A white friend told me recently that he heard someone complain that he’d voted for the black guy last time around, did he have to do it again—as if Obama’s election had been a noble experiment we weren’t ready for. Only the big boys can deal with the global economy, so hand the keypad to the White House back to its rightful class of occupants, those big boys who helped to make the mess in the first place. President Obama got little credit from Wall Street for bailing out the financial system. Imagine the criticism had he not or had he tried to institute even more reform at that moment. It was an early display of his administration’s hope to lead by consensus.

Obama’s hold on the middle ground frustrates old liberals and engaged youth. But it remains one of his great assets that the Republicans can’t shove or provoke him from the middle ground. His entrenchment is perhaps why his opponents cannot make him lose his cool, his own understated black swagger. Think of the fierce need among Republican congressmen to try to insult him as chief executive. More so than his record, the accomplishments of his first term, his cool is his campaign’s best remedy for the negative messages that will get under the floorboards of the nation’s consciousness, placed there by Citizens United, the worst Supreme Court decision since Dred Scott.

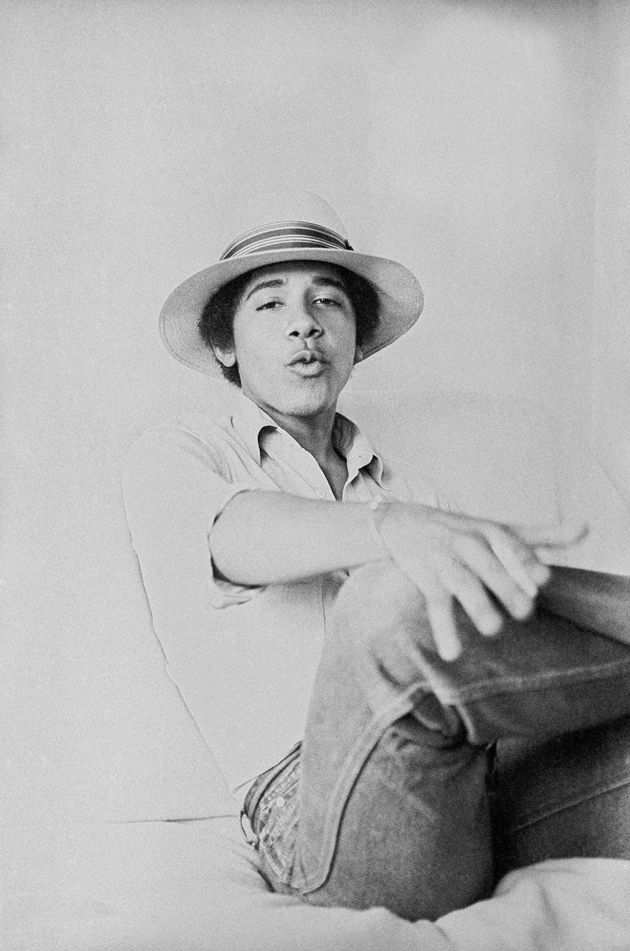

No matter what, the Republicans are promising to bring Obama’s first term to a close with another budget crisis. The first term is becoming the story, the referendum. Meanwhile, Obama’s fight for a second term has had the curious effect of making books about his rise somewhat passé. We are familiar with the exoticism of his story: the absent African father; the young white anthropologist mother in Indonesia; the basketball team in Hawaii. We know about Chicago, the discovery of the black community and the future First Lady. YouTube has him when at Harvard. And then that Speech. Moreover, we know much of this from Obama himself. Dreams from My Father is justly famous.

Yet David Maraniss in his proudly sprawling Barack Obama: The Story presents a biography of the president that he is determined goes deeper than anything else out there. He is clearly pleased to have reached previously untapped sources. Barack Obama: The Story is well over five hundred pages and at its end the future president is just twenty-seven years old, on his way to Harvard Law School. Many share his subject, but Maraniss is the large beast come to the watering hole.

As with men of destiny, Obama’s story begins long before he was born, and so Maraniss opens with the suicide of the president’s maternal great-grandmother in Topeka, Kansas, on Thanksgiving Day, in 1926. Great-grandfather Dunham was a philanderer; his wife took strychnine in despair, providing Maraniss with the first of many extended scenes in which he enlarges upon relevant facts by infusing tangential, atmospheric facts into the telling. “The most recent census noted that the coal furnace needed repair.” The president’s grandfather and his older brother were brought up by their maternal grandparents—“a generational pattern,” one of several such generational patterns that Maraniss believes he has identified in Obama’s story. Moreover, this upbringing was in El Dorado, Kansas, and Maraniss digresses into what Milton, Voltaire, and Edgar Allan Poe have to say about the legend of El Dorado in order to score the irony of a brave town on the dusty Plains named for a city of gold. Maraniss finds little ironies everywhere, like the car crash on Highway 54 outside Eureka at 8:30 pm on November 4, 1935, that killed four friends of Stanley Dunham’s who’d wanted him to come out with them that night. “The genealogy of any family involves countless what-if moments.”

Their great-grandfather told the two Dunham brothers yarns about his time in the Union Army during the Civil War and Maraniss portrays Stanley Dunham as another storyteller, a “dreamer, schemer, and misfit.” It would appear that Maraniss has exposed every lie poor Stanley Dunham ever told in high school. His vagueness of character, his failure to realize a career, had a great deal to do with what the president’s mother and the president himself would look for in their lives, according to Maraniss’s schedule of human causes and effects. Maraniss informs us—because he can—that the summer of 1936 when Dunham graduated from high school was the hottest ever on record in Kansas, and then launches into the formative years of Obama’s maternal grandmother, Madelyn Payne, by then a smart girl hoping for a life beyond the farm.

Advertisement

Maraniss does not forget the history of Kansas as a Free State. El Dorado had been founded by settlers who opposed slavery. Because it will matter, he has researched the racial climate Obama’s grandparents experienced when growing up. Violently segregated Oklahoma was only an hour’s drive away from Madelyn Payne and the Klan had marched in Augusta, Kansas, her hometown, in 1925, but the prevailing sentiment in Kansas was paternalistic, Maraniss concludes. An interviewee back in Augusta remembered for him the town’s two black families when Payne was a teen and that they were real nice. In addition, Payne’s high school history teacher was an Abraham Lincoln buff. “They listened to ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ by Gershwin” as well.

Southeast Kansas was oil and kafir corn (cattle feed) country, boom and bust territory, until rescued by war industries. While Obama’s grandfather was in England and France during World War II in an ordnance supply company, his grandmother, already a mother, was an assembly inspector at Boeing in Wichita. Peace put her out of work and on the road to California, not for the first time, not for the last time, as Stanley Dunham searched for himself and for a living. The president’s mother, Stanley Ann Dunham, named for a Bette Davis character, not her father, was a sensitive girl who by the time she was fourteen had lived in “nine different houses in Kansas, California, Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas again, and finally Washington State. Her parents never owned their own place.” Through connections, her father found yet another new job selling furniture in Hawaii.

Obama’s Luo family originated in northwestern Kenya, but migrated to Kanyadhiang in western Kenya, near Lake Victoria, in the 1820s. Because his family had been in the village only four generations, Obama’s paternal grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama, was sometimes referred to as jadak, meaning foreigner, immigrant, or alien, we’re told. He was a Muslim convert, yet he drank. He could read and write in English and had acted as an interpreter for the British and their African porters, cooks, and laborers during World War I. For a while he had a license to carry a rifle, a rarity for a black man under colonial rule. After a confrontation with a rival chief, he took his radio, bicycle, two of his five wives, and three children off to his ancestral home.

The president’s grandmother, Habiba Akumu Obama, the fourth wife, fled her husband’s violence. “The story line in Kenya had parallels to the one in Kansas: a mother removing herself from the scene, leaving young children behind.” She returned to her own family, while he lived mostly in Nairobi, far from his homestead, working as a supervisor of domestic staff for colonial officials, but in touch with the nascent anticolonialist movement:

What is most striking in retrospect about Hussein Onyango is the way he straddled different worlds, black and white, rudimentary and modern, superstitious and rational. He was Eastern in religion, Western in dress and demeanor, African in political sensibility. Here again was a variation of a characteristic passed down from generation to generation and across the world: an Obama who could operate in distinct cultures but was not wholly absorbed by any. There were times, foreshadowing the circumstances of his American grandson, when he was dismissed by some of his own people for acting white, or not seeming black enough, in his case rejecting too many totems of Luo heritage.

In The Path to Power (1982), the first volume of Robert Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson, LBJ’s father got the arrogant “Bunton strain,” not the softness of his Johnson forbears. Maraniss also works with the silver threads of family temperament. Former neighbors recall the Obama men as arrogant. Maraniss claims to be writing the story of an uncommon family and that President Obama can best be understood not only by how family and environment shaped him, but also by how he reacted to them.

Not many Kenyans attended Anglican mission schools, but Barack Obama Sr. was suspended from high school during the emergency of 1952, because authorities feared that a student protest he headed had links to the Mau Mau insurgency. He worked mostly as a clerk in Nairobi until 1959, when he met an American Christian missionary who was setting up a literacy campaign. Obama eventually worked as her assistant in the program office. The US had become the place to go for the generation of young Kenyans who wanted to help to build the nation after the independence they expected (and that finally came in 1963). In the meantime, Maraniss has given us lots of side trips, into Jackie Robinson’s story, because he was one of the sponsors of an airlift of Kenyan scholarship students to the US, into the missionary’s story, as well as the story of Obama Sr.’s friendship and rivalry with Tom Mboya, a rising star of the independence movement.

Advertisement

Maraniss goes so far as to summarize in detail the article about the University of Hawaii in The Saturday Evening Post that first got Obama Sr. interested in the island. He has even tracked down how much the magazine paid for the piece:

The generational progression of every family is the product of chaos, of countless chance encounters and unlikely occurrences, some more apparent than others. It is easy to see the direct role that Tom Mboya and Betty Mooney played in turning Barack Obama toward higher education and America, but who would expect that a magazine writer from California named Frank J. Taylor, someone Obama never met, would be the one to direct his journey toward a specific location and school?

Here is a biographer with a calm faith in his synoptic method of composition:

My perspective in researching and writing this book, and my broader philosophy, is shaped by a contradiction that I cannot and never intend to resolve. I believe that life is chaotic, a jumble of accidents, ambitions, misconceptions, bold intentions, lazy happenstances, and unintended consequences, yet I also believe that there are connections that illuminate our world, revealing its endless mystery and wonder. I find these connections in story, in history, threading together individual lives as well as disparate societies—and they were everywhere I looked in the story of Barack Obama. In that sense, I reject the idea that every detail in a book must provide a direct and obvious lesson or revelation to be praised or damned. I believe the human condition is more ineffable than that, and it is by following the connections wherever they lead that the story of a life takes shape and meaning.

For all his respect for the part that chaos plays in our lives, Maraniss, the author of several books, is a great believer in synchronicity. In Barack Obama: The Story, he interweaves the American family beginnings with the African family beginnings, then Barack Hussein Obama’s story with that of Stanley Ann Dunham, up to their meeting in 1960. “Here is when, where, and how the two unlikely family stories of this chronicle weave into the same cloth.” The president’s parents were both enrolled in Elementary Russian 101. “There is no record of what attracted them to each other.” Yet he surmises that they’d become lovers within weeks of their having met, because she discovered herself pregnant sometime before Christmas. She was a freshman and didn’t know he was married and had two children in Kenya.

The Luo would say that he was not Kenyan, but all Luo, “despite the fact that Barry Obama’s Luo father was never part of his life. The son would later write that he was separated from his father when he was two, but that is received myth, not the truth. For these Obamas—Ann, Barack, and Barry—the Hawaiian word for family, ohana, did not apply.” The divorce was made final in 1964.

Stanley Ann Dunham’s story is moving, how she went back to school and struggled as a single mother, then met her second husband, Lolo Soetoro, a geographer from Indonesia. She and her young son moved to Yogyakarta on Java in 1967, at a difficult time in Indonesia, politically. Obama’s sister, Maya, was born in 1970. Though her second marriage also ended in divorce, in Indonesia Ann found the anthropological work that defined her life. Barack Obama Sr.’s alcoholic’s bitter life after he left Harvard without his doctorate in economics is also a tragic story about the tribalism that ruined Kenyan politics after independence, including the assassination of Obama’s fellow Luo, Tom Mboya. But their stories are just part of Maraniss’s long wind-up for the big pitch.

Maraniss’s aim is to become the source, the repository for information about President Obama’s early life that you didn’t know you didn’t want until Maraniss offered it. However, as “Barry” grows up, another aim becomes clearer. This biography mounts a challenge to the veracity of Dreams from My Father, the refined literary memoir that has been waiting for Maraniss down by the kiss-my-black-ass corral.

Occasionally, Maraniss compares the young Obama to the young Bill Clinton, whose biography he has also written. He has evidence of ambition in Clinton’s vow to his mother that he was going to be president someday, and in his thirst for student offices. Robert Caro says he could identify early on LBJ’s hunger for power and follow it throughout his career. But Maraniss can’t find in Obama’s story the scene when he revealed to someone that he possessed a sense of having an extraordinary destiny. He can’t find it, though it is in his hands: Dreams from My Father is that moment. He does see Obama’s memoir, with its admission that he experimented with drugs while in college, as a subtle maneuvering into position for a run for office. However, because Dreams from My Father is the text in his way, so to speak, Maraniss takes it on, attempts to take it down, and in doing so diminishes the importance of the story Obama tells in his book: how he became a black American.

Maraniss’s competition with Dreams from My Father makes him a prisoner of his material, resulting in a sort of biographer’s Stockholm Syndrome about those he has interviewed. Often you get the feeling that because they gave him so much of their time, their trust, and that he bonded with them in some way, he bestows on them the glory of his narrative sun. But these are not insider views of a war cabinet. A young man’s life has made for a long book.

The archive Maraniss is dealing with consists of teachers’ recollections, yearbooks, campus literary magazines, egghead letters to an intellectual girlfriend. The witnesses from Obama’s past are playmates in Indonesia, basketball pals in Hawaii, “Choom Gang” buddies in California. Friends and girlfriends written about in the memoir are composites. Maraniss spent a lot of time with Obama’s Punahou and Occidental gangs, working out who was who. You end up somewhat embarrassed for the former girlfriend of his Columbia days who made her sweet young woman’s diaries available to Maraniss. Relatives, friends, the president himself—Maraniss enlists his cast in his calling out of Dreams from My Father for the discrepancies between the facts and the way Obama tells his story:

As Stanley and Madelyn recounted the north Texas scene to their grandson decades later, or at least as he related their stories in his memoir, there were at least three race-tinged events during their years that stuck in the family lore. The first, according to Stanley, came when he reported for work at Popular Furniture and was told by his coworkers that black and Mexican customers could be accommodated only after normal store hours and had to arrange their own deliveries. The second was when Madelyn, who went to work at a bank in Wichita Falls, was chastised for addressing the black janitor as “Mister.” And the third was when Stanley Ann herself was ridiculed by her classmates and neighbor kids as a “Nigger lover” and “dirty Yankee” for playing innocently with a black girl; Stanley was advised by a parent, “White girls don’t play with coloreds in this town.”

There is no doubt that events of that sort happened in Vernon during that era, though the accuracy of these specific accounts is uncertain.

Maraniss has checked it out and nobody among Madelyn’s friends back in Vernon, Texas, remembered anybody thinking of her as a Yankee and furthermore the captain of the football team at the time was black. Maraniss forgives the grandparents, knowing that they just wanted their mixed-race grandson to know “they were racially sensitive in a racially insensitive culture.” Maraniss goes on to cite a passage in Dreams from My Father in which Obama acknowledges his grandfather’s “penchant for ‘rewriting history to conform with the image he wished for himself.’” Maraniss strongly implies that this tendency is another generational pattern he has uncovered.

Maraniss notes that there is “no documented record” of the love affair between Obama’s parents. “The only other account comes from Ann Dunham herself, recalled decades later but filtered through the writing of her son, who had his own narrative imperatives around which to frame her words.” Or: “Anecdotes that reveal more about him and the way he interpreted family events than about his mother.” And: “Her son seemed to circle around the question in the memoir he wrote decades later, when he related the scene where his mother revealed that her relationship with Lolo had taken a life-changing turn.” It is his mother, after all.

Heretofore undisclosed fact: “Within a month of the day Barry came home from the hospital, he and his mother were long gone from Honolulu, back on the mainland….” End of fact, beginning of speculation: “The question of why they left is what lingers, unresolved.” Evidence of fudge in Dreams from My Father: “In his account, the family breach would not occur until 1963, when his father left the island.” Verdict: “That version of events is inaccurate in two ways.” Proof: “The date: his father was gone from Hawaii by June 1962, less than a year after Barry was born, not in 1963. And the order: it was his mother who left Hawaii first, a year earlier than his father.” Supposition suggested by undisclosed fact: the circumstantial evidence leads back to Obama Sr.’s behavior with women. He was abusive. Maraniss declines to pass sentence on Obama’s mother for the “understandable fudge.” “A mother was talking to her son about a sensitive subject, her relationship with his father around the time he was born, and in doing so she was trying to make the son feel better about the father he never knew.” But Maraniss hasn’t solved a mystery or mediated between characters in his story. The real point is that he has found yet another example of Obama’s memoir not conforming to facts.

For Maraniss, these examples are numerous, like trout in a stocked pond. When Obama relates his mother’s explanation for why their little family broke up, Maraniss must caution: “Shards of truth in all of it, but obscuring a very different reality.” He minds those moments in Dreams from My Father when Obama describes incidents that may have been accurate reflections of his perspective, but nonetheless are about situations and emotions that are beyond the comprehension of someone the age Obama was. “He was an adult when he wrote that, planting thoughts back into the mind of a boy.” Maraniss is sometimes perplexed by the inconsistencies he comes across, but mostly he is full of understanding:

His memory probably tricked him when he tried to re-create the scene decades later. There was no such article in Life; it must have been some other magazine. But that is not the point. The story conveyed what was going on in his mind during those final years in Indonesia, when he became attuned to color in a way he never had before.

The corrections go on: that freak-out with his rich white girlfriend after they saw a black play never happened; the consulting firm where he worked after Columbia was nothing as sleek as he’d said; a black minister in Chicago who had been important to him at one stage was “lost in the novelistic haze of conflated chronology and pseudonyms.” Maraniss’s corrections pursue Obama to Africa, where Obama Sr.’s third wife, also a white American, disputes that her meeting with her late husband’s American son happened the way he said it had in his memoir. Maraniss is particularly alert to where in his memoir Obama shifts emphasis, invents characters, or changes chronology in order to “accentuate his journey toward blackness,” even though he can’t undermine Dreams from My Father or make a case about cynicism in Obama’s discovery of his blackness. “Self-perception is inarguable, one feels what one feels,” he allows.

But if Dreams from My Father is Obama’s declaration of selfhood, it is his self-definition that Maraniss tries to take away from him by recasting him not as self-invented, but as the sum of inherited characteristics and traumatic circumstances:

Leaving and being left were the repeating themes of Barry Obama’s young life. His mother leaving his father. His father leaving the family. Mother and son leaving Honolulu for Seattle. Mother and son leaving Hawaii for Indonesia. Son leaving Indonesia for Hawaii. Son being left with his grandparents in Hawaii. Mother and father rejoining him in Hawaii and leaving him again for Indonesia and Kenya. All in the continuum of the family history. Ruth Armour Dunham leaving life altogether as a young mother. Her boys being left twice in succession, first by her, then by their father. Stan and Madelyn leaving again and again—leaving El Dorado in search of el dorado.…

The adult that Barry Obama became was shaped by this cycle of leaving and being left. It taught him, inevitably, how to adjust to unsettled circumstances, but at the same time it led him on a long search for order and home…. Having a black African father and a white American mother, dealing with people who regarded him as black, or hapa, or Ambonese, or different in one way or another—all the issues of race intensified the outsider aspect of his character. Yet it does not diminish the importance of race to note that the formation of his persona began not with the color of his skin but the circumstances of his family—all of his family, on both sides, not just the absent father, as the title of his memoirs suggests. All of his family, leaving and being left.

Obama does not really emerge in Maraniss’s biography. He remains someone who can only be inferred from the evidence, keeping his reserve, his distance.

Some autobiographies present biographers with the difficulty of their having got there first, forcing them to be reactive. Manning Marable’s exhaustive biography of Malcolm X functions as a concordance to The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Michel Fabre and Hazel Rowley had the humility as Richard Wright’s biographers to recognize that his autobiography, Black Boy, is a great work. It failed to speak to Obama in his youth, though you would expect the urgency of Wright’s prose to have attracted him. But one thing Wright did not have was cool.

Dreams from My Father is intriguing but not mysterious. It is about race and identity on almost every page:

Would this trip to Kenya finally fill that emptiness? The folks back in Chicago thought so. It’ll be just like Roots, Will had said at my going-away party. A pilgrimage, Asante had called it. For them, as for me, Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land, full of ancient traditions and sweeping vistas, noble struggles and talking drums. With the benefit of distance, we engaged Africa in a selective embrace—the same sort of embrace I’d once offered the Old Man. What would happen once I relinquished that distance? It was nice to believe that the truth would somehow set me free. But what if that was wrong? What if the truth only disappointed, and my father’s death meant nothing, and his leaving me behind meant nothing, and the only tie that bound me to him, or to Africa, was a name, a blood type, or white people’s scorn?

I switched off the overhead light and closed my eyes, letting my mind drift back to an African I’d met while traveling through Spain, another man on the run.

As the explainer of himself, Obama is cool in his transparency. Billy Bathgate is his kind of narrator, fluent, graceful, and company Maraniss can’t keep.