In response to:

Mr. Madison's Weird War from the June 21, 2012 issue

To the Editors:

Gordon S. Wood’s excellent article on the origins and impact of the War of 1812 [“Mr. Madison’s Weird War,” NYR, June 21] features an interesting omission. The British burning of the Capitol, White House, and other buildings in Washington, D.C., in August 1814 was a direct and proportional retaliation for the American looting and burning of the Legislative Assembly and other buildings in York, now Toronto, Ontario, in April 1813. This war was indeed the first time that the United States had invaded a sovereign, peaceful democracy in order to expand its territory or influence, but sadly, not the last. The American invasion succeeded in unifying the young Canada and ensured that the country would never join the United States.

One wonders if the wise Madison, in his private moments, worried about the implications of the trend he had inaugurated in American foreign policy. Such curious blindness to American acts of aggression, and the persistent belief that the United States is an exceptional nation, divinely blessed always to be the Good Guys, remains a serious impediment to winning “hearts and minds” worldwide. A more objective assessment of US history might lead to a more realistic relationship with other nations, friends and enemies both.

Gerald V. Denis

Boston University

Boston, Massachusetts

Gordon S. Wood replies:

Dr. Denis is correct in pointing out that prior to the British burning of the public buildings in Washington, American soldiers had looted and burned some buildings in York, and they had done so not once, but twice. This fact is well known to historians, if not to the general American public. But Upper Canada was not “a sovereign, peaceful democracy” as Denis contends. It was a hierarchically organized colony of the British monarchy whose officials, historian Alan Taylor claims, possessed a “garrison mentality” and with which the United States was at war. If the United States was to bring the war to the British on land, it necessarily had to invade Canada.

Moreover, contrary to what Denis says, the British burning of Washington was not “a direct and proportional retaliation” for American actions. The places were very different and the armies involved were very different. York was a small frontier town of about six hundred inhabitants while Washington had a substantial population of about 13,000. The American forces that attacked York were undisciplined ragtag soldiers who blatantly ignored their officers’ orders to avoid looting and burning. Indeed, so confusing and chaotic was the fighting along the fluid US–Canadian border and so common was the plundering and burning by both sides throughout the war that some British subjects actually came in from the countryside to join in the looting of their own capital.

By contrast, the British forces that burned Washington were highly disciplined soldiers completely under the control of their officers. Their burning of the American capital was much more deliberate, organized, and substantial. As George C. Daughan claims in his book, “Nothing the United States did in Canada…remotely justified the burning of Washington.”

Many Americans, as Denis claims, did see their invasion of Canada as a liberation of the Canadians from the hated British monarchy. If this war launched what Denis calls America’s subsequent “acts of aggression,” it was not a very auspicious beginning. It’s highly doubtful that an objective history of the War of 1812 is going to lead to the United States having “a more realistic relationship with other nations.”

Denis is right, however, when he says that the war created a new sense of Canadian nationhood, which is why the Canadians are celebrating the bicentennial of the War of 1812 much more fervently than Americans.

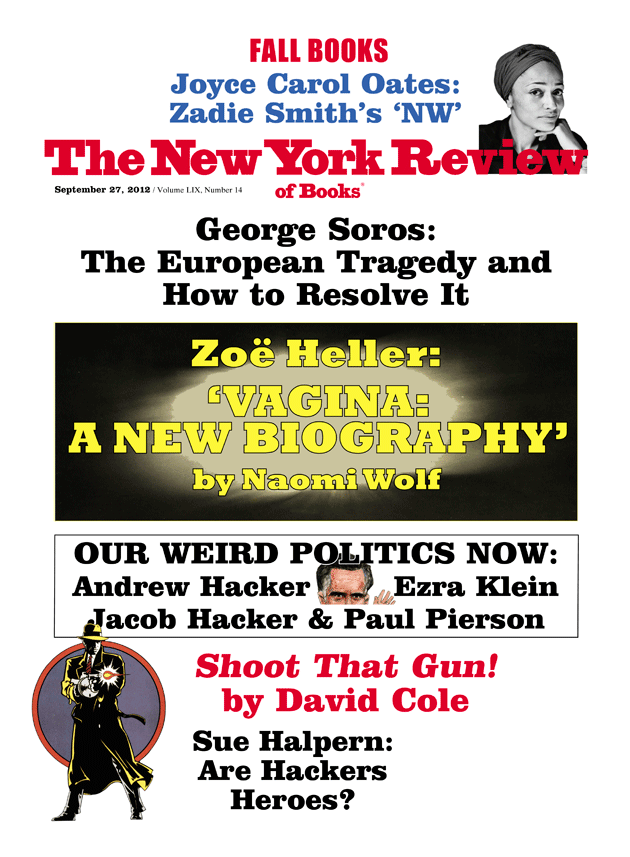

This Issue

September 27, 2012

Pride and Prejudice

Cards of Identity

Are Hackers Heroes?