1.

Did the notoriously lavish displays of the Gilded Age, which showed off the advantages of wealth on a hitherto unimaginable scale, inspire criminal behavior on the part of some of those unlucky enough to have to work for an honest living? Willa Cather seems to have thought so. Her classic short story “Paul’s Case,” first published in 1905, plays on at least two meanings of the word “case.” Subtitled “A Study in Temperament,” it is a psychological case study of a high school misfit in modest circumstances who longs to indulge in what Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption.” Standing outside one of the grand hotels in Pittsburgh, to the doors of which he has secretly stalked an opera star, Paul imagines himself entering “an exotic, a tropical world of shiny, glistening surfaces and basking ease,” with “mysterious dishes…brought into the dining-room, the green bottles in buckets of ice, as he had seen them in the supper-party pictures of the Sunday supplement.”

But “Paul’s Case” is also an account of a criminal case. Whistling melodies from Gounod’s Faust, Paul steals money from the bank where he works in order to spend a few wild nights at the Waldorf, passing for one of the high-society blades he has envied his whole short life. After his debauch, he dreads the inevitable return to his bedroom in Pittsburgh with its pictures of John Calvin and George Washington on the wall, the recriminations of his remote and joyless father, and the drab lives of his well-behaved contemporaries. “It was a losing game in the end,” he concludes, “this revolt against the homilies by which the world is run.”

What if Paul had decided not to throw himself in front of a train, like that other Romantic rebel Anna Karenina, but instead had returned to Pittsburgh to pursue his revolt against the homilies? Certain features of Cather’s imaginary character—his Calvinist childhood, his extreme thinness, his habitual lying (“indispensible for overcoming friction”), his theatrical flair for costumes and grand gestures, his longing for money and glamour—uncannily resemble the unsettling figure at the center of Geoffrey C. Ward’s by turns amusing and appalling narrative A Disposition to Be Rich, with its believe-it-or-not subtitle that itself recalls the aggressive marketing of the Gilded Age. That Ferdinand Ward Jr., the conman who “ruined an American President” and “brought on a Wall Street crash,” happened to be the author’s great-grandfather renders the story all the more piquant.

It is well known, of course, that the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant was marred by incompetence and corruption. “Under Grant’s two administrations,” as Edmund Wilson colorfully observes, “there flapped through the national capital a whole phantasmagoria of insolent fraud,” including the Crédit Mobilier affair, the Whisky Ring, and the conspiracy of Jim Fisk and Jay Gould to corner the gold market. Historians have noted the strange disjunction between the consummately skilled general, so attentive to all details of strategy and personnel on the battlefield, and the oddly aloof president out of his depth. “One can hardly even say that Grant was President,” Wilson remarks, “except in the sense that he presided at the White House, where the business men and financiers were extremely happy to have him, since he never knew what they were up to.” Grant was “had” during his sojourn in office and after he returned to private life in 1877. “It was the age of the audacious confidence man,” Wilson observes, “and Grant was the incurable sucker.” None of those con men was more audacious than Ferdinand Ward Jr.

2.

Much later, in a letter from his cell in the state prison of Sing Sing, at Ossining, New York, Ferd Ward would ascribe many of his troubles in life to his rigid upbringing in the small town of Geneseo, in upstate New York. “I have felt in my own case,” he wrote, “the evil of too strict a religious training.” His parents were missionaries in India during the great age of offloading Protestantism to the remote regions of the world. Reverend Ferdinand De Wilton Ward was never quite at home in his postings, and holed up in his study to write self-righteous tracts and letters of complaint to the authorities back home. His wife, a more eager and idealistic supporter of the cause, ran a Christian school for girls. The Wards were appalled by the intransigent Hindus, with their multiple gods and their pestilence. “What do you think is the reason we leave our native country, come to your villages, and expend so much in the education of your children?” Ferdinand asked a group of Hindu priests. “Oh, it is your nature,” one of them answered, “just as it is the nature of the jackal to prowl abroad at night.”

Advertisement

Suffering from various exotic symptoms, the Wards aborted their mission in 1846 and settled in Geneseo. Reverend Ward was the kind of old-school minister who could draw a clear distinction between “sprightliness” and “levity.” He threw himself, always on the reactionary side, into sectarian battles over liquor, antislavery agitators, and other enemies of civilization—that “large budget of evils,” as a friend of his put it, “brought by the Erie Canal.” Frustrated in her own missionary longings, Mrs. Ward lapsed into depression and spent months away from home on water cures and other futile therapies.

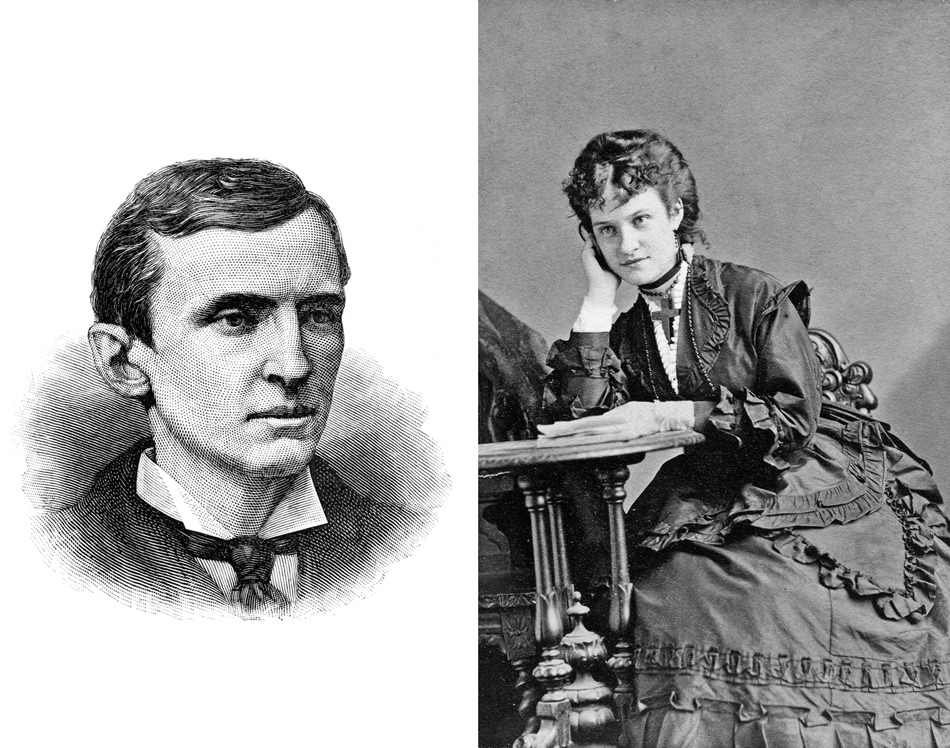

Three interesting children grew up in this narrow household. An older brother, Will, became a mining engineer, lectured at Oxford, and founded cities in the West. Sarah Ward moved to Philadelphia and married John Hill Brinton, a distinguished surgeon of Quaker background who had served on the battlefield with Grant. Brinton was an expert on gunshot wounds as well as

the world’s leading authority on the eerie phenomenon he called “frozen death”—the strange spectacle of soldiers who had been shot through the brain but whose bodies remained on horseback or in kneeling positions, sometimes clutching their pipes between their teeth, as if still living.

The Brintons were close friends of Thomas Eakins, who painted deeply felt portraits of both of these thoughtful, responsible people.

A third child, Ferdinand Jr., born in 1851 and “almost surely a surprise,” was perhaps more remarkable still. Even if he hadn’t been born the son of a minister, in a household where a nip of brandy was seen to bring down God’s holy wrath on the sinner, any parent might have been alarmed by the child. “It was increasingly clear within the family,” Geoffrey Ward writes, “that something more than weak eyes or the ‘nervousness’ and tendency to fall ill he had displayed since infancy was wrong with Ferdie.” He was, apparently, missing something at birth, but it wasn’t immediately clear precisely what it was. A conscience, perhaps? A sense of the rights and well-being of others? His mother futilely advised him, at age six, “Don’t spend your pennies for candy but give them all to Sunday School.”

While Will Ward fought with distinction and was imprisoned twice in the Civil War, and his father served as a chaplain at Gettysburg, Ferd, a teenager let loose on the home front, progressed from “unauthorized buggy rides” to shadowy misdemeanors that got him expelled from a series of boarding schools. Ward notes drily that Ferd “had begun to spend money that was not his.” A few years later, as though exacting revenge for his strict religious upbringing, he brazenly siphoned money from the Sunday school fund of a church for which he served as treasurer. Was Ferd a sociopath, a trauma survivor, or, as Geoffrey Ward suggests, a bit of both?

The cumulative trauma of his childhood—his father’s remoteness, his mother’s depression, the tension between his parents and between them and many of their neighbors, the constant dread of death and damnation that hung over the dark parsonage—evidently helped convince him early on that no matter what happened he was always a victim, perpetually blameless.

A move to New York in 1873, where it was thought that Will Ward might keep an eye on him, gave Ferd a wider stage for chicanery. He was hired as a clerk on the Produce Exchange in Lower Manhattan, but his first major step to advance his career was to marry an heiress named Ella Green. He pocketed his father-in-law’s fortune at the time of his convenient death three months after the wedding, and approached the dead man’s best friend, James D. Fish, president of the Marine National Bank, for advice in investing. Ferd claimed to be pursuing a lucrative trade in buying and selling certificates for the Produce Exchange, and Fish was impressed with his initiative.

In fact, there were no certificates and Fish asked no questions. Ward simply paid investors large returns from subsequent investments by others. Supposed deals in surplus flour were also imaginary, but the profits for investors were so impressive that people on Wall Street began to refer to Ward as “Futures Ferdinand.” Like the con men in Mark Twain’s and Charles Warner’s 1873 novel The Gilded Age (the title that gave this corrupt period its name), Ferd, who set up his own brokerage firm in 1879, wasn’t selling anything except dreams of the future, taking advantage of that “all-pervading speculativeness” that Twain thought was characteristic of the nation.

Will Ward’s roommate in the fashionable Bella apartment building was Ulysses S. Grant Jr., known as Buck. Ferd had money and success; Buck could bring in additional clients, including his own father, “the best-known American on earth.” In 1880, the firm of Grant & Ward was established. Soon, Ward claimed to have various government contracts on hand for shrewd investors. The former president’s considerable investments in Ward’s firm helped allay suspicion, and Ward induced Grant to sign a letter vouching for the safety of the investments.

Advertisement

Geoffrey Ward gives a vivid account of how his great-grandfather, whose “money machine…had constantly to be fueled by fresh cash from new investors,” seduced the gullible ex-president and his associates:

When Ferd learned that General Grant was having a dinner for a few business acquaintances, including Cyrus W. Field and William H. Vanderbilt, and that he was not invited, he determined to meet them anyway. Late that evening, just as the Grants and their guests were getting up from the table, the doorbell rang. It was Ferd in formal dress. Might he see the general, just for a moment? Grant appeared in the foyer. Ferd apologized for interrupting. He had stayed in the city to attend the opera, he said, and just wanted to step in to tell him that he’d “managed to make a little turn today—nothing to do with the firm—but just a little outside speculation and I put you in.”

The stock he had shrewdly picked had tripled in value by the close of business. Grant’s share of the profits was $3,000 (nearly $70,000 today), and Ferd thought, since he was in the neighborhood, he might as well just drop off the check. Grant was understandably delighted and insisted that his young partner join his guests in the parlor. There had been no actual investment, of course. The evening cost Ferd $3,000—but, he later said, he considered it “cheap at the price.”

Grant & Ward was, according to Geoffrey Ward, a wholly “imaginary business” and “fraudulent from the start.” There were no government contracts; there were only investors. Ferd Ward had hit upon the scheme later practiced by masters like Ponzi and Madoff: “He planned simply to keep the firm afloat and himself out of jail by pyramiding its funds; past investors were to be paid their supposed profits out of money freshly deposited by gullible new ones.” The profits, someone ought to have realized, were too good to be true. “No one quite understood it,” Geoffrey Ward notes, “but virtually everyone wanted to get in on it.” As Henry Clews, a Wall Street veteran, observed, “It is marvelous how the idea of large profits when presented to the mind in a plausible light, has the effect of stifling suspicion.”

3.

Ferdinand Ward’s expert handling of President Grant demonstrates his mastery of appearances. He was said to have a “hypnotic presence” and an “uncanny power” over his associates. Like the Wizard of Oz, he worked his magic from behind a heavy curtain in the office, giving the impression that he possessed insider knowledge. As his own profits accumulated, Ferd bought an ostentatious house in Brooklyn for his wife and their young son, Clarence, where he entertained on a grand scale:

Four Irish maids kept the oriental carpets clean and dusted the books and artworks. A French chef and his wife ran the kitchen. An Irish butler announced callers, saw that the wine cellar was fully stocked, and ensured that the staff maintained the lofty standards of service expected by residents of Brooklyn Heights. And in the Ward stable on Love Lane, just behind the house, where Ferd kept four horses, an Irish coachman made certain that the silver mountings on the harness were kept gleaming for the carriage rides Ferd and Ella took through Prospect Park and Green-Wood Cemetery every weekend.

Ferd’s prize was a lurid and very expensive painting of Christ Raising Jairus’s Daughter, which Van Gogh, who had seen a photograph of the picture, pronounced “particularly fine.” By 1880, as Geoffrey Ward notes, Ferd was “acting like a very rich man,” attracting additional dupes burdened with what his mother called, uneasily, the “disposition to be rich.”

In late 1883, Ferd choreographed what he himself considered the high point of his audacious career when he invited seven powerful financiers and politicians, including President Grant and the mayor of New York, for a three-day journey in a sumptuously appointed private railroad car to view the recently completed Kinzua Viaduct south of Bradford, Pennsylvania, the longest and tallest railroad bridge in the world. Ferd insisted that it was a pleasure trip and that business would not be discussed, a key provision, as Geoffrey Ward notes: “Should anyone riding in that car question another about what he knew or didn’t know about the shadowy contract business, everything might collapse.” The reader, forewarned by the dire subtitle of the book and ample foreshadowing of disaster, almost expects the train to plummet the three hundred feet into Kinzua Creek below.

For twelve years Ferdinand Ward succeeded in bamboozling investors before the inevitable collapse of his scheme in 1884. The enormous checks he wrote to demanding investors required a reliable bank and additional investors to back them. It was not a sustainable business model, of course. Ferd later admitted that his only hope was that he “might, through a more active stock market in the future, get even again.” The firm at one point owed at least $14.5 million to its creditors against less than $60,000 in assets. The Marine Bank, trafficking in illicit municipal bonds to shore up Ferd’s operation, was ruined in the process, triggering other bank failures. The bewildered ex-president showed up at Ferd’s office to learn the bad news. “When Grant left home that morning,” Geoffrey Ward writes, “he had believed himself a millionaire. When he got home in the evening he had $80 in his pocket. His wife had another $130. There was nothing else.”

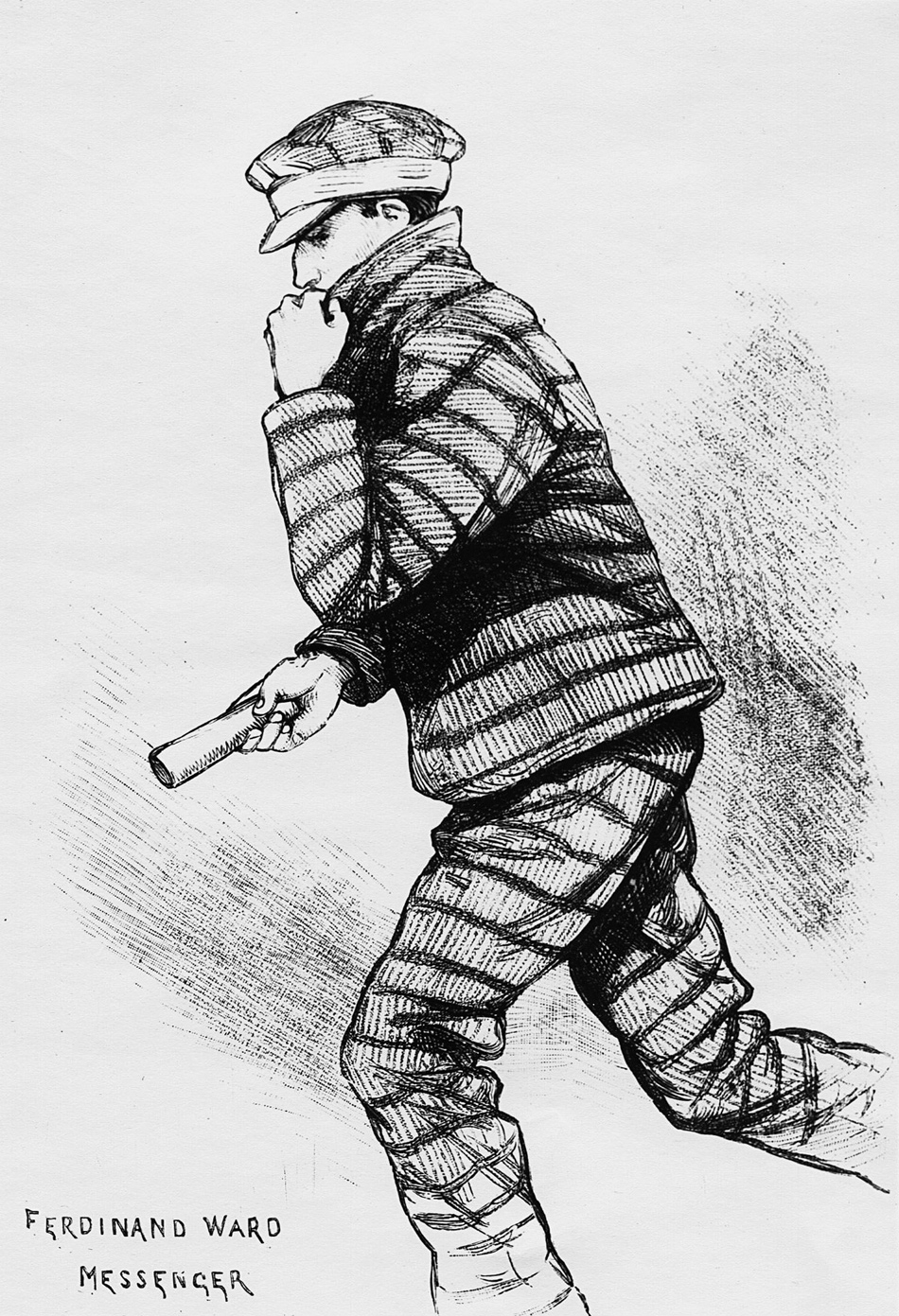

As details of Ferd’s fall became known, the press marveled at the “magnificent and audacious swindle” he had perpetrated. In the sensational trials that followed, comprehensively narrated by Geoffrey Ward, both Fish and Ferd were eventually convicted of fraud. Ferd spent six comfortable years in Sing Sing, where the prison doctor made moonshine and arrangements could be made for oriental rugs and easy chairs inside the cells and Thanksgiving dinners outside them. Ferd’s letters home, “eerily oblivious” of his wife’s feelings, consisted of urgent pleas for money; Ella finally offered him, sarcastically, the diamond from her wedding ring.

Faced with financial ruin, and diagnosed with cancer of the throat, Ulysses S. Grant decided to write his memoirs to support his wife. So, in an odd way, we have Ferd to thank for the most brilliant firsthand account of the winning of the Civil War, which will still be read when Ward and his book fade from memory. Profiting like Ferd from Grant’s famous name, Mark Twain outbid the Century magazine to publish it. When Twain visited Grant in early 1885, he was surprised to find that the great man’s anger at Ferd had waned. Twain, by contrast, was “inwardly boiling.”

I was scalping Ward, flaying him alive, breaking him on the wheel, pounding him to jelly, and cursing him with all the profanity known to the one language I am acquainted with, and helping it out in times of difficulty and distress with odds and ends of profanity drawn from the two other languages of which I have a limited knowledge.

4.

Geoffrey Ward adopts roughly the judgment that Mark Twain and other contemporaries held of Ferdinand Ward, that he was a detestable figure who cynically and selfishly brought down a great leader and bilked untold numbers of innocent people of their fortunes. But might there have been another way to tell the story? Here, one thinks of a third possible meaning of the title of Cather’s story “Paul’s Case,” namely, Paul’s case against the uniformity of the Gilded Age. Cather describes Paul’s neighborhood in such a way that his temporary escape from it feels like romantic rebellion:

It was a highly respectable street, where all the houses were exactly alike, and where business men of moderate means begot and reared large families of children, all of whom went to Sabbath-school and learned the shorter catechism, and were interested in arithmetic; all of whom were as exactly alike as their homes, and of a piece with the monotony in which they lived.

One can understand why Paul, whose life is “full of Sabbath-school picnics, petty economies, wholesome advice as to how to succeed in life, and the unescapable odors of cooking,” feels like a “prisoner set free” when he attends the theater.

Is there a kindred case to be made for Ferdinand Ward, who had to endure precisely such an upbringing before his escape to New York? The Gilded Age was in some ways so uniformly awful, so brimful of religious hypocrisy and political corruption—could we summon a little sympathy for the audacious scoundrel who brought it to its knees? Can we, perhaps a bit guiltily, admire the sheer bravura, the high-flying daring, of that railroad journey to the great bridge, where Ferd gambled everything on the wishful fantasies of grown men who should have known better, confident in the odds that they would keep their mouths shut as long as the too-good-to-be-true profits kept rolling in?

But any grudging sympathy one might be tempted to feel for Ferd is dashed, in the closing pages of the book, by his crass attempt to gain custody of his son in order to steal his inheritance. Ferd had ignored Clarence, who grew up in the care of Ferd’s brother-in-law, while he was in jail, sending him, at best, perfunctory notes; he couldn’t even remember the boy’s birthday. On his release, he realized that Clarence stood the best chance of providing him some money for starting over. First, he tried, without success, to play the adoring and concerned father, promising, incongruously, “we will have dogs and go fishing and swimming together and we will go down by the big ocean and dig up the sand and catch the crabs and hear the band play.” When sentimentality failed, he organized a crude scheme, also unsuccessful, to kidnap Clarence by force. A merciful court ruled for the in-laws.

Clarence Ward, who later became a respected art historian and director of the Allen Art Museum at Oberlin College, saw through his father’s schemes as so many others had not. As an undergraduate at Princeton, Clarence reluctantly agreed to meet with his father. By an odd coincidence, Mark Twain, “unmistakable in his ice cream suit,” happened to be in the dining hall. Ferd was “evidently frightened,” according to Geoffrey Ward, “that if Twain recognized him he would make good on his threat to avenge General Grant.”

Ferd had been caught, yet again, stealing from Geneseo citizens who had been foolish enough to allow him to do bookkeeping for them. He made his usual desperate plea for money. Clarence, as usual, refused to help him, adding for good measure, “I would be pleased if you would avoid the mockery of signing ‘your loving father’ in any further communications which you may have with me.”

The subject of this sometimes painful, often amusing, and strikingly well written “biography of a scoundrel” died of nephritis in 1925; Clarence, responsible to the last, made the funeral arrangements. Ferdinand Ward’s life might be summed up in his great-grandson Geoffrey Ward’s devastating words: “He never changed, never apologized, never explained.”

This Issue

December 6, 2012