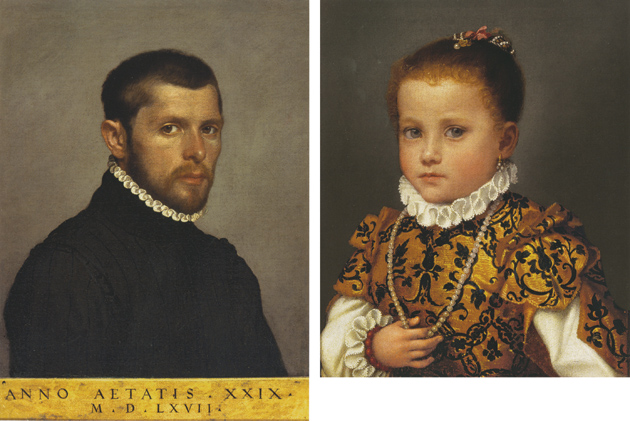

The catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition “Bellini, Titian, and Lotto: North Italian Paintings from the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo” has on its cover, amusingly, a work by Giovanni Battista Moroni. Perhaps the designer of the appealingly small-sized catalog chose the Moroni, a 1567 portrait of a young man with a background of a neutral color, because, more than other pictures in the show, it provided a good space to set forth the lengthy title. But the cover could be saying, editorially, that while Bellini, Titian, and Lotto are the presumed attractions, it is Moroni’s image of a tense young man, with closely cropped hair and beard, that genuinely grips our attention.

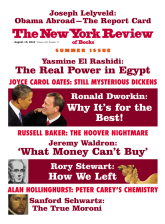

This, anyway, is what happens at the exhibition, a presentation of a dozen or so fairly small-size paintings from one of Italy’s premier museums. Covering works made in Venice and elsewhere in northern Italy between roughly 1450 and 1570, the show gives us the opportunity of seeing choice and unusual pictures by Giovanni Bellini and Titian, probably the most acclaimed figures of the Renaissance in Venice, and by some of their lesser-known contemporaries. But it is Moroni’s portrait of the intent young man, and the artist’s hardly less phenomenal portrait of a little girl—paintings that, in their emotional directness, seem as if they could have been done the other day—that make the show momentous. Once they are encountered, all the other pictures somehow go on hold.

Viewers with even a working familiarity with the history of Western art can be forgiven for drawing a blank with the name Moroni. A native of the region around Bergamo, in the foothills of the Italian Alps—a region that was then a part of the Venetian Republic—he was active in the middle years of the 1500s, and died, probably in his fifties, in 1578. He made religious pictures, usually for the local valley churches, but he specialized in portraits. He did so to a degree that was unusual, and earned him Bernard Berenson’s sneering 1907 remark (and the quotation most associated with the artist) that he was “the only mere portrait painter that Italy has ever produced.” Berenson went on witheringly, and his verdict was burnished by a later eminent art historian, John Pope-Hennessy, who, in a 1966 book on Renaissance portraiture, noted that while Moroni’s realistic pictures give an unsurpassed sense of the sitter’s appearance, this immediacy comes at “the expense of shallowness.”

It makes perfect sense, and it attests to the artist’s power, that connoisseurs such as Berenson and Pope-Hennessy seemed almost affronted by Moroni, because his portraits have a bluntness that has few precedents in Italian painting. Moroni is an artist most of us discover by chance, though his status as a little-known master is slowly changing. He received his first show in 1978, four hundred years after his death, at London’s National Gallery, which has a number of his works in its collection. The Accademia Carrara followed with his first Italian retrospective the next year, and in 2000 the Kimbell Art Museum, in Fort Worth, gave him his one American exhibition, a small show accompanied by a catalog that provides perhaps the fullest and best account of the artist in English.

Moroni’s work became clearer to New York audiences when, in 2004, the Met presented “Painters of Reality: The Legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy.” This was a complex, illuminating, and far from crowd-endearing exhibition. It was heroic of the Met to delve into a subject—realism and naturalism in northern Italian art between the late 1400s and the middle of the eighteenth century—that was replete with so many unfamiliar artists, many of whom seemed embraceable only by specialists. It was not always clear, moreover, what the connection to realism was for the exhibition’s many portraitists, painters of religious scenes, explorers of the new genre of still life, and artists of peasant and rural life. Art in Lombardy in those centuries, it turns out, mirrored, uneasily, allegiances both to a northern European exactitude about the appearance of people and of the natural world and to perhaps more purely Italian affinities with expressive gestures.

Among the few painters to make immediately distinct impressions were Moroni and the slightly younger Sofonisba Anguissola, who was represented by riveting paintings and drawings of herself and of her family members. The artists, who were certainly aware of one another (she was from Cremona), were like two sides of the same coin. They both looked penetratingly at their subjects, but where Sofonisba’s people are summed up by the way their faces crinkle as they smile, or gleam with contentment, or cry, Moroni makes the emotions of his subjects enigmatically hard to decipher.

Advertisement

His sitters generally look straight out at us, and they do so in a way that suggests that they have complex inner lives. It is not a note found in the portraits of, say, Holbein (who was a generation older than Moroni), perhaps because Holbein, with his incisive delineation of every aspect of a face, seemingly catches a particular moment in the sitter’s life, while Moroni is after something broader. This depth is felt in his people regardless of their age or sex. Portrait of a Little Girl of the Redetti Family (circa 1570), in the Met’s show, presents someone who might be four, and, meeting her composed, clear-eyed person, it is hard to turn away from her. The other Moroni here, Portrait of a Twenty-nine-year-old Man, from a few years earlier, is an even more substantial work, if only because the sitter has such a forceful physical presence, and the composition itself, where many earth and flesh tones, and black, are set off by little zones of stone gray and white, is stunningly assured.

From the sumptuous or elegantly subdued clothes of his sitters, and from what is known about them (some remain unidentified), we can tell that Moroni’s subjects were scholars, diplomats, in the military, or merely prosperous. But like our perhaps wary—or possibly reproachful, or merely watchful—twenty-nine-year-old, they can’t be called characters. They never seem sunk in their thoughts, or distant, and while a few are on the verge of smiling, we never think that we look at someone who is inherently genial, say, or superior, or vain. In this they resemble our sense of Moroni himself. He was “renowned throughout North Italy,” Andrea Bayer writes in the catalog of the current show; but about what he was like as a person—he might, or might not, have been married and the father of two boys—few hard details have turned up.

The painter’s best-known work, Portrait of a Man, which is in London’s National Gallery and is informally known as The Tailor—it shows someone with shears in his hand and a bolt of cloth before him—stands out in part because it is the rare Moroni where the sitter is actually doing something. (It doesn’t hurt that the man is good-looking, and the way he leans over a little, and turns to face us, gives the portrait a kind of inner spring.) But this London picture, which has the generally bare appearance of many Moronis—he doesn’t, like Holbein, make something luxuriant out of the space surrounding his sitter—conveys little about what it was like to be a tailor at the time. It presents if anything the idea of being a tailor (or of being a cloth merchant), and Michael Levey, in his 1987 The National Gallery Collection, astutely saw that the sitter, with his appraising look, might as well be taking “the spectator’s measure.” This is Moroni’s tone in his portraits in general: his people scrutinize us.

What also feels fresh and modern—and capable of making earlier commentators believe there was something obdurate or lacking in Moroni—is the unusually straightforward, almost anonymous, nature of his realism. Just as his subject seems to be consciousness itself—or people in states of sheer mental readiness, uncolored by one definite thought—so his formal approach appears to be untouched by any personal inflections or mannerisms. He didn’t make eyes or noses or the length of a sitter’s face in an identifiable “Moroni style,” but, rather, delineated forms in a way that is close to some normative idea of representation that we carry in our heads.

And while he didn’t paint thickly, it looks as though he did. Especially with his male faces, which can be fairly ruddy (and make one want to call him an Alpine rather than an Italian artist), he gives paint a sculptural, malleable presence. His most inventive works, which are images where a donor prays before the holy family, may have evolved from this feeling for skin. No other artist seems to have handled the theme the way Moroni did. In the traditional manner, donors exist in the same world as the Virgin or saints. Moroni, though, shows his donor as essentially a contemporary person—we can tell by his clothes and realistically weathered face—while the holy figures are painted in a pat and bloodless way. The resulting pictures (there is an example in Washington’s National Gallery), where one painting style is laid flat on another, could be called collages.

Made during the heyday of the Counter-Reformation, when the Catholic Church was attempting to revive its hold on a restive laity, the pictures may have been meant to show how personal and intense religious devotion could be. To our eyes, however, the works are quietly revolutionary. Making us uncertain whether the donor is having a vision, or is merely standing before a painting, they show religious experience as almost by definition ambiguous.

Advertisement

Moroni’s seemingly meaty paint surfaces jump out in the current show in part for the simple reason that the other pictures are fifty or many more years earlier in date. The figures and settings in these paintings by Lotto, Giovanni Bellini, and such little-known artists as Bergognone and Andrea Previtali are set in a more delicate, and ornamental, Renaissance world. With the exception of a mythological picture by Titian, where the brushwork is meant to be felt, paint itself is not very tangible in these works. The images seem to exist beneath the surfaces of the pictures, and to be determined by the drawing—by the outlines of forms.

The Accademia Carrara has lent these paintings because it is currently closed for renovation. The Bergamo museum, which dates to the late eighteenth century, has been built on the holdings of a string of knowledgeable collectors; and the works chosen for this show bear out this history in being understatedly superlative. The Bellini, for instance, a close-up of Christ, the Virgin, and Saint John after the Crucifixion, is marked by the startling purity of John’s tear-stricken grief. With his fist resting with an odd prominence on Christ’s shoulder, he is literally and poetically taking over the picture.

The Bergognone, of 1490, entitled Saint Ambrose and Emperor Theodosius I—it shows a meeting of the two fourth-century figures in an urban setting—implies by its title an esoteric subject. In purely visual terms, though, it is a completely accessible, and jewellike and funny, scene of two power brokers and their respective followers running into each other. The imploring hands of the saint and the I-don’t-have-time-for-this gesture of the emperor describe their positions completely. The various henchmen do their best to listen in, and because of the appearance of the clothes of the many little people walking in the street in the background, this part of the picture looks as if it were occurring in 1910 or so.

Titian’s Orpheus and Eurydice, to take one more work, is hardly a major painting; but the charmingly specific depiction of the Underworld as a fiery factory, and the hilly setting—with Orpheus and Eurydice flitting across it like ballet dancers—draw us in. Done around 1510, when the artist was in his early twenties, it gives a foretaste of the dancelike aspects of his crisply painted mythological scenes, and it foretells the flickering appearance of the works of his old age. Titian’s is one of the grandest names in the history of art, yet for some of us (or at least for me) his pictures can produce less a sense of excitement than a measured admiration. For viewers who feel this way, Orpheus and Eurydice is a gift: it makes you want to see, at the very least, where he went next.

The Moroni portraits on view, which weren’t in the Kimbell exhibition or “Painters of Reality,” have an awakening force as well, though of a more profound order. Moroni, it should be said, wasn’t an artist with anything like Titian’s ambition. Spending all of his life in either Bergamo or the nearby and much smaller Albino, his hometown—it is uncertain whether he ever got to Venice—he was in some ways a provincial; and apart from his donor pictures, he didn’t transform his approach much over the years (an approach that, at moments, could wind up with dour-spirited likenesses). It might be added that when he made full-length portraits Moroni was like painters of every rank and era in having trouble animating the lower half of the works. Standing before the bewitching little girl in the present show, however, or before the young man, who beautifully evades our desire to define his thoughts, any caveats about the artist fall away.

A painter whose portraits have a bluntness with few precedents in Italian painting