In an upstate New York diner, a teenager high on “reefer” tries to shoot a pen from his friend’s hand, and ends up putting a hole in a coffee urn, sending a stream of hot coffee sailing toward the window. In the library of a decaying old mansion, a middle-aged man shakes open his father’s books and watches dollar bills rain to the ground. At a Canadian carnival, a boy and a mangy old bear cling together on a roller coaster, soaring and dipping. And in a remote African village, a massive, heartsick, inarticulate American prays for rain in a language he doesn’t understand—and the rain comes.

With a novel as full of surreal tableaux as Henderson the Rain King, that careens from continent to continent and from the ridiculous to the sublime, perhaps the best place to start is with a small oddity: Obersteiner’s allochiria. “I fought it until I came across the term Oberstein’s allochiria, and there I broke down,” says Eugene Henderson, the novel’s shambling pilgrim hero, as he tries to make his way through the recondite medical texts handed him by Dahfu, the King of the Wariri. “I thought, ‘Hell! What is it all about!’” The term sounds fantastic enough to be another of Saul Bellow’s inventions; but there really was a nineteenth-century Austrian neurologist named Heinrich Obersteiner, who diagnosed a rare syndrome in which the brain transposes sensations from the left and right sides of the body to the opposite sides.

The phenomenon appeals to Dahfu, and to the novelist who created him, because of the way it seems to upend the standard relation between mind and body. As good scientific rationalists, we have learned that the mind is the product of the body; where earlier generations spoke of the soul or spirit, we speak only of epiphenomena of the brain. In allochiria, however, we can glimpse for a moment the complementary truth that the body—the way we perceive and live in the body—is also a product of the mind. And if the mind is powerful enough to turn left to right and right to left, could it also be able to shape the body’s growth and form? Could the body be not just the vessel of the self, but the self’s faithful portrait? Dahfu is certain: “There are cheeks or whole faces of hope, feet of respect, hands of justice, brows of serenity, and so forth…The spirit of the person in a sense is the author of his body.”

“Why, King…that’s the worst news I ever heard,” responds Henderson. As well he might. For Bellow does not let us forget for a moment how bizarre he looks, how he combines strength and size with grotesque ferocity: “I was huge but helpless, formidable in looks, but of one piece like a totem pole, or a kind of human Galápagos turtle.” When Henderson and his guide and translator Romilayu first enter the village of the Arnewi, they are greeted by a young girl who bursts into tears. Henderson can hardly blame her for this reaction:

“Shall I run back into the desert,” I thought, “and stay there until the devil has passed out of me and I am fit to meet human kind again without driving it to despair at the first look?”

Indeed, it is his terrible effect on everyone he knows that has driven Henderson out of America in the first place. The first four chapters of the novel, before he arrives in Africa, are like the overture to a comic opera, as Bellow conjures his protagonist by recounting his misadventures. Here is Henderson trying to gun down a housecat, and threatening suicide, and wagging his head and saying “Tchu-tchu-tchu!” and finally ranting so terribly that he induces a fatal attack of some kind in his timid housekeeper. It is all so vividly antic that the reader must wonder what kind of novel he has stumbled into: too whirling and smiling to be a philosophical novel, surely, yet too sad and harsh for comedy.

The only thing to do is to go along with Bellow, for whom the creation of character is never a matter of painting a verbal portrait or recounting a life history. What brings a Bellow hero to life is precisely his turbulence, the “disorderly rush” of thought and feeling that we begin to hear on the first page and stay with until the very last. The harsh syncopation of Eugene Henderson’s inner life corresponds to—or, if Dahfu is right, creates—the powerful ugliness of his face and figure.

In this sense, Henderson the Rain King can be thought of as something in between a novel and a poem. What is at stake is not so much the narration of events as the evocation of a way of being—as Henderson puts it, “listening to the growling of my mind.” The same is true of the other great novels of Bellow’s middle period, which began with Henderson in 1959 and continued through Herzog in 1964 and Humboldt’s Gift in 1975. (“Three H’s,” he wrote to his friend the novelist Richard Stern, “as if I’m finally getting my breath.”) Moses Herzog and Charlie Citrine, the protagonists of those later books, created what is now commonly thought of as the Bellow hero: hyperarticulate, rueful, sentimental, intellectual, urban, Jewish—and in all these ways recognizably versions of Saul Bellow. The plot of Herzog, with its adulteries and cuckoldries, corresponds very closely to what Bellow lived through during the time he was writing Henderson the Rain King and seeing it published.

Advertisement

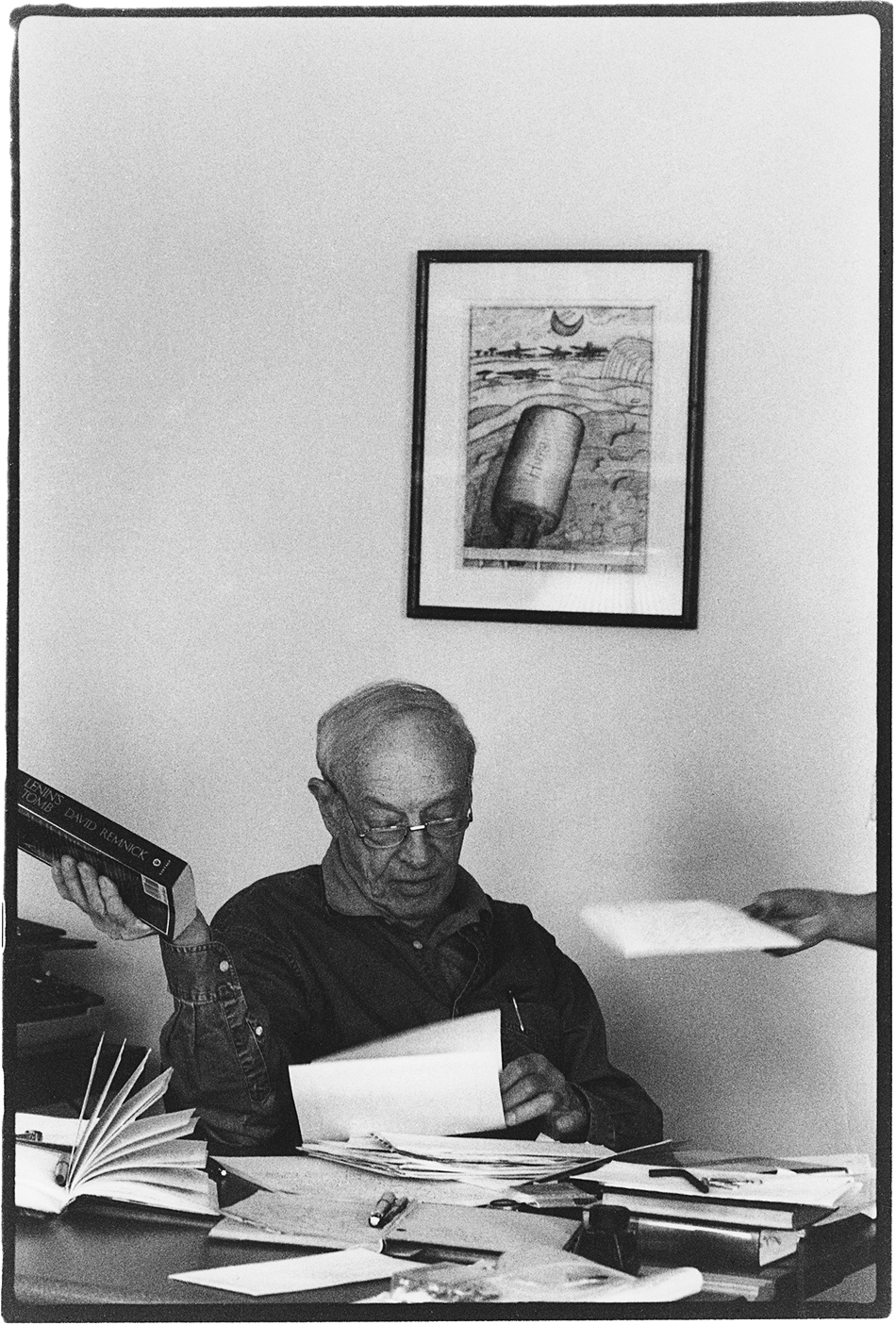

But when he wrote Henderson, Bellow had never been to Africa. His acquaintance with the continent was limited to his college textbooks in anthropology, from which he drew some of the details of Arnewi and Wariri tribal customs. Nor, of course, was he in any particular like Henderson—the heir to an old, prominent American family, a World War II veteran, an inarticulate man who speaks in slang and clichés, and a specimen of brute strength. The original inspiration for Henderson, rather, was Chanler Chapman, a descendant of the Astors and John Jay, who was Bellow’s landlord in Barrytown, New York, when he taught at Bard College in the 1950s. (This might make Bellow and his second wife, Alexandra Tschacbasov, the inspiration for the bookish couple who abandon Henderson’s guest house because he refuses to winterize it, leaving their cat to his tender mercies.)

Yet when Bellow was asked by an interviewer which of his characters was most like him, he named “Henderson—the absurd seeker of high qualities.” And it is true that Henderson, despite his exterior, has a Bellovian heart—which is to say, a heart tormented by yearnings. In the most famous sentences of the novel, Henderson describes the pulsation at the heart of his inner turmoil:

Now I have already mentioned that there was a disturbance in my heart, a voice that spoke there and said, I want, I want, I want! It happened every afternoon, and when I tried to suppress it it got even stronger. It only said one thing, I want, I want!

And I would ask, “What do you want?”

But this was all it would ever tell me. It never said a thing except I want, I want, I want!

If Henderson were Herzog or Citrine, he might explain that this “I want” is a version of what Descartes and Leibniz called conatus, the innate tendency to motion and persistence that characterizes being; or what Schopenhauer, more darkly, referred to as Will, the force of self-assertion that underlies everything in Nature. But the tragicomedy of Henderson, as Bellow conceived him, is that he is wholly inarticulate before this “I want,” unable to trace its intellectual genealogies or smother it in concepts. All he can do is experience it, and for him that means experiencing it bodily. Over and over again, Bellow suggests that thought and emotion, for Henderson, are immediately physical processes, in a way that approaches synesthesia: “moments when the dumb begins to speak, when I hear the voices of objects and colors.”

T.S. Eliot complained that modern poets had lost the ability to feel their thoughts and think their feelings, but that is just what Henderson does: “Certain emotions make my teeth itch…. When I admire beauty I get these tooth pangs, and my gums are on edge.” Likewise, he judges people’s character through their bodily appearance, as when he meets Queen Willatale: “You will understand what I mean, perhaps, if I say that the flesh of her arm overlapped the elbow. As far as I am concerned this is the golden seal of character.” Henderson seems to live in a state before the dissociation of mind and body, which is the typical complaint of the modern intellectual. This makes him just the right man to receive Dahfu’s teachings about physiognomy, with their quaint pre-modern air, their evocations of humoral theory and phrenology.

The intensity of his desire is a curse to Henderson, making it impossible for him to live peacefully with his wife and children and neighbors. But it is also the seed of his salvation, because it keeps him from falling into the condition that Bellow suggests is wholly fatal—sleep. One of the refrains of the novel comes from Shelley’s poem “The Revolt of Islam”: “I do remember well the hour that burst my spirit’s sleep.” The words haunt Henderson, who describes himself as a man “who had to burst the spirit’s sleep, or else.”

Advertisement

This obscure desire carries him first to Africa and then, crucially, into the remote interior, where he leaves behind his friend Charlie, whose elaborate gear and camera equipment threaten to come between Henderson and the direct experience he seeks: “my object in coming here was to leave certain things behind.” This is also a journey back in time, as Henderson encounters African tribes whose way of life reminds him of the biblical patriarchs: “Hell, it looks like the original place. It must be older than the city of Ur,” where Abraham is supposed to have been born.

To understand Bellow’s treatment of Africa and Africans, it’s crucial to remember that Henderson approaches them in the role of a seeker, almost a supplicant. Of course, to treat a continent and its people as though they are holdovers from a pristine past is itself a form of Orientalism. There’s no question that in this novel the Arnewi and the Wariri are made to play a role in the psychic drama of a modern Westerner, rather than being seen on their own terms. It is notable, for instance, that we never learn what country Henderson is actually in; though he is traveling through an Africa on the cusp of decolonization, the peoples he encounters seem to exist outside history and politics. (This is true even though, we learn, King Dahfu spent time in his youth studying at the American University in Beirut.) And there are moments in Henderson that will set anyone’s racial antennae on edge—above all, the stereotypical pidgin-English spoken by many (though not all) of the Africans: “Me here too, sah” and the like.

But the intention of the novel is plainly the opposite of racist. Its attitude toward race can be summed up by Henderson’s observation about Dahfu: “Of course the king’s extreme blackness of color made him fabulously strange to me. He was as black as—as wealth.” In thus portraying Africa as a home of spiritual wealth—of ancient, sacred wisdom that modern America has lost—Bellow treats it with the kind of fictionalizing reverence that other seekers bring to, say, Tibet. There is something very American about this tendency to insist that other lands will provide what our own lacks, as Henderson himself recognizes late in the novel:

There are guys exactly like me in India and in China and South America and all over the place. Just before I left home I saw an interview in the paper with a piano teacher from Muncie who became a Buddhist monk in Burma…. It’s the destiny of my generation of Americans to go out in the world and try to find the wisdom of life. It just is.

It’s easy to imagine Henderson’s teenage daughter Ricey, who gets expelled from boarding school and rescues an abandoned infant, growing up to become a flower child and setting out for an ashram in Rishikesh, like the Beatles.

But Henderson himself is not just following a trend, and if he is in flight it is partly because he is being pursued by ghosts. Henderson is obsessed with death, as he says again and again, because he has seen so much of it: “Not that the dead are strangers to me. I’ve seen my share of them and more.” Though we hear only occasionally about his experiences in World War II, it’s crucial to remember that Bellow places his protagonist at one of the bloodiest, most terrible battles of the war—Monte Cassino, where the American army struggled to dislodge the Germans from their defensive line near Rome. Monte Cassino was the site of a monastery founded by Saint Benedict in the sixth century AD, which ended up being destroyed by American bombs. By placing Henderson just here, at a place where the spiritual beginnings of the West were destroyed by what the West had become, Bellow seems to want him to inherit all the despair and dislocation of the postwar world: “Of course, in an age of madness, to expect to be untouched by madness is a form of madness.”

The Africa Henderson discovers, then, is not intended to be an accurate portrait of a place; it is, rather, the landscape of his quest. (“As I was a turbulent individual, I was having a turbulent Africa,” as he puts it.) This is a quest for wakefulness, or, to use a word that is one of the novel’s favorites, for reality. Yet reality turns out to be a slippery thing for Henderson, always turning into its opposite. Early on, before he even gets to Africa, he informs his wife during an argument, “I know more about reality than you’ll ever know. I am on damned good terms with reality, and don’t you forget it.”

Yet the reality he knows is wanting and suffering, and once in Africa he begins to suspect that if his reality is so soiled, it may be unreality he is really in need of. For it is a hallmark of the modern era that all the beautiful things earlier generations saw as the ultimate realities—God, providence, resurrection, cosmic justice—now appear unreal to us; whereas everything we honor as most real turns out to be frightening and sordid—death, void, chaos, purposelessness. In such a world, to voice an old hope—like a belief in the resurrection of the dead—is to sound fatuous or mad, as Henderson does when he declares, “For it so happens that I have never been able to convince myself the dead are utterly dead. I admire rational people and envy their clear heads, but what’s the use of kidding?”

In all his work, Bellow is hospitable to this kind of irrationalism. In later novels, the anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner would serve his purpose; in Henderson, as we have seen, he plays with premodern ideas of biology. His justification is simple: if the world reason has made is impossible for human beings to live in, perhaps we need to explore the unreasonable if we are to be happy. “Could I say that the world, the world as a whole, the entire world, had set itself against life and was opposed to it—just down on life, that’s all—but that I was alive nevertheless and somehow found it impossible to go along with it?” Henderson asks. If so, then reality, a word that for us has a cold, reproving sound—as in, “you’d better grow up and face reality”—may really be unreality, and vice versa. “There is that poem about the nightingale singing that humankind cannot stand too much reality. But how much unreality can it stand?” Henderson demands. (He is thinking of Eliot’s “Burnt Norton”—“Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind/Cannot bear very much reality.” One begins to realize that even Henderson, Bellow’s least intellectual hero, has actually read a good deal.)

There is only one way to guarantee that what we experience is real, is truth: it has to hurt, in the way all growth and education hurts. In another of the novel’s famous passages, Henderson recalls an accidental injury:

Beside my cellar door last winter I was chopping wood for the fire—the tree surgeon had left some pine limbs for me—and a chunk of wood flew up from the block and hit me in the nose. Owing to the extreme cold I didn’t realize what had happened until I saw the blood on my mackinaw. Lily cried out, “You broke your nose.” No, it wasn’t broken. I have a lot of protective flesh over it but I carried a bruise there for some time. However as I felt the blow my only thought was truth. Does truth come in blows? That’s a military idea if there ever was one.

“It’s too bad, but suffering is about the only reliable burster of the spirit’s sleep,” he confirms later on. This is the lesson of the first trial in Henderson’s quest, when he arrives among the cattle-herding Arnewi people and finds their land under a blight: frogs have polluted their water supply, making it impossible for them to water their cattle. It’s the classic premise of the Grail King legend, in which a suffering land must be redeemed by healing its suffering king—a legend well known to Bellow as a student of anthropology, and to a generation of readers through James Frazer’s The Golden Bough and its reflection in Eliot’s The Waste Land. (Clearly enough, Bellow was conducting a struggle with Eliot and everything his cultural pessimism meant for the modernist generation—what Bellow calls, in Herzog, “the commonplaces of the Wasteland outlook.”)

Henderson is challenged to prove that he is the champion the Arnewi need by wrestling with their prince, Itelo, and thanks to his bulk he wins handily. But this victory, Bellow shows, comes too easily for Henderson, who will not see enough truth until he has received enough blows. The quality he desires is what the Arnewi call “Bittahness,” which he sees incarnated in their queen Willatale:

A Bittah was a person of real substance…. She had risen above ordinary human limitations and did whatever she liked because of her proven superiority in all departments.

But his premature victory does not fill Henderson with this kind of contentment; instead, it gives him a dangerous hubris. Having defeated Itelo through mere force, he brings mere force to bear on the frogs, blowing them up with an improvised bomb—which ends up wrecking the whole reservoir, leaving the Arnewi waterless.

“Why for once, just once!, couldn’t I get my heart’s desire?” Henderson laments. He has yet to learn that getting what you want is not the way to still the voice that says “I want,” for desire always has another object, another goal. To see the true path, he needs a teacher, a sage—or, perhaps, a therapist. For it is unmistakable that once Henderson arrives among the Wariri, the relationship that develops between him and King Dahfu is remarkably like that between a patient and an analyst. And just as psychoanalysis commands us to confront our repressions and fears, rather than bury them, so Dahfu forces Henderson to come face to face with the greatest terror of all: the lion.

The scene in which Henderson first confronts Atti the lion, in Chapter 16, is perhaps the most powerful in the novel, partly because of Bellow’s almost supernatural gift for physical description. This, one feels, is just what it would be like to come face to face with a lion:

The snarls of the animal were now as sharp as thorns to me, and blind patches as big as silver dollars came and went before my eyes…. She stood well above our hips in height. When he touched her her whiskered mouth wrinkled so that the root of each hair showed black…. I was gripping the inside of my cheek with my teeth, including the broken bridgework, while my eyes shut, slowly, and my face became, as I was highly aware, one huge mass of acceptance directed toward fate. Suffering. (Here is all that remains of a certain life—take it away! was implied by my expression.)

What is so terrifying in Henderson’s meeting with the lion is not simply the danger of being clawed to death. Much as Bellow deplored symbol-hunting in literature, there is no mistaking the symbolic weight of Atti, who embodies all the primal violence that Henderson must confront within himself. By facilitating this encounter, Dahfu plays the role of doctor, even using a therapist’s vocabulary: “It is true I am attempting rapid progress. But I wish to overcome your preliminary difficulties in quick time.”

In particular, these scenes are a sly parody of and homage to the radical therapeutic techniques of Wilhelm Reich, which Bellow himself had undergone in the early 1950s. Reich, a heretic from Freudian principles and something of a lunatic himself, believed that the key to mental health was to break down one’s “characterological armor” and build up the primitive orgasmic energy he dubbed “orgone.” One way of doing this was to sit in a telephone-booth-sized box built to Reich’s specifications, the infamous “orgone accumulator.” For a time, Bellow installed one of these boxes in his Queens apartment, and engaged in Reichian techniques like primal screaming (considerately, he put a handkerchief in his mouth to stifle the sound). So too with Henderson: “certain words crept into my roars, like ‘God,’ ‘Help,’ ‘Lord have mercy,’ only they came out ‘Hooolp!’ ‘Moooorcy!’”

Still, “Henderson is not Reichian confusion, but comedy,” as Bellow wrote to the critic Leslie Fiedler. And it’s not necessary to have heard Reich’s name to understand what Bellow is doing in these frightening, liberating scenes. What is important is the way that, here as throughout the book, Henderson remains open to the irrational, and to ways of thinking about life and nature that modern science would scorn. (“In college we had laughed Lamarck right out of the classroom,” Henderson recalls, but Bellow would not be so quick to laugh.) Following Dahfu’s theory of physical types, Henderson comes to believe that his unhappy life has made him literally piggish—after all, he was once a pig farmer—and that to be redeemed he must become lionlike. “She will make consciousness to shine. She will burnish you. She will force the present moment upon you,” Dahfu assures Henderson.

Can a lion do all that? Bellow leaves the answer unclear; the novel’s denouement returns Henderson to civilization, having seen both the good and the evil sides of the lion’s power and example. But there is no better description of what Henderson the Rain King, like all of Saul Bellow’s best work, does supremely well. It makes consciousness shine; it burnishes; it forces the present moment upon you. Lacking a lion, you can turn to Bellow as to few other modern novelists for the feeling of wisdom, the sensation of insight, which is rarer and more precious than any doctrine: “The universe itself being put into us, it calls out for scope. The eternal is bonded onto us. It calls out for its share.”

This Issue

December 6, 2012