The first novel of South African writer Zakes Mda, Ways of Dying (1995), told the story of Toloki, a down-at-the-heels loner who witnesses the mindless violence that convulses a black community in the final days of apartheid. He becomes a professional mourner and wanders from funeral to funeral, varying the mourning ritual he performs to suit each occasion. For instance, he knows never to sit inside the house for the meal after the township funerals of the “better-off people”—he might not be welcome—but to line up and eat standing from a paper or plastic plate. He must also not mix with the “rabble,” who will be fed outside from communal basins.

He eventually reunites with an old sweetheart from his home village and after the death of her son becomes more seriously involved with the ongoing battles of township life over the post-apartheid leadership. The novel’s most distinctive feature is the skillful use of flashback, particularly in the childhood scenes that intersperse Toloki’s journey toward a more superior milieu. This gives the novel a sophistication of movement that belies the somewhat folksy and, in the end, perhaps overly optimistic trajectory of the story, into a conclusion in which a New Year’s Eve celebration under a moonlit glow seems to herald the end of thieving and brutality:

The smell of burning rubber fills the air. But this time it is not mingled with the sickly stench of roasting human flesh. Just pure wholesome rubber.

Mda’s best-known novel, The Heart of Redness (2000), also made use of a bold structural device. One story takes place in the middle of the nineteenth century, in the small village of Qolorha-by-Sea in the Eastern Cape, where a teenage girl named Nongqawuse has a vision and then instructs the villagers to slaughter all their cattle as a sacrifice to the gods. She assures them that the ancestors will then rise from their graves and defeat the British. The folly of following this spiritual path results in the defeat of the amaXhosa people, and the consequences of this act continue to the present day.

A parallel modern-day narrative concerns Camagu, a man in his forties, who, armed with a doctorate, returns after many years in the United States to South Africa, where new, corrupt elites stand in his way and he fails to find a job. Thoroughly disillusioned, he decides to return to America, but on the eve of his departure he meets a beautiful girl and follows her to Qolorha-by-Sea. There he becomes involved in the disputes in this still-divided village between those who are keen to embrace the modernized world of casinos and “development” and those who remain true to the traditional values visible in Nongqawuse’s story.

Mda maintains a tension between a haunted past and an impatient, potentially violent present, and the novel’s restless movement allows him to suggest a much more complex analysis of history and place than in Ways of Dying. Mda has published four more novels in the past ten years, and he continues to experiment with form. At times the resulting fusion of lyricism, fancifulness, social realism, and increasingly overt political commentary proves unwieldy, as in The Whale Caller (2005), a witty love story exploring the “eternal triangle: man, woman and whale,” which eventually collapses into an almost apocalyptic ending: children stone a woman to death and a whale is blown up, causing blubber to rain down from the sky. The destruction of the idyllic peace of The Whale Caller by acts of shocking violence reminds us that South Africa’s emerging society has a long way to travel before it can escape the historical violence that shaped its past. Mda’s fiction reminds us of this on many levels; an unflinching willingness to criticize the imagined utopia of the new South Africa, coupled with his formal inventiveness, characterizes the best of his fictional achievement.

Born in 1948, Zakes Mda belongs to a g eneration of South African writers—including Damon Galgut, Ivan Vladislavic, and Achmat Dangor—who have achieved international recognition in the decades since apartheid was dismantled. He was born in South Africa, but as a teenager was sent to live with his father in Lesotho, where he continued his schooling before returning to South Africa as an adult. “I have resisted the centre,” states Mda, “and have always drifted towards the periphery of things.” For the past decade he has been a professor at Ohio University, living for most of the year in the United States.

His new memoir, Sometimes There Is a Void, brings to light how similar Mda is to his often severe and determined late father, a man he clearly admires and with whom he wishes he had spent more time. A.P. Mda taught in Lesotho schools, then became a lawyer, and was a founding member of the African National Congress Youth League and a colleague of Nelson Mandela (who in 1947 handled a court case on his behalf). When his children got into trouble, he would remind them that “Africa cannot afford to have people who do such things.” A staunch and committed African nationalist, Mda was eventually forced into exile in Lesotho where he continued to oppose the apartheid regime while building a successful legal practice, often representing his poorer clients for no payment. His wife, Zakes Mda’s mother, was a registered nurse and midwife, and she had a deep influence on him. Her son’s portrait of this “beautiful and gentle soul” is filled with genuine warmth and respect. Clearly they were remarkable parents. They raised four sons (of whom Zakes was the eldest) and one daughter through extremely difficult times, all the while attempting to instill in them the virtues of discipline, respect, and hard work.

Advertisement

Young Zakes is a free-spirited child, which means that he occasionally lets down his parents during a “rampant and unruly adolescence.” He cheats on school exams, drinks excessively, loiters in shebeens, hustles tourists, and, after an early marriage in which he admits to being “an absent father and an irresponsible husband,” effectively abandons his wife and young children. He spends some years teaching in a primary school, working in a bank, and then setting up his own advertising and promotion business, eventually deciding to follow his father by making his career in the law.

While still in high school, however, Mda had begun to write plays, and balancing the demands of the legal profession with his artistic interests proved difficult. After the 1976 Soweto uprising his friendship with newly arrived South African exiles in Lesotho rekindled his interest in poetry and drama. Mda entered a play, We Shall Sing for the Fatherland, in a South African competition and unexpectedly won the runner-up prize. The play looked forward to the themes of his fiction, examining the lives of the veterans of the liberation struggle now marginalized in the new society they helped to create. Encouraged by this success, he abandoned the law without telling his father.

Eventually Mda’s plays began to be performed, and then published. Now in his early thirties, he decided to leave Lesotho, and his estranged wife and three children, and travel to America to pursue an MFA in playwriting. He secured a tuition waver from Ohio University, and borrowed the one-way airfare from a friend. Arriving without resources in Athens, Ohio, he remembered that Jane Fonda (whom he had encountered at an official dinner in Lesotho) had encouraged him to get in touch should he ever travel to the United States. He wrote to her, and Fonda put him on her payroll as a “script consultant,” which enabled him to move into better quarters.

Mda completed two master’s degrees and returned to Lesotho to a large celebratory party that his father had arranged for his formerly wayward son. Dressed in full academic regalia, and standing on a stage under the watchful gaze of his proud father, Mda seemed to have finally turned his life around. He received a Ph.D. in drama at the University of Cape Town and accepted a job as controller of programmes at Radio Lesotho. The appointment came with a car and driver, and a high salary, but Mda had trouble keeping up with the official demand that he be little more than a “propagandist.”

I felt dirty and had to take a bath as soon as I got home to the luxury flat that the government was renting for me near Victoria Hotel.

After less than a year he gave up his government sinecure and started teaching at the National University of Lesotho, determined to cut back on the drinking that had interfered with his efforts to establish himself. He was soon promoted to senior lecturer and head of the English department and seriously applied himself to the business of being a writer.

Mda frames this life story within a present-day journey he is making in his “Mercedes Benz sedan” to a beekeeping collective in the Eastern Cape that he helps support. He is undertaking this journey with his third wife, Gugu, and along the way he makes detours and stops to visit the old houses, hotels, schools, and townships of his past; his travels evoke the memories that make up the book. Stopping to visit one old haunt, for example, Mda discovers that

Bensonvale College is no longer there. Only the ruins. I almost weep. The whole college that used to be vibrant with students walking up and down the paved paths is gone. Ivy still covers those walls that have been defiant enough to remain standing. I stop the car on the edge of an open field and get out of the car. Gugu follows. I can hear the voices. At first they are soft, but as if carried by a gust of wind towards me they gather volume and become so loud that I lift my arms in supplication. They are the voices of the beautiful men and women of the Today’s Choir. And indeed the choir materialises in the field—women in black skirts and white blouses, men in black pants, white shirts, black jackets and black ties. My father in his black suit standing in front of them. Waving his arms, conducting the choir with gusto.

The landscape continues to divulge its secrets. We learn that Mda was sexually abused as a young boy by an older woman, and struggled subsequently with sexual performance; now however he has become “quite a stallion” and he enthusiastically recounts his liaisons. We also learn of his concern that he might have been partly culpable for the death of a beloved schoolfriend who fell ill during a night when it was Mda’s responsibility, as deputy head prefect, to answer his calls for help. He shares his feelings of shame at having struck a girlfriend.

Advertisement

Clearly some of these revelations shed light on his fiction. The world of “unbridled promiscuity” he recalls reminds us that in The Heart of Redness Camugu is prepared to act upon his desires for a young woman even if it leads him away from a return to America and maroons him in an uninspiring small African coastal town. We can clearly see the same carelessly romantic impulses informing the early years of Mda’s life.

Predictably, as Mda’s writing career gathers momentum, the memoir’s itinerant form becomes increasingly unwieldy and questionably relevant. The author includes five pages (which is not the whole text) of a letter he writes to Nelson Mandela complaining about the current situation in South Africa. Mandela, we learn, “did not write back. No. He phoned.” A subsequent lunch with two cabinet ministers (a third fails to show) led nowhere. One begins to feel like a captive audience:

Perhaps the meeting was just a way of shutting me up. Well, I shouldn’t complain; in other countries they shut you up by imprisoning you if you’re lucky, or by feeding you to the crocodiles instead of feeding you sumptuous Indian cuisine of vegetarian biryani, assorted pickles and chutney, served with garlic naan.

A 1997 junket to Chile seems included only to mention the names of his fellow invitees, “South African writers Nadine Gordimer, Wally Serote and Andre Brink; Chilean writers Ariel Dorfman and Antonio Skármeta; and Australian writers Peter Carey, Helen Garner and Roberta Sykes.” (We have already learned that Mda has his own biographer, “a sweet elderly lady from Cape Town” who has “become close not only to my immediate family but to my distant relatives as well.”)

The reader may ask if once a writer has closed the circle on his or her life that led to his writing, might he then let his novels and plays deal with the rest of the journey, or else pass the task of rummaging in his later life to literary biographers? The last quarter of Mda’s memoir is dedicated to his difficult marriage, protracted custody battle, and subsequent divorce from his second wife, Adele. He quotes her e-mails, her friends, her lawyer, and his own e-mails to her as he recreates the breakdown of his relationship, and though he tries to be fair to Adele, he cannot contain his self-justifying frustration and contempt. By now we feel we are eavesdropping on very private matters.

This is not to say that Mda should not have written a memoir at all, but somewhere lurking within his book’s 550 pages there is undoubtedly a shorter, more thoughtful book, one that would better illuminate both the man and his writing. Beyond these tales of “becoming,” writers may draw on their own lives when they suffer a loss that causes them to take stock of their lives: one thinks of Philip Roth’s touching kaddish to his father in Patrimony or recent books by Joyce Carol Oates and Joan Didion. In such cases, a strong command of the experience of loss clarifies the unwieldy matter of life.

In the end, Mda’s memoir cannot be viewed as a fully coherent narrative of how he became a writer, for once he has achieved success the story plows on relentlessly as he begins to rail against the South African state, the Market Theatre, his publishers, and his second wife, and to litter the text with lists of achievements and the names of famous people. Nor can it be seen as a narrative of loss, for we never come to know the two most poignant characters, his late father and mother, who bring a quiet dignity to the story. The great historic upheaval that forms its backdrop, and the significant body of work that creates its interest, become obscured by the excessive details of an often unexamined life.

This Issue

January 10, 2013

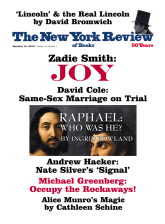

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right