At the opening ceremony of the new Queens Family Courthouse in February 2003, New York State Chief Judge Judith Kaye said,

For too long, families with cases in Queens Family Court have been subjected to anything but dignified surroundings, but now, with the opening of this new justice complex, they will be in a place that will inspire confidence and respect again.

The governmental press release that quotes Kaye goes on to praise the building’s “beautiful five-story atrium” and to conjecture that “waiting areas with exterior views and maximum exposure to natural light should make the long waiting periods less stressful to families.” A non-architectural solution to the problem of chronic lateness was evidently never contemplated. Long waiting periods are a fundamental, almost sacred part of the legal system, indispensable to the administration of justice.

Accordingly, the architectural firms of Pei Cobb Freed and Gruzen Samton took it as one of their highest priorities—perhaps the highest priority of all—to make the corridors where people wait interminably as pleasant as possible. In The New York Times of July 6, 2003, Ian Bader of Pei Cobb Freed recalled the agonizing that went on at the firm over the facing pairs of wooden benches that line the corridors. “The first dimensional decision was, what is a comfortable distance face-to-face?” Bader said. Eight feet was finally arrived at: “close enough to accommodate large amounts of seating but not so close that it would make strangers feel uncomfortable facing one another.” “It’s not that architecture can solve the problems of the people who come to the building,” Bader added modestly—too modestly, perhaps.

When I attended the criminal trial at Queens Supreme Court of Mazoltuv Borukhova and Mikhail Mallayev for the murder of Borukhova’s estranged husband Daniel Malakov, all my attempts to speak to Borukhova’s sisters and mother were rebuffed; they refused to have anything to do with me. But in Queens Family Court, when I took a seat on the bench opposite Natella, Sofya, and Istat Borukhova, they did not rebuff me. Under the spell of Pei Cobb Freed’s dimensional magic, they began to accept my overtures, and to see me as someone to whom they could tell their side of the terrible story, though always with caution and reserve.

One day I arrived in the waiting corridor to find Natella, a mother of six, with a little rosy-cheeked boy of two on her lap. She was playing a game with him: she would uncurl and kiss his fingers one by one, then curl them up again, as he crowed with delight. The Malakov family’s grim belief that the Borukhova sisters and mother were accomplices in the murder (the Malakovs did not hesitate to share this theory with journalists) was hard to credit in the light of such a scene. On the other hand, wasn’t tender maternal attachment a crucial element of the case against Borukhova, the putative motive for her desperate act?

In April 2008, over the protests of her maternal relatives, Borukhova’s daughter, Michelle Malakova, was sent to live with her paternal uncle Gavriel (a brother of her murdered father) and his wife Zlata. In July 2008, seven months before the murder trial, she began making monthly visits to her mother at Rikers Island. She came accompanied by a social worker—usually Eliana Cotter of OHEL, an Orthodox Jewish foster care agency—and an interpreter. The purpose of the interpreter was to make sure that Borukhova said nothing “inappropriate” when she spoke to the child in Russian. Michelle sat on her mother’s lap and Borukhova told her stories and played games with her and asked her about her life. In the “progress notes” she was required to keep, Cotter observed the warmth and closeness between mother and child, and the child’s sadness on leaving.

Gavriel and Zlata had been firmly told by the Administration for Child Services (ACS) not to speak about the murder to or in front of Michelle, and they had obeyed, as had Daniel’s brother Joseph and sister-in-law Natalie. But Joseph and Natalie’s youngest children, Julie and Sharona, age six and seven, were under no such constraint. Their sharp ears had picked up what was obviously talked about all the time at home, and when they played with Michelle they saw no reason not to inform her that her mother was in jail and that she had killed her husband. This was two months before the prison visits began. On May 9, Cotter wrote that Michelle asked “where BM [her birth mother] is and said Julie and Sharona think she’s in jail. She said jail is ‘a very dark place.’” Cotter confirmed that Borukhova was in jail, but that “jail is not dark and BM has everything she needs.” She explained that “sometimes when people are waiting for court they have to wait in jail.” On May 22, Cotter wrote that on the way home from a therapy session,

Advertisement

Michelle asked why BM was in jail and if she did something wrong. CP [the “case planner,” Cotter herself] asked what if Michelle thought BM did something wrong, and Michelle said “Yes, she killed Danik.” She said her cousins Julie and Sharona told her this. Michelle then said BM couldn’t have killed him because she didn’t have a gun. CP asked if Michelle saw what happened. Michelle said that she did and a man shot BF. Michelle started crying and said she missed BM and wanted to see her.

Michelle had been speaking with Borukhova on the telephone since her incarceration, but these conversations were not a success. Since prisoners can only call collect, Borukhova would call during Michelle’s visits with her maternal grandmother and aunts and cousins, and Michelle talked to her reluctantly. She did not welcome the interruption of the games she was playing with the cousins. This was not callousness or unlovingness. Play is the serious business of childhood, its work. For Michelle, from whose life almost everything familiar had disappeared, play was a remaining structure that she grasped at as if holding on to a ledge over an abyss. She played harder than most children do. (Sharona and Julie had noticed this and commented on it to me when I met their family in the fall of 2009.) Michelle articulated her ambivalence to Cotter about her mother’s calls: “‘Sometimes I don’t want to talk when she calls. I don’t like that she calls all the time.’ CP asked if Michelle wanted BM to call during every visit or only sometimes. Michelle replied, ‘Only sometimes.’”

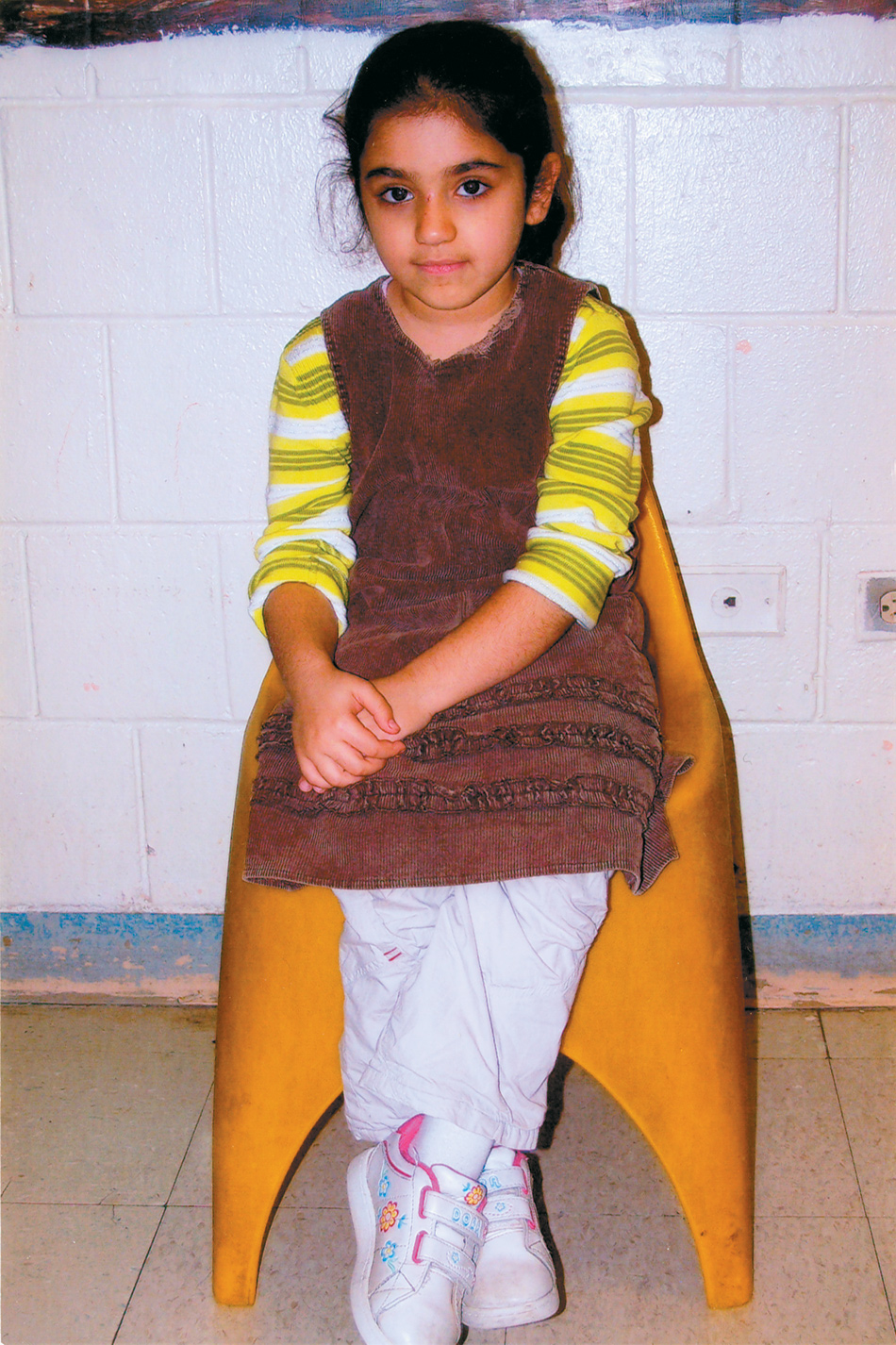

The visits with the maternal relatives were occasionally held in one of the aunt’s apartments (a few times Michelle was allowed back into her own old apartment), but usually took place at a social agency. In her notes, Cotter would list the names of the cousins who came—Yocheved, Liana, Nerya, Batya, Eliot, Milana, and Moshe—and the games they played with Michelle—Simon Says, Red Light Green Light, Mother May I? (!!!) The grandmother always brought home-cooked food for Michelle, who often, in her eagerness to play, heedlessly brushed her aside. Cotter noticed the child’s rudeness to her grandmother with increasing disapproval and finally intervened. “MGM repeatedly offered Michelle food but Michelle ignored her,” she wrote. “CP redirected Michelle to respond when people talk to her and Michelle said ‘I don’t want any.’ CP prompted her to tell this to MGM in Russian. At first she pretended she did not know how then she complied. MGM accepted Michelle’s response and stopped pressuring her to eat.”

Cotter’s nice resolution of the impasse between the heedless child and the Jewish grandmother is an example of what is called “problem solving” in social work argot. But when Michelle’s therapist, a social worker named Richard Maisel, used the term in a conversation with Cotter in November 2008, about an impasse between Michelle and Gavriel that he was attempting to cut through, there was no such easy fix.

Michelle started to see Maisel in June 2008. Gavriel and Zlata were dissatisfied with the previous therapist, Alla Weinstein, and wanted someone with “a more direct and honest and less evasive therapeutic approach.” Maisel gave them what he thought they wanted. In an early session, as Zlata told Cotter on July 13, “Mr. Maisel informed Michelle of the reason BM is imprisoned”—knowledge that Michelle naturally resisted and denied. But Maisel soon realized that what Gavriel and Zlata wanted from him was not only that he work with Michelle to help her face a tragic reality, but that he work on her to behave better at home.

Ever since Michelle went to live with Gavriel and Zlata in April she had displayed what they called “oppositional behavior.” She told them that she hated them and wanted to be with her maternal relatives. She refused to do her homework. By November, she was a holy terror, crying and screaming and hitting classmates at school and stealing food from them. Maisel saw that a good part of the problem was the foster father, who was locking horns with the child over every issue, and driving her to despairing fury. He would stand over her as she did homework until she balked and said she couldn’t do anymore. Maisel told Gavriel (Cotter reports) that “getting into a struggle of wills is useless, and as Michelle gets frustrated she may start purposely giving the wrong answers.” Cotter continues :

Advertisement

He suggested instead to try to work with her…try to join her as an ally, instead of forcing her as an adversary. He suggested taking a brief break or switching to another subject. FF [foster father] nodded and smiled, but Richard did not know if he was really listening to the conversation.

Cotter goes on:

FF discussed another situation which Richard identified as a struggle of wills…. In the morning when Michelle is having cereal, FF wants to force her to have bread with it. FF says this is very important because otherwise she is hungry later, eats her snack on the bus, and then takes food from others…. Richard tried problem solving, and suggested that maybe Michelle is just not hungry first thing in the morning and only becomes hungry a little later. Richard suggested packing her an extra snack to alleviate her hunger, and explain that if she doesn’t eat it then she can bring it home. Richard said this is a concrete solution to a relatively easy problem. FF said, “Ok, I may try that, but she’s getting fat.”

Gavriel—as might be expected—can’t suddenly turn himself into an empathetic adult. Maisel contemptuously characterizes him in Cotter’s report as “‘an undereducated, limited parental body’ getting into ‘struggles of will’ with a six-year-old.” When he stops bringing Michelle to her appointments and Cotter tells him that the child needs therapy “to process the numerous traumatic events of her life,” he retorts that

some of Michelle’s oppositional behaviors are not due to her traumatic history but are due to the fact that she was initially raised in a very permissive and undisciplined manner and doesn’t like having rules and responsibilities. He stated that [her father Daniel] told him of [Borukhova’s] parenting style and that Michelle was very spoiled.

Always looking for reasons unrelated to themselves for Michelle’s disruptive unhappiness, Gavriel and Zlata now blame the visits with her maternal aunts and cousins for Michelle’s worsening behavior. Zlata tells Cotter that after visits with the aunts and cousins, Michelle defiantly tells her “she wants to live with ‘mommy’s side,’” and becomes ungovernable. After her visits to Borukhova at Rikers (and, post-conviction, at Bedford Hills), she similarly “acts out.” Of course, what Michelle is enacting is her sense of the difference between the warm, accepting Borukhovas and the chilly, censorious Malakovs. Her exposure to the familiar loving ways of her mother and grandmother and aunts can only sharpen the contrast between the two family styles and set off her anger at being forced to live with the paternal side.

On September 16, 2009, at a hearing in Queens Family Court, Judge Linda Tally ruled—upon the urging of David Schnall, Michelle’s law guardian—that Michelle’s visits to her maternal relatives be reduced from three times a month to twice a month. Schnall said that the child had “adjusted fabulously” to living with Gavriel and Zlata but that after visits with the maternal relatives she is confused about “where her home is and where it is going to be.”

The name David Schnall will be familiar to readers of my book about the Borukhova/Mallayev criminal trial.1 He was the witness who testified against Borukhova and incautiously talked to me, for nearly an hour, about his conspiracy theories—theories so nutty that I felt compelled to breach my journalist’s neutrality and give the defense attorney my notes of the conversation, in which he said, among other things, “We’ve been living under the ten planks of the Communist Manifesto. We’re a Communist country,” “The male sperm count is down 75 percent. We’re almost completely sterile,” and “Everything I’ve said is not opinion, it’s fact. THEY control the world.” (In court the next day, Borukhov’s lawyer Stephen Scaring presented a motion to the judge, citing my notes and asking that Schnall be recalled for cross-examination about his mental health; the judge, who favored the prosecution, turned down the motion.)

The position of law guardian was created in the 1960s to assist children who were in trouble with the law. But when the assistance was extended to children caught in the middle of custody disputes, something untoward (though perhaps predictable) occurred. The law guardian could no longer simply advocate for his child client. He was forced, in the name of the doctrine of “the best interests of the child,” to advocate for one or another parent—who was not necessarily the parent the child wished to live with.2

When Schnall was appointed Michelle’s law guardian in 2005, he almost immediately favored the father and took against the mother. Of the people who hate Borukhova, he was arguably the most passionate and virulent hater of all. At the “imminent risk” hearing two days after the murder to determine whether Borukhova could regain custody of Michelle, he seemed almost consumed by his spite and dislike. He would not rest until each witness confirmed his characterization of Borukhova as a monster. When a court-appointed psychologist named Paul Hymowitz was questioned by the ACS attorney about his impression of Borukhova, he merely said he found her strange and her accusations of sexual abuse “outlandish” and “gruesome.” But in his cross-examination Schnall pushed Hymowitz until he agreed that she was a sociopath, “lying without conscience.” Schnall’s cross-examination of Borukhova herself was so brutal that her lawyer, Florence Fass, was moved to protest: “This isn’t cross, this is badgering.” When Tally issued her final ruling—that Borukhova had subjected Michelle to “emotional neglect” and could not have her back—she credited Schnall with influencing her: “The Court gives substantial weight to his recommendations,” she said.

That Schnall was not furthering the interests of Michelle was clear, and became even clearer during Borukhova’s criminal trial, when Schnall had to admit, under Scaring’s cross-examination, that he had never spoken with his child client. In Family Court, through a succession of lawyers, Borukhova tried to get Schnall removed, but to no avail. Motions asking for his disqualification on the ground that he testified against Borukhova at the murder trial and that he was unstable were all turned down by Judge Tally.

Today, Schnall is no longer Michelle’s law guardian—not because Borukhova’s attempts to remove him succeeded, but because he was arrested in March 2012 for tax evasion. According to a press release entitled “Five—Including Two Attorneys—Charged with Cheating New York State in Tax Fraud Schemes,” issued by the office of the Queens district attorney, Richard Brown (the DA who had prosecuted Borukhova), Schnall was charged with “second-degree criminal possession of stolen property…third-degree criminal tax fraud, failure to file a return or report and failure to pay tax.” The press release continued, “Schnall, who faces up to 15 years in prison if convicted, was arraigned in Queens Criminal Court on March 29, 2012, and released on his own recognizance.”

Schnall did not go to prison. On May 1 he returned to Queens Criminal Court with a lawyer and, in a plea bargain with the DA’s office, was allowed to pay the $80,837 he owed and to change his original plea of not guilty to a plea of guilty to the misdemeanor that remained after the DA withdrew the more serious charges. He was sentenced to a “conditional discharge,” “which means,” Judge Pauline Mullings told him, “if you were to commit another crime within the next year, this case could be restored to the calendar and you could be resentenced to up to a year in jail.” By then Schnall had resigned as Michelle’s law guardian and later in the month he was quietly removed from the roster of law guardians by the Administration of the New York State Court System.

At the hearing of September 16, 2009, Tally approved ACS’s motion that Borukhova be designated a “severely abusive” parent because she had hired someone to murder her husband in the presence of her daughter. This was not an idle exercise in name-calling. It was the foundation on which Borukhova’s permanent loss of her daughter would stand, the TRP—termination of parental rights—toward which the hearings lumbered (thus their name “permanency hearings”).

Borukhova had a legal right to be present, but after a while she stopped coming and appeared in the courtroom only as a small figure on a video screen listening and occasionally speaking from Bedford. Borukhova waived her right to be in the courtroom because when she came she had to spend a week at Rikers Island; the bus back to Bedford came only once a week. Along with its harsh conditions, Rikers did not provide the kosher food that was the only food Borukhova would eat. (During her year at Rikers waiting for trial, she had subsisted on a diet of peanut butter sandwiches from the commissary.) Sometimes the two-way audio connection failed—Borukhova couldn’t hear what was being said in the courtroom—and Tally would peevishly point out that “she is free to come to Family Court anytime she wishes to come…but she doesn’t wish to do so.”

Tally made no effort to hide her feelings about Borukhova. She and Schnall were in accord. She did not accept all the restrictions on Borukhova and her family he proposed, but in general she followed his harsh counsel. She apparently shared his liking for the Malakovs and his—and ACS’s and OHEL’s—refusal to acknowledge that Michelle’s placement with Gavriel Malakov was a disaster.

On February 23, 2011, Tsipi Gottesman, the social worker who had replaced Eliana Cotter as Michelle’s shadow, wrote at unusual length about a visit to the Bedford prison that she and the child—now eight years old—had made on February 18. Like Cotter (and Martinez before her), Gottesman could not but be struck by the extraordinary rapport between mother and child. The delight of the child and the regally assured manner of the mother were noted by her as they had been by her predecessors. The visit lasted three hours, and during the last hour, as had become customary at Bedford, the maternal grandmother and one of the maternal aunts and a cousin joined the mother and child for play and art projects. At the end of the visit, as she was putting on her coat, Gottesman writes, “Michelle reported to BM that she ‘gets hit all the time.’” Gottesman continues:

BM asked Michelle who hits her and she reported “they do when they want me to go upstairs to go to sleep, grandma and grandpa do it.” BM asked who? Michelle responded it was her foster father.

Gottesman notes that Borukhova asked no further questions, but “looked at MA and CP in alarm.” During the drive back to the city, Gottesman questioned Michelle closely and Michelle reiterated that her foster father hit her:

CP asked what does he use to hit her—Michelle reported that he hits her on her back with his hand. CP asked Michelle when was the last time Gavriel did this. Michelle responded that he does it all the time and the last time was this morning. Michelle reported that he does the same to the other children and FM does not stop him. Michelle reported that the Foster Mother does not hit her. CP asked if she ever spoke to FM about this and Michelle reported “of course not.” CP asked Michelle if she ever asked Gavriel to stop hitting her and Michelle shrugged her shoulder and began to look extremely sad. Michelle reported that she’s afraid of Gavriel…. CP asked Michelle if she could see her back to check if there are any bruises. Michelle reported that I cannot look at her back. CP asked Michelle if it hurts after Gavriel hits her back. Michelle reported “Of course.” Michelle appeared very sad and afraid.

Gottesman asked the driver to pull over to the side of the road and called Chaya Surie Malek, her supervisor at OHEL, who then called the OHEL attorney James M. Abramson. Abramson knew that two days later Michelle was scheduled to travel to the Dominican Republic with Gavriel and Zlata and other members of the Malakov clan, and, as he would testify in Family Court a month later, “the agency concluded that they could not in good faith let the child go to the Dominican Republic, beyond the jurisdiction of this court, for ten days, given the information that had been made available to it.” So he instructed Gottesman not to return Michelle to Gavriel and Zlata, but to take her to a “respite home.” Once again, fortune smiled on Michelle. The wonderful Broders, the “non-kinship” foster parents with whom she had happily lived for five months before coming to Gavriel and Zlata, were able to take her in and she was driven to their house that afternoon. She never lived with Gavriel and Zlata again.

Tally was fit to be tied when she learned of these developments. In Family Court on March 14, 2011, she lashed out at Abramson:

Mr. Abramson, maybe you can explain to the Court what has been going on, that a child that is before this Court for several years now, the child apparently was removed from an uncle’s home, no one saw it fit to notify this Court. No applications were made, the child was simply just removed, what is going on?

As Abramson began to tell the story of the removal, Tally tore into him further: “Did anyone think to go to Family Court and file something, people come for all different reasons to Family Court. We’re now freelance artists that we do whatever we wish to do?”

Abramson defended himself as best he could. He had brought a report to court, signed by Tsipi Gottesman and Chaya Surie Malek, in which OHEL finally and fully acknowledged that its efforts “to maintain the stability of the foster care placement” were misguided and that Michelle should under no circumstances be put back into Gavriel and Zlata’s keeping. The tone of the OHEL report is one of ill-concealed hostility toward the once-favored foster parents. “It is important to note,” Gottesman and Malek write after retelling the story of the removal, “that the Malakovs returned from vacation on Sunday, February 27th, 2011. Sup left Mr. Malakov a message on Monday, 28th. He did not return the Supervisors call. Supervisor had to call again on Tuesday. Mr. Malakov did not ask how Michelle was doing.”

After citing various instances of “concerns” with the Malakov family—among them the missed therapy sessions; the extraction of a tooth that could have been saved if the foster parents had not waited five months before taking the child to the dentist after a cavity had been discovered; Gavriel’s habit of pinching Michelle’s cheeks so hard that he left marks (the child told of this daily practice when Borukhova noticed the marks during a prison visit); a previous accusation by Michelle that “Mr. Malakov hits her with his hand”; and Gavriel and Zlata’s inability to make up their minds about whether to adopt Michelle or not—the report recommends an “immediate transfer” of Michelle to her aunt Sofya, who is “attentive, nurturing and interactive,” has a “strong connection” to her niece, and has no reservations about adopting her.

In addition to the OHEL report, Abramson submitted a report from Jacob Adler, the therapist who had replaced Maisel, and had been treating Michelle for over a year. (Maisel quit after Gavriel threatened to sue him.) Adler, too, recommended that Michelle go live with Sofya, “a much warmer and sensitive individual than Zlata and Gavriel.” Adler’s view of Zlata and Gavriel was much like his predecessor’s:

I feel that although they were concerned about Michelle, they did not express a strong sense of warmth toward her. They were consistently concerned about her academic performance, but in my opinion there was a limited understanding of her emotional life in spite of my attempts to address these issues.

Adler had seen Michelle four days after her move to the Broders and observed that she was “happy, cheerful and better kempt and put together” and evidently living “in a much more relaxed and emotionally healthy environment.” Michelle confirmed to Adler that Gavriel regularly hit her on her back and added a new detail about her life with him and Zlata. “When questioned about her aunt she reported that Zlata would pull her hair when she did not behave.” Adler went on:

It is of utmost importance to note that Michelle is an excellent and highly credible reporter. I have never had any experience of her not being truthful. She is an intelligent young lady who may have been understandably guarded talking about Zlata and Gavriel while living in their home.

Tally had a different view of Michelle. Throughout the hearing of March 14 she made it clear that she did not believe the child. Gavriel had not availed himself of the chance to deny the charge at an Independent Review Fair Hearing. But as far as Tally was concerned, he didn’t have to. There seemed to be no doubt in her mind that Gavriel was innocent and that Michelle had made the story up at the instigation of her mother. “There has been nothing to substantiate these allegations, they haven’t been founded,” she said. “The Court hasn’t seen anything of substance other than the statements that Michelle has made to some, not to others, laughed about it to some, no indication that the child’s been injured, no injuries seen on the child’s back….”

Tally’s skepticism was not unreasonable. Michelle’s story—for all of Adler’s faith in her reporting—was wobbly. Her refusal to let Gottesman look at her back speaks against her. Worse yet is her initial little misstep—her original answer to Borukhova’s question that it was the grandparents who hit her “when they want me to go upstairs to go to sleep.” Borukhova’s “Who?” reads like a signal to the child that she had given the wrong answer. “Dear one, if you want to escape from your odious uncle, you need to say it was him,” the unspoken message seems to say. The child corrected course. From then on it was always Gavriel who hit her. The grandparents disappeared from the narrative. In their court report Gottesman and Malek omitted all mention of them, nor did they mention Michelle’s refusal to have her back examined. They wanted what Michelle wanted. She had given OHEL the chance to correct its mistake in placing her with Gavriel and Zlata, and OHEL leaped at it. Tally, for all her mutterings about Michelle’s untruthfulness and OHEL’s overreaching, had to concede defeat. She did not send Michelle back to Gavriel and Zlata; she allowed her to stay with the Broders, where she once again thrived.

But any sense of victory felt by Borukhova and her family was short-lived. Tally had no intention of giving the “killer family” any further quarter. When Michelle’s stay with the Broders ended (this time it was clear from the start that the placement was temporary), Tally was determined that she not go to Sofya, who “reeks of complicity in the murder,” as Schnall put it during one of his dire speeches in court. In spite of OHEL’s and Adler’s strong endorsement, the “attentive, nurturing” aunt was once again rejected, and the child was once again sent to the Malakovs, this time to her other uncle, Joseph. Sofya’s motions asking for custody of her niece were swatted away by Tally like annoying insects. You have no standing, she told Sofya’s lawyer, Cheryl Solomon. After one of these rebuffs, I asked Solomon what having no standing meant. “It means the judge hates you,” Solomon replied.

—This is the second of three articles.

This Issue

December 6, 2012

-

1

Iphigenia in Forest Hills (Yale University Press, 2011). ↩

-

2

In his powerful book What’s Wrong with Children’s Rights (Harvard University Press, 2005), Martin Guggenheim, a professor of clinical law at New York University, writes:

↩For most of my career, I have been a critic of the assumed value of providing counsel for children in custody proceedings. Time and again I have seen lawyers choosing for themselves what outcome to argue for on behalf of their child clients and gaining the advantage in the case for no other reason than that they became the recognized voice for the children’s interests. Even when the judge knows full well that the position the children’s lawyer is taking is really nothing more than the product of the lawyer’s personal views, judges give considerable weight to that lawyer’s position.