Our political conventions have long since become TV shows with little suspense and an ever-expanding cast of media commentators functioning as a Greek chorus, telling us what to look for, what might or might not happen, how balefully the latest cycle of ambition and the duel for power is likely to turn out for the commonwealth. Though they tend to run as a herd, these toilers, reaching daily and hourly for fresh insights, save us from having to think for ourselves.

What fun there is in conventions is in their unanticipated moments—reinventions of the ritual, usually but not always scripted, that prove memorable. When Barack Obama landed in Charlotte to give his third big convention speech in eight years, he could expect to be compared both to the 2004 model Obama—a wiry, intense, out-of-nowhere state legislator with an arresting story and a gauzy vision—and to the 2008 model, the one in front of the styrofoam columns with his many promises of hope and change.

In Charlotte, none of that would be new; much of it would be considered shopworn. The Bank of America Stadium where he was first scheduled to speak, before thunderstorms threatened, would have evoked his quandary. It might as well have been called Bailout Park (after the Bush program Obama inherited along with some of the blame that attached to it in many minds, and an economy shedding jobs at a rate of 150,000 a week). Without a lot of attention paid to all he’d actually accomplished, he’d now nearly four years later been graded and stamped DISAPPOINTING, first by media consensus, then by his opponent, who, after months of snide remarks about the various ways in which this exotic creature failed to “understand” America—its enterprise and “exceptionalism”—simply embraced that more-in-sorrow verdict.

In Tampa, with a catch in his throat, Mitt Romney claimed to have nurtured a hope four years ago that Obama would succeed in mastering the worst financial crisis since the 1930s. Of course, Romney didn’t acknowledge the extreme lengths to which House and Senate Republicans went to ensure that Obama would do no such thing, resisting him with near unanimity on every major initiative touching on taxes and jobs, going so far last year as to risk another collapse by showing that they considered a federal default less risky and outrageous than an increase of the historically low tax rates on the upper one or two percent.

At moments like that, Obama often seemed to have been caught flatfooted by the gall of his opponents, unable to find plain language to do a Harry Truman and give ’em hell, irritated on occasion by the need to spell out obvious facts and knock down obvious distortions. His promise—that he held in his own person and temperament the ability to heal the partisan breach—was thus mocked and refuted at the outset by the barefaced resistance he confronted. The Republicans would do nothing to legitimize his leadership. Viewed as having lost control of “the narrative”—in the opinion, at least, of those locked into the nonstop “conversation”—the president needed to find a way in Charlotte, finally, to recapture it: to stand on his record without sounding defensive, to offer a believable future consistent with past promises. He needed to be memorable again.

As polls show, many voters are capable of holding two (or more) seemingly inconsistent thoughts in their minds: one that Obama has been an OK president (that’s to say, well-meaning, conscientious, trying to do what he thinks right for most Americans and the country’s future); another that the country is headed in the wrong direction. They’re capable of realizing, unlike some commentators, that a president doesn’t control everything that happens, that Obama was hardly the creator of the mess he inherited. If they like a president enough, they’ll overlook, or at least put aside, embarrassing episodes such as the Iran-contra scandal of the Reagan years or Bill Clinton’s office dalliance, but maybe not when the embarrassment is a stubbornly high unemployment rate and a seemingly endless foreclosure crisis.

Recent polls indicate that 50 percent of likely voters still think Romney might be a better steward of the economy. This could be a bet on competence rather than ideas, yet another example of Dr. Johnson’s “triumph of hope over experience.” Not a good bet, you might have thought, given Romney’s baggage: the Republican record of zealotry and intransigence, his offshore accounts and apparent limitations as a candidate, or his fixation on cutting taxes on businesses and “job creators” as the answer to joblessness and almost anything else. But if that’s Romney’s burden, the tightness of the race must say something about Obama’s load, about the dissatisfaction that the convention would need to address, suggesting it might not be sufficient to keep hammering Romney as an out-of-touch zillionaire if the president couldn’t answer the pointed question posed by Paul Ryan, in his otherwise meretricious Tampa speech, of how things might be different in a second Obama term.

Advertisement

First, someone needed to say what’s often left unsaid by pious souls accustomed to considering the good the enemy of the best: that even if this president is “not the second coming of FDR,” as Michael Grunwald concedes in a well-argued new book positively reassessing Obama’s earliest initiatives,* even if his attempts at soaring rhetoric don’t always soar, even if he cannot impersonate warmth, humility, or gratitude with the practiced aplomb and head nods of Ronald Reagan, or reach out to an audience on an emotional level with the unquenchable thirst of Bill Clinton, he has been, all in all, better than OK when it comes to the big choices, domestic as well as foreign—a better than average president in a terrible time—decisive, prudent, focused on results.

“Maddeningly pragmatic” was the way David Remnick summed him up last year. He denied himself and his most avid followers the satisfaction of a commission of inquiry into the interrogation transgressions of the Bush-Cheney years; resisted the temptation to take over Citibank when the financial system was tottering; never sent Congress his blueprint for health care—in order to get the CIA focused on al-Qaeda and the hunt for its leader; to raise capital requirements on the banks and get credit flowing without putting the world financial system through the wringer again; to bring home a piece of legislation that would pass Congress if not, while the debate roiled, the bar of liberal opinion. Less driven by polls, at pivotal moments, than any recent president, he gambled on going for broke on health care, against the advice of advisers, with the same single-mindedness with which he went after Osama bin Laden, bagging both with mixed results for himself politically. There was a huge swing to the Republicans in 2010 after the Affordable Care Act was finally pushed, tugged, and wriggled through an unruly Democratic Congress rightly fearful that it might be on its last legs, and a modest bounce after Osama’s demise.

A few hours before the convention’s first gavel, I dropped in on a luncheon forum (sponsored, I can’t avoid mentioning again, by the ubiquitous Bank of America) at which Connecticut’s Democratic governor, Dannel Malloy, was asked Ryan’s question: how a second Obama term would be different. The governor refrained from gushing. Tellingly, he said Obama was poised “to be a great second-term president.” That left a lot unsaid. By indirection, the phrase clearly implied he’d been something less in a first term that had taught him, the governor said, painful “lessons.” A Connecticut congressman, Joe Courtney, chimed in, spelling those lessons out. Republicans were “not to be trusted, not to be worked with.” Their president, their candidate, these Connecticut Democrats were hoping, would show from here on that he’d finally gotten over his “post-partisan” delusions.

In The New New Deal Grunwald, a Time correspondent, also doesn’t gush, but he plainly thinks Washington opinion-mongers have missed the story on Obama’s efforts to grapple with the slide, which the president-elect learned after the election was much worse than anyone yet understood. (With the economic forecasts all pointing down, down, down, Obama wryly asked an adviser days before the election whether it was too late to hand the crisis—and the race—to McCain.) Grunwald seeks to make a case that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed less than a month after Obama came to office without a single Republican vote in the House and only three in the Senate, deserves to be appreciated as the greatest legislative landmark in decades (at least till the Affordable Care Act came along). This was the oft- derided “stimulus,” which was oversold as an engine for job growth and undersold as an ambitious program to put the collapsing economy on a “new foundation” for the future.

In Obama’s view, halting the slide was a necessary but not sufficient aim. Of the $787 billion thrown at the problem in the form of tax cuts, budget support for states, and infrastructure projects, about $150 billion went to clean energy, computerizing the health care system, refurbishing schools, and basic research. It was 50 percent bigger in constant dollars than the entire New Deal, Grunwald asserts, and the biggest investment ever in each of these various fields. Though it was too small in the view of some economists on the left, it was too huge, ambitious, and multifaceted to be grasped; plenty big enough, however, to help inspire the Tea Party revolt.

Advertisement

Ever since, the Republicans have scorned it as “the failed stimulus,” and while most of the targeted bucks appear to have done the intended double duty as Keynesian support and basic investment, Obama never hit on a slogan that would counter the perception of ineffectual, scattershot waste or suggest the promise he’d baked into the act. It was change you could believe in, if it worked, but as the unemployment rate spiraled up in the months before all this spending reversed the trend, who knew or cared? Now, with the spigot turned off, teachers and cops whose jobs were saved in 2009 are being laid off by state governments in the tens of thousands, dragging down the recovery. It thus remains a hard sell, until individual programs are extracted from the unwieldy whole and held up as success stories.

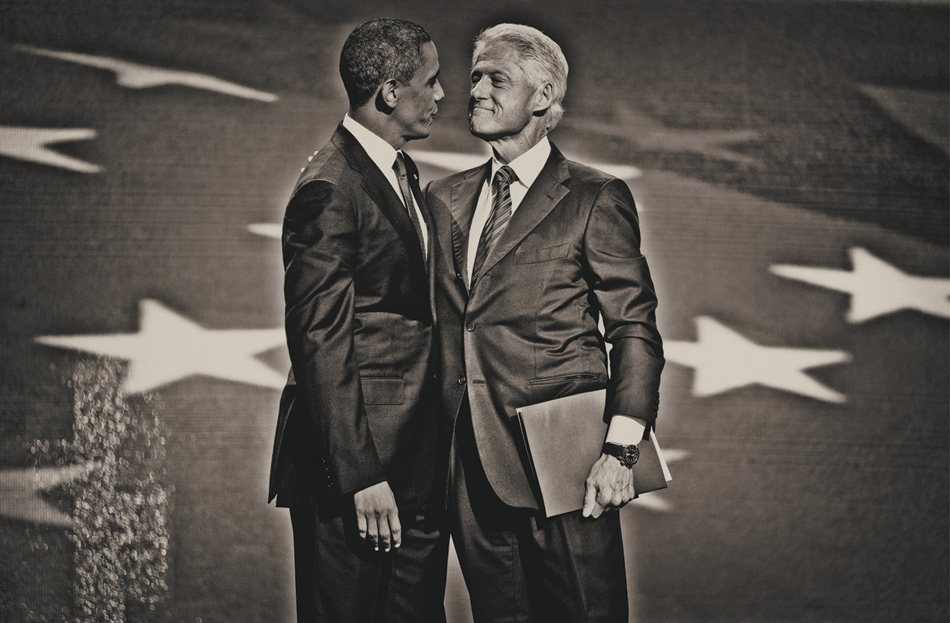

Franklin Roosevelt not being available, it was left to the New Democrat, deregulation advocate, forty-second president, and first husband in waiting to put across the argument that Obama had been brave and more effective than we knew in confronting the collapse. Considering the past bitterness, touchy reconciliation, and hopes for the future of the two presidents and their entourages, Bill Clinton’s appearance on the convention platform on its second night was an occasion of delicious irony as well as a coming together to bring a tear to any unabashed Democrat’s eye. Here was the stuff of dynasties, as if a threatened Tudor had turned to a Plantagenet for support.

Relishing the moment, the man from Hope turned in a boffo performance, laced with humor, good-natured mockery of the Republicans, and a tutorial for the president and his speechwriters on how to connect. Judging from their books, Obama is much the better writer, but on the stump he sometimes comes across as straining for the common touch—his repeated use of the word “folks” is the tip-off—and denies himself memorable lines. Where Clinton entertains and explains, Obama tends to sermonize and exhort.

His sense of destiny and cool self-sufficiency—that inwardness that comes across as disdain for the political game as Washington has known it—once offended the eternal striver in the former president. Four years ago, as his dreams of returning to the White House as a spouse faded, he was heard to refer sourly to Hillary Clinton’s successful challenger as “the Chosen One.” He didn’t mean the people’s choice. But standing in the arena where the Charlotte Bobcats play, the old performer neatly turned that perception into a song of praise. “I want to nominate a man who’s cool on the outside,” he said, “but who burns for America on the inside.”

This was a president, he said, who truly believed in cooperation, one who chose a former rival to be his vice-president, put Democrats who supported Hillary and Republicans in his cabinet. Then, with the warmest of smiles spreading across his no longer boyish countenance, a smile that conveyed bygones-be-bygones generosity and open self-delight, came the payoff. “Heck, he even appointed Hillary!”

Turning to the Republicans, he ad-libbed a line about their living in an “alternative universe,” and summed up their economic platform with a zinger: “We left him a total mess, he hasn’t cleaned it up fast enough, so fire him and put us back in.”

Read on a computer screen, his prepared text was a summary of standard Democratic talking points. He was not the first speaker of the evening, maybe the fifth, to mention the million jobs Obama is supposed to have saved when he bailed out the auto companies, or to make the case for health care reform. The magic was in the way he made it, his ability to read the audience in the hall, turning boilerplate into real communication with the larger viewing audience out in the land that had to be captured before it switched to ESPN or turned in for the night.

His text, scrolling up in white letters on a big screen where delegates who functioned as a studio audience could follow it, noted in a paragraph that two thirds of the Medicaid funds Republicans propose to slash by one third went to elders in nursing homes and middle-class families with children with Down’s syndrome or autism. “I don’t know how those families are going to deal with it,” the scrolling text cued. “We can’t let it happen.” It was instructive to see how he milked those lines.

As delivered, the talking points in that paragraph became five different applause lines; its final two sentences, spun out to five, were raised from talking points to urgent appeals that brought the delegates to their feet. “And, honestly, let’s think about it, if that happens, I don’t know what those families are going to do. So I know what I’m going to do. I’m going to do everything I can to see that it doesn’t happen. We can’t let it happen. We can’t!”

When Obama made a predictable surprise appearance on the platform after Clinton finally uttered his “God bless America,” their choreography was imperfect but entertaining. The incumbent president bowed slightly, the old one deeply. Then they clasped hands and embraced. Soon Obama’s hand was on Clinton’s back, seeking to steer him off stage. It wasn’t easily done.

It was a performance, for sure, but as they made their way out into the muggy night, veteran conventiongoers, hardened hacks, got to compare themselves to connoisseurs walking out of a recital by a great musician at the end of his career. By dawn’s early light, it seemed as evanescent as most convention oratory. Clinton, after all, was not the candidate.

His defense of Obama and needling of the Republicans had sounded comprehensive enough but there were subjects left untouched by him and most other speakers on the second night. One was the raid into Pakistan that killed Osama. That plainly was being saved for the finale. Another was the existence of poverty in the land. A leader of socially active American nuns now under a Vatican cloud, Sister Simone Campbell, got in a word. She spoke of children having to care for invalid parents and a family that couldn’t get food stamps (and how many more there’d be if Congressman Ryan’s budget were enacted).

On the second night, silence also covered our moneybag politics in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s shameless overreach in the Citizens United case, equating cash with speech. A convention, being among other things a fund-raising jamboree, replete with skyboxes and invitation-only, off-the-record lunches in hotel dining rooms, may not be the place to scold big donors. And William Jefferson Clinton, the former landlord of the Lincoln bedroom, may not have been the man.

Elizabeth Warren, the Harvard law professor now running for the Senate in Massachusetts, who preceded him with a fiery speech, might have been the woman had she not emerged as one of the year’s champion fund-raisers herself, raking in Hollywood dollars before stumbling over a report that she once advanced a dubious claim in a diversity survey to being part (an infinitesimal part) Cherokee. More a populist than a Cherokee, Warren was still ready to stick it to banks that, she said, “marshaled one of the biggest lobbying forces on earth” to do in her brainchild, the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. But in Charlotte, populists didn’t constitute a tribe.

President Obama has never been forgiven for a single reference in a television interview a couple of years ago to “fat cat bankers on Wall Street.” Because they feel unappreciated, old backers now sit on their checkbooks or contribute to Super PACs backing Romney, who already has a large cash advantage. No twenty-first-century Democrat would dare quote FDR’s acceptance speech at the 1936 convention in which he assailed “economic royalists” and warned against dictatorship of the “overprivileged.” The constraints are obvious. If you’re courting billionaires yourself, is it possible to denounce the Koch brothers and Sheldon Adelson for their outrageous exercise of what’s now, according to our highest court, their First Amendment right to spend without limit? In a single line on the convention’s final night, Joe Biden got off a glancing shot and it went unnoted. The future that Democrats imagine, he said, would “promote the private sector, not the privileged sector.”

Letting the Bush tax cuts on the wealthy expire—the key bone of contention—had to be defended as a matter of fairness, as “leveling the playing field” for an idealized middle class that only wants to live the “American dream” that their parents believed in. Not once did anyone cite statistics on widening income inequality over the past three decades, though they might have been germane to the argument. The hidden scriptwriters who carefully shaped the dramaturgy of the convention made sure in Charlotte that pieties about the “American dream” got repeated four or five times an hour, at least as often as in Tampa. It’s our civil religion, the notion that each generation gets to do better than the one before, whatever experience and statistics show. The point was to say that the “dream” was alive and well in Democratic hands, even though it was plainly fading in the real world before the housing bubble burst. Biden couldn’t say it was “morning in America” but he did the best he could. “America is coming back,” he declared.

On each lap of this relay, representatives from the party’s equivalent of central casting stepped forward to take the baton—women young and old, African-Americans, gays, and Hispanics, especially Hispanics in the best time slots, each telling the same story of struggle and dreams in slightly different words and accents. Designed less to persuade the unpersuaded in the great beyond, the convention was a kind of bellows positioned to ignite with this mighty expenditure of air the basic blocs on which Democrats were counting.

The star of the proceedings had been Michelle Obama, whose opening night speech recaptured much of the freshness and urgency her husband brought to the rostrum in 2004. By the time she reappeared there in the final hour to briefly introduce him, that part of the audience that hadn’t just tuned in had been immersed in encomia to his humanity, his identification with ordinary people, his achievements, his decisiveness. There was no room for “disappointment” in the wise and caring man who’d stood practically alone, it seemed, to halt the slide and end the wars. So now, as he stepped into the spotlights swirling around him and took in the cheers, Barack Obama was in competition not only with his 2004 and 2008 selves but with the idealized version the convention had been designed to reveal.

Once he started to speak, he came back into focus as the President Obama who has been there all along. He was cogent as he generally is, persuasive to anyone inclined to be persuaded, but not conspicuously fired up despite the chants of “fired up, ready to go” that had become a convention refrain. If this president ever shows anger and indignation, he does it in private. He’s stingy with humor too, having learned that there’s a price to pay for public displays of dry wit. But he had his moments, for instance when he inched up to the fraught subject of political money with more forthrightness than any previous speaker. “If you’re sick of hearing me ‘approve this message,’” he said winningly, “believe me—so am I.”

It was a theme to which he’d keep returning, in a speech built of one-liners on carefully interlaced themes rather than sustained policy arguments. “If you give up on the idea that your voice can make a difference,” he said, seeking to rally supporters of four years ago, “then other voices will fill the void: the lobbyists and special interests; the people with the $10 million checks who are trying to buy this election, and those who are making it harder for you to vote.” And he promised to oppose “another $4 billion in corporate welfare” for oil companies.

Citizens United was never mentioned, nor the Supreme Court, which had as he once said “opened the floodgates.” It would tip even further to the right if Obama went down. In a broader sense, he alluded to all that when he urged viewers out there in the land: “If you reject the idea that our government is forever beholden to the highest bidder, you need to stand up in this election.” Not being the sort of leader who makes a habit of fighting battles he can’t win, he didn’t say how he proposed to stanch all the beholdening that goes on in the eternal battle for influence. Wall Street was mentioned but not blamed for the financial crisis. He simply vowed that it wouldn’t get its hands on Social Security.

The speech was designed as an overture to the fall campaign. Perhaps his edgier phrases would be developed into themes as Obama and other Democrats felt the brunt of the attack ads coming their way. In prime time, there were few hints of how he’d handle the struggle over Obamacare, which still polls poorly in states he needs. He never mentioned the Affordable Care Act by name. Instead, alluding to it obliquely, he told of “a little girl with a heart disorder in Phoenix who’ll get the surgery she needs because an insurance company can’t limit her coverage.” The policy of the other side, he suggested, was simply, “hope that you don’t get sick” if you can’t afford insurance.

Bill Clinton stayed on the point longer, offering more specifics, than the president who brought home the reform. “Soon,” he said, “the insurance companies, not the government, will have millions of new customers, many of them middle-class people with pre-existing conditions. And for the last two years, health care spending has grown under 4 percent for the first time in fifty years.” By the weekend Romney, who has pledged to repeal Obamacare as his first initiative, was saying he’d save the provisions that have already taken effect such as the one Clinton highlighted on preexisting conditions.

Maybe there was a lesson here. Repeal would still be one of the main consequences of an Obama defeat. How forcefully the Obama campaign will try to make that case is another matter. Will it follow the polls or, as happened when the president opted for the reform in the first place, fight what might become a losing battle? Will it take the offense and try to tell people what they stand to lose when mostly they don’t even know what they stand to gain? Not an easy choice.

As the one-liners accrued, the presentation turned personal. “While I’m very proud of what we’ve achieved together, I’m far more mindful of my own failings,” he said, going on to quote Lincoln. The quotation was apt and affecting, but the implied comparison of himself to the sixteenth president may have undermined what was meant as a display of humility. Moments later, still trying to reignite the movement he imagined himself to have led four years ago, he said: “We draw strength from our victories, and we learn from our mistakes.”

That “our” came across as an uncertain note, ambiguous in its meaning. Were the unspecified “mistakes” first-person plural or first-person singular? Had his supporters not been there for him when he needed them, as in the 2010 congressional elections? Or had he failed to communicate his need? Now they had to understand that the road would be longer and harder than they may have thought. He never had promised, he now said, that it would be “quick or easy.”

I tried to think of a winning candidate who promised a harder path. All that came to mind were losers: Adlai Stevenson’s “Let’s talk sense to the American people” a full sixty years ago and Walter Mondale’s candor about a tax hike.

Still, if erstwhile Obama followers were looking for an apology for overpromising on his part, they could find it there. They could also conclude that he’d been deepened by his time in the White House. In either case, his more urgent message was that the election was “a choice between two fundamentally different visions for the future.”

It’s also a choice between two fundamentally different views of Barack Obama. If he loses and his most significant initiatives are undone, his tenure may receive assessments even more mixed than it has gotten until now. If he wins, he’ll automatically be seen as a consequential president for reasons beyond the once-stunning fact of his color. Health care, the clean energy programs, and all the other reforms won’t be rolled back.

What the acceptance speech didn’t do was answer the Ryan question: How would the next four years be different? It didn’t do that in part because the answer so obviously hinges on the outcome of the congressional races. If Republicans retain the House and a blocking vote in the Senate with its archaic structure and rules—or win a majority there—it’s hard to see how the gridlock of which Obama complained might be eased.

Conceivably, such a prospect could serve as a spur for a Trumanesque attack on “Do Nothing” Republicans in Congress. But there seems to be a consensus among tacticians that a partisan plea from the head of the ticket to turn out the 2010 class of Tea Party Republicans could alienate independents. All politics being local, the president who once tried to hold himself above party will probably never go so far as to ask voters to give him a Democratic Congress again. The pledge to support Obama will have to be put across by local candidates where it may do some good, which isn’t everywhere.

In recent interviews, the president has been reduced to the wan hope that Republicans would read his reelection as a message from the American people “to get things done,” once “Mitch McConnell’s imperative of making me a one-term president is no longer relevant.” In Charlotte, he said he stood ready to reform the tax code and try again to negotiate a “grand bargain” on the basis of the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles commission’s report. What he couldn’t promise this time was that his victory would serve up the elixir to make the bargain go down.

“No party has a monopoly on wisdom,” he said, possibly for the thousandth time. In 2008 he seemed confident that he in his own person could transcend partisanship. Now he was saying the country must do it—a stirring call that left the Ryan question hanging.

—September 13, 2012

-

*

Michael Grunwald, The New New Deal: The Hidden Story of Change in the Obama Era (Simon and Schuster, 2012). ↩