Well, anyway, here is Pearl. And I, personally, believe it will stack up with Stendhal’s Waterloo or Tolstoy’s Austerlitz. That was what I was aiming at, and wanted it to do, and I think it does it. If you dont [sic] think it does, send it back and I’ll re-rewrite it. Good isnt [sic] enough, not for me, anyway; good is only middling fair. We must remember people will be reading this book a couple hundred years after I’m dead, and that the Scribner’s first edition will be worth its weight in gold by then. We mustnt [sic] ever forget that.

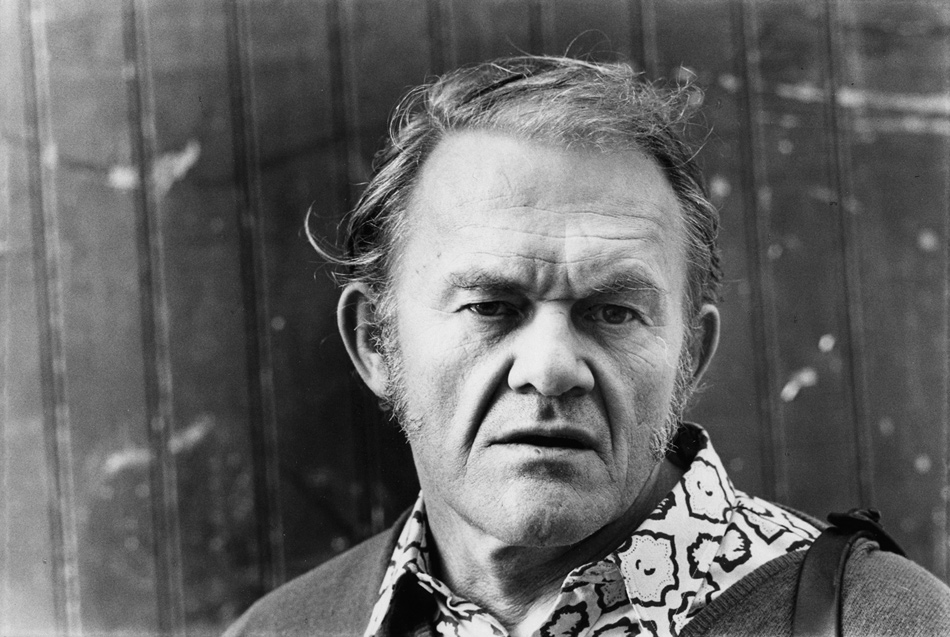

This is James Jones on October 30, 1949, a week before he turned twenty-eight, sending off to his editor, Burroughs Mitchell of Scribner’s, the climactic section of From Here to Eternity—his account of the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor that brought America into World War II. It’s also an announcement to the world, as it were, of his bold ambitions and his extravagant estimation of his talents. And it’s also a fair reflection of his state of mind at this turning point in his life. He knows he’s special; he’s excited about his achievement; his goals are daringly elevated; he’s prepared to work on and on to get where he feels he can go—where he must go. And he’s touchingly naive, at least he seems so to us now: Could any young, absolutely unknown writer make such assertions today? Would anyone take him seriously if he did?

But this was a different world, and young writers were still alive to the myth of the Great American Novel, to the recent histories of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and in Jones’s case, Thomas Wolfe—his favorite of all novelists. When he was nineteen, in Hawaii, he wrote about Wolfe to his brother, “In my opinion, little as it’s worth, he is the greatest writer that has lived, Shakespeare included. He is a genius. That is the only way to describe him.” (A lot of adolescent boys and young men in the 1930s and 1940s felt that way about Wolfe—I remember my own rush of awe and recognition when I came upon Look Homeward Angel at the age of thirteen or fourteen: this was writing.)

But when Jones came to start writing seriously, he didn’t sound like Wolfe at all. Of course, like Wolfe, he was caught up in his own feelings and experiences, but he was looking outward as well as homeward. He had been there in the army at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and what he wanted to tell the world was what it was like when the Zeros swooped out of the sky and began bombing and strafing, not how he felt about it. There’s nothing lyrical or poetical about the prose; it’s staccato, the talk is tough, direct, believable. First Sergeant Milt Warden (Burt Lancaster in the movie) is organizing his men just after the first wave of planes has come in over Schofield Barracks:

“The CQ will unlock the rifle racks and every man get his rifle and hang onto it. But stay inside at your bunks. This aint no maneuvers. You go runnin around outside you’ll get your ass shot off….

“Stay off the porches. Stay inside. I’m making each squad leader responsible to keep his men inside. If you have to use a rifle butt to do it, thats okay too.”

There was a mutter of indignant protest….

“What if the fuckers bomb us?” somebody hollered.

“If you hear a bomb coming, you’re free to take off for the brush,” Warden said. “But not unless you do. I dont think they will. If they was going to bomb us, they would of started with it already. They probly concentratin all their bombs on the Air Corps and Pearl Harbor.”

There was another indignant chorus.

“Yeah,” somebody hollered, “but what if they aint?”

“Then you’re shit out of luck,” Warden said.

This is pure Jones soldier-speak, remembered with what appears to be absolute accuracy almost eight years after the event. Alas, just a few pages later we get a touch of pure Jones artiness: “‘Thats my orders, Sergeant,’ Malleaux said irrefragably.” Instead of fighting Jones over dirty words—eventually compromising on the number of “fucks” and “cunts”—it’s at “fragably” where Burroughs Mitchell should have put his foot down. He should also have done something about Jones’s writerly tics—like his unrelenting repetition of “grinned” and “grinning.” (On one page alone, Prewitt grins six times.)

From Here to Eternity, as has often been noted, is a peacetime novel—“Pearl” happens only toward the end. It’s a soldier novel. It’s about men and women, about the idea of manhood. It’s about authority and rebellion. It’s about realists and idealists: Warden is the tough, capable, clear-sighted cynic who knows everything and runs everything but has a soft spot for the romantic yet unyielding Prewitt (Montgomery Clift), who is doomed by his refusal—his inability—to accommodate himself to the way things work and the way things are; Prewitt is also an artist—one of the army’s finest buglers (he once played “Taps” at Arlington) as well as a renowned boxer who enrages his commanding officer by refusing to fight for the company, having unwittingly blinded an opponent. Nothing can shake him, and he’s going to suffer and die rather than meet authority halfway.

Advertisement

Prewitt falls in love with an elegant whore who’s saving up to go home and make a classy marriage; Warden falls in love with the captain’s unhappy and mistreated wife. The two men appear to be entirely different, but finally they are ruled by the same inner compass—an insistence on untrammeled independence. Prewitt goes to the fearsome stockade rather than give way to his savage violence as a boxer. Warden can only marry Karen Holmes by becoming an officer, and at first he succumbs:

She could make him do anything now, even become an officer, now that she was sure he did love her. He was no longer a free agent, and as a result the old wild terrible strength that had been the power and pride of Milt Warden was gone.

It’s Samson and Delilah. But finally he can’t bring himself to do it—his hatred and scorn for the officer class prevail over his love for the only woman he has ever really cared for.

The need to prove oneself a man; the destructive trap of the Virgin Mother—“They had you by the balls from the minute you were bornd”; the pride in being a true soldier; the realization of life’s “unbelievable cruelty, its inconceivable injustice, its incredible pointlessness.” These are among the basic issues of From Here to Eternity, and they’re mulled over in endless interior monologues and bull sessions—embarrassing soul-searchings and strivings for profundity that are strikingly similar to many passages that mar Steinbeck. The two writers are a score or so years apart in age, but when they get thinky, they could be sophomores in the same class.

They also share a talent for brilliant observation. The Grapes of Wrath, when it isn’t swollen with meaning, is an extraordinary piece of reportage. Jones’s novel, too, is crammed with masterly scenes from life. Always you feel that he knows what he’s talking about, whether it’s the savagery of the stockade, life in a rough whorehouse, the anguish of love, or the most mundane minutiae like a “can of milk with its top sliced open by a cleaver butt. The thick white, dripping out past the congealed yellow of past pourings that had almost sealed the gash….”

The war had been over for just under six years when From Here to Eternity appeared, and even more than Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, published three years earlier, the public devoured it as a revelatory portrayal of the military life. There had been a tremendous publicity buildup before publication, and when the book was released, in February 1951, the critical reception was for the most part wildly enthusiastic. The cover of The New York Times Book Review, for instance, announced: “Make no mistake about it, From Here to Eternity is a major contribution to our literature.”

Writers as various as John Dos Passos, John P. Marquand, and Mailer himself praised it vigorously: “I felt then and can still say now that From Here to Eternity has been the best American novel since the war.” Years later, Joan Didion would praise it as well: “It seemed to me that…James Jones had known a great simple truth: the Army was nothing more or less than life itself.” It was number one on the best-seller list for four months and the top-selling novel of 1951. It won the National Book Award. And, of course, it was immediately acquired for the movies.

Who could have foreseen that sixty years later, most people, if they remembered it at all, would know it only from the movie—and the movie from the famous Lancaster–Deborah Kerr roll on the beach? The reputation of From Here to Eternity—and of James Jones himself—wouldn’t last “a couple hundred years after I’m dead”; it would hardly survive its first half-century.

Where would James Jones go when he returned from his five years as an enlisted man in the army? He went home, to Robinson, Illinois, the small town he grew up in and despised.

Advertisement

By the time Jim was born, in 1921, the Joneses were sadly diminished from the days when they were one of the leading families in town. His domineering grandfather still lived in an impressive house, but the money was gone. Ramon Jones, Jim’s sensitive father, was a dentist who would have liked to be a poet, and who would commit suicide while Jim was overseas. Ada Jones, Jim’s mother, had social aspirations and pretensions, and resented their reduced circumstances. She was unkind to her husband and neglectful of her children, particularly hard on Jim. Ada would grow obese, diabetic, and nasty—in her son’s fiction, mothers do not fare well. He remembered her, after her death, as “totally selfish, totally self-centered, and totally whining and full of self-pity.”

He was a small gawky kid with stick-out ears (his father said he looked like “a car coming down the street with both doors open”), and he didn’t fit in. He was belligerent and aggressive, always scrapping; a loner. But though he was a mediocre student, as he grew older he grew increasingly bookish, wolfing down the contents of the local Carnegie Library and already trying to write. He was girl-crazy, sex-crazy, but socially inept and frustrated. (Ada didn’t help: catching him masturbating, she warned him that his hand would turn black, and when he fell asleep, sneaked into his bedroom and rubbed black shoe polish into his palm.)

His social life in Robinson was mostly restricted to the tough guys in town who hung around the poolroom and the bars. When he was just eighteen, desperate to get away, he enlisted in the peacetime military and soon found himself in Hawaii, working as a clerk and radio operator. The work was easy, the life not unpleasant, and he was allowed to take writing courses at the University of Hawaii, where at last he found some encouragement. One day, mowing the grass, he had an epiphany: “I had been a writer all my life without knowing it or having written.” To his brother he wrote, “I laugh at my attempts to write. And yet I cannot change. I must succeed. To be a nonentity would crack my brain and rend my heart asunder. It is all or nothing.”

Everything changed when his outfit was sent to join the battle for Guadalcanal. There he became a fighting man, and under conditions of horror and danger. One day, his biographer, Frank MacShane, relates, he

stepped into the jungle to defecate. Squatting down, with his trousers around his feet, he suddenly heard a high keening sound. Whirling around, he saw a Japanese soldier running at him with a bayoneted rifle. [He] got up as quickly as he could and the two men began a bloody and gruesome duel…. Although the man was badly wounded, he refused to die, and only with the greatest difficulty did Jones finally succeed in killing him. Covered with blood, nauseated, filthy, and exhausted, Jones went through the man’s pockets and found a wallet containing two snapshots of the soldier standing with his wife and child. He staggered back to the command post, told the captain what had happened, and said that he would never fight again.

This incident became a crucial scene in The Thin Red Line.

An ankle injury with complications eventually took him back to the States, first to convalescence in a military hospital from which he went AWOL a couple of times, and then to an honorable discharge, awarded with the complicity of sympathetic doctors—he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. In a letter to his brother he reported that he had told the psychiatrists “that I am a genius (altho they probably won’t believe that); that if they attempt to send me overseas again I’ll commit suicide; that if I don’t get out of the army I’ll either go mad or turn into a criminal.”

On one of his unauthorized trips home to Robinson, he had met one of the two most important women of his life, Lowney Handy, who (seventeen years his senior) took him into her home, her bed, and, eventually, her writers’ colony. She and her husband, Henry, essentially adopted Jim—Henry had no problem with his wife’s adultery, partly due to his guilt at having infected her with gonorrhea, leading to a hysterectomy, a situation Jones appropriated to explain the disastrous marriage between Captain Holmes and his wife, Karen, in Eternity.

Lowney Handy became lover, mother, patroness, nurse, and instructor. She was a vivid personality—a somewhat scandalous presence in Robinson, known for her clamorous opinions and Bohemian behavior. She was disciplined and disciplining: her writers had to follow her rules, not only about their work but about their lives. Wherever he went she (and Henry) would turn up, as when he left town for New York in order to find a publisher, encounter the real (literary) world, and take writing and literature courses at NYU.

He was determined to be edited and published by the famous Maxwell Perkins: Hemingway and Fitzgerald, yes, but more important to Jones, Wolfe. Invading the Scribner’s offices unannounced, Jim succeeded in intriguing Perkins, who declined to publish the callow first novel he had brought with him but was impressed enough to give him a small amount of money against the big army novel in the works. By the time From Here to Eternity was finished, Perkins was dead, but Scribner’s knew what it had, and Jones was launched into the big time with the most successful first novel since Gone With the Wind.

The success of his book astonished, thrilled, and somewhat unsettled him. In New York he became a star, palling around with Mailer and Bill Styron and Budd Schulberg and other writers, but he couldn’t do his work there, and retreated to Robinson to write what he always felt was his masterpiece, the huge (1,266 pages) Some Came Running (1957)—an account of the arrival back home of a bitter, disillusioned thirty-something writer with a minor reputation and a major chip on his shoulder. It took Jones six years to write, and it’s not only his longest book but his most perplexing, almost schizophrenic in the divide between what’s extraordinary about it and what’s terrible.

From the time, nineteen years earlier, when the novel’s protagonist, Dave Hirsh, ran away at the age of seventeen, he hadn’t seen his town drunk of a father, his self-righteously pious mother, and, most important, his older brother, Frank, now a prosperous owner of a jewelry store, on the way up financially and socially, with a shrewd, dominating wife and a pretty young daughter. The conflict between the two brothers is a major concern of the book (in real life, Jones was on happy terms with his older brother), with Frank as the designated target for Jones’s lifelong disdain for the falsities and hypocrisies of middle-class aspirations and conventions. (We’re in Sinclair Lewis territory.) But something unexpected happens as the novel develops: a growing sympathy for Frank’s increasingly joyless existence, expressed through his dissatisfactions with his sexual life—a cold wife, an affair that goes wrong with his elegant, detached bookkeeper, a descent into pathetic voyeurism. Slowly Jones reveals Frank as a tragic figure, perhaps the most fully realized of all his characters; the dark side of Lewis’s Babbitt.

Dave lives in three worlds: his family, his no-good gambling and drinking pals, and the idealized Gwen, a college teacher of English and muse to the young aspirant writers in town, with whom he falls in love. Gwen encourages him, mentors him, even loves him, but won’t sleep with him—although everyone believes she’s an experienced woman of the world, she’s actually a virgin and ashamed to acknowledge it. (This is one of Jones’s nuttiest fantasies.) She’s a sanitized version of Lowney Handy, and her saintly father, an almost-famous poet exuding wisdom and Eastern mysticism, is a stand-in for Henry Handy. Everything about the Gwen sections of the book is fakey, not least her outburst when Dave hands her a long story he’s just finished: “Dave,…it’s magnificent!… This is the best thing youve [sic] ever written. Its one of the best things ever written by anybody of your generation. If not the best.” It’s hard to reconcile such an authorial wet dream with the common sense and cool realism of so much of the rest of Jones’s work.

Dave’s other guru is the town’s leading gambler, ’Bama, an idealized man’s man leaning against the bar downing Scotch and “an adept at the introduction and seduction routines with the bachelor girls.” Women, he explains, “dont [sic] get their pleasure out of sex much, the way men do. Thats all crap these two-bit marriage counciller books put out. A woman gets her pleasure out of givin a man pleasure.” A sad proof of his theory is the wretched, sluttish Ginnie, who will sleep with anyone at all just for the happiness of being taken notice of. But, Dave asks, who had ever treated her like a human being? “Who had ever treated her with the basic dignity that was her right?” It’s Ginnie with whom Dave disastrously takes up and who brings about his futile death.

So much of Some Came Running is ludicrous—not least, Jones’s determination to inflict his ideas about spelling and punctuation on the world: no apostrophes in words like “don’t” and “can’t,” for instance—that when he’s at his best, he seems even better than he is. For me, the most striking stretch of the novel is the twenty-page account of how Dawn—“little Dawnie,” Frank’s daughter, Dave’s niece—decides to marry an appropriate young man. She calculates, she times her campaign, she holds him off until the perfect moment, she fakes virginity, she stars in the perfect wedding, and she makes the marriage work. Jones is usually seen as being unable to write about women, but Dawnie is pitch-perfect, and once again although he sees her—and through her—with absolute clarity, he also sees her with sympathy.

Jones’s success in bringing Dawnie and a number of other secondary characters to life is echoed by his exact representation of Robinson itself, a small town that, due to its oil refineries, was surprisingly affluent. Jones makes us see it, with its courthouse square, its Main Street, its banks and barber shops and barrooms; its country club and American Legion post; its politics and its power plays. Yes, Jones dislikes Robinson (here, called Parkman) and its people and its way of life, but he also has absorbed it and come to realize that he cares for it in spite of himself. “He had never thought he would ever love this miserable, beautiful, backward-in-all-the-wrong-ways, progressive-in-all-the-wrong-ways, petty little Illinois town. But he did.”

The novel’s evocative realism couldn’t protect it from the scathing criticism that greeted its publication. Its length, its longueurs, its odd writing tics, and its combination of self-dramatization and self-delusion triggered a violently negative reaction to which Jones responded with his next book, The Pistol (1959), a compressed army novella—plainly written though with symbolic overtones—whose convincing texture won back the admiration of the critics.

And three years later came The Thin Red Line, his account of the battle for Guadalcanal and his most impressive piece of work. He doesn’t personalize the experience through a single protagonist; instead, he brings to life an entire company of soldiers. They’re wholly individual, yet it’s their collective experience that convinces us that this is the way it was—the way it is. And although the book is at times almost documentary in tone, it is sympathy, not cold objectivity, that allows Jones to get inside these men. In a letter to his editor he described what he was doing: “It’s a very taut, cold-blooded style, not reportorial exactly, but something like that—provided a reporter could comment on the insides of people as well as the outside, if, of course, the reporter was smart enough!”

The governing quality of the book is its honesty: about homosexuality, the ashamed fumblings to relieve tension; about alcohol—the desperate need for it; about cowardice—the big issue. About hatred but also respect for officers. And about the overwhelming awfulness of it all, and the randomness. Why is this one dead, this one alive? There’s an absence of religion and not much patriotism. Instead, there’s battle, there’s unbearable thirst, there’s terror. From Here to Eternity was about the army; The Thin Red Line is about war.

Well before The Thin Red Line was published (to considerable acclaim and success), Jones’s personal life had changed forever. In December 1956, he was introduced by Budd Schulberg to a gorgeous, sexy, intelligent blonde named Gloria Mosolino. Gloria was a sophisticated girl-about-town—“a writer-fucker,” as she called herself, who liked to drink and liked sex. They were married two months after their first date and became a famous and happy couple, and an international one. Moving to Paris, they lived in a grand apartment on the Île Saint-Louis, always on the go, entertaining pals like Bill and Rose Styron and Irwin Shaw. Having a daughter, Kaylie, and adopting a son, Jamie, they steadied down somewhat, and of course Jim was always working.

But what he wrote during these next years makes for a sad story. His worst book, Go to the Widow-Maker (1967), has no redeeming qualities: it’s a self-indulgent chronicle of Jim and Gloria’s relationship, with Jim practically undisguised as a famous playwright. There’s a lot of tedious description of scuba-diving in the Caribbean, with a local diver presiding as the obligatory guru-figure, and a vicious portrait of Lowney: “I know exactly what’s going on, you bastard…. You’ve found yourself some soft luscious pussycunt who is telling you how marvelous you are…. A piece of flufftail who wouldn’t have looked at you before I made you rich and famous.”

The final message is yet again about bravery, about manhood: “Politics, war, football, polo, explorers. Skindiving. Shark-shooting. All to be brave. All to be men. All to grow up to Daddy’s great huge cock they remember but can never match.” Widow-Maker got the reception it deserved, and the book that followed was hardly better—The Merry Month of May (1970), about the 1968 student uprising in Paris, which the Joneses had witnessed close up and which he reported with his usual degree of authenticity, but also proclaiming his addiction to cunnilingus. (“He had been a dedicated pussy-eater since the very first time he had indulged the pastime…. There was something perversely pleasurable in making a woman enjoy sex.”) Then, wearily, an ineffectual stab at a conventional spy thriller, A Touch of Danger (1973), centered on an angry and, at fifty, aging hero.

Finally there was Whistle (1978), long in progress and intended as the final volume of his war trilogy. Jones had asked himself, “How did you come back from counting yourself as dead?” And this is the question Whistle would try to answer. It’s about wounded combat men returning home to a huge military hospital. The men who aren’t too incapacitated drink and whore their days away in nearby Memphis (“Luxor” in the novel), but they’re broken by what they’ve experienced; hopelessly damaged.

Jones, his health rapidly deteriorating, managed to complete all but the final fifteen pages or so of Whistle before his death, and the book was finished by his close friend Willie Morris. It had the most positive reception of any of his works since The Thin Red Line, confirming the idea that military life was his only true subject.

Offsetting the failings of most of his late fiction were two strong works of nonfiction—Viet Journal (1974), the fruit of a five-week sojourn in Vietnam in 1973 at the behest of The New York Times, and a year later, WWII, a remarkable history intended as text to accompany a collection of war art. This was a substantial effort—he had both the long view and the personal one, having not only experienced the war but having thought long and hard about it. His conclusions were somber:

Everything the civilian soldier learned and was taught from the moment of his induction was one more delicate stop along this path of the soldier evolving toward acceptance of his death. The idea that his death, under certain circumstances, is correct and right. The training, the discipline, the daily humiliations, the privileges of “brutish” sergeants, the living en masse like schools of fish, are all directed toward breaking down the sense of the sanctity of the physical person, and toward hardening the awareness that a soldier is the chattel (hopefully a proud chattel, but a chattel all the same) of the society he serves and was born a member of. And is therefore as dispensable as the ships and guns and tanks and ammo he himself serves and dispenses.

By 1974, the Joneses were not only under serious financial pressure but after seventeen freewheeling years in Paris, Jim was chafing at the ways of the French and frustrated by his feeble grip of their language. That summer the family sailed for home, first to Florida where he taught for a year, then for the north, where in 1975 they settled in the Long Island beach town of Bridgehampton. Once again Gloria created a rich social life for the family, the house a magnet for the many writers who lived in the neighborhood or came visiting—the Irwin Shaws, the Styrons, Peter Matthiessen, Truman Capote, Joseph Heller, Kurt Vonnegut, Willie Morris, et al. As always, Jim was well liked, even loved. But his heart was giving out—he had lived for decades with the knowledge that he was likely to die young. On May 9, 1977, his heart stopped. He was only fifty-five years old.

Gloria stayed on in the Hamptons, mythologized and self-mythologizing. Willie Morris saw her “as one of the truly great women of America.” In her daughter Kaylie Jones’s lacerating memoir, Lies My Mother Never Told Me, she is a destructive and self-destructive alcoholic. Jim had been a good father, but clearly he and the acutely narcissistic Gloria were more interested in each other than in their children.

His reputation has survived less well than his children have, however. It rests on the war novels, and who reads them? James Jones is a dead white male, and his strong suit was direct narration and honest dialogue. Writers like Heller and Vonnegut and Pynchon and DeLillo put him out of business. He wasn’t a modernist or a postmodernist or a magic realist—he was just a plain old realist. And when he strayed from war, he was usually pretentious or empty. What’s more, his books were very long and very raw; they couldn’t be assigned to kids. And what college courses were going to adopt him?

Recently, however, almost all his work has been reissued, and an ambitious digital-publishing company has made everything available on e-books, adventurously restoring to From Here to Eternity the words and passages that in 1951 Jones had reluctantly agreed to suppress. Perhaps this new availability will help establish him as America’s strongest chronicler of war, and also help us begin to recognize him as a writer of deep sympathies and a large humanity. In a letter to Burroughs Mitchell, he said, “I do not want to become a Dreiser, or [Frank] Norris or [James T.] Farrell—despite reviewers. I want to love people—including myself.”