In 1947, Stefan Jędrychowski, a Communist veteran, member of the Polish Politburo, and minister in the government, wrote a memo to his colleagues on a subject close to his heart. Somewhat pompously entitled “Notes on Anglo-Saxon Propaganda,” the memo complained, among other things, that British and American news services were more influential in Poland than their Soviet and Polish equivalents, that American films were too warmly reviewed, and that American fashions were too readily available.

But above all, Jędrychowski was annoyed by the clout of Polska YMCA, the Polish section of the Young Men’s Christian Association, an organization founded in Warsaw in 1923 and then banned under the German occupation. In April 1945 Polska YMCA had restarted itself with some help from the international YMCA headquarters in Geneva and a good deal of local enthusiasm.

The YMCA was avowedly apolitical. Its main tasks in Poland were the distribution of foreign aid—clothes, books, food—and the provision of activities and classes for young people. Jędrychowski suspected ulterior motives, however. The YMCA propaganda, he wrote, was conducted “carefully…avoiding direct political accents,” which of course made it more dangerous. He recommended that Comrade Radkiewicz, the minister for state security, conduct a financial audit of the organization and monitor carefully which publications were being made available and what kinds of courses were being taught.

He was not the only one who was worried. At about the same time, the Education Ministry also received a report from leaders of the Communist youth movement, then known as the Union of Fighting Youth (Związek Walki Młodych, or ZWM), who loathed the YMCA even more than Jędrychowski did. The young Communists were irritated by the YMCA’s English classes, clubs, and billiards games. In Gdańsk, they complained, the organization sponsored dormitories and dining halls, and gave away used clothes. In Kraków it had rented a building with a seventy-five-year lease. Though they didn’t say so, all of this was far more than they themselves were capable of doing.

There may have been darker concerns: in the period just after the Bolshevik revolution, a British agent named Paul Dukes had actually used the YMCA in Moscow as a cover for his espionage activities, though not with any particular success. But the Polish Communists wouldn’t have needed to know that piece of history in order to find the Warsaw YMCA irritating. They hated the YMCA because it was fashionable, if there could be said to be such a thing as fashion in postwar Warsaw. The Warsaw YMCA was, for example, the abode of Leopold Tyrmand, a novelist, journalist, and flaneur, as well as Poland’s first and greatest jazz critic. Tyrmand rented a room in the half- destroyed building after the war that was, as he later wrote, “two and a half metres by three and half metres—in other words a hole. But cozy.” All around was nothing but mud, dust, and the ruins of Warsaw: this gave the building, a mere dormitory for single men, the air of “a luxurious hotel.” It wasn’t much, but it was clean and quiet.

In the evenings, Tyrmand dressed in brightly colored socks and narrow trousers, the latter specially made for him by a tailor who also lived at the YMCA, and went to the jazz concerts downstairs. There, “between the cafeteria, the reading room and the swimming pool the best girls ambled about in the then-fashionable style of swing.” Both the Warsaw and Łodz YMCA branches were renowned for these concerts. One fan remembered that getting a ticket to a YMCA concert was “a dream…it was cultured, elegant, hugely fun, even without alcohol.” More than anything else it was entertainment: “We didn’t know anything about Katyń or about how one lives in a free country, we didn’t have passports, we didn’t have new books or movies, but we had a natural need to find entertainment, fun…that was what jazz gave us.” Tyrmand himself wrote later that the YMCA represented “genuine civilization in the middle of devastated, troglodyte Warsaw, a city where one lived in ratholes. Above all we valued the collegial atmosphere, the sportiness, the good humour.”

But with enemies like Jędrychowski and the Union of Fighting Youth, the organization could not last. Under pressure since 1946, by 1949 the Communist authorities had declared the YMCA a “tool of bourgeois-fascism” and dissolved it. With bizarre, Orwellian fury, Communist youth activists descended on the club with hammers and smashed all the jazz records. The building was given over to something called the League of Soldiers’ Friends. The inhabitants were harassed, first with early-morning noise, later with cuts in water and electricity, in order to get them to move out. Eventually, the young Communists threw everyone’s possessions out of the windows of the building and removed their beds.

Advertisement

According to the standard version of postwar Eastern European history, the attack on the YMCA, which began in 1946–1947, should not have happened. For until recently, most historians of this era divided the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe into phases. First there was a moment of “genuine democracy” in 1944–1945 following the defeat of Germany and liberation; then, briefly, a period of “bogus democracy,” as Hugh Seton-Watson once described it, in which different political tendencies emerged into the open and it seemed as if some opposition groups might have a chance of surviving. Then, in 1947–1948, there was an abrupt policy shift and a full-fledged takeover by Communists: political terror was increased, the media muzzled, elections manipulated. All pretense of national autonomy was abandoned.

Some historians and political scientists have since blamed this change in political atmosphere on the onset of the cold war, with which it coincided. Sometimes, this imposition of Stalinism in Eastern Europe is even blamed on Western cold warriors, whose aggressive rhetoric allegedly “forced” the Soviet leader to tighten his grip on the region. In 1959, this general “revisionist” argument was given its classic form by William Appleman Williams, who argued that the cold war had been caused not by Communist expansion but by the American drive for open international markets. More recently, a prominent German scholar has argued that the division of Germany was caused not by the Soviet pursuit of totalitarian policies in eastern Germany after 1945, but by the Western powers’ failure to take advantage of Stalin’s peaceful overtures.

But any close examination of what was happening on the ground across Eastern Europe between 1944 and 1947 reveals the deep flaws of these arguments—and, thanks to the availability of Soviet as well as Eastern European archives, a close examination is now possible. New sources have helped historians understand that the early “liberal” period was, in reality, not quite so liberal as it sometimes appeared in retrospect, or to outsiders. Not every element of the Soviet political system was imported into the region as soon as the Red Army crossed the borders.

Indeed there is no evidence that Stalin expected to create a Communist “bloc” very quickly, although in Poland he set up the compliant “provisional” government in Lublin right away. In 1944, Stalin’s deputy foreign minister, Ivan Maisky, wrote a note predicting that the nations of Europe would eventually all become Communist states, but only after three or perhaps four decades. (He also predicted that in the Europe of the future there should be only one land power, the USSR, and one sea power, Great Britain.) In the meantime, Maisky thought the Soviet Union should not try to foment “proletarian revolutions” in Eastern Europe and should try to maintain good relations with the Western democracies.

Yet the Soviet Union did import certain key elements of the Soviet system into every nation occupied by the Red Army, from the very beginning. First and foremost, the Soviet NKVD, in collaboration with local Communist parties, immediately created a secret police force in its own image, often using people whom it had already trained in Moscow. Everywhere the Red Army went—even in Czechoslovakia, from which Soviet troops eventually withdrew—these newly minted secret policemen immediately began to use selective violence, carefully targeting their political enemies according to previously composed lists and criteria.

Secondly, in every occupied nation, the Soviet authorities, while briefly allowing non-Communist newspapers and magazines to appear, placed trusted local Communists in charge of the era’s most powerful form of mass media: the radio. In the long term, the authorities hoped that the radio, together with other propaganda and changes to the educational system, would help bring the masses into the Communist camp.

Thirdly, wherever it was possible, Soviet authorities, again in conjunction with local Communist parties, carried out policies of mass ethnic cleansing, displacing millions of Germans, Poles, Ukrainians, Hungarians, and others from towns and villages where they had lived for centuries. Trucks and trains moved people and a few scant possessions into refugee camps and new homes hundreds of miles away from where they had been born. Disoriented and displaced, the refugees were easier to manipulate and control than they might have been otherwise. To some degree, the United States and Britain were complicit in this policy—ethnic cleansing of the Germans would be written into the Potsdam Agreement—but few in the West understood at the time how extensive and violent Soviet ethnic cleansing would turn out to be.

Finally, Soviet and local Communists harassed, persecuted, and eventually banned many of the independent organizations of what we would now call civil society, from women’s groups and athletic associations to church organizations and private kindergartens. In particular, they were fixated, from the very first days of the occupation, on youth groups: young social democrats, young Catholic or Protestant organizations, boy scouts and girl scouts. Even before they banned independent political parties for adults, and even before they outlawed church organizations and independent trade unions, they put young people’s organizations under the strictest possible observations and restraint.

Advertisement

In fact, the attacks on youth groups in many of the nations occupied by the Red Army began well before other policies had been set into motion. Polska YMCA was only one of many youth groups to reemerge from the rubble of the war. In an era before television and social media, and at a time when many lacked radio, newspapers, books, music, and theater, youth groups had an importance to teenagers and young adults that today is hard to imagine. They organized parties, concerts, camps, clubs, sports, and discussion groups of a kind that could be found nowhere else.

In Germany, the disappearance of the Hitler Youth and its female branch, the League of German Girls, left a real gap. Until the very end of the war, nearly half of the young people in Germany had attended Hitler Youth and League of German Girls meetings in the evenings. Most had spent their summers and weekends at organized camps as well. As soon as the fighting stopped, former members and former opponents of the Nazi youth groups began spontaneously to form antifascist organizations in towns and cities across both East and West Germany.

These first groups were German, not Soviet, and they were organized by the young people themselves. All around them, adults were in despair. One in five German schoolchildren had lost his or her father. One in ten had a father who was a prisoner of war. Someone had to start reorganizing society, and in the absence of adult authorities a few very energetic young people took on this task. In Neukölln, a western Berlin district, an antifascist youth organization created on May 8, 1945—the day before the armistice—had six hundred members by May 20, and had already set up five orphanages and cleared two sports stadiums of rubble. On May 23, the group gave a performance in a Neukölln theater that was attended by Soviet military officers as well as the general public.

The young Communist Wolfgang Leonhard, who had by then arrived in Berlin from Moscow on the plane of the German Communist leader Walter Ulbricht, met some of the members of this Neukölln group. These were the first non-Soviet political activists he had ever encountered:

One could feel the genuineness of the enthusiasm combined with a healthy realism. Without waiting for directives, the [group’s] members had immediately realized that the first thing was to organize a supply of food and water to alleviate the most urgent needs of the population.

Leonhard marveled, among other things, at their efficient, businesslike discussions: “More was accomplished in half an hour than in all the endless meetings I was used to in Russia.” Similar groups began organizing food distribution and rubble clearance all across Berlin, which was entirely under Soviet control for the first couple of months after the armistice. The Western allies arrived in July, and only then was the city divided into occupation zones. By that time, the Berlin magistrate reckoned that ten thousand teenagers across the city had already joined spontaneous antifascist groups.

But almost as soon as they had started, these groups attracted the attention and suspicion of the Soviet authorities in Germany. On July 31, the Soviet Military Administration issued a declaration “permitting” the formation of antifascist groups under the leadership of city mayors, but only “in connection with formal requests.” Unless they received explicit permission, in other words, all other youth organizations, unions, and sports clubs—even socialist groups—were banned. Separately, another declaration also commanded all youth groups to promote “friendship” with the Soviet Union. After three months of spontaneous existence, these self-organized groups were already coming under state control.

Leonhard, who had just encountered spontaneous civil society for the first time in his life, was now given the task of destroying it. When the CP’s own youth section failed to gain a following, the future East German leader Erich Honecker, then charged with corralling the youth groups, began surreptitiously organizing a “spontaneous” popular movement to unify German youth. The push for the unification of all German youth groups under a single umbrella was to originate in Saxony, and would involve petitions, meetings, and speeches. Prominent youth leaders would be encouraged to send letters to the Soviet authorities calling for a single, nonpartisan youth group.

Once the Soviet military leaders agreed to this plan, then the “bourgeois” youth leaders would have no choice but to go along: all of the young people would belong to the new group, and the relative weakness of the young Communists would not be so noticeable. When Ulbricht returned from Moscow with official permission to put the youth group under Communist control, the Free German Youth (Freie Deutsche Jugend, or FDJ) was born.

The “spontaneous” call for unity took the other youth leaders by surprise. At a meeting called to discuss the matter, Honecker claimed that “many” groups were demanding a unified, Free German youth movement, and when Christian Democratic and Social Democratic youth leaders said they had not heard any such demands, they were shown several baskets containing hundreds of letters. “The surprise was a success,” remembered one prominent young Christian Democrat, Manfred Klein. “We had not reckoned with such a suggestion at that time.” A founding congress was duly organized and a range of young people—Christian Democrat, Social Democrat, Communist—agreed to attend. So did Catholic and Lutheran youth leaders, albeit cautiously. Klein discussed the meeting with Jakob Kaiser, then the leader of the Christian Democrats in Berlin, who agreed that he would take part but advised Klein to be wary: “None of us knows how long this will work.”

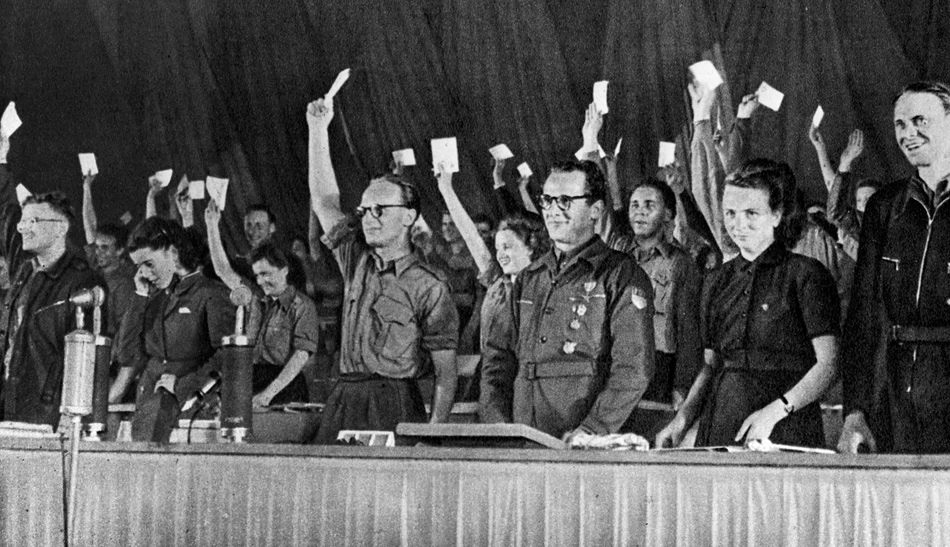

The first meeting was held in Brandenburg in April 1946 and it started out optimistically. It began with a song (“The Ballad of Free Youth”) and the unanimous selection of a presidium that included Klein and Honecker. There were several speeches of welcome. Colonel Sergei Tulpanov, the cultural commissar of the Soviet occupation forces, told the young people that “Hitler’s ideology has left deep traces in the consciousness of German youth” and complimented those in the room, somewhat patronizingly, on having grown out of it. “We know how hard you have worked in order to purge yourselves of all of that.” Welcome speeches were followed by more speeches: on the achievements of youth, on the importance of the inclusion of girls, on the need for nationalized industry, on the perfidy of the West. Many of the speakers addressed the hall as “comrades.” One or two Catholic representatives got up to speak. Yes, we want to unite, said one, “unite in the love of Germany.”

But although the mood in the hall itself was reconciliatory, the mood in the corridors was less so, and by day three the atmosphere had turned sour. That morning, some of the more radical Communist delegates held a meeting in a side room, during which one of them had complained about the church group leaders. He thought they should be expelled. The Communist officials told him not to worry, the religious young people would be kept under control: “We will give the churches ten blows a day until they lie on the ground. When we need them again, we will stroke them a little until their wounds are healed.”

Unfortunately, one of the Catholic youth leaders overheard these words, took notes on the dialogue, and reported back to his colleagues. Klein and several Catholic leaders announced that they would refuse to join the new organization. Some shouting back and forth followed, and a Soviet officer, Major Beylin, intervened. He promised the Catholics that they could have some autonomy within the organization, whereupon they agreed to stay. The Soviet occupiers were, in 1946, still anxious for their occupation zone at least to appear democratic and multifaceted.

That desire did not last. In the end, the congress elected sixty-two members to the new organization’s central council, of which more than fifty were either Communists or Socialists. Separately, the Communists allotted to themselves all the important jobs. Honecker, a Communist of blind dedication, became and would remain the Free German Youth’s leader until long after he had ceased to be a youth himself (he resigned from the Free German Youth in 1955, when he was forty-three years old). A Free German Youth training school was quickly opened in Bogensee. Here, Klein remembered, “the real intentions of Honecker and his comrades became apparent very quickly…. The boys and girls were trained in Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist ideology and got precise directives on what they had to do to help socialism win in the enterprises and the country.”

Other groups were simply dispersed. In the spring of 1946, Soviet authorities discovered that an unregistered evangelical youth group, Christian Endeavor (Entschieden für Christus), was active in Saxony, where it held Bible discussions and prayer meetings. “This proved that control on the activity of German organizations is weak,” the Saxon authorities declared, and they immediately banned the organization. Another group that set up an “independent” cell of the Free German Youth in Leipzig met a similar fate. Although the leaders of the group argued that their members were more intellectually inclined than the “workers” in the mainstream Free German Youth, and that they therefore needed their own organization, they were abruptly disbanded too. One Soviet report complained that many of the groups that had religious affiliations “act far outside the frame of religion” and were engaging in “cultural-political work with youth,” which is of course what church youth groups had always done.

In the winter of 1946, the Soviet authorities at Karlshorst also informed the brand-new German cultural administration—part of the German bureaucracy set up to enact Soviet policy—that artistic and cultural groups of all kinds, whether for children, young people, or adults, were illegal unless they were affiliated to “mass organizations” such as the Free German Youth, the official trade union organization, or the official cultural union, the Kulturbund: “otherwise they cannot be controlled.”

A German inspector sent out by the Communists to assess the situation of “associations” at this time seemed particularly horrified by the large numbers of independent chess clubs. She called upon Soviet and German cultural authorities to eliminate these groups—not only chess clubs, but sporting clubs and singing clubs—a task that was not finished until 1948–1949. Other apolitical organizations were banned right away. Hiking clubs were strictly forbidden, for example, presumably because the Hitler Youth had a particular fondness for hiking (though the Wandervogel, the famous German hiking and nature clubs founded at the end of the nineteenth century, had once had left-wing as well as proto-Nazi sympathies).

Klein kept working within the system. Though frustrated with his role as the “token Christian” inside the Free German Youth, he spent a good bit of his time trying to organize the other token Christians into a voting bloc. He lobbied to keep the Free German Youth open to many different kinds of young people, but to no avail. Almost exactly a year after its founding, the brief Soviet–German experiment in nonpartisan youth politics had come to an end. On March 13, 1947, the NKVD arrested Klein, along with fifteen other young Christian Democratic leaders. A Soviet military tribunal sentenced him to a Soviet labor camp. He remained there for nine years, returning in 1956. He spent the rest of his life in West Berlin.

By the early 1950s, Eastern Europe’s secret policemen were ready to finish the task they had begun in 1945: the elimination of all remaining independent social or civic institutions, along with the exclusion from public life of anyone who might still sympathize with them.

This Issue

November 22, 2012

The Politics of Fear

The Winner: Dysfunction

Election by Connection