his work he has seemed effortlessly to avoid this sort of cliché.

Both narrations show to a newly exacerbated degree a tendency in Carey to compacted and elliptical storytelling. In Parrot and Olivier, it could sometimes be hard to get one’s bearings, so great was the bustle of activity and the vigorous certainty about unexplained matters shown by the two narrators. Establishing shots were rare. The whole novel was conducted at a tremendous, vivid, and largely enjoyable rush, in which nonetheless certain other kinds of enjoyment, of stillness, inwardness, the less highly colored and less audible textures of life, were rarely glimpsed. The tempo was that of headlong picaresque.

In The Chemistry of Tears it is as if Carey’s impatient energy has accelerated further. Both Catherine’s and Henry’s stories are wildly subjective and elliptical, written generally in very short ejaculatory paragraphs, often of just a few words. This relentlessly staccato manner is a plausible way to convey disturbed mental states, heightened emotions of fear, anger, panic, grief, as well as the dislocations of drink, and the local effects it produces are often brilliantly vivid, even if a story told this way can leave the reader breathless and emotionally unengaged. (It’s an inevitable consequence of this technique that the normal Dickensian warmth of Carey’s characterization is pinched and warped by the narrower preoccupations of Catherine and Henry.)

In his last two books Carey has seemed more interested in process than occasion, in the rapid, barely graspable, subjective flux of life. There is a lot of activity, but there are almost no scenes—if by scene one means a sustained piece of action over several pages that advances and illuminates the narrative; and so the few that there are register strongly: for instance, an unexpected visit to Catherine’s flat by Matthew’s two sons, who wish to give her the Suffolk cottage where much of her affair with their father was conducted, and who bring with them such haunting reminders of the dead man (“his father’s hair, exactly, the big nose, the full-lipped humorous mouth”), as well as being so savorously their youthful selves, smoking, drinking, “musty and unwashed.” For a while the complex human drama emerges movingly from the jumble of Catherine’s solipsistic monologue.

Against this impression of characters and incidents glimpsed by flashes of lightning, certain thematic ideas are pressed pretty heavily. The mechanical nature of the doomed human body, and the human desire to create further mechanisms with untold potential for destruction, are constantly insisted on. Henry’s wife is “driven by a hot engine,” Catherine reflects that “we were intricate chemical machines,” she herself becomes “a whirring, mad machine,” the dead Matthew becomes “a factory, producing methane,” the tear glands are “intensely complicated factories,” Carl is producing an “engine” and himself becomes “the engine of the workshop,” the museum where Catherine works is a “great mechanical beast,” London itself a “suicidal engine.” Henry, recording Sumper’s claims about “the Engine” of Cruickshank, says of himself, “I was Percy’s engine.”

When Catherine’s assistant in restoring Sumper’s engine, Amanda Snyde, becomes hysterically obsessed with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010, obsessively watching videos of it on her computer, it is the internal combustion engine that takes the ultimate blame. Cruickshank, too, we discover, was motivated by loss, that of his wife and three children in a shipwreck caused by faulty sea charts. From the “grieving cavern of his mind,” he sought to produce mechanically perfect charts, “WITHOUT HUMAN INTERFERENCE” (the hectoring capitals here are Henry’s way of marking Sumper’s emphasis as he tells the story): Henry records of him that “the Engine and the Madness were the same.” Our efforts to invent, to improve and delight ourselves, march inexorably with our will to self-destruction: of some such thesis the distracted characters of the novel seem a little too obviously to be the exponents.

Against this again, and the source of many brief lyrical passages where Catherine recalls her earlier happiness, is the insistence that knowledge of our mechanical natures need never diminish “our sense of wonder, our reverence for Vermeer and for Monet, our floating bodies in the salty water, our evanescent joy before the dying of the light.” Crying itself is eloquent of the unfathomable interactions of our physical and emotional beings. As it happens, Carey has written about the chemistry of tears before. In a scene in Oscar and Lucinda, the two main characters are both crying but for different reasons. “Both lots of tears were salt, I am sure, and were probably within the normal range of salinity, i.e., between one per cent and two per cent salt, but this is merely to show you the limits of chemistry”—Lucinda’s tears being produced by anger and confusion, Oscar’s by unexpected “joy, wonder, humility and love.” Chemistry tells us only so much.

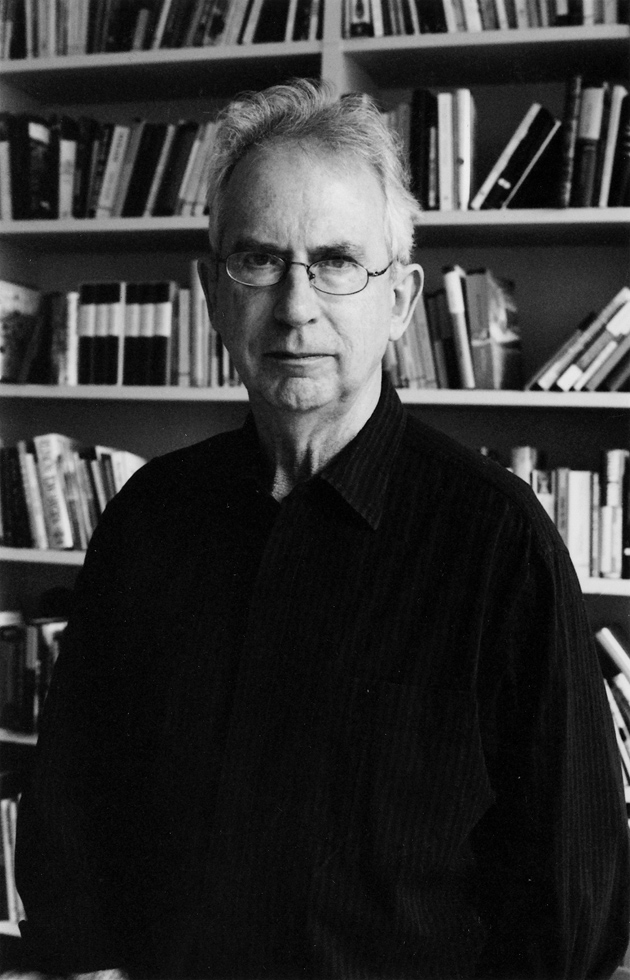

In the final chapter of the new novel, Eric Croft tells Catherine that “tears produced by emotions are chemically different from those we need for lubrication,” her tears of grieving recollection containing “a hormone involved in the feeling of sexual gratification, another hormone that reduced stress; and finally a very powerful natural painkiller.” Here chemistry seems to tell us rather more, to be a kind of diagnostic aid. If we are animals driven by our hormones, it is to them too that we owe the highest flights of happiness and creativity, and some relief from our inner pain.