1.

The great poet Matsuo Basho, traveling in the northeast of Japan in 1689, was so overcome by the beauty of the island of Matsushima that he could only express his near speechlessness in what became one of his most famous haiku:

Matsushima ah!

A-ah, Matsushima, ah!

Matsushima ah!

Matsushima, known since the seventeenth century as one of Japan’s “Three Great Views,” is actually an archipelago of more than 250 tiny islands sprouting fine pine trees, like elegant little rock gardens arranged pleasingly in a Pacific Ocean bay. Because these islands functioned as a barrier to the tsunami that hit the northeastern coast with such horrifying consequences on March 11, 2011, relatively little damage was done to this scenic spot. Just a few miles up or down the coast, however, entire towns and villages, with most of their inhabitants, were washed away into the sea. 2,800 people are still missing.

I decided to go on a little trip to Matsushima this summer because I had never seen this particular “Great View,” even though I had in fact been there once before, in 1975. Then, too, I set out from the harbor in a boat filled with fellow tourists—all from Japan. As we took a leisurely cruise into the bay, a charming guide gave us a running commentary on the islands we were supposed to be gazing at, their peculiar shapes, names, and histories. The problem was that no matter how keenly we craned our necks in the directions indicated by the guide, we could not see a thing; we were in the midst of a thick fog. But this did not stop the guide from pointing out the many beauties, or us from peering into the milky void.

It was a puzzling experience. My familiarity with Japan was still limited. I didn’t quite know how to interpret this charade. Why were we pretending to see something we couldn’t? What did the guide think she was doing? Was this an illustration of the famous dichotomy that guidebooks say is typical of the Japanese character, between honne and tatemae, private desires and the public façade, official reality and personal feelings? Or was it the rigidity of a system that could not be diverted once it was set in motion? Or was the tourists’ pretense just a polite way of showing respect to a guide doing her job?

I still don’t really know. But since then I have seen other instances of Japanese conforming in public to views of reality that they must have known perfectly well were false, to protect “public order,” or to “save face.” Japan is a country where the emperor is rarely seen naked.

2.

One thing revived by the “3/11” earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster is the culture of protest, which had been pretty much moribund since the great anti–Vietnam War and antipollution demonstrations of the 1960s. In his new collection of essays, Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering, John Dower describes these 1960s protests as a “radical anti-imperialist critique [added] to the discourse on peace and democracy.” There hasn’t been much of that in Japan of late.

But now, since the nuclear meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi reactors, thousands of protesters gather in front of Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko’s Tokyo residence every Friday demanding an end to nuclear power plants. Even larger gatherings of up to 200,000 people have been demonstrating in Tokyo’s central Yoyogi Park, as part of the “10 Million People’s Action to Say Goodbye to Nuclear Power Plants.” Eight million have already signed. This has had at least some cosmetic effect. First the government announced that nuclear energy would be phased out by 2040. This has been softened since to the promise that this plan would at least be considered.

The atmosphere at the demos is not unlike that of last year’s Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in the US: passionate, peaceful, festive, and sprinkled with an element of nostalgia by the conspicious presence of veterans of the 1960s. One of the leading figures is the novelist and Nobel Prize laureate Oe Kenzaburo, aged seventy-seven.

Oe is keen to draw parallels between 3/11 and the past, though not with the protests in the 1960s, when petrochemical and mining companies were spewing their poison onto the land. Rather, he recalls 1945, when the Japanese became the first victims of atomic bombs. Oe sees modern Japanese history, and its nuclear disasters, through the “prism” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: “To repeat the error by exhibiting, through the construction of nuclear reactors, the same disrespect for human life is the worst possible betrayal of the memory of Hiroshima’s victims.”1

Other Japanese have heard different echoes from the last world war. The ninety-four-year-old writer Ito Keiichi, for instance, was moved by the spirit of self-sacrifice he observed in the firefighters, soldiers, and nuclear plant workers who had tried, often at considerable personal risk, to contain the damage at the stricken nuclear reactors. They reminded him of the self-sacrificial sense of duty displayed by Japanese soldiers and civilians during the war. This is not a sentiment that many Chinese, who saw the Japanese military spirit at first hand, might readily share, but in Japan it still has a certain resonance. The authors of the slight but very useful book Strong in the Rain, David McNeill and Lucy Birmingham, report that Japanese TV commentators sometimes compared the heroes of Fukushima to kamikaze pilots.

Advertisement

I cannot imagine Oe’s eyes moistening at the thought of kamikaze pilots, but his focus on Hiroshima, like Ito’s sentiments about wartime Japanese sacrifices, might fit something John Dower identifies as a common trait in Japan, something he translates as “victim consciousness,” or higaisha ishiki. What is meant is the tendency to focus on the suffering of Japanese, especially at the hands of foreigners, while conveniently forgetting the suffering inflicted by Japanese on others.

It is certainly true, as Dower says, that most Japanese associate the war with Hiroshima, and not, say, with the Rape of Nanking, the Bataan Death March, or the brutal sacking of Manila. Yet Oe’s sentiments, and those of his fellow anti-nuclear protesters, cannot be reduced to “victim consciousness.” National self-pity is not at the core of their protest. Their point is, rather, that both Hiroshima and Fukushima were man-made disasters. And their rage is fueled by a long history of government deceit, of being consistently lied to, specifically about nuclear power; it has to do with being made to conform to official views of reality that have turned out to be patently false.

Doctoring reality for propaganda purposes is not only a Japanese practice, of course. News of the terrible consequences of the atom bomb attacks on Japan was deliberately withheld from the Japanese public by US military censors during the Allied occupation—even as they sought to teach the benighted natives the virtues of a free press. Casualty statistics were suppressed. Film shot by Japanese cameramen in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings was confiscated. Hiroshima, the famous account written by John Hersey for The New Yorker, had a huge impact in the US, but was banned in Japan. As Dower says: “In the localities themselves, suffering was compounded not merely by the unprecedented nature of the catastrophe…but also by the fact that public struggle with this traumatic experience was not permitted.”

But Dower also points out another consequence of the wartime destruction of Japan: an almost religious faith in science to get Japan back on its feet again, or even, just before the war was finally over, to allow it to retaliate. This included the misguided hope that Japan might have its own bomb. One of the most famous documents written by a Hiroshima survivor is Dr. Hachiya Michihiko’s Hiroshima Diary, which could only be published in the 1950s, after the occupation was over. Dr. Hachiya describes scenes in a hospital only days after the bombing. Horribly mangled and mutilated patients are dying of diseases that were barely understood. A rumor spreads that Japan has attacked California with the same kind of bomb that struck Hiroshima. There is jubilation in the ward.

What put paid to any celebration of nuclear power in Japan, however, was the American H-bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954. By a slice of ghastly irony, the only victims of this explosion in the Pacific were Japanese fishermen, whose boat had strayed too close. This inspired the first Godzilla movie, reflecting widespread Japanese fears of a nuclear apocalypse. And it was the beginning of the anti-nuclear movement. As Dower points out, the Japan Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was not just supported by the left in Japan, but in its early stages by the conservative parties too.

It was also during the 1950s, however, that some Japanese conservative politicians began to push for nuclear energy. Oe singles out for particular opprobrium the right-wing nationalist and later prime minister Nakasone Yasuhiro and the conservative newspaper tycoon Shoriki Matsutaro. Shoriki is still known as the grand old man of postwar Japanese baseball and the “father of nuclear power.” He was not a prepossessing figure. Classified after the war as a “Class-A” war criminal, Shoriki was also blamed for massacres of Koreans in Tokyo when he was a police official in the 1920s. Strongly pro-American after the war, possibly working with the CIA, he was responsible for importing US nuclear technology to Japan. The first reactors were built in the 1960s by the General Electric Company. Before the 2011 earthquake, about 30 percent of Japanese electricity was generated by nuclear energy.

Advertisement

This is not much compared to France, where the figure is closer to 70 percent. But in the minds of Oe and other Japanese leftists, protest against Japanese nuclear policy is more than a matter of ecology. Given the political history of such figures as Shoriki and Nakasone, and their ties to the US, it is precisely the “anti-imperialist critique [added] to the discourse on peace and democracy” described by Dower that motivates some of the protesters. In Oe’s words: “The structure of the Japan in which we now live was set [in the mid-1950s] and has continued ever since. It is this that led to the big tragedy” of Fukushima in March 2011.2

There is a lot of truth to this. But the building of nuclear power plants in Japan, in some places very near lethal seismic faultlines, cannot be blamed only on a few right-wing conspirators with shady wartime pasts. Despite the early protests, most Japanese ended up supporting nuclear energy, partly perhaps because of the common faith in science, partly because it seemed like the best option in an archipelago critically short of natural resources.

Still, Oe is certainly correct to point his finger at the structure of Japan. A much too cozy relationship between government bureaucrats, national and local politicians, and big business allowed the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) to monopolize energy in large areas of Japan, including the northeastern coast where the disaster struck. This also entailed a virtual monopoly on the truth: nuclear power was good, the reactors were safe, there was nothing to worry about—even when, as happened several times in the 1970s, 1980s, and after an earthquake in 2007, pipes were leaking radioactive steam, safety regulations were ignored, and fires broke out.

TEPCO’s monopoly was not brutally enforced. It was more a matter of soft power. The acquiescence of local communities was bought with corporate largesse lavished on schools, sports fields, and other amenities. Research chairs at top universities were funded by TEPCO. Vast advertizing budgets were spent on the national media. Journalists and academics were asked (and presumably well paid) to act as consultants. But venality is not the only or perhaps even the most significant way by which the Japanese establishment is co-opted.

The largest mainstream newspaper companies, despite some differences in political tone, can be depended on to echo a kind of national consensus established by the same web of government and business interests of which the mainstream press forms an integral part. This is also true of the national broadcasting company, NHK, which is often compared to the BBC, but has none of its feisty independence.

The so-called “kisha [press] club system,” where specialist reporters from the major national papers are allowed exclusive access to particular politicians or government agencies, on the understanding that these powerful sources will never be discomfited by scoops, unauthorized reports, or special investigations, breeds a kind of journalistic conformity that is hardly unknown in more freewheeling democracies (think of the aftermath of September 11) but is institutionalized in Japan. The mainstream press does not really compete for news. What it does much too often instead is faithfully reflect the official version of reality. One reason for this is quite traditional. In Japanese history, as in China or Korea, the intelligentsia—scholar-officials, writers, teachers—were frequently servants rather than critics of power.

Not all the press in Japan is mainstream, of course. And there are mavericks, naysayers, and whistleblowers in Japan too. Unlike in China, they don’t disappear into the maw of a political gulag, but are marginalized in other ways. In their book, McNeill and Birmingham point out various instances of how this works. During the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, NHK never included a critic of nuclear energy in its exhaustive daily broadcasts. Even the commercial television channel Fuji TV no longer invited an expert back after he let slip, quite accurately, that there was danger of a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi reactors.

This expert, named Fujita Yuko, had committed the cardinal sin of bucking the official consensus that the public should be reassured that everything would be fine. Already long before the 2011 disaster, academic critics of the nuclear consensus were demoted or otherwise pushed aside. Between 2002 and 2006 severe safety risks had actually been reported at the Fukushima plant by several people, including company employees. These whistleblowers, in Birmingham and McNeill’s words, “bypassed both TEPCO and Japan’s Nuclear and Industry Safety Agency (NISA), the main regulatory body, because they feared being fired. The information was ignored.” According to the former governor of Fukushima prefecture, the informants were treated like “state enemies.”

Again, none of this is unknown in other countries. It is just harder in an insular, well-ordered society, where everyone should know their place, and the comforts and perks of conformity are considerable, to crack the façade of official truth.

3.

John Dower quite rightly stresses the brilliance of Japanese wartime propaganda. Everyone, from popular cartoonists to kimono designers, from the best filmmakers to the most respected university professors, was mobilized behind the war effort. When Frank Capra, to prepare for his own propaganda films in Hollywood, was shown Japanese movies made in the 1930s during the war in China, he said: “We can’t beat this kind of thing…. We make a film like that maybe once in a decade.” The official truth behind the Japanese war was not aggressively racist, as in Nazi Germany, or even imbued with the fascist love of violence. What Japan was supposedly fighting for was the liberation of Asia from Western imperialism and capitalism. Japan represented a new Asian modernity, based on justice and equality. Even many leftwing Japanese intellectuals were able to subscribe to this.

There were dissidents, even in those days. Many of them were Communists, who spent the war in jail. And some writers with well-established reputations could afford to retreat into “inner emigration.” But on the whole, writers, journalists, academics, and artists conformed. This was sometimes enforced, not least by the sinister “Thought Police” who were always ready to pounce on domestic critics. But oppression in wartime Japan was not as heavy-handed and violent as it was in Germany. It didn’t have to be. Exile, unlike in Germany, was not really an option for most Japanese; few had either the contacts or the language ability. The thought of being excluded, or driven to the margins of society, was threatening enough for most people to rally around the national cause. The intricate social web of press clubs, advisory committees, state-sponsored arts and academic institutions, and mutually helpful bureaucrats, soldiers, businessmen, and politicians was flexible and inviting enough to co-opt even many of those who were privately skeptical about the Japanese war.

A typical case was that of Mori Shogo, a respected member of the editorial board at the Mainichi newspaper during the war. The Mainichi is still one of the three major news organizations. (The others are the liberal-leaning Asahi and the more conservative Yomiuri.) Mori was not a dissident, but a patriot who was devastated by the Japanese wartime defeat. During the war, he conformed to the official truth: Japan was liberating Asia, military defeats were really victories, and so on. What is fascinating about the diary he kept in the immediate aftermath of the war is the sudden spark of independent thinking.3

Mori complains about the hypocrisy of American press censorship during the occupation: “We newspaper men had a difficult time during the war, when we were fettered by the militarists and the bureaucrats. Now, under the occupation of the US army, we can expect another period of hardship.” But the problems were not just those imposed by General MacArthur’s “Department of Civil Information” (a misnomer, if there ever was one). Mori describes a meeting, in the fall of 1945, of senior Mainichi editors to discuss the “press club system.” Should this comfortable cartel of the major media, mutually agreeing on what news to report, be continued, or should the papers begin to compete in a free market of news and ideas? Mori favored the latter option. But he was in a minority. The old system continued.

And so it was that in the spring of 2011, after the worst natural calamity to hit Japan since the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, or, to go along with Oe Kenzaburo, the worst man-made disaster since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese mainstream press decided to stick together and pass on the official truth, given out by government officials and TEPCO executives, that there was no danger of a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi plant. Not only that, but reporters from the major newspapers and broadcasters retreated together, like a disciplined army, from the worst stricken areas after the first hydrogen explosion in Fukushima Daiichi on March 12. The official reason was that their companies would not allow them to take risks. David McNeill, who was there, mentions Japanese who had other explanations.

An emeritus professor from Kobe College, Uchida Tatsuru, gave the Asahi newspaper his take on the journalistic retreat. There had been no attempt to investigate the disaster zone, because the main papers were afraid to compete, to do anything different from the others. He claimed that this reminded some readers of the war, when the media consistently published complete fabrications about Japan’s disastrous military operations.

One of the heroes in the Fukushima story is Sakurai Katsunobu, mayor of Minamisoma, a town fifteen miles from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. He complained to Japanese journalists that “the foreign media and freelancers came in droves to report what happened. What about you?” Cut off from information and essential food and medical supplies, he felt that his town was being abandoned. Out of desperation he turned to something that would not have been possible in previous crises. On March 24, Mayor Sakurai put a camcorded message on YouTube, with English subtitles, begging for help: “We’re not getting enough information from the government and Tokyo Electric Power Co.” He asked journalists and helpers to come to his town, where people were faced with starvation.

The video “went viral.” Sakurai became an international celebrity. Aid poured in from all over the world. And foreign as well as freelance Japanese reporters did come.

Birmingham and McNeill mention one Japanese freelancer, named Teddy Jimbo, founder of an Internet broadcaster called Video News Network. His television images from the earthquake zone were seen by almost a million people on YouTube. Meanwhile, NHK was still sending out reassuring messages on national TV, backed by a nuclear expert from Tokyo University named Sekimura Naoto, who told viewers that a major radioactive disaster was “unlikely” just before an explosion at one of the reactors caused a serious nuclear spill.

Sekimura is also an energy consultant to the Japanese government. Later, much too late, NHK and other broadcasters finally bought some of Jimbo’s footage. In his words, quoted by Birmingham and McNeill:

For freelance journalists, it’s not hard to beat the big companies because you quickly learn where their line is…. As a journalist I needed to go in and find out what was happening. Any real journalist would want to do that.

No less than in China or Iran, the Internet has proved to be a vital forum for dissident voices in Japan. Another, older source of critical views is the varied world of the weekly magazines, some serious, and some sensational entertainment. The weeklies came into their own after World War II as an alternative to the major media, even though some of them are actually published by the big newspapers. And they do not mince their words. One journal, the Shukan Shincho, called the TEPCO executives “war criminals.”4 But even the magazines can quickly run into the limits of what is permissible. AERA, a weekly magazine published by the Asahi, had a masked nuclear worker on the cover of its issue dated March 19, 2011, with the headline “Radiation Is Coming to Tokyo.” Even though, as Birmingham and McNeill point out, this was not untrue, the magazine was deemed to have gone too far. An apology was published and one of the columnists fired.

So there are gaps in the official truth of Japan. One of the unintended consequences of the 3/11 catastrophe has been the widening of these gaps. Fewer people believe what they are told. Cynicism toward officially sponsored experts has grown. Some see this as a problem. In March, Bungei Shunju, a prominent political journal, published an anniversary issue of the earthquake. One hundred well-known writers were asked to comment on 3/11. One of them, the novelist Murakami Ryu, lamented the lack of trust that resulted from the disaster, trust in government and the energy industry. It would take years, he said, to regain the trust of the Japanese people. Murakami is sixty, and enjoys a reputation for being cool, even a bit of a bad boy.

Nosaka Akiyuki, one of the best postwar Japanese novelists, was born in 1930, a survivor of the bombing raids in World War II.5 He had a rather different view of the question of trust. Reflecting on the official penchant for hortatory slogans (“Japan, do your best!” “United we stand!”), he advised the younger generation to think for itself: “Don’t get carried away by fine words. Be skeptical about everything, and then carry on.”6

And yes, I did see the islands of Matsushima the second time around. The skies were clear. I listened to the guide explaining the splendid sights. The tourists around me didn’t seem to be paying much attention to what she said. Well, well, I thought, Japan has changed. Then I realized they were all Chinese.

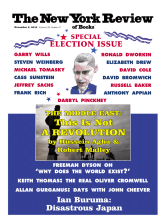

This Issue

November 8, 2012

What Can You Really Know?

John Cheever Turns 100

-

1

“History Repeats,” The New Yorker, March 28, 2011. ↩

-

2

“Japan Gov’t Media Colluded on Nuclear: Nobel Winner,” AFP, July 12, 2012. ↩

-

3

Mori Shogo: Aru Janaristo no Haisen Nikki (The Postwar Diary of a Journalist) (Tokyo: Yumani Shobo, 1965). ↩

-

4

Quoted by David McNeill in a forthcoming academic paper, “Them Versus Us: Japanese and International Reporting of the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis.” ↩

-

5

His masterpiece, The Pornographers, translated by Michael Gallagher (Knopf, 1968), deserves another attempt at English translation. ↩

-

6

Bungei Shunju, March 2012. ↩