1.

When James Holmes, a twenty-four-year-old neuroscience student from the University of Colorado, walked into a midnight premiere of The Dark Knight Rises in late July in Aurora, Colorado, and opened fire, killing twelve and injuring fifty-eight, the national spotlight was, once again, trained on America’s peculiar romance with guns, and gun violence. As after the shootings at Columbine, Virginia Tech, and a Tucson shopping mall, gun control advocates revived their calls to ban guns and gun rights advocates renewed their arguments that if more people carried guns, killers like James Holmes might have been stopped. National politicians, meanwhile, including President Barack Obama and Republican nominee Mitt Romney, expressed sympathy but steered clear of proposing any specific reforms, apparently unwilling to take on the National Rifle Association. When, just a few weeks after the Aurora killings, a white supremacist gunned down six worshipers in a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, the response was virtually identical: plenty of sympathy, but no solutions.

While the Aurora and Oak Creek massacres justifiably sparked the nation’s horror and sympathy, the deeper tragedy is that every single day in this country, more than thirty people are killed by guns. Few of these everyday victims generate national headlines; indeed, gun homicide is so routine that many do not even warrant a local news story. But it is the decidedly nonglamorous, quotidian infliction of death and serious injury by gun owners that deserves our focused and sustained attention. And politicians’ cowardice in the face of the NRA is not the only obstacle to meaningful reform; an even greater hurdle lies in the fact that we seem willing to accept an intolerable situation as long as the victims are, for the most part, young black and Hispanic men.

The United States has had a long romance with firearms. Evidence of the affair can be found as far back as the Constitution, which contains a hotly disputed right to bear arms as the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights, following only the First Amendment’s protections of speech and religion. Our infatuation with guns pervades popular culture, from Gunsmoke and The Rifleman to gangsta rap, Dirty Harry, and Sam Peckinpah’s glorification of self-defense in Straw Dogs. The NRA has over four million members. Americans own 280 million guns, an average of close to one gun per person in the country. Forty-five percent of American households possess a gun.

The United States also has a long history of gun violence. In 2009, there were 11,493 gun homicides in the US.1 In a comprehensive review of the social science literature, the Harvard Injury Control Research Center found solid evidence that the more guns that are available in a jurisdiction, the higher its homicide rate will be. If George Zimmerman had not been permitted to carry a gun, much less “stand his ground,” Trayvon Martin would probably be alive today.

Like so much else in the United States, the costs of our infatuation with guns are not evenly distributed. In 2008 and 2009, gun homicide was the leading cause of death for young black men. They die from gun violence—mainly at the hands of other black males—at a rate eight times that of young white males.2 From 2000 to 2007, the overall national homicide rate remained steady, at about 5.5 per 100,000 persons. But over the same period the homicide rate for black men rose 40 percent for fourteen- to seventeen-year-olds, 18 percent for eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds, and 27 percent for those twenty-five and up. In 1995, the national homicide rate was about 10 per 100,000; the rate for Boston gang members, mainly black and Hispanic, was 1,539 per 100,000. In short, it is not the typical NRA member, but young black and Hispanic men in the inner city, who bear the burden of America’s gun romance.

2.

Is there anything to be done about gun violence in America? One solution would be to ban guns. The United Kingdom does that, and its homicide rate is about one quarter that of the United States. But as Adam Winkler notes in Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America, constitutional, political, and practical obstacles stand in the way of any such solution in the US. The constitutional obstacle, the main concern of Winkler’s engaging and erudite account, has existed only since 2008, when, in District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court struck down a Washington, D.C., gun control law, and for the first time announced that the Constitution’s Second Amendment protects an individual right to bear arms.

Until that time, legal precedent and conventional wisdom held that the Second Amendment protected only a state’s right to maintain a militia, and not an individual’s right to bear arms independent of the state’s need for a militia. (The amendment provides, somewhat awkwardly and ambiguously, that “a well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”) In 1991, former Chief Justice Warren Burger, a conservative Republican, said that the idea that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to bear arms was “one of the greatest pieces of fraud—I repeat the word ‘fraud’—on the American public by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime.” Yet just seventeen years later, in Heller, five justices proclaimed that the Framers had intended to protect an individual right to bear arms.

Advertisement

Ironically, the NRA did everything it could to stop Heller from reaching the Court. Afraid of a negative result, the organization urged that the case not be filed, tried to take it over when it was, and attempted to render it moot through legislation. All its efforts failed. The Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence, the NRA’s most consistent nemesis, was also worried, and tried unsuccessfully to dissuade the District of Columbia from appealing the Heller case to the Supreme Court.

In the end, Winkler suggests, both sides may have won. While the Court’s 5–4 decision was widely seen as a victory for gun rights advocates, Winkler argues that the decision was also something of a compromise. At the same time that the Court, with Justice Antonin Scalia writing, recognized an individual’s right to bear arms, it also emphasized that the right did not preclude the close regulation of gun owners. Heller made clear that the state and federal government can bar felons from possessing guns; prohibit the presence of guns in places such as courthouses or schools; license gun sales; ban dangerous and unusual firearms; and in some instances ban possession of guns in public. Despite his avowed commitment to original intent, Scalia pointed to no historical evidence to support these specific regulations, leading Richard Posner to accuse him of practicing “faux originalism.” Nelson Lund, a conservative Second Amendment scholar, said that Scalia did not use originalism at all, but “a disguised and incomplete form of the [Justice Stephen] Breyer interest-balancing approach that Scalia disdainfully dismissed.”

Few other gun control laws have been invalidated since the Heller decision, except for Chicago’s, which was the second most extreme in the nation. Most courts have upheld most laws against guns, referring to Justice Scalia’s list of permitted regulations. Dennis Henigan, the Brady Center’s legal director, told Winkler that Scalia’s opinion was in the end “a pleasant surprise”; it “encompassed our entire agenda. It basically made it very easy for lower courts without a whole lot of difficulty to find that whatever gun law is at issue in the particular case in front of them…had been blessed” by the Supreme Court.

Winkler makes a convincing case that despite the extremist and partisan divisions over gun rights, this sort of compromise—in which an individual right is recognized but may be subject to substantial regulatory limits—is both practically sound and historically supported. As a pragmatic matter, in a country with 280 million guns, a gun ban, he argues, is simply not feasible. Even if a ban were politically possible, it would fail in practice, much as Prohibition did. Many people would not turn in their guns, and a black market would quickly take hold.

Moreover, as a historical matter, the right to bear arms has long existed at the state level. Forty-three of fifty state constitutions recognize an individual right to bear arms. Federal laws, of course, trump state constitutional limits, but most gun regulation is enacted and enforced at the state level, where it must respect the state’s constitutional limits. So most people in the US had a right to bear arms, based on state constitutions, long before the Supreme Court announced a federal right in Heller.

But Winkler also shows that, notwithstanding the NRA’s zealous opposition to virtually any limits on guns (including to bans on assault weapons and “cop-killer” bullets), regulation has coexisted with the right to bear arms from the beginning. In colonial times, citizens were subject to regular inspection of their weapons at “musters,” and many localities mandated safe storage and barred concealed carrying of guns. The “Wild West,” Winkler writes, was much less wild than it is portrayed, and frontier towns routinely required visitors to turn over their guns to the sheriff upon entering town, resulting in little crime or gun violence. The NRA itself, originally organized to improve marksmanship, supported gun control from the 1920s through the 1960s, until a radical contingent took it over in 1977 and installed as its president Wayne LaPierre, who viewed every effort to regulate guns as a move “to eliminate private gun ownership completely and forever.”

Advertisement

Most gun owners, Winkler writes, are far more reasonable than the NRA, with sizable majorities favoring licensing requirements, background checks, and mandatory gun safety lessons for gun purchasers. But the NRA, backed by gun industry dollars, is thought to be so powerful that even quite limited regulatory proposals are often dead on arrival (including, for example, a bill that would have barred purchase of the “drum magazine” James Holmes used to increase the lethality of his assault weapon). An April 2012 PEW Research Center poll suggests that the NRA is winning on this issue, as 49 percent of respondents favored gun rights while 45 percent favored gun control.

In short, the principal impediment to reasonable gun regulation is not the Second Amendment or the Supreme Court, but the unwillingness of politicians—including both presidential candidates—to take on the NRA. We are left, then, with a country awash in guns, and in laws full of loopholes that make it easy to avoid regulation altogether. For example, federal background checks, which have halted more than a million gun sales to felons and other unauthorized persons since they were put in place in 1994, don’t apply to so-called “private sales”—i.e., sales by unlicensed sellers—at gun shows and elsewhere, which account for 40 percent of gun purchases. In addition, the assault weapons ban was ineffectual as written and has since expired. And as Holmes’s purchases of thousands of rounds of ammunition over the Internet illustrate, Web sales are virtually unregulated, making it easy to amass arsenals well beyond any legitimate need. Reforming such laws might not stop someone like Holmes, who had no prior record and apparently obtained his weapons legally, but they would make access to many of the weapons used in mass atrocities more difficult. On past performance, however, it seems doubtful whether the tragedies in Aurora and Oak Creek will lead to meaningful gun regulation. Pew repeated its poll on guns after Aurora and found respondents’ views basically unchanged.

Gun rights advocates are often concentrated in southern, western, and rural regions, where official law enforcement is less present and individualistic notions of self-defense are common. But as I have noted, the people who pay the most in lives lost for our inability to regulate guns effectively are young black men living in the nation’s poorest urban neighborhoods. The racial divide on this issue rarely enters the debate over gun control, but it ought to. Is it morally acceptable to celebrate and protect a right that leads, predictably and consistently, to dramatically and disproportionately reduced life expectancies for young black men?

3.

If nationwide gun legislation is politically unobtainable, are there local initiatives that might help limit the everyday tragedy of gun violence? Many are now looking to New York City for possible solutions. New York has experienced an unprecedented and hitherto unimaginable decline in crime rates over the last two decades, as Franklin Zimring shows in his provocative and hopeful book, The City That Became Safe. While the average American city saw a 40 percent decline in crime between 1990 and 2000, New York City’s decline has lasted twice as long and has been about twice as large. Rates of homicide, robbery, and burglary dropped more than 80 percent from 1990 to 2009, and automobile theft is down 94 percent.

As Zimring puts it, if accurate, this is “the largest crime drop ever documented [in the US] during periods of social and governmental continuity.” Despite recent reports of pressure within the NYPD to underreport crime in order to achieve such numbers, Zimring concludes, using several independent measures, that the decline is largely real, not manufactured through false reporting.

What’s more, New York achieved these outcomes without significant changes in demographic, economic, or social factors often thought to determine crime rates. Between 1990 and 2005, for example, rates of drug use in New York were constant, but drug- related homicides dropped by 95 percent. New York’s black and Hispanic youth population increased over the period, which many criminologists would predict would lead to increased crime, yet crime fell dramatically. And most significantly, New York City reduced crime while also reducing incarceration rates. Between 1990 and 2008, the nation’s incarceration rate grew by 65 percent, but New York City’s incarceration rate fell by 28 percent. By 2008, there were ten thousand fewer New York City residents in prison than in 1990.

Zimring concludes that New York City’s lesson is one of hope: it establishes the “inessentiality of urban crime”; shows that crime can be reduced dramatically without relying on incarceration; refutes the “superpredator” thesis of John DiIulio and James Q. Wilson that particular social groups inevitably commit crime at high rates; and shows that controlling crime does not require fundamental transformations in the social and economic factors often thought to drive criminal behavior.

The question, of course, is what caused New York City’s success? Zimring concludes, by process of elimination, that policing practices made the difference, or at least, the difference above and beyond the 40 percent decline achieved by the average American city. But many things changed in New York policing between 1990 and the present, and all more or less at the same time.

Was it New York’s increase in the numbers of police, started by Mayor David Dinkins, and supported by President Bill Clinton’s initiative to make federal funds available to put more police on the streets? Was it the introduction of Compstat, an accountability system that allowed much closer tracking of crime, particular offenders, and police performance on a precinct-by-precinct basis? Was it the focused targeting of “hot spots” and drug markets, or the emphasis on enforcing gun laws?

Was it, as the police claim, the city’s aggressive use of “stop-and-frisk” policies, involving hundreds of thousands of searches of young black and Hispanic men? Or was it the “broken windows” policy, in which police broadly enforce minor quality-of-life infractions such as vandalism, public drinking, or prostitution in the hope that by restoring a sense of “order,” more serious crime will also drop?

Zimring finds insufficient evidence to conclude with certainty which of these practices contributed to New York’s success, or by how much. He nonetheless hazards some educated guesses. He finds it most probable that the increased numbers of police, better supervision and accountability of the police, and the police focus on hot spots were the most important contributors, since there is some evidence from elsewhere that these initiatives make a difference.

He rules out the much-vaunted “broken windows” strategy, however, finding evidence that the NYPD did not actually use it. For example, the police never increased arrests for prostitution, a commonly cited quality-of-life crime. He speculates that this is because the New York police were not interested in an across-the-board “broken windows” approach, and instead engaged in targeted arrests on “pretexts,” in which they used minor crimes to go after persons they suspected of more serious crimes, but for which they lacked sufficient evidence. Since most prostitutes are not likely to commit violent crimes, this quality-of-life offense was not a useful pretext, and was ignored.

By contrast, where low-level offenses could be used to arrest people on pretexts, the NYPD enforced the laws against such offenses zealously and selectively. NYPD arrests for misdemeanor possession of marijuana, for example, were relatively steady from 1978 to 1995, fluctuating between about 1,500 to 3,000 a year. Thereafter, however, they skyrocketed. They reached over 50,000 in 2000, and were still over 46,000 in 2009. Marijuana possession, a common crime, is pretty evenly distributed by gender, race, and ethnicity. Studies show that whites use marijuana in slightly higher proportion than their representation in the population, and women and men are roughly equal users. Yet 93 percent of those arrested for using marijuana in New York were men, and 88.7 percent were black or Hispanic.

As Zimring shows in the table reproduced on this page, these arrest rates bear no resemblance to marijuana use rates, but are uncannily consistent with arrest rates for robberies and burglaries. The police appear to be using these drug arrests not to control drugs, but to arrest people who fit their profile of robbers and burglars—a profile that appears to be dominated by race. That the demographics of misdemeanor marijuana arrests track the demographics of robbery and burglary arrests does not mean, of course, that those arrested for marijuana are robbers or burglars—only that they are of the same race or ethnicity. Arrests for marijuana possession have, in short, become a tool for racial profiling, not enforcement of the “broken windows” strategy.

The NYPD’s aggressive stop-and-frisk practices also overwhelmingly target black and Hispanic men, and here the numbers swamp those for marijuana arrests. Between 1990 and 1995, New York police subjected about 40,000 people a year to stops and frisks. In 2011, that number had soared to 685,724.3 Blacks and Hispanics make up 52 percent of the city’s population, but 84 percent of those stopped and frisked. After examining six years of NYPD data and controlling for many nonracial variables, Columbia law professor Jeffrey Fagan found that race predicts stop patterns.

Many of these stops are unconstitutional. The Supreme Court ruled in 1968 that a stop is permissible only where the police have objective “reasonable suspicion” that crime may be underway, and that a frisk is permissible only where the police independently have “reasonable suspicion” that an individual is armed. In May, a federal judge in Manhattan granted class action status to a legal challenge brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights to the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program. The judge found, among other things, that in at least 170,000 stops between 2004 and 2009, the police officers’ stated reasons did not establish a constitutionally adequate basis for the stop, and that in half a million more recorded stops “officers listed no coherent suspected crime” whatever. The court also cited tape recordings of precinct meetings in which supervisors

can be heard repeatedly telling officers to conduct unlawful stops and arrests and explaining that the instructions for higher performance numbers are coming down the chain of command.4

Possibly in response to the lawsuit and related criticism, the number of stops dropped 34 percent in the second quarter of 2012. Still, the New York authorities make no apologies for the practice, and are appealing the court’s decision. Mayor Michael Bloomberg claims that the tactic has deterred people from carrying guns and saved lives, though there are no good data to support his claim. A gun has been recovered in only one of every one thousand stops—but supporters claim that this just shows that the program is working to deter people from carrying guns in the first place. Murder is down in New York, but as shown above, many other changes in policing might account for that. More to the point, shootings have continued at the same rate despite radically increased stops; there were 1,892 shootings in 2002, with about 100,000 stops; and 1,821 in 2011, with nearly 700,000 stops.5

The city’s drop in crime rates began years before the aggressive stop-and-frisk policy was instituted, so it cannot possibly be the principal cause of the decline. And as noted above, most American cities experienced a substantial fall in the crime rate from 1990–2000, without using New York’s stop-and-frisk policy. Without a doubt, something in New York policing has saved lives, but attributing that result to the stop-and-frisk policy in particular is political propaganda, not reliable social science.

Still, murders and incarceration are dramatically down in New York City, and it is important to note that both trends disproportionately benefit young black and Hispanic men, who are disproportionately represented among homicide victims and prisoners. If there were proof that the stop-and-frisk policy was the only or most effective way to make the city safer, this would pose a dilemma for those who seek both to defend the Constitution and to protect the most vulnerable among us. But there is no such proof. The jury is still out on what caused New York’s crime decline, but the claim that racially targeted policing was necessary to achieve it is unfounded.

4.

David Kennedy’s Don’t Shoot demonstrates that there are credible alternatives to aggressive discriminatory policing. Kennedy, a criminal justice professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, was one of the organizers of Operation Ceasefire, a program in Boston in the late 1990s that was associated with a 60 percent drop in youth homicides. Kennedy’s book tells the inside story of how this promising program was carried out in Boston and then reproduced in several other cities.

Operation Ceasefire is a fairly straightforward application of “focused deterrence,” based on the observation that a very small number of young men are responsible for a large amount of serious violent crime. The initiative seeks to disrupt patterns of violence by targeting those responsible with credible threats of harsh enforcement, coupled with generous offers of social support if they avoid violent behavior.

The approach concentrates on specific problems, such as gang violence or open-air drug markets. The police identify many of the most prominent offenders and work up cases against them. Then, rather than prosecuting them, they call them to a meeting, show them they could be prosecuted, and tell them that unless the shooting stops, or they close down their drug markets, they will be arrested, convicted, and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. At the same meeting, former offenders speak about escaping the cycle of crime and violence, and social service providers describe programs available to help them turn their lives around.

The results, as Kennedy reports them, are impressive. In Boston, there were forty-six homicide victims under twenty-five in 1995. Operation Ceasefire was started in May 1996, and that year there were twenty-six homicide victims in the same age range. In 1997 there were only fifteen. Other cities have had similar experiences after adopting this approach. In Minneapolis, there were forty-one murders in the summer of 1996, but only eight in the summer of 1997. In Stockton, California, the number of gang homicides fell from eighteen in 1997 to one in 1998. In Indianapolis there was a 34 percent reduction in total homicides, a 38 percent drop in gang homicides, and a 53 percent drop in gun assaults in the city’s most dangerous neighborhood. In High Point, North Carolina, gun homicides dropped from fourteen in 1998 to two in 1999. And in Portland, Oregon, murder was down 36 percent citywide and the number of victims aged twenty-four and under fell by 82 percent.

None of these results, however, has been proven to have been directly derived from Operation Ceasefire. The initiatives are difficult to assess. They are not standardized, and involve several agencies and community organizations, not all of which are always carefully monitored; the effects of the programs often cannot be disentangled from many other influences that may have contributed to declines in crime; and it is extremely difficult to identify a comparable control group so as to isolate the changes attributable to the intervention. That said, the track record summarized above is impressive.

Kennedy claims, in sometimes self-aggrandizing and evangelical tones, that he and his fellow organizers of the Boston program “were completely rewriting the scholar’s landscape on youth violence,” that it was an “entirely new way of operating,” and that “it went against everything almost everybody thought.” In his more modest moments, however, he concedes that “it wasn’t unprecedented” and “wasn’t in fact all that unusual. Working cops do this kind of thing.” In fact, the Boston Police Department had used a similar program, Operation Scrap Iron, in 1994, two years before Operation Ceasefire. He also admits that scholars had long written about the importance of targeted deterrence, peer group influence, and social norms in affecting criminal behavior. So it’s not clear how dramatically new and different Kennedy’s approach really is.

Still, the “focused deterrence” strategy provides a promising alternative to the kind of carpet-bombing approach taken by the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy. Under Kennedy’s scheme, the police act with much more precision, targeting individuals not for their race, ethnicity, or gender, but for their serious criminal conduct. Instead of stopping and frisking hundreds of thousands, several hundred are selected for investigation, meetings, threatened enforcement, and, equally important, assistance. As Kennedy puts it, the response is modeled on how we might treat a wrongdoer in our own family: “You’ve broken the rules, and I’m going to do something about it, and I love you and of course I will continue to care for you.”

Kennedy’s approach is more promising than stop-and-frisk, not only because it appears to be more narrowly focused, but also because it is less likely to generate widespread community resentment. Yale law professor Tom Tyler has shown that what makes people obey the law is their perception that the law and its enforcers are legitimate.6 Legitimacy turns in significant measure on procedural justice—the sense that one has been treated fairly and with respect. The law loses legitimacy when the police blanket a neighborhood with heavy-handed tactics, stop and frisk people without constitutional justification, target suspects based on race and ethnicity rather than conduct, and use laws as pretexts to arrest people for other offenses for which they lack probable cause. By contrast, the law’s legitimacy is likely to be reinforced when the state intervenes in a carefully thought-through manner, concentrates on the most egregious offenders, involves the community, and simultaneously threatens punishment for criminal behavior and offers assistance if that behavior is avoided.

Whether or not we can break the inexcusable NRA logjam on effective gun control legislation, recent history shows that local policing practices can make a significant difference in gun violence, especially in the inner city. And between New York’s sweeping stop-and-frisk policy and the carefully focused deterrence strategy that Kennedy advocates, the latter is surely a more hopeful—and lawful—response to the persistent problem of gun violence in America.

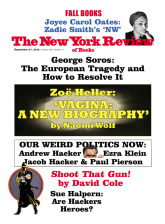

This Issue

September 27, 2012

Pride and Prejudice

Cards of Identity

Are Hackers Heroes?

- 1

-

2

Children’s Defense Fund, Protect Children, Not Guns, 2012. ↩

-

3

Center for Constitutional Rights, “2011 NYPD Stop-and-Frisk Statistics”. ↩

-

4

Floyd v. City of New York, No. 08 Civ. 1034, (S.D.N.Y. May 16, 2012). ↩

-

5

See Jeffrey Fagan and David Rudovsky, Letter to the Editor, “The Problems With Stop and Frisk,” The New York Times, June 13, 2012. ↩

-

6

See Tom R. Tyler, Why People Obey the Law (Princeton University Press, 2006). ↩