With his great theme of Americans and their avid encounters with European experience, Henry James might have found the Quay brothers to be updated versions of some of his own characters. Something like a romance with European life and culture, anyway, seems to be at the center of the art of Timothy and Stephen Quay. They are identical twins who were born in 1947, outside Philadelphia, and have lived and worked side by side in London for decades. They are best known for their stop-motion animated films, made with puppets, and to take in these films is to become immersed in a kind of Expressionist fairy tale. More precisely, one feels that, in some of their most engaging and affecting movies, they speak to us from a deep imaginative rapport with the spirit, and tensions, of Central Europe and of German-speaking Europe in the years before and after World War I.

Not that the Quays, who have been fairly well known in Europe for some time but have had primarily an underground reputation here—and are currently the subject of an overdue retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—set out to make historically accurate costume dramas. Nor, in their large and dizzyingly diverse body of work, do they limit themselves to one particular time and milieu. Over the past thirty years, they have used their puppet art in making short films based on their own highly particular concerns (such as the Czech artist and animator Jan Švankmajer) and on fiction by (or on aspects of the lives of) Kafka, the Polish writer Bruno Schulz, and the Swiss writer Robert Walser. The brothers have also made short and feature-length movies with actors—including In Absentia, a demanding and wrenching work about a woman who was confined to a Heidelberg mental hospital in the early twentieth century.

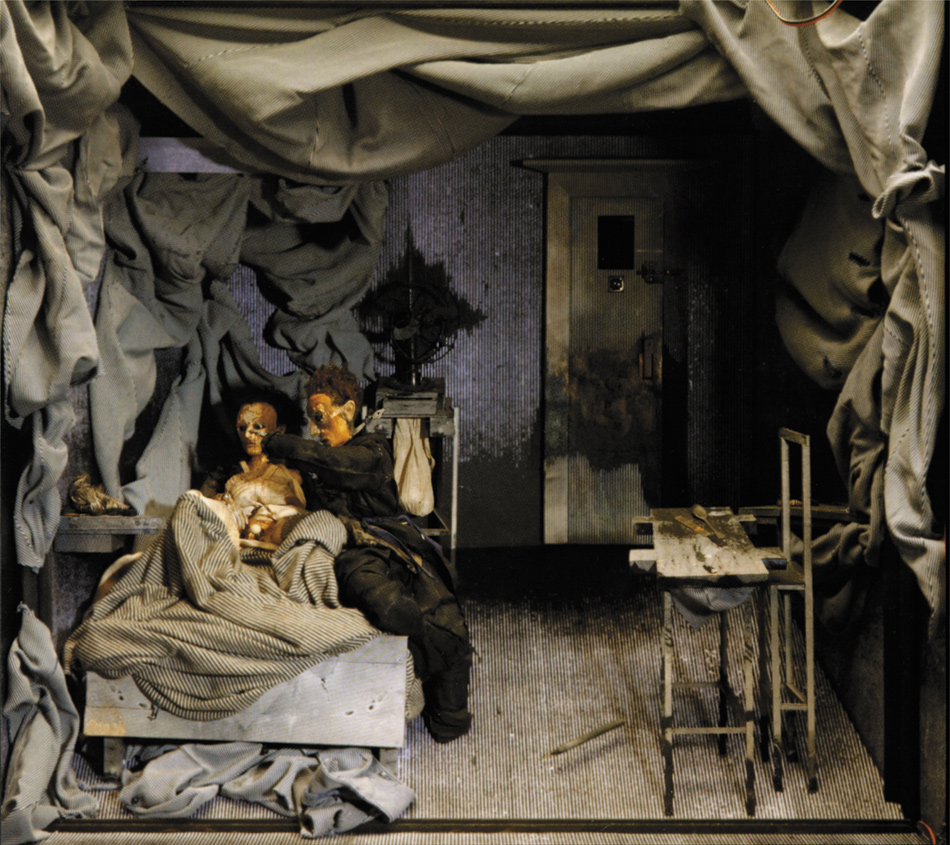

Then, too, the Quays have employed roughly the same kind of animation that they use for Kafka or Schulz for music videos (funded by MTV) and for TV commercials (for Nikon, Doritos, Honeywell, Badoit, and others), which have run on British TV. They have used their stop-motion art for documentaries (often commissioned by the BBC) on such subjects as Stravinsky, Bartók, Janáček, and Michel De Ghelderode, a Belgian who wrote plays for puppets. Primarily for English companies, they have done stage sets for theater, opera, and ballet productions. At the Modern’s show, in addition to seeing many of the Quays’ movies (and footage of events they have worked on), one encounters many of the sets they have created for these movies. They are minia ture dioramas, packed with amazingly intricate details, and are clearly meant to be taken as self-contained artworks in themselves. We can also see some of the puppets that have been moved about on these sets.

Amorphous as the Quay universe may sound in such an account, there is an underlying tenor to their art. It is, one might say, the meeting place of the macabre, the tormented, and the fantastic. Especially in the movies they have made for themselves, and to a lesser degree in their MTV shorts, which together represent for me the Quays’ most inventive work, we are taken into a dreamlike and disorienting, and sometimes merely weird and confounding, realm. It is, broadly speaking, the dark and possibly treacherous forest of folk tales, which is what the Modern’s exhibition looks like. With its dark gray walls, angled pathways, separate, small zones to look at films, and a grove of birch trees, which shelters a blown-up photo of the twins as children—they are watching their mother, whose close physical resemblance to her sons is startling—the exhibition turns its viewers into so many Hansels and Gretels.

On the face of it, the material the Quays are drawn to, which recalls, among other things, the Surrealist art of Max Ernst and the films of David Lynch and Tim Burton, is deflatingly familiar. The brothers studied to be illustrators, and for most of the 1970s they attempted to make a living by designing book jackets or album covers, or supplying illustrations for magazines. They also created highly finished drawings for themselves. A lot of this work (along with a selection of Polish posters from the 1960s, which initially inspired them) is on view at the show, and little of it is beckoning. In pictures that feel fairly stale and generic, we see deformed and violently damaged bodies, winged nightmare creatures, and disembodied hands. Mystery trams move through Gothic cities with empty streets, and in a drawing called “Kafka’s The Dream,” a figure walks by with a sword plunged into his back.

The great insight of the Quays was their seeing that this material could have a subtler and more complex life in the form of a filmed puppet theater. They had made movies as students, in their early twenties, and by some point in the mid-1980s they found a fresh way to present their taste for freakish or psychologically strained situations. Especially in their music videos and their commercials, moviemaking released as well their talent for rather steamy situations and for witty and happily absurd ones (as in a 1996 ad for Murphy’s Irish Stout that builds on Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai). Their roughly twenty-minute-long Street of Crocodiles (1986), based on material by Bruno Schulz, has been called their breakthrough work, and it is rightly acclaimed. This color movie represents a rare example of contemporary artists being able to honor, and yet make personal to themselves, an aspect of a literary classic.

Advertisement

Schulz’s story, which can be found in his 1934 collection of stories The Street of Crocodiles, presents, in more of an essay than a narrative, a tour of a commercial and industrial zone in the city the young narrator lives in. It is a place where everything is ersatz, or “suspect and equivocal,” as Schulz writes, and even the pervasive note of licentiousness turns out to be a sham. In the Quays’ version, the lurking disquiet is in no sense diminished, but it is seen in a more concrete and surprising way.

Our hero is a wary puppet figure with a harshly angular face and a crouching, Groucho-like walk. He enters the dust-filled, blearily illuminated “street of crocodiles” where he sees mysterious, creakily moving power lines, which periodically, on their own accord, get knotted up and then untangled. Screws also have a life of their own. They unscrew themselves from wherever they have been living, so to speak, and then, after taking a roll in the sensuous, thick dust, they scurry off and screw down elsewhere. Best of all are the tailors’ dummies the protagonist encounters in a fabric shop. They turn out to be fast-moving marauders who remove our hero’s head and swiftly and viciously turn him into another dummy.

The Quays are not easy to get a handle on, at least as moviemakers. In this art form, they are hands-on technicians and expert craftsmen and, too, formal, abstract artists. They are also erudite enthusiasts who like to bring their discoveries into their films in some way. And they are creators with distinct literary concerns.

They have never, in addition, lost their feeling for graphic design, and have incorporated their interest in calligraphy, optical illusions, and typefaces into their art. In some of their movies the lines in bar codes, or spoons with suddenly elongated shafts, take over the scenes, like supporting actors having their moments. The credits in their films, which they have clearly designed (and which always flash by too quickly)—they generally have an intricately rubbery, or cursive, or spiky look—are little components in the overall experience of the films.

The Quays’ stop-motion animation has a flow and sense of movement that sets it apart from most such work. A Quay movie tends to be a kind of stew of coming-into-focus and going-out-of-focus images, and of jumpy and flickering moments—mixed in with (sometimes excessively) drawn out and repetitive ones. There is generally no dialogue, though voices, often muffled and sometimes in German, can be heard. Even in their almost consistently suspenseful Street of Crocodiles, you can thus find yourself drifting off, and then realize that some images have come and gone so quickly that you have barely registered them.

Underlying the particular rhythm of a Quay movie, where frazzled sequences alternate with stately and circling ones, must be the fact that the brothers begin filming only after they have in hand the prospective picture’s musical score (many of which have been written by the Polish composer Leszek Jankowski). Their movies, as they put it in a self-interview that appears in the catalog of the show, “obey musical laws and not dramaturgical ones.” In a sense, the brothers remain illustrators—but of music.

Movement in itself provides some of the genuinely magical moments in their films (making it not a complete surprise that the Quays, who are tall and described in the catalog as “agile,” at one point contemplated careers in sports). The charming and sexy Stille Nacht II: Are We Still Married?, a 1992 black-and-white music video about a curious and chivalrous stuffed rabbit and a woman mannequin he seeks to protect, set to a haunting song by the group His Name Is Alive, is made up of one small choreographed move after another—beginning with the seemingly aloof woman gently rising on her toes, as a sign that she could be interested, followed by the still-mystified rabbit trying out the same lift himself.

Advertisement

Bodily gestures, and the sheer flow of one scene into another, may be the high points of the Quays’ Institute Benjamenta, or This Dream People Call Human Life (1995), their first feature film. Based on Robert Walser’s 1909 novel Jakob von Gunten, which takes place at a school for butlers, the elegantly shot black-and-white movie includes Mark Rylance as Jakob and Alice Krige as Fräulein Benjamenta.

As is noted in the writing about the Quays, Walser, with Kafka and Schulz, forms a kind of cornerstone of the brothers’ thinking. The three somewhat contemporaneous writers strike distinctly separate notes, of course. Where Kafka and Schulz, in quite different ways, present situations that can become fantastical and lead to mythically large ramifications, Walser speaks, with a novel and sometimes provocative innocent directness, of whatever he encounters as an invariably lone observer. But all three writers take off from everyday, seemingly inconsequential, even lowly material. With their little puppet actors and tabletop stages, coupled with the magic-trick nature of stop-motion animation, where screws, thread, or the broken-off points of pencils can become active parts of a story, the Quays very literally work with lowly material.

They have, moreover, made clear their allegiance to different forms of what they call, in a statement in the Modern’s catalog, “the marginal.” They have pointed out, for example, that it is Kafka’s diaries and notebooks that they find meaningful, not his novels. In the same catalog statement, they note how crucial the “Treatise on Tailors’ Dummies” section of The Street of Crocodiles is for them. It is here that Schulz writes about the buried life in inanimate things—not only tailors’ dummies but furniture or wallpaper—and thinks of “matter” as being, as the Quays put it, “in a constant state of migration.” Walser’s lifelong belief, in turn, in the importance of small gestures and momentary perceptions, and his distrust of anything assured of its own importance, might be called a less mystical complement to Schulz’s thought.

The Quays may have been attracted to Jakob von Gunten because Jakob, who narrates, personifies Walser’s rejection of the grand. Jakob’s ever-changing voice is what this rich and intense short novel is about. He is as impudent, and at sea about what to make of himself (and of his infatuation with his fellow student Kraus), as he is confident that, as he says, thinking of his future, “Me, I shall be something very lowly and small.” An occasional realist as well, he is capable of recognizing about himself that his “modesty knows no limits, as long as one flatters his spirit.”

This many-layered Jakob is missing from the film. As Mark Rylance has been directed, he seems more cautious than cheeky, let alone psychologically astute. But in its feeling for light and its scenes where Jakob and his classmates go about their lessons, and, as they do so, move into swaying dance sequences (which is in the novel but not elaborated), the movie makes us forget about comparisons with Walser entirely.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the Quays becoming filmmakers is how, in the process, they transformed the physical and psychological violence that marked their youthful work on paper. It didn’t disappear, but it became veiled, and we feel it more. A fully believable atmosphere of crisis and hopelessness pervades In Absentia (2000), which obliquely presents the madness of Emma Hauck, a German woman who spent the last eleven years of her life in a psychiatric clinic, dying there in 1920, in her early forties. Her chief activity was writing to her husband (in letters that, we see in a shocking moment, were never sent).

Hauck’s story, as the Quays note in their catalog interview, is “heartbreaking.” On sheets of paper that became, by the end of a given day, a nightmarishly unreadable jumble of markings (and have been preserved), she wrote only the words “Come, Sweetheart Come.” Set to a fiery and insistent score by Karlheinz Stockhausen, the roughly twenty-minute film has no dialogue, and intersperses scenes of Hauck at a writing table, her fingers encrusted with graphite, with images of, among others, a desolate, fogbound landscape, a doll’s legs swinging, and wind ruffling the curtains of a mansion in a dusky light. The movie is grueling and presents an experience that is not easily shaken off. It leaves us feeling that we have been taken almost physically into a psychotic state where purposefulness and purposelessness are one and the same.

An even more inventive look at psychic imprisonment, and possibly the strangest film the Quays have made, is Stille Nacht I: Dramolet (1988). As a title informs us, it is “Für R.W. in Herisau”—or for Robert Walser in the mental institution near Herisau, in Switzerland, where he was taken in 1933, when he was fifty-five, and lived until his death, in 1956.

Piteous, scary, and funny, the movie shows a doll character who, from his rustic retreat, watches as mysterious filaments sprout everywhere, like little tufts of grass, and twitch and wave about, even in the bowl he expects to eat from. All matter is alive. A squadron of spoons juts out from the wall behind him, and suddenly we wonder if he is imagining it all. At about two minutes in length, the film is over before it begins, and this is part of its power. Walser, Kafka, and Schulz might all, one feels, have been impressed.

This Issue

November 22, 2012

The Politics of Fear

The Winner: Dysfunction

Election by Connection