In its normal setting on a wall of the Galleria Palatina in the Pitti Palace in Florence, The Vision of Ezekiel, partly by Raphael, partly by Giulio Romano, is one small painting in a multitude of paintings, most of them clamoring loudly for attention: Titian’s Bella and Raphael’s Donna Velata vie for the crown of voluptuous textures—velvets, silks, pearls, hair, living flesh. Nearby we see Raphael’s portrait of Tommaso Inghirami in wall-eyed rapture, the veins veritably pulsing beneath the surface of his skin, and the circular compactness that lends his Madonna of the Chair its intimacy.

Amid all this beautiful clamor any viewer can probably be forgiven for missing out on what The Vision of Ezekiel has to offer beneath its strange image of God descending in a cloud of apocalyptic monsters: an infinitesimal landscape with a tiny Ezekiel in the foreground, no larger than a silverfish, transfixed by a burst of heavenly light. But what a landscape! Its lazy river recedes back into endless depths between steep wooded hills. In the space of perhaps two inches by eight, the painting takes us on a dizzying flight straight up the Tiber valley to the green heart of Umbria, to the road that still leads from bustling cities like Florence and Perugia to Rome. It is a landscape as softened by the slow action of wind and water as Leonardo’s famous drawing of the upper Arno valley is stark and spiky, and it is a vision no less evocative of nature’s omnipresence, of perspectival depth and the artist’s commanding eye—but all contained within the lower margin of a painting that is largely taken up with a bizarre, and entirely unnatural, celestial vision.

When The Vision of Ezekiel hung all by itself on a wall of the Museo Nacional del Prado this summer (it is now to be seen in Paris), it finally commanded its rightful attention as a phenomenal work of art, its only neighbor a large tapestry showing the same arresting subject (see illustration on page 63). Woven on Raphael and Giulio Romano’s design in Flanders by the Fleming Pieter van Aelst, this hanging once decorated a canopy bed in the Vatican Palace for Pope Leo X. In its textile version, Ezekiel’s bizarre vision of God, cherubs, and apocalyptic beasts floats on clouds in the pure blue-gray air, free of all earthly ties, including Ezekiel himself. Van Aelst, a master of his craft, evokes the radically diverse textures of divine flesh, fur, bursts of light, and vaporous clouds by minutely adjusting the color of his woolen filaments; in its effect, the tapestry is both a monument and a miniature.

In the painted Vision of Ezekiel, however, the most captivating passage is the most incidental: this incomparable, and incomparably tiny, miniature landscape. All of Raphael’s preparatory drawings (and those of his assistants) concentrate exclusively on the airborne vision. The landscape seems to have been painted almost as a whimsy, but if so, it is the whimsy of a master. In its perfection this lovingly painted portrait of a place flies in the face of conventional art-historical wisdom, which says that the old masters who managed large workshops entrusted this kind of background detail to assistants and concentrated their own efforts on the faces and hands of the major figures.

Certainly artists’ contracts often stipulated that the masters themselves would deal with hands and faces, but it is clear from the exhibition “Late Raphael,” mounted jointly by the Museo Nacional del Prado and the Musée du Louvre, that Raphael painted whatever part of a picture he chose: foreground, background, top, bottom, middle, everything, and, often enough, nothing at all after supplying the basic design. The only way to know what part of a painting he really touched is to look at it, carefully, in every detail, which the Prado version of the Raphael exhibition made it very easy to do. There are paintings in which the background steals the show, on a small scale like the Tiber valley at the bottom of The Vision of Ezekiel, or on a monumental scale, like the landscape that basks in sunlight behind the cold gray rocks where a painfully young John the Baptist in the Wilderness sits for a moment, stretching out a long shapely leg.

In The Madonna of Divine Love, a peaceful Madonna and Child rest at twilight with the infant John the Baptist while Joseph stands guard well behind them, almost out of the way, keeping watch over his family from a place within the crumbling vaults of an ancient Roman ruin, plunged into sudden darkness as a winter twilight shifts abruptly to night. If you stand at the right vantage, the ruin suddenly snaps into three dimensions as only Raphael’s paintings can do. He worked this figure of Joseph, and this background, with his own hand, and it is impossible to stop looking at them.

Advertisement

When it comes down to it, why should a master painter be interested only in foregrounds, or figures? From the beginning of his career to the end, Raphael exploited every bit of the surface available to him. He also exploited the physical position of his viewers. To achieve its full effect, for example, his last painting, the Transfiguration, needs to be seen from a distance that can only be achieved under present circumstances by standing in the door to the neighboring room of the Vatican Picture Gallery. Then the upper half of this tall, two-tiered painting turns into a whirling vortex, a wind from heaven that presses down two of the three apostles who bear witness to the scene, and yanks the third one upward as it pulls Jesus, Moses, and Elijah up into its vacuum.

The spiral effect of the Transfiguration’s divine tornado is as forceful as an El Greco, and El Greco must have seen this painting, with its gyrating space and its silvery glow, on the high altar of the Roman church of San Pietro in Montorio; the future Pope Clement VII, who had ordered the painting for his bishopric in France, could not bear the prospect of never seeing it again. The version of the painting displayed in the Prado is a copy by Raphael’s two assistants, Giulio Romano and Gianfrancesco Penni, an excellent painting, but stripped of all the greenery that enlivens the original, stripped of the luxuriant silver yellows and serpentine greens that only Raphael could create by applying layer after layer of pigment, incorrigibly limited to two dimensions. But Raphael’s red chalk preparatory drawings for the original Transfiguration stand by his associates’ copy of his great panel painting as a reminder that his chief means of sparking their enthusiasm was the exuberant force of his talent.

Raphael and his contemporaries seldom worked in isolation. They learned their trade as artists by joining a workshop in late childhood, eventually becoming assistants, then collaborators, and at last, if they were sufficiently lucky and sufficiently talented, masters in their own right. The “Late Raphael” exhibition focuses special attention on two of Raphael’s closest associates, Giulio Romano and Gianfrancesco Penni, the most prominent members of a big, diversified workshop that may have included as many as fifty people at one time, from young boys to mature specialists who were dominant figures in their respective fields. Thus, under the general label of “Raphael,” Giulio and Penni carried out drawings and paintings, Marcantonio Raimondi concentrated on engravings, Giovanni da Udine on stucco, still lifes, grotesques, and animals, Lorenzetto on sculpture, Luigi de Pace on mosaic, Antonio da Sangallo on architecture, each of them at the highest level of quality.

At the heart of it all, Raphael bound all these different sensibilities into a coherent group that produced huge quantities of art in virtually every medium, at the same time maintaining a distinctive, consistent style across the board. Sustaining this level of quality and consistency was an achievement in itself, but the most interesting aspect of the workshop was its harmony: Raphael, in his brash, violent age, apparently deployed his forces with the utmost gentleness. As a leader and manager of fractious human beings under tremendous pressure, he provides a model for the ages.

The exhibition concentrates (as a traveling show must) on what its curators call “moveable art”: specifically, in this case, drawings, paintings, and tapestries. The works on display, together with the catalog, are enough to suggest some clues to Raphael’s success as the head of what qualified, to all intents and purposes, as at least a company and perhaps as an outright industry. One wonders what the artist learned about management from his most important private patron, the wily Tuscan banker Agostino Chigi, whose Rome-based business extended its tentacles from London to Constantinople; the relationship with Chigi was one of the most important in the course of his career.

Consciously or unconsciously, curators Tom Henry and Paul Joannides themselves embody one of the reasons for Raphael’s success as the master of a workshop; though they often disagree about the authorship or date of drawings, paintings, and details, they have a clear, shared idea of Raphael, his enterprise, and his art, fully aware that their shared vision depends to a significant extent on subjective judgments. Next to nothing is known about many of the drawings and paintings they have chosen for exhibition, and the only way to make a deeper sense of them is to compare them with the works that are better documented. Enjoying them is another matter; “Late Raphael,” dates and authorship aside, is an exultation of beautiful art.

Advertisement

Henry and Joannides have chosen to aim the catalog texts primarily at specialist art historians and curators, for whom it provides both a valuable record of changing ideas about Raphael, his working methods, and the works themselves and the opinions of two scholars who have looked long and hard at the full range of Raphael’s work—Joannides at the drawings, Henry at the paintings. Through their careful sifting of mountainous data (the bibliography on Raphael is notoriously vast) they provide fascinating new insights into this genteel master and the squadron that most contemporaries called his “boys,” both because many of them were so extremely young, and because Raphael treated them with such affection. In his 1550 biography of Gianfrancesco Penni, fellow artist Giorgio Vasari reported that Raphael “took [Gianfrancesco] into his home, and together with Giulio Romano always treated them as if they were his own sons.” Fatherly Raphael had lost his own father at the age of eleven, but must have preserved loving memories, at least to judge from his portrayals of Saint Joseph as the most gentle and attentive of fathers.

Like an observant father, Raphael seems to have continued to put his hand everywhere and anywhere in the workshop, even when his interests had spread outward to encompass archaeology and ancient literature and his commissions poured in from all sides. These hands-on interventions seem to have been as essential to establishing his artistic authority as his sense of organization, his creative energy, and his agreeable personality, for when he does apply his hand to a painting no one can come near him, not even Giulio Romano, his most gifted associate.

Perhaps because of his own supreme talent, Raphael was not a jealous master. Like Bramante, he was as competitive as any of the rivals he moved out of the way, but no anecdotes or documents record snide comments from either of these two gentlemen from Urbino about other artists’ work. Raphael’s rivals, on the other hand, could be vicious, none more so than Michelangelo Buonarroti and Sebastiano del Piombo, the Venetian painter who had come down to Rome with Agostino Chigi in 1511 and quickly lost the assignment of frescoing Chigi’s villa to Raphael.

Sebastiano apparently cherished a grudge as persistently as his irascible Florentine friend Michelangelo. A revealing example is the letter he wrote on July 2, 1518, to Michelangelo in Florence. He had just been to see the public display of Raphael’s Saint Michael and Holy Family of François I, two of the painter’s early experiments with sharp contrasts of light and shadow, both destined for the king of France. Both Sebastiano and Raphael were inspired to try chiaroscuro—stark contrasts—by the example of Leonardo da Vinci, who was living in Rome during this period and had the Mona Lisa and some of his drawings with him. Raphael’s chiaroscuro style was phenomenally influential, both in France and in Rome, and it is his example, rather than Leonardo’s, that probably convinced Caravaggio to adopt the chiaroscuro style that quickly made him famous. But Sebastiano, himself a master of moonlit effects, was unimpressed by Raphael’s results:

It pains my spirit [he wrote to Michelangelo] that you weren’t here to see two paintings that have been sent off to France by the Prince of the Synagogue…. I won’t say any more than that they look like figures that have been standing in smoke, or iron figures that glow, all bright and all black.

The epithet “Prince of the Synagogue” expresses more than simple anti-Semitism (though it expresses that too). Several of Raphael’s friends maintained close associations with Jews, including Agostino Chigi and Giles of Viterbo, the influential head of the Augustinian order and friend of Popes Julius II and Leo X, who hosted a rabbi in his house for several years. For the Augustinian mother church of Sant’Agostino, Raphael had painted an image of the prophet Isaiah in 1512, in which he flaunted the powerful muscles and brilliant pastels that Michelangelo had just brought into fashion on the Sistine Chapel ceiling (unveiled in 1512), all, however, done with his own incomparable delicacy of technique. Michelangelo, who had worked across the Sistine ceiling with huge sweeps of a very large brush, could not have missed either the reference to his own work or Raphael’s sublime dexterity in mimicking it.

Furthermore, Isaiah was the second time that Raphael had openly appropriated Michelangelo’s style: the first occasion was in 1511, when he inserted a sulky portrait of Michelangelo himself into his School of Athens, playing the part of the dour Greek philosopher Heraclitus. This tribute advertised not only the fact that Raphael could ape Michelangelo’s style, but also—more mortifying by far—that he had obtained a sneak preview of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Between 1508 and 1512, the space was supposedly off limits to nearly everyone, but Bramante and Raphael slipped in for a look in 1510, and the younger painter’s treatment of Michelangelo flaunts the escapade, as well as his own ability to suggest a velvety texture that no one else, least of all Michelangelo, could achieve in fresco. Raphael reserved the most velvety surface of all for Michelangelo’s suede dogskin boots, the one article of clothing the Florentine master truly loved. As for Isaiah, it is tempting to see him as a portrait of Giles of Viterbo’s rabbinical friend and Hebrew teacher Elias Levita, because the darkly handsome prophet carries a scroll written in perfectly legible Hebrew. The “Prince of the Synagogue” was the Prince of Painting in Rome, however hard Sebastiano tried to unseat him.

Henry and Joannides suggest that for several years, between about 1513 and 1517, Raphael’s drawings and paintings show a certain amount of confusion. His situation was certainly complicated enough to confuse anyone. Orphaned by the age of eleven, now in his early thirties (he was born in 1483), he must have realized by 1513 that he had become the dominant painter in papal Rome, at the very pinnacle of an energetic, competitive heap. Then he lost two of his greatest allies and father figures in short order. His first great patron, the fiery, driven Pope Julius II, died in 1513, followed by Raphael’s great-uncle and mentor, Donato Bramante, in 1514. Bramante, a close friend of the late pope, had been the architect who convinced Julius not simply to reinforce the thousand-year-old St. Peter’s basilica, but to replace it. In 1514, responsibility for this monumental project passed to Raphael. To supremacy in painting, he was suddenly compelled to add supremacy in architecture. He immediately set to work studying the Ten Books on Architecture of the ancient Roman writer Vitruvius, which meant learning Latin, archaeology, and construction technique while still managing the busiest workshop in Rome.

The way he chose to face his daunting position in these years provides another clue to Raphael’s success, and indeed his greatness: he placed implicit trust in his young associates, confident that they would work to his standards even before they were mature enough to do so reliably. Antonio da Sangallo was twenty-nine in 1513, but Giulio Romano was probably in his teens, and Gianfrancesco Penni either seventeen or twenty-five. Raphael inspired his precocious “boys” by his own example, and also by keeping a close watch on every stage of execution, as works of art passed from the stage of commission to sketch to model to completed object. He gave everyone on his team ample room to experiment, and, above all, he let them make mistakes. For the most part, the results were good enough to pass muster with patrons, and morale within the group was evidently high; Giovanni da Udine and Penni, especially, were never as productive alone as they were under Raphael’s direct guidance.

Gianfrancesco Penni was the son of a Florentine weaver, a painter whose work achieved something of the softness of Raphael’s textures for flesh, drapery, and landscape, but as time went on Raphael used the youth more and more as a personal assistant; his nickname, “Il Fattore,” means that he probably managed the master’s accounts. Raphael’s death in April 1520 was especially traumatic for the twenty-four-year-old Penni, who quickly revealed his limits as an artist in the absence of constant direction from his mentor. A faithful translator of Raphael’s complex compositions and an eager observer of Northern European artists like Dürer, he never quite found his own bearings in the eight years he spent on his own (he died in 1528 at the age of thirty-two).

He was not the only artist whose creative fire seemed to fizzle out after April 1520. Giovanni da Udine’s power of invention runs riot in the years around 1518. After close study of the surviving examples of ancient Roman decoration and a look at the instructions on pigments and stucco supplied by Vitruvius, he had succeeded in recreating the ancient Roman recipe for stucco in 1518 (the magic ingredient was powdered travertine). Soon Rome blossomed with his fanciful decorations, in stucco relief and in swift strokes of fresco. He peopled the Vatican Palace with grotesques, plants, animals, and mythological figures, in the loggia leading to the papal suite, in the suite of Pope Leo’s associate Cardinal Bibbiena, and the entrance loggia to Agostino Chigi’s villa (the Loggia of Cupid and Psyche).

After Raphael’s death, however, Giovanni’s creative energy begins to slow: his work in the Medici villa now known as Villa Madama is dazzling, but less clever than his work a few years earlier, and the loggia he painted just beneath the loggia of Leo X is equally limited for a painter who once seemed to notice, and exult in, every detail of art and nature.

For one member of the workshop, however, originality was less of a problem after Raphael’s passing than it had been before. Giulio Pippi, universally known as Giulio Romano, “the Roman,” was Raphael’s most talented, most privileged, and most unruly associate. He clearly loved Raphael, but his mentor’s death also freed him in many ways, including the liberation of his ribald sense of humor (proof, many Italians would say today, that Giulio was a real Romanaccio). It was only after Raphael died in 1520 that Giulio dared team up with the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi to produce a set of explicit erotic prints in vaguely classical settings known as I modi (“ways to do it”). Coupled with sonnets penned by another of Agostino Chigi’s protégés, the Tuscan writer Pietro Aretino, I modi became an underground hit and a public scandal.*

To be sure, Raphael had given the boys fairly free rein when it came to decorating the entrance hall for Chigi’s suburban villa, where Giovanni da Udine produced some of the world’s most suggestive fruits and vegetables, including an obscene coupling of gourd and fig right above the entrance to Chigi’s study. Just below the randy gourd, Gianfrancesco Penni supplied a flying Mercury who looks more stark naked than heroically nude, and throughout the rest of the room Giulio provided a bevy of buxom goddesses who wear no more than elaborate hairdos, no two of them alike. Chigi and Aretino, both on hand in 1518, no doubt provided appropriate commentary, but it was private, not public.

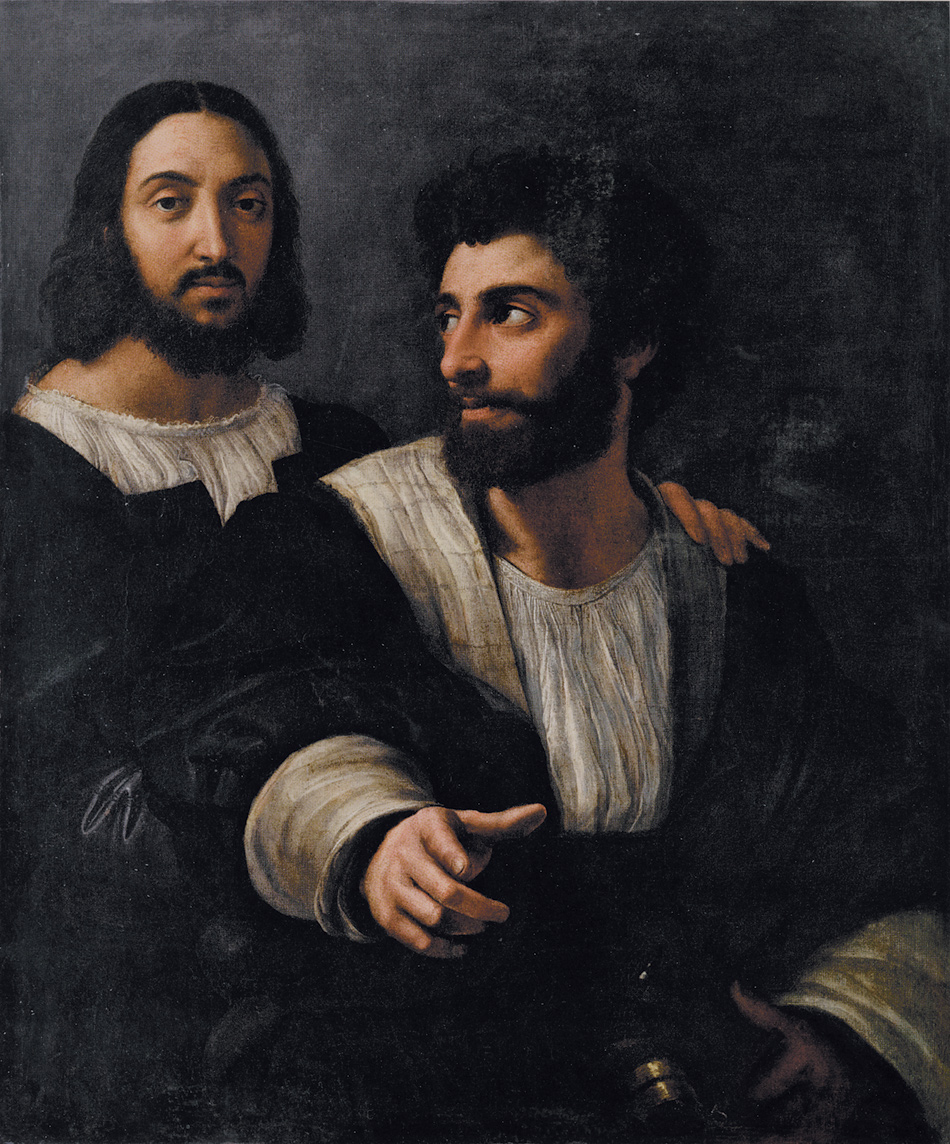

I modi, on the other hand, were published, distributed to the masses. Marcantonio was eventually brought to trial for copyright violation, and Giulio moved on to Mantua, where the reigning marquess, Federico Gonzaga, proved a kindred soul. Henry and Joannides argue that the famous double portrait of Raphael and a younger friend shows Raphael and Giulio Romano, and the identification has much to recommend it, although there are some significant differences between the features of the young man and Titian’s later portrait of a middle-aged, successful Giulio (unless the older Giulio had begun plucking his eyebrows and Titian ignored the shape of his ears). Infrared reflectography reveals that the two figures were once posed almost side by side, but Raphael eventually thought better of it and moved his own figure higher, so that he could clap his friend paternally on the shoulder—another reason to suppose that the friend might be restless, ambitious Giulio.

The younger man’s sword and the sober dress of the pair indicate that they are two gentlemen; in effect, Raphael is passing his hard-earned and still novel status as gentleman artist on to his protégé. Giulio knew how to accept the lesson; he was the one member of “the boys” who came from well-born parents, and in Mantua he became exactly the kind of gentleman artist this painted letter of recommendation assumes he will become. Men of consequence normally dressed soberly in early-sixteenth-century Rome, favoring dark hues like the black the sitters wear in most of Raphael’s “friendship” portraits. (Hence middle-aged Leonardo made quite an impression in his pink cloaks and pink tights.) The young Florentine banker Bindo Altoviti, on the other hand, wears a mantle of deep blue, the better to bring out his limpid blue-gray eyes, bee-stung lips, and luxuriant blond hair (soon to fall victim to male-pattern baldness, just like the young Giulio Romano’s raven curls).

We can only be grateful to Bindo and Raphael for choosing to privilege beauty over conventional sobriety. And it is hard to feel entirely sober in the presence of Raphael’s portrait of his friend Baldassare Castiglione, clad in muted gray and black, but in what sensuous textures, and with what scintillating points of red and blue adding life to the fabric. This was a painter who saw beauty in every part of his friends, from their character to their choice of clothing. It is a pity that no portraits of Agostino Chigi survive (apparently they existed once).

Raphael pays homage to friendship of another sort in his Donna Velata, both the portrait of a beautiful sleeve and a beautiful woman, every stroke of it from his own hand, from the tendril of curling hair that barely brushes her face to the provocative finger that plays with the fastening of her bodice. The Donna Velata hangs under normal circumstances in the same room in Florence as Titian (in the Galleria Palatina), with Rubens just down the hall, and they make perfect company: the three men whose love affair with women and oil paint reached the ultimate pitch of jubilation.

Raphael’s assistants could never quite reach this level, though Giulio sometimes came close. Nonetheless, the gentle master consistently brought out the very best in the members of his workshop, as their creations with him and without him reveal consistently and unequivocally. In his own day, only Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Titian could rival his infectious exuberance and impeccable control. But neither Leonardo, nor Michelangelo, nor Titian could have produced the little vignette of the upper Tiber valley beneath the feet of Ezekiel’s apparition. The bird’s-eye view and the deeply receding space may well owe an essential debt to Leonardo (viewers at the Louvre can compare The Vision of Ezekiel with the valley behind the Mona Lisa), but the sun-soaked colors belong to Raphael alone.

The exhibition curators identify the painter of this entire panel as Giulio Romano, working from a drawing by Raphael. The surviving preparatory drawings, however, show only the apparition itself, a white-haired man perched somewhat awkwardly among the clouds on a quartet of flying beasts. The exquisite little landscape must have been added freehand. Giorgio Vasari, writing in 1550, assumed that the landscape was by Raphael. It looks that way to this writer, too.

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right